Pidgin and Hawai'i English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New England Phonology*

New England phonology* Naomi Nagy and Julie Roberts 1. Introduction The six states that make up New England (NE) are Vermont (VT), New Hampshire (NH), Maine (ME), Massachusetts (MA), Connecticut (CT), and Rhode Island (RI). Cases where speakers in these states exhibit differences from other American speakers and from each other will be discussed in this chapter. The major sources of phonological information regarding NE dialects are the Linguistic Atlas of New England (LANE) (Kurath 1939-43), and Kurath (1961), representing speech pat- terns from the fi rst half of the 20th century; and Labov, Ash and Boberg, (fc); Boberg (2001); Nagy, Roberts and Boberg (2000); Cassidy (1985) and Thomas (2001) describing more recent stages of the dialects. There is a split between eastern and western NE, and a north-south split within eastern NE. Eastern New England (ENE) comprises Maine (ME), New Hamp- shire (NH), eastern Massachusetts (MA), eastern Connecticut (CT) and Rhode Is- land (RI). Western New England (WNE) is made up of Vermont, and western MA and CT. The lines of division are illustrated in fi gure 1. Two major New England shibboleths are the “dropping” of post-vocalic r (as in [ka:] car and [ba:n] barn) and the low central vowel [a] in the BATH class, words like aunt and glass (Carver 1987: 21). It is not surprising that these two features are among the most famous dialect phenomena in the region, as both are characteristic of the “Boston accent,” and Boston, as we discuss below, is the major urban center of the area. However, neither pattern is found across all of New England, nor are they all there is to the well-known dialect group. -

Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure

LINGUISTICS - Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure PIDGINS AND CREOLES Genevieve Escure Department of English, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA Keywords: contact language, lingua franca, (post)creole continuum, basilect, mesolect, acrolect, substrate, superstrate, bioprogram, monogenesis, polygenesis, relexification, variability, code switching, covert prestige, overt prestige, colonization, identity, nativization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some general properties of pidgins and creoles 3. Pidgins: Incipient communication 3.1. Chinese Pidgin English 3.2. Russenorsk. 3.3. Hawaiian Pidgin English 4. Creoles: Expansion, stabilization and variability 4.1. Basilect 4.2. Acrolect 4.3. Mesolect 5. Theoretical models and current trends in PC studies 5.1. Early models 5.2. Developments of the substratist position 5.3. Developments of the universalist position: The bioprogram 6. The (post)creole continuum and decreolization 7. New trends 7.1. Sociohistorical evidence 7.2. Demographic explanations 7.3. Acquisition 8. Conclusion Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch UNESCO – EOLSS Summary Pidgins and creolesSAMPLE are languages that arose CHAPTERSin the context of temporary events (e.g., trade, seafaring, and even tourism), or enduring traumatic social situations such as slavery or wars. In the latter context, subjugated people were forced to create new languages for communication. Long stigmatized, those languages provide valuable insight into the mental mechanisms that enable individuals to use their innate capacity -

Downloaded an Applet That Would Allow the Recordings to Be Collected Remotely

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title A Survey of English Vowel Spaces of Asian American Californians Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4w84m8k4 Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 12(1) ISSN 2768-5047 Author Cheng, Andrew Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/P7121040736 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonetics and Phonology Lab Annual Report (2016) A Survey of English Vowel Spaces of Asian American Californians Andrew Cheng∗ May 2016 Abstract A phonetic study of the vowel spaces of 535 young speakers of Californian English showed that participation in the California Vowel Shift, a sound change unique to the West Coast region of the United States, varied depending on the speaker's self- identified ethnicity. For example, the fronting of the pre-nasal hand vowel varied by ethnicity, with White speakers participating the most and Chinese and South Asian speakers participating less. In another example, Korean and South Asian speakers of Californian English had a more fronted foot vowel than the White speakers. Overall, the study confirms that CVS is present in almost all young speakers of Californian English, although the degree of participation for any individual speaker is variable on account of several interdependent social factors. 1 Introduction This is a study on the English spoken by Americans of Asian descent living in California. Specifically, it will look at differences in vowel qualities between English speakers of various ethnic -

