Vocal Philologies: Written on Skin and the Troubadours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

Written on Skin

WRITTEN ON SKIN 10. NOVEMBER 2018 ELBPHILHARMONIE GROSSER SAAL Sa, 10. November 2018 | 20 Uhr | Elbphilharmonie Großer Saal Elbphilharmonie für Kenner 1 | 2. Konzert 19 Uhr | Einführungsgespräch mit Martin Crimp und Johannes Blum im Großen Saal MULTIVERSUM GEORGE BENJAMIN MAHLER CHAMBER ORCHESTRA GEORGIA JARMAN AGNÈS EVAN HUGHES PROTECTOR BEJUN MEHTA ANGEL 1 / THE BOY VICTORIA SIMMONDS ANGEL 2 / MARIE ROBERT MURRAY ANGEL 3 / JOHN MARTIN CRIMP TEXT BENJAMIN DAVIS REGIE DIRIGENT SIR GEORGE BENJAMIN George Benjamin Written on Skin (2012) Semiszenische Aufführung in englischer Sprache Keine Pause / Ende gegen 21:45 Uhr Gefördert durch die 7797 BMW 8er HH Elbphil 148x210 Programmheft 2018.indd 1 08.08.18 10:45 WILLKOMMEN Nicht vielen Neukompositionen ist es vergönnt, sogleich Teil des Kanons zu werden. George L U X Benjamin gelang das Kunststück mit seiner 2012 uraufgeführten Oper »Written on Skin«, die seit her gut hundertmal in aller Welt gespielt wurde. AETERNA Darin geht es um eine unglückliche Affäre, den EIN MUSIKFEST FÜR DIE SEELE Weg einer Frau zu sich selbst und ein »auf Haut geschriebenes« Buch, das seinem Schöpfer am DIE TANZENDEN DERWISCHE AUS DAMASKUS, Ende den Tod bringt. Zum Auftakt von George NDR ELBPHILHARMONIE ORCHESTER, INGO METZMACHER, ENSEMBLE RESONANZ, PEKKA KUUSISTO, HOURIA AÏCHI, Benjamins aktueller, groß angelegter Residenz IVETA APKALNA, ANNA LUCIA RICHTER, GEORG NIGL, an der Elbphilharmonie kommen neben dem DUO NAQSH, ROKIA TRAORÉ, CRAIG TABORN dirigierenden Komponisten selbst viele Mitwir kende der Uraufführung nach Hamburg, darun ter der Countertenor Bejun Mehta und das ful 3. 27. FEBRUAR 2019 ELBPHILHARMONIE, LAEISZHALLE, minante Mahler Chamber Orchestra. ST. KATHARINEN, PLANETARIUM, ST. -

Vocal Philologies: Written on Skin and the Troubadours

Vocal Philologies: Written on Skin and the Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/33/3-4/207/4801221 by University of California, Irvine user on 14 September 2020 Troubadours emma dillon king’s college london Parchment or slate were precious materials to the medieval scholar—or com- poser—and they were used repeatedly for successive sketching. Today, many cen- turies later, surviving manuscripts appear chaotic, with a surface complexity almost resembling organic growth, although their straight lines reveal they are man-made. In deciphering these mysterious objects one can unravel the sequence of layers and trace back to the initial text. —George Benjamin, program note to Palimpsests for Orchestra (1998À2002)1 Protector: What is it that you are looking at? Boy: Nothing, says the Boy, thumbing the knife. Protector: Thinking about? Boy: I’m thinking that when this wood and this light are cut through by eight lanes of poured concrete, I’m thinking that the two of us and everyone we love will have been dead for a thousand years. Protector: The future’s easy: tell me about now. —George Benjamin, Written on Skin, text for music by Martin Crimp (Part II, scene 9)2 Parchment is an unexpected vocal source to bring to a special issue on the voice in contemporary opera studies. In a field such as medieval studies, my more familiar scholarly habitat, parchment is the common currency of the voice: the ultimate proxy for vocal acts that are long since gone. Voice in the context of parchment is synonymous with the philological activity required to decipher information about song-acts as they were transmitted, reworked, and sometimes corrupted in the me- dium of ink, notation, and skin. -

