Research on Reader's Guides to Ming and Qing Popular Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopia/Wutuobang As a Travelling Marker of Time*

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/./), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:./SX UTOPIA/WUTUOBANG AS A TRAVELLING MARKER OF TIME* LORENZO ANDOLFATTO Heidelberg University ABSTRACT. This article argues for the understanding of ‘utopia’ as a cultural marker whose appearance in history is functional to the a posteriori chronologization (or typification) of historical time. I develop this argument via a comparative analysis of utopia between China and Europe. Utopia is a marker of modernity: the coinage of the word wutuobang (‘utopia’) in Chinese around is analogous and complementary to More’s invention of Utopia in ,inthatbothrepresent attempts at the conceptualizations of displaced imaginaries, encounters with radical forms of otherness – the European ‘discovery’ of the ‘New World’ during the Renaissance on the one hand, and early modern China’sown‘Westphalian’ refashioning on the other. In fact, a steady stream of utopian con- jecturing seems to mark the latter: from the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom borne out of the Opium wars, via the utopian tendencies of late Qing fiction in the works of literati such as Li Ruzhen, Biheguan Zhuren, Lu Shi’e, Wu Jianren, Xiaoran Yusheng, and Xu Zhiyan, to the reformer Kang Youwei’s monumental treatise Datong shu. -

Analysi of Dream of the Red Chamber

MULTIPLE AUTHORS DETECTION: A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER XIANFENG HU, YANG WANG, AND QIANG WU A bs t r a c t . Inspired by the authorship controversy of Dream of the Red Chamber and the applica- tion of machine learning in the study of literary stylometry, we develop a rigorous new method for the mathematical analysis of authorship by testing for a so-called chrono-divide in writing styles. Our method incorporates some of the latest advances in the study of authorship attribution, par- ticularly techniques from support vector machines. By introducing the notion of relative frequency as a feature ranking metric our method proves to be highly e↵ective and robust. Applying our method to the Cheng-Gao version of Dream of the Red Chamber has led to con- vincing if not irrefutable evidence that the first 80 chapters and the last 40 chapters of the book were written by two di↵erent authors. Furthermore, our analysis has unexpectedly provided strong support to the hypothesis that Chapter 67 was not the work of Cao Xueqin either. We have also tested our method to the other three Great Classical Novels in Chinese. As expected no chrono-divides have been found. This provides further evidence of the robustness of our method. 1. In t r o du c t ion Dream of the Red Chamber (˘¢â) by Cao Xueqin (˘»é) is one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. For more than one and a half centuries it has been widely acknowledged as the greatest literary masterpiece ever written in the history of Chinese literature. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

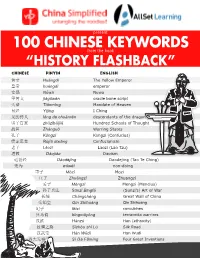

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

Interior, Only Escaping Back to Europe Years Later Through Bribery and the Help of Portuguese Merchants in Guangzhou

Contents Editorial 5 A Thousand Li Sorghum and Steel 11 The Socialist Developmental Regime and the Forging of China Introduction - Transitions 12 1 - Precedents 21 2 - Development 58 3 - Ossification 102 4 - Ruination 127 Conclusion - Unbinding 146 Gleaning the Welfare Fields 151 Rural Struggles in China since 1959 Revisiting the Wukan Uprising of 2011 183 An Interview with Zhuang Liehong No Way Forward, No Way Back 191 China in the Era of Riots “The Future is Hidden within these Realities” 229 Selected Translations from Factory Stories 1 - Preface to Issue #1 233 2 - One Day 235 3 - Layoffs and Labor Shortages 237 4 - Looking Back on 20 years in Shenzhen’s Factories 240 3 Editorial A Thousand Li As the Qing dynasty began its slow collapse, thousands of peasants were funneled into port cities to staff the bustling docks and sweatshops fueled by foreign silver. When these migrants died from the grueling work and casual violence of life in the treaty ports, their families often spent the sum of their remittances to ship the bodies home in a practice known as “transporting a corpse over a thousand li” (qian li xing shi), otherwise the souls would be lost and misfortune could befall the entire lineage. The logistics of this ceremony were complex. After blessings and reanimation rituals by a Taoist priest, “corpse drivers” would string the dead upright in single file along bamboo poles, shouldering the bamboo at either end so that, when they walked, the stiff bodies strung between them would appear to hop of their own accord. Travelling only at night, the corpse drivers would ring bells to warn off the living, since the sight of the dead migrants was thought to bring bad luck. -

Cultural Governance in Contemporary China: Popular Culture, Digital Technology, and the State