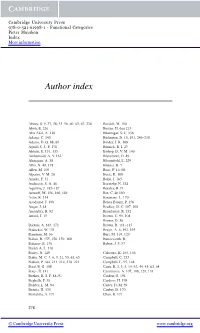

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61998-1 - Functional Categories Pieter Muysken Index More information Author index Abney, S. 9, 37, 38, 53–56, 60–63, 67, 228 Bersick, M. 108 Aboh, E. 226 Besten, H. den 213 Abu-Akel, A. 116 Bhatnagar, S. C. 136 Adams, C. 140 Bickerton, D. 10, 191, 246–250 Adams, D. Q. 88, 89 Binder, J. R. 108 Aguil´oS. J., F. 178 Binnick, R. I. 23 Ahls´en,E. 131, 135 Bishop, D. V. M. 140 Aikhenvald, A. Y. 162 Blakemore, D. 49 Akmajian, A. 58 Bloomfield, L. 229 Alb´o,X. 49, 178 Blutner, R. 7 Allen, M. 109 Boas, F. 14, 60 Alpatov, V. M. 28 Bock, K. 100 Ameka, F. 51 Bolle, J. 163 Anderson, S. A. 46 Boretzky, N. 224 Aquilina, J. 185–187 Borsley, R. D. Aronoff, M. 156, 160, 184 Bot, C. de 150 Aslin, R. 114 Boumans, L. 170 Asodanoe, J. 198 Boyes Braem, P. 156 Auger, J. 48 Bradley, D. C. 107, 108 Austerlitz, R. 92 Broadaway, R. 232 Award, J. 15 Brown, C. 99, 108 Brown, D. 36 Backus, A. 164, 172 Brown, R. 111–115 Badecker, W. 131 Bruyn, A. 6, 192, 193 Baerman, M. 36 Burt, M. 119, 120 Bahan, B. 155, 156, 159, 160 Butterworth, B. Baharav, E. 136 Bybee, J. 3, 57 Bailey A. L. 116 Bailey, N. 120 Calteaux, K. 165, 166 Baker, M. C. 4, 6, 9, 21, 53, 61, 65 Campbell, C. 233 Bakker, P. 184, 211–214, 218–221 Campbell, L. 95, 144 Bard, E. G. -

Anala Lb. Straine 2016 Nr.1

ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII BUCUREŞTI LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI STRĂINE 2016 – Nr. 1 SUMAR • SOMMAIRE • CONTENTS LINGVISTIC Ă / LINGUISTIQUE / LINGUISTICS ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş, Romanian Aspectual Verbs: Control and Restructuring ............... 3 COSTIN-VALENTIN OANCEA, The Category of Number in Present-Day English(es): Variation and Context ............................................................................................ 25 LEAH NACHMANI, EFL Teachers’ Perspectives on Reading Acquisition within a Multi-Cultural Learning Environment .................................................................. 41 ANDREI A. AVRAM, Diagnostic Features of English Pidgins/Creoles: New Evidence from West African Pidgin English and Krio ........................................................ 55 MIHAI CRUDU, Zum Lexem Herr und zu dessen Auftauchen in Wortbildungen und Phrasemen ............................................................................................................... 79 CAMELIA M ĂDĂLINA ŞTEFAN, On Latin-Old Swedish Language Contact through Loanwords ............................................................................................................... 89 * Recenzii • Comptes rendus • Reviews .................................................................................. 105 Contributors ........................................................................................................................ 111 ROMANIAN ASPECTUAL VERBS: CONTROL AND RESTRUCTURING ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş* Abstract The aim of the present paper is to investigate -

British Or American English?

Beteckning Department of Humanities and Social Sciences British or American English? - Attitudes, Awareness and Usage among Pupils in a Secondary School Ann-Kristin Alftberg June 2009 C-essay 15 credits English Linguistics English C Examiner: Gabriella Åhmansson, PhD Supervisor: Tore Nilsson, PhD Abstract The aim of this study is to find out which variety of English pupils in secondary school use, British or American English, if they are aware of their usage, and if there are differences between girls and boys. British English is normally the variety taught in school, but influences of American English due to exposure of different media are strong and have consequently a great impact on Swedish pupils. This study took place in a secondary school, and 33 pupils in grade 9 participated in the investigation. They filled in a questionnaire which investigated vocabulary, attitudes and awareness, and read a list of words out loud. The study showed that the pupils tend to use American English more than British English, in both vocabulary and pronunciation, and that all of the pupils mixed American and British features. A majority of the pupils had a higher preference for American English, particularly the boys, who also seemed to be more aware of which variety they use, and in general more aware of the differences between British and American English. Keywords: British English, American English, vocabulary, pronunciation, attitudes 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... -