Hannigan Ascending BACH ST

PRICELESS! Vol 20 No 5 CONCERT LISTINGS | FEBRUARY 1 - MARCH 7 2015 Hannigan Ascending BACH ST. JOHN PASSION BACH ST. JOHN PASSION BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND! HOUSE OF DREAMS DIRECTED BY IVARS TAURINS Mar 19-22, 2015 Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre, Jeanne Lamon Hall DIRECTED BY Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra JEANNE LAMON and Chamber Choir CONCEIVED, SCRIPTED, AND Julia Doyle, soprano PROGRAMMED BY Daniel Taylor, countertenor ALISON MACKAY Charles Daniels, tenor Peter Harvey, baritone Feb 11-15, 2015 Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre, Jeanne Lamon Hall “A testament to his faith, Bach’s Passions speak to us of the Journey to the meeting places of baroque art and music fea- turing music by , , , and more. greater human experience through music Bach Handel Vivaldi of powerful drama and profound beauty.” Don’t miss this stunning multimedia — IVARS TAURINS event before it goes on tour to Australia! A CO-PRODUCTION WITH Stage Direction by Marshall Pynkoski Production Design by Glenn Davidson Projection Design by Raha Javanfar 416.964.6337 Narrated by Blair Williams tafelmusik.org SEASON PRESENTING SPONSOR Baroque Orchestra and Chamber Choir SEASON PRESENTING SPONSOR The TSO and festival curator George Benjamin join forces with Canadian soprano Barbara Hannigan for new sounds, cutting-edge drama, and 7 premières! A Mind of Winter SAT, FEB 28 AT 8pm Peter Oundjian, conductor and host George Benjamin, conductor Barbara Hannigan, soprano Jonathan Crow, violin Dai Fujikura: Tocar y Luchar (CANADIAN PREMIÈRE) George Benjamin: A Mind of Winter (CANADIAN PREMIÈRE) Vivian Fung: Violin Concerto No. 2 “Of Snow and Ice”(WORLD PREMIÈRE/TSO COMMISSION) Dutilleux: Métaboles Pre-concert Performance, Intermission Chat, and Post-concert Party in the Lobby. -

T H E P Ro G

08-11 Skin_GP2 copy 7/30/15 2:46 PM Page 1 Tuesday Evening, August 11, 2015 at 7:30 Thursday Evening, August 13, 2015 at 7:30 m Saturday Afternoon, August 15, 2015 at 3:00 a r g o Written on Skin (U.S. stage premiere) r P Opera in Three Parts e Music by George Benjamin h Text by Martin Crimp T This performance is approximately one hour and 40 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. Presented in collaboration with the New York Philharmonic as part of the Lincoln Center–New York Philharmonic Opera Initiative (Program continued) Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. The Mostly Mozart Festival presentation of Written on Skin is made possible in part by major support from Sarah Billinghurst Solomon and Howard Solomon. These performances are made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Cen ter. David H. Koch Theater 08-11 Skin_GP2 copy 7/30/15 2:46 PM Page 2 Mostly Mozart Festival The Mostly Mozart Festival is made possible by Sarah Billinghurst Solomon and Howard Solomon, Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser, Chris and Bruce Crawford, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc., Charles E. Culpeper Foundation, S.H. and Helen R. Scheuer Family Foundation, and Friends of Mostly Mozart. Public support is provided by the New York State Council on the Arts. Artist Catering provided by Zabar’s and zabars.com MetLife is the National Sponsor of Lincoln Center United Airlines is a Supporter of Lincoln Center WABC-TV is a Supporter of Lincoln Center “Summer at Lincoln Center” is supported by Diet Pepsi Time Out New York is a Media Partner of Summer at Lincoln Center Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, U.S. -