! ! ! ! CULTURAL GOVERNANCE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA: POPULAR CULTURE, DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY, AND THE STATE BY LUZHOU LI DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications and Media in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Emeritus John Nerone, Chair Assistant Professor Amanda Ciafone Professor Emeritus Dan Schiller Professor Kent Ono, University of Utah ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the historical formation and transformation of the Chinese online audiovisual industry under forces of strategic political calculations, expanding market relations, and growing social participation, and the cultural ramifications of this process, especially the kind of transformations digital technologies have wrought on the state-TV-station-centered mode of cultural production/distribution and regulatory apparatuses. Through this case, the project aims to theorize the changing mode of cultural governance of post-socialist regimes in the context of digital capitalism. Using mixed methods of documentary research, interviews with industry practitioners, participant observations of trade fairs/festivals, and critical discourse analyses of popular cultural texts, the study finds that the traditional broadcasting and the online video sectors are structured along two different political economic mechanisms. While the former is dominated by domestic capital and heavily regulated by state agencies, the latter is supported by transnational capital and less regulated. Digital technologies coupled with transnational capital thus generate new cultural flows, processes, and practices, which produces a heterogeneous and contested cultural sphere in the digital environment that substantially differs from the one created by traditional television. -

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: a Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: A Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in East Asian Studies April 2014 ©2014 Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Acknowledgements First of all, I thank Professor Ellen Widmer not only for her guidance and encouragement throughout this thesis process, but also for her support throughout my time here at Wellesley. Without her endless patience this study would have not been possible and I am forever grateful to be one of her advisees. I would also like to thank the Wellesley College East Asian Studies Department for giving me the opportunity to take on such a project and for challenging me to expand my horizons each and every day Sincerest thanks to my sisters away from home, Amy, Irene, Cristina, and Beatriz, for the many late night snacks, funny notes, and general reassurance during hard times. I would also like to thank Joe for never losing faith in my abilities and helping me stay motivated. Finally, many thanks to my family and friends back home. Your continued support through all of my endeavors and your ability to endure the seemingly endless thesis rambles has been invaluable to this experience. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: THE PAIRING OF WOOD AND GOLD Lin Daiyu ................................................................................................. -

Confucianism and Sun Yat-Sen's Views on Civilization

1 Confucianism and Sun Yat-sen’s Views on Civilization Teiichi KAWATA I. Introduction The Qing Dynasty, the last of China’s feudal monarchies, was shaken to its very foundations due to the impact of the West, which was symbolized by the cannon fire of the Opium War in 1840. This is because the 2,000-plus year old system that made Confucianism the state ideology from the time of Emperor Wu in the Earlier Han was easily defeated by England’s military might, which made rapid advances due to the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century. Here the history of modern China begins. In the century that followed, in the time that the old system transformed into socialist China, a multitude of intellectual problems sprung forth. Truly, if this period of 100-plus years were put in the terms of Western European intellectual history, themes of intellectual history spanning several centuries were compressed into this period. Namely, starting the Renaissance in the fifteenth century, the Religious Reformation of the sixteenth century, French Enlightenment philosophy of the seventeenth century, as well as the revolutionary thought of the American and French Revolutions in the eighteenth century, and German Idealism, from Hegel to Marx’s Communism, truly various things were adopted, and they sprouted and bloomed. In a sense, that period could be called a golden age of thought. For these thinkers, it was absolutely necessary to engage in the task of how to think about the China in which they lived, and how to change it. They needed to prepare answers to cultural problems such as China’s traditions versus China’s modernization, Chinese civilization versus Western civilization; political problems such as imperialism, constitutionalism, or 2 republicanism and capitalism or socialism. -

China (1750 –1918) Chinese Society Underwent Dramatic Transformations Between 1750 and 1918

Unit 2 Australia and Asia China (1750 –1918) Chinese society underwent dramatic transformations between 1750 and 1918. At the start of this period, China was a vast and powerful empire, dominating much of Asia. The emperor believed that China, as a superior civilisation, had little need for foreign contact. Foreign merchants were only permitted to trade from one Chinese port. By 1918, China was divided and weak. Foreign nations such as Britain, France and Japan had key trading ports and ‘spheres of influence’ within China. New ideas were spreading from the West, challenging Chinese traditions about education, the position of women and the right of the emperor to rule. chapter Source 1 An artist’s impression of Shanghai Harbour, C. 1875. Shanghai was one11 of the treaty ports established for British traders after China was defeated in the first Opium War (1839–42) 11A 11B 11C 11D What were the main features of What was the impact ofDRAFT How did the Chinese respond What was the situation in China Chinese society around 1750? Europeans on Chinese society to European influence? by 1918? 1 Chinese society was isolated from the rest of the from 1750 onwards? 1 The Chinese attempted to restrict foreign influence 1 By 1918, the Chinese emperor had been removed world, particularly the West. Suggest two possible and crush the opium trade, with little success. Why and a Chinese republic established in which the 1 One of the products that Western nations used, consequences of this isolation. do you think this was the case? nation’s leader was elected by the people. -

Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Gregory Adam Scott All Rights Reserved This work may be used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. For more information about that license, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. For other uses, please contact the author. ABSTRACT Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China 經典佛化: 民國初期佛教出版文化 Gregory Adam Scott 史瑞戈 In this dissertation I argue that print culture acted as a catalyst for change among Buddhists in modern China. Through examining major publication institutions, publishing projects, and their managers and contributors from the late nineteenth century to the 1920s, I show that the expansion of the scope and variety of printed works, as well as new the social structures surrounding publishing, substantially impacted the activity of Chinese Buddhists. In doing so I hope to contribute to ongoing discussions of the ‘revival’ of Chinese Buddhism in the modern period, and demonstrate that publishing, propelled by new print technologies and new forms of social organization, was a key field of interaction and communication for religious actors during this era, one that helped make possible the introduction and adoption of new forms of religious thought and practice. 本論文的論點是出版文化在近代中國佛教人物之中,扮演了變化觸媒的角色. 通過研究從十 九世紀末到二十世紀二十年代的主要的出版機構, 種類, 及其主辦人物與提供貢獻者, 論文 說明佛教印刷的多元化 以及範圍的大量擴展, 再加上跟出版有關的社會結構, 對中國佛教 人物的活動都發生了顯著的影響. 此研究顯示在被新印刷技術與新形式的社會結構的推進 下的出版事業, 為該時代的宗教人物展開一種新的相互連結與構通的場域, 因而使新的宗教 思想與實踐的引入成為可能. 此論文試圖對現行關於近代中國佛教的所謂'復興'的討論提出 貢獻. Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables iii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations and Conventions ix Works Cited by Abbreviation x Maps of Principle Locations xi Introduction Print Culture and Religion in Modern China 1. -

Bannerman and Townsman: Ethnic Tension in Nineteenth-Century Jiangnan

Bannerman and Townsman: Ethnic Tension in Nineteenth-Century Jiangnan Mark Elliott Late Imperial China, Volume 11, Number 1, June 1990, pp. 36-74 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/late.1990.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/late/summary/v011/11.1.elliott.html Access Provided by Harvard University at 02/16/13 5:36PM GMT Vol. 11, No. 1 Late Imperial ChinaJune 1990 BANNERMAN AND TOWNSMAN: ETHNIC TENSION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY JIANGNAN* Mark Elliott Introduction Anyone lucky enough on the morning of July 21, 1842, to escape the twenty-foot high, four-mile long walls surrounding the city of Zhenjiang would have beheld a depressing spectacle: the fall of the city to foreign invaders. Standing on a hill, looking northward across the city toward the Yangzi, he might have decried the masts of more than seventy British ships anchored in a thick nest on the river, or perhaps have noticed the strange shapes of the four armored steamships that, contrary to expecta- tions, had successfully penetrated the treacherous lower stretches of China's main waterway. Might have seen this, indeed, except that his view most likely would have been screened by the black clouds of smoke swirling up from one, then two, then three of the city's five gates, as fire spread to the guardtowers atop them. His ears dinned by the report of rifle and musket fire and the roar of cannon and rockets, he would scarcely have heard the sounds of panic as townsmen, including his own relatives and friends, screamed to be allowed to leave the city, whose gates had been held shut since the week before by order of the commander of * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Manchu Studies (Manzokushi kenkyùkai) at Meiji University, Tokyo, in November 1988. -

Translation As Rewriting: a Descriptive Study of Wang Jizhen’S1 Two Adapted Translations of Hongloumeng

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 10, No. 1, 2014, pp. 69-78 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020141001.4005 www.cscanada.org Translation as Rewriting: A Descriptive Study of Wang Jizhen’s1 Two Adapted Translations of Hongloumeng QIU Jin[a],*; QU Daodan[b]; DU Fenggang[c] 1 [a]Lecturer. School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of be ignored. Wang’s rewritings of Hongloumeng also Technology, Dalian, China. indicate that when translators go against the conditioning [b]Lecturer. School of English Studies, Dalian University of Foreign Languages, Dalian, China. factors, their subversion operates much more often on the [c]Professor. School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of poetical level than on the ideological level. Technology, Dalian, China. * Key words: Rewriting; Descriptive study; Adapted Corresponding author. translation; Hongloumeng; Ideology; Poetics Supported by National Social Science Program of China (No.13BYY032) and Provincial Social Science Program of Liaoning (No. QIU Jin, QU Daodan, & DU Fenggang (2014). Translation L13DYY057). as Rewriting: A Descriptive Study of Wang Jizhen’s Two Adapted Translations of Hongloumeng. Cross-Cultural Received 26 October 2013; accepted 14 January 2014 Communication, 10(1), 69-78. Available from: http//www.cscanada. net/index.php/ccc/article/view/j.ccc.1923670020141001.4005 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020141001.4005 Abstract Applying André Lefevere’s theory of rewriting to a descriptive study of the two adapted translations of Hongloumeng by Wang Jizhen published respectively INTRODUCTION in 1929 and 1958, this paper attempts to investigate the effects the dominant ideology and poetics in a given As one of the greatest classical novels in Chinese society at a given time have on the translator’s choice literature, Hongloumeng has been translated and of strategies in the translation process.