Resource for Self-Determination Or Perpetuation of Linguistic Imposition: Examining the Impact of English Learner Classification Among Alaska Native Students

EdWorkingPaper No. 21-420 Resource for Self-Determination or Perpetuation of Linguistic Imposition: Examining the Impact of English Learner Classification among Alaska Native Students Ilana M. Umansky Manuel Vazquez Cano Lorna M. Porter University of Oregon University of Oregon University of Oregon Federal law defines eligibility for English learner (EL) classification differently for Indigenous students compared to non-Indigenous students. Indigenous students, unlike non-Indigenous students, are not required to have a non-English home or primary language. A critical question, therefore, is how EL classification impacts Indigenous students’ educational outcomes. This study explores this question for Alaska Native students, drawing on data from five Alaska school districts. Using a regression discontinuity design, we find evidence that among students who score near the EL classification threshold in kindergarten, EL classification has a large negative impact on Alaska Native students’ academic outcomes, especially in the 3rd and 4th grades. Negative impacts are not found for non-Alaska Native students in the same districts. VERSION: June 2021 Suggested citation: Umansky, Ilana, Manuel Vazquez Cano, and Lorna Porter. (2021). Resource for Self-Determination or Perpetuation of Linguistic Imposition: Examining the Impact of English Learner Classification among Alaska Native Students. (EdWorkingPaper: 21-420). Retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University: https://doi.org/10.26300/mym3-1t98 ALASKA NATIVE EL RD Resource for Self-Determination or Perpetuation of Linguistic Imposition: Examining the Impact of English Learner Classification among Alaska Native Students* Ilana M. Umansky Manuel Vazquez Cano Lorna M. Porter * As authors, we’d like to extend our gratitude and appreciation for meaningful discussion and feedback which shaped the intent, design, analysis, and writing of this study. -

A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect Ryan Wall [email protected]

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons HON499 projects Honors Program Fall 11-29-2017 A Jawn by Any Other Name: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect Ryan Wall [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the Other Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Wall, Ryan, "A Jawn by Any Other Name: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect" (2017). HON499 projects. 12. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects/12 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in HON499 projects by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Jawn by Any Other Name: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect Ryan Wall Honors 499 Fall 2017 RUNNING HEAD: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF THE PHILADELPHIA DIALECT 2 Introduction A walk down Market Street in Philadelphia is a truly immersive experience. It’s a sensory overload: a barrage of smells, sounds, and sights that greet any visitor in a truly Philadelphian way. It’s loud, proud, and in-your-face. Philadelphians aren’t known for being a quiet people—a trip to an Eagles game will quickly confirm that. The city has come to be defined by a multitude of iconic symbols, from the humble cheesesteak to the dignified Liberty Bell. But while “The City of Brotherly Love” evokes hundreds of associations, one is frequently overlooked: the Philadelphia Dialect. -

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity Karen Mattison Yabuno I. INTRODUCTION Hawaiian Creole English, commonly known as Pidgin, is widely spoken in Hawaii. In 2015, it was recognized by the US Census Bureau as a third official language of Hawaii, following English and Hawaiian(Laddaran, 2015). Pidgin is distinct and separate from Hawaii English(Drager, 2012), which is also widely spoken in Hawaii but not recognized as an official language of the state. Pidgin arose among immigrant groups on the pineapple plantations and was the dominant language of the workers’ children by the 1920’s(Tamura, 1993). Historically, an ability to speak Pidgin established one as ‘local’ to Hawaii, while English was seen to be part of the haole(Caucasian) identity (Drager, 2012). Although non-English speaking Caucasians also worked on the plantations, the term ‘local’ has come to mean those descended from Asian immigrant groups, as well as indigenous Hawaiians. These days, about half of the population of Hawaii speak Pidgin(Sakoda and Siegel, 2003). Caucasians born, raised, or residing in Hawaii may also understand and speak Pidgin. However, there can be a negative reaction to Caucasians speaking Pidgin, even when the Caucasians self-identify as ‘locals’. This is discussed in the YouTube video, Being White in Hawaii(Timahification, 2014), and parodied in the YouTube video, Hawaiian Haole(YouRight, 2016). Why is it offensive for a Caucasian to speak Pidgin? To answer this question, this paper will examine the parody video, Hawaiian Haole; ‘local’ ―189― Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity identity in Hawaii; and race in Hawaii. Finally, the viewpoints of three ‘local’ haole will be presented. -