NI5976 Book 1 Note

George Benjamin Born in 1960, George Benjamin began composing at the age of seven. In 1976 he entered the Paris Conservatoire to study with Messiaen, after which he worked with Alexander Goehr at George Benjamin King's College, Cambridge. When he was only 20 years old, Ringed by the Flat Horizon was played at the BBC Proms by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Mark Elder. The London & Sinfonietta and Simon Rattle premiered At First Light two years later. Antara was commissioned Martin Crimp for the 10th anniversary of the Pompidou Centre in 1987 and Three Inventions was written for the 75th Salzburg Festival in 1995. The London Symphony Orchestra under Pierre Boulez premiered Palimpsests in 2002 to mark the opening of ‘By George’, a season-long portrait which included the first performance of Shadowlines by Pierre-Laurent Aimard. More recent celebrations of Benjamin’s work have taken place at the Southbank Centre in 2012 (as part of the UK’s Cultural Olympiad), at the Barbican in 2016 and at the Wigmore Hall in 2019. The last decade has also seen multi-concert retrospectives in San Francisco, Frankfurt, Turin, Milan, Aldeburgh, Toronto, Dortmund, New York and at the 2018 Holland Festival. Benjamin’s first operatic work Into the Little Hill, written with playwright Martin Crimp, was commissioned in 2006 by the Festival d'Automne in Paris. Their second collaboration, Written on Skin, premiered at the Aix-en-Provence festival in July 2012, has since been scheduled by over 20 international opera houses, winning as many international awards. Lessons in Love and Violence, a third collaboration with Martin Crimp, premiered at the Royal Opera House in 2018; both works were filmed by BBC television, and a related ’Imagine’ profile on Benjamin was broadcast on BBC1 in October 2018. -

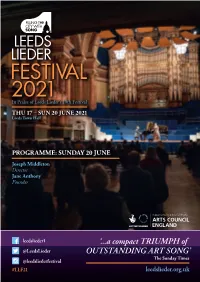

Sunday 20Th June

PROGRAMME: SUNDAY 20 JUNE Joseph Middleton Director Jane Anthony Founder leedslieder1 @LeedsLieder @leedsliederfestival #LLF21 Welcome to The Leeds Lieder 2021 Festival Ten Festivals and a Pandemic! In 2004 a group of passionate, visionary song enthusiasts began programming recitals in Leeds and this venture has steadily grown to become the jam-packed season we now enjoy. With multiple artistic partners and thousands of individuals attending our events every year, Leeds Lieder is a true cultural success story. 2020 Ameling Elly was certainly a year of reacting nimbly and working in new paradigms. Middleton Joseph We turned Leeds Lieder into its own broadcaster and went digital. It has Director, Leeds Lieder Director, been extremely rewarding to connect with audiences all over the world Leeds Lieder President, throughout the past 12 months, and to support artists both internationally known and just starting out. The support of our Friends and the generosity shown by our audiences has meant that we have been able to continue our award-winning education programmes online, commission new works and provide valuable training for young artists. In 2021 we have invited more musicians than ever before to appear in our Festival and for the first time we look forward to being hosted by Leeds Town Hall. The art of the A message from Elly Ameling, song recital continues to be relevant and flourish in Yorkshire. Hon. President of Leeds Lieder As the finest Festival of art song in the North, we continue to provide a platform for international stars to rub shoulders with the next generation As long as I have been in joyful contact with Leeds Lieder, from 2005 until of emerging musicians. -