Differences Between British and American English Introduction

Differences between British and American English Introduction British and American English can be differentiated in three ways: o Differences in language use conventions: meaning and spelling of words, grammar and punctuation differences. o Vocabulary: There are a number of important differences, particularly in business terminology. o Differences in the ways of using English dictated by the different cultural values of the two countries. Our clients choose between British or American English, and we then apply the conventions of the version consistently. Differences in language use conventions Here are some of the key differences in language use conventions. 1. Dates. In British English, the standard way of writing dates is to put the day of the month as a figure, then the month (either as a figure or spelled out) and then the year. For example, 19 September 1973 or 19.09.73. The standard way of writing dates in American English is to put the month first (either as a figure or spelled out), then the day of the month, and then the year. For example, September 19th 1973 or 9/19/73. Commas are also frequently inserted after the day of the month in the USA. For example, September 19, 1973. 2. o and ou. In British English, the standard way of writing words that might include either the letter o or the letters ou is to use the ou form. For example, colour, humour, honour, behaviour. The standard way of writing such words in American English is to use only o. For example, color, humor, honor, behavior. 3. -

Sounding Southern: Identities Expressed Through Language1

FEATURED ARTICLE Sounding Southern: Identities Expressed Through Language1 Irina Shport and Wendy Herd 2 “Where are you from?” is the question one often hears in innovations necessary to understand them, and the inter- the United States. Many English speakers from the South- play of sociolinguistic variables in identity expression ern United States can hardly avoid this question (similar through language. Elements typical to Southern speech to speakers of English as a second language) unless they are used selectively and creatively by individual Southern become bidialectal and learn to switch between a Southern speakers rather than as a stereotypical bundle that some accent and a more mainstream, Standard American accent, are accustomed to see in descriptions of Southern speech. as many Southerners nowadays do (to compare South- ern and Standard pronunciation of a bidialectal speaker, The Stabilized Representation of listen to Multimedia1 at acousticstoday.org/shportmm). Southern United States English Southern US English stands out among North American Comprehensive overviews and synthesis of acoustic English dialects as being talked about and stigmatized the research on Southern US English can be found in works most, similar to English spoken in New York City (Pres- such as the Atlas of North American English (ANAE; Labov ton, 1988). It is often portrayed in the media and public as et al., 2006) and the special issue on Southern US English having a Southern drawl, twang, nasal, or sing-song qual- of The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (Shport ity to it. These labels serve to stereotype Southern speech and Herd, 2020; Thomas, 2020). -

Pidgins and Creoles

12/7/2015 LNGT0101 Announcements Introduction to Linguistics • HW 4 sent to your inboxes. Average score is 45/50. • Final HW is due today, and then you can celebrate. • Any questions on your final papers? Lecture #23 Dec 7th, 2015 2 Announcements Word play! • I’ll give out course response forms on Wednesday. So, please be there to fill them out! • Photo today? 3 4 Ambiguity again! Today’s agenda • Discussion of pidgins and creoles. 5 6 1 12/7/2015 Language contact What is a pidgin? Creating language out of thin air: What is a creole? The case of Pidgins and Creoles 7 8 Origin of Hawaiian Pidgin A sample of Hawaiian Pidgin • http://sls.hawaii.edu/pidgin/whatIsPidgin.php • http://www.mauimagazine.net/Maui‐ Magazine/July‐August‐2015/Da‐State‐of‐da‐ State/ 9 10 How about we listen to this English‐based speech variety? • English‐based speech variety • How much did you understand? • Maybe we can try reading. Not sure it’ll help, but let’s try. 11 12 2 12/7/2015 Emergence of Pidgins and Creoles Pidginization areas • A pidgin is a system of communication used by people who do not know each other’s languages but need to communicate with one another for trading or other purposes. • By definition, then, a pidgin is not a natural language. It’s a made‐up “makeshift” language. Notice, crucially, that it does not have native speakers. 13 14 The lexicons of Pidgins are typically based Pidgins are linguistically on some dominant language simplified systems • While a pidgin is used by speakers of different • As you should expect, pidgins are very simple languages, it is typically based on the lexicon of what in their linguistic properties.