© D Y La N C O Lla Rd

© Dylan Collard BRIAN FERNEYHOUGH (*1943) 1 Terrain (1992) 14:12 for solo violin, flute/piccolo, clarinet/bass, oboe/cor anglais, bassoon, trumpet, trombone, horn, contrabass 2 no time (at all) (2004) 7:25 for guitar duo 3 La Chute d’Icare (Petite sérénade de la disparition) (1988) 9:37 for solo clarinet, piccolo/alto/bass flute, oboe/cor anglais, percussion, piano, violin, violoncello, contrabass 4 Incipits (1996) 11:08 for solo viola, obbligato percussion, piccolo/bass flute, Eb clarinet/bass, violins (2), violoncello, contrabass 5 Les Froissements d’Ailes de Gabriel (2003) 17:47 for solo guitar, flute/piccolo/bass flute, oboe/cor anglais, clarinet/clarinet in Eb, bass clarinet/ contrabass clarinet, horn, trumpet/soprano trombone, trombone/bass trumpet, piano, guitar, harp, percussion, violin, violoncello TT: 60:09 1 Graeme Jennings violin 2 Geoffrey Morris guitar • Ken Murray guitar 3 Carl Rosman clarinet 4 Erkki Veltheim viola 5 Geoffrey Morris guitar 1 - 5 ELISION Ensemble • 1 , 4 , 5 Franck Ollu conductor • 3 Jean Deroyer conductor 2 ELISION Ensemble Paula Rae Piccolo/ Alto/ Bass Flutes Alexandre Oguey Oboe/cor anglais (1) Peter Veale Oboe/cor anglais (3, 5) Richard Haynes Bb/Eb/BassClarinets (1, 5) Anthony Burr Eb/Bass Clarinet (4) Brian Catchlove Bass/Contrabass Clarinet Noriko Shimada Bassoon Ysolt Clark Horn Tristram Williams trumpet/soprano trombone Benjamin Marks Trombone/bass trumpet Peter Neville Percussion Geoffrey Morris Guitar (2, 5) Ken Murray Guitar (2) Marshall McGuire Harp Marilyn Nonken Piano Graeme Jennings Violin (1, 3) Susanne PIerotti Violin (4, 5) Elizabeth Sellars Violin (4) Erkki Veltheim Viola Rosanne Hunt Violoncello (4, 5) Andrew Shetliffe Violoncello (3) Joan Wright Contrabass 3 Concerto, que me veux-tu? riere ist das Streichquartett das deutlichste Bei- Richard Toop spiel für letztere Form der Auseinandersetzung. -

George Benjamin (B.1960) Dream of the Song (2015)

George Benjamin (b.1960) Dream of the Song (2015) George William John Benjamin was born on January 31, 1960, in London, and lives there. “Dream of the Song” was a co-commission of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, and Festival d’Automne. The world premiere was given September 25, 2015, by countertenor Bejun Mehta with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and Netherlands Chamber Choir under the composer’s direction. The BSO’s part in the commission was to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Tanglewood Music Center. The American premiere took place at Tanglewood in July 2016, with Stefan Asbury conducting the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra, countertenor Daniel Moody, and the Lorelei Ensemble in Seiji Ozawa Hall. The score of “Dream of the Song” calls for countertenor solo, an ensemble of eight solo voices, two oboes, four horns, percussion (two players: glockenspiel, two vibraphones, two gongs, two pairs of cymbals), two harps, and strings. Duration is about fifteen minutes. Vocal music has dominated George Benjamin’s recent catalog: his opera Written on Skin, on a text by playwright Martin Crimp, has been acclaimed since its 2012 premiere as among the best operas in a generation, a masterpiece of the new millennium. This succeeded the composer’s “lyric tale” Into the Little Hill, also in collaboration with Crimp, a smaller-scale but also highly praised dramatic work. In their accumulations of scenes into works of forty and ninety minutes, respectively, Into the Little Hill and Written on Skin represented vast expansions of his compositional canvas. This newfound breadth and the concentration on the human voice—which are, naturally, closely related phenomena—continue in his latest work, Dream of the Song, an orchestral song cycle for countertenor that is his biggest non-stage work, arguably, since 1987’s Antara. -

Dossier Pédagogique Into the Little Hill

Into the Little Hill Opéra de George Benjamin 6-7 novembre 2019 Livret Martin Crimp Direction musicale Alphonse Cemin Mise en scène Jacques Osinski Ensemble Carabanchel Me 6 novembre à 20h Je 7 novembre à 14h30 Contact p. 3 Préparer votre venue Service des relations avec les publics p. 4 Claire Cantuel / Marion Dugon Résumé Delphine Feillée / Léa Siebenbour 03 62 72 19 13 p. 5 [email protected] Les personnages p. 7 OPÉRA DE LILLE George Benjamin 2, rue des Bons-Enfants BP 133 p. 8 59001 Lille cedex Le guide d’écoute Dossier réalisé avec la collaboration p. 14 Le projet de mise en scène d’Emmanuelle Lempereur, enseignante missionnée à l’Opéra de Lille. p. 16 Septembre 2019. Repères biographiques : chef d’orchestre et metteur en scène p. 17 En classe : autour de Into the little hill p. 19 La voix à l’opéra p. 20 L’Opéra de Lille p. 23 L’Opéra : un lieu, un bâtiment et un vocabulaire 2 • • • Préparer votre venue Ce dossier vous aidera à préparer votre venue avec les élèves. L’équipe de l’Opéra de Lille est à votre disposition pour toute information complémentaire et pour vous aider dans votre approche pédagogique. Si le temps vous manque, nous vous conseillons, prioritairement, de : - écouter quelques extraits de l’opéra (guide d’écoute p. 8) - lire le projet de mise en scène (p. 14) Si vous souhaitez aller plus loin, un dvd pédagogique sur l’Opéra de Lille peut vous être envoyé sur demande. Les élèves pourront découvrir l’Opéra, son histoire, une visite virtuelle du bâtiment, ainsi que les différents spectacles présentés et des extraits musicaux et vidéo. -

Opera Today : Written on Skin at Lincoln Center

Opera Today : Written on Skin at Lincoln Center HOME COMMENTARY FEATURED OPERAS NEWS Aïda at Aspen Most opera professionals, including the individuals REPERTOIRE who do the casting for major houses, despair of REVIEWS finding performers who can match historical ABOUT standards of singing in operas such as Aïda. Yet a CONTACT concert performance in Aspen gives a glimmer of LINKS hope. It was led by four younger singers who may SEARCH SITE be part of the future of Verdi singing in America and the world. Prom 53: Shostakovich — Orango One might have been forgiven for thinking that both biology and chronology had gone askew at the Royal Albert Hall yesterday evening. Written on Skin at Lincoln Center Three years ago I made what may have been my single worst decision in a half century of attending Subscribe to opera. I wasn’t paying close attention when some Opera Today 28 Aug 2015 Receive articles and conference organizers in Aix-en-Provence offered news via RSS feeds or me two tickets to the premiere of a new opera. I email subscription. opted instead for what seemed like a sure thing: Written on Skin at Lincoln Center Feature Articles William Christie conducting some Charpentier. La Púrpura de la Rosa Advertised in the program as the first opera written Three years ago I made what may have been my single in the New World, La Púrpura de la Rosa (PR) was worst decision in a half century of attending opera. I premiered in 1701 in Lima (Peru), but more than the historical feat, true or not, accounts for the wasn’t paying close attention when some conference piece’s interest. -

Investigating New Models for Opera Development

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 INVESTIGATING NEW MODELS FOR OPERA DEVELOPMENT JULIAN MONTAGU PHILIPS DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSICAL COMPOSITION UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX SEPTEMBER 2010 (incorporating minor corrections as of April 2012) 2 PREFACE Since this doctoral submission accounts for a Composer-in-Residence scheme within the context of Glyndebourne Festival Opera in 2006-9, the bulk of this submission has grown out of collaborative relationships with writers, directors, performers and conductors. The most important collaborative partners include writers Simon Christmas, Edward Kemp and Nicky Singer; the directors Olivia Fuchs, Clare Whistler, Freddie Wake-Walker and John Fulljames, and the conductors Leo McFall and Nicholas Collon. In addition a host of young singers have contributed to this project’s final performance outputs; I am greatly indebted to all of them for their imagination, generosity and commitment. Aside from bibliographical sources detailed below (bibliography, page 360), other source material that has been fed into this submission includes interviews with Glyndebourne’s General Director, David Pickard, and an archiving of the extensive email development exchange out of which the chamber opera, The Yellow Sofa emerged (Appendix 13, p.