Thoughts on Animalcules; Or, a Glimpse of the Invisible World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reorganisation of Complex Ciliary Flows Around Regenerating Stentor

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/681908; this version posted June 26, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Reorganisation of complex ciliary flows around 2 regenerating Stentor coeruleus 1,8 3 Kirsty Y. Wan* , Sylvia K. Hürlimann2,8, Aidan M. Fenix4,5,8, 4 Rebecca M. McGillivary3,8, Tatyana Makushok3,8, Evan Burns6,9, 5 Janet Y. Sheung7,9, Wallace F. Marshall*3,8 6 1. Living Systems Institute, University of Exeter, Stocker Road, Exeter, UK 7 2. Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA 8 3. Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, UCSF, San Francisco, CA, USA 9 4. Department of Pathology, University of Washington, WA, USA 10 5. Center for Cardiovascular Biology, University of Washington, WA, USA 11 6. Department of Biology, Vassar College, NY, USA 12 7. Department of Physics and Astronomy, Vassar College, NY, USA 13 8. Marine Biological Laboratory, Physiology Course, Woods Hole, MA, USA 14 9. Marine Biological Laboratory, Whitman Center, Woods Hole, MA, USA 15 16 Keywords: Cilia coordination, metachronal waves, regeneration, development, ciliary flows, Stentor 17 18 19 Summary 20 21 The phenomenon of ciliary coordination has garnered increasing attention in recent decades, with multiple 22 theories accounting for its emergence in different contexts. The heterotrich ciliate Stentor coeruleus is a 23 unicellular organism which boasts a number of features which present unrivalled opportunities for 24 biophysical studies of cilia coordination. -

Tardigrades: an Imaging Approach, a Record of Occurrence, and A

TARDIGRADES: AN IMAGING APPROACH, A RECORD OF OCCURRENCE, AND A BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY By STEVEN LOUIS SCHULZE A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Science Graduate Program in Biology Written under the direction of Dr. John Dighton And approved by ____________________________ Dr. John Dighton ____________________________ Dr. William Saidel ____________________________ Dr. Emma Perry ____________________________ Dr. Jennifer Oberle Camden, New Jersey May 2020 THESIS ABSTRACT Tardigrades: An Imaging Approach, A Record of Occurrence, and a Biodiversity Inventory by STEVEN LOUIS SCHULZE Thesis Director: Dr. John Dighton Three unrelated studies that address several aspects of the biology of tardigrades— morphology, records of occurrence, and local biodiversity—are herein described. Chapter 1 is a collaborative effort and meant to provide supplementary scanning electron micrographs for a forthcoming description of a genus of tardigrade. Three micrographs illustrate the structures that will be used to distinguish this genus from its confamilials. An In toto lateral view presents the external structures relative to one another. A second micrograph shows a dentate collar at the distal end of each of the fourth pair of legs, a posterior sensory organ (cirrus E), basal spurs at the base of two of four claws on each leg, and a ventral plate. The third micrograph illustrates an appendage on the second leg (p2) of the animal and a lateral appendage (C′) at the posterior sinistral margin of the first paired plate (II). This image also reveals patterning on the plate margin and the leg. -

2-Microbe-Hunters-Paul-De-Kruif.Pdf

Microbe Hunters Paul de Kruif To RHEA A Harvest/HBJ Book Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers San Diego New York London Copyright 1926 by Paul de Kruif Copyright renewed 1954 by Paul de Kruif All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Table of Contents 1. LEEUWENHOEK: First of the Microbe Hunters 2. SPALLANZANI: Microbes Must Have Parents! 3. PASTEUR: Microbes Are a Menace! 4. KOCH: The Death Fighter 5. PASTEUR: And the Mad Dog 6. ROUX AND BEHRING: Massacre the Guinea-Pigs 7. METCHNIKOFF: The Nice Phagocytes 8. THEOBALD SMITH: Ticks and Texas Fever 9. BRUCE: Trail of the Tsetse 10. ROSS VS. GRASSI: Malaria 11. WALTER REED: In the Interest of Science-and for Humanity! 12. PAUL EHRLICH: The Magic Bullet Footnotes Books by Paul de Kruif 1. LEEUWENHOEK: First of the Microbe Hunters 1 Two hundred and fifty years ago an obscure man named Leeuwenhoek looked for the first time into a mysterious new world peopled with a thousand different kinds of tiny beings, some ferocious and deadly, others friendly and useful, many of them more important to mankind than any continent or archipelago. Leeuwenhoek, unsung and scarce remembered, is now almost as unknown as his strange little animals and plants were at the time he discovered them. This is the story of Leeuwenhoek, the first of the microbe hunters. It is the tale of the bold and persistent and curious explorers and fighters of death who came after him. -

Anton Van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723)

9 HISTOIRE DE L'ANDROLOGIE Andrologie 2004, 14, N~ 336-342 Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) et la premiere description du spermatozo'fde Georges ANDROUTSOS Histoire de la Medecine, Facult~ de M~decine, Universite d'loannina, Grece Ill lit ~~::; ,:.~: RESUME de travail entre sa boutique de tissus et le siege des Magistrats de Delft. II avait vingt-deux ans quand il epou- sa Barbara. Veuf douze ans plus tard, il ne se remaria pas Leeuwenhoek, p~re de la microscopie optique, est avant plusieurs annees. Des cinq enfants que lui laissait juste titre consid~r~ comme le fondateur de la bact~riolo- sa premiere femme, seule sa fille Maria surv6cut, demeu- gie et de la proto-zoologie. Son grand m~rite en mati~re ra aupres de lui et le soigna jusqu'a son dernier souffle, d'andrologie est d'avoir decouvert et ~tudi~ le spermato- apr~s la mort de sa seconde epouse. Leeuwenhoek mou- zo'ide. rut le 29 aoOt 1723. Sa fille lui fit elever un tombeau qu'on voit encore a Delft. Plusieurs annbes avant sa mort, Leeuwenhoek avait fabri- qu6 un joli cabinet de bois, comprenant plusieurs etage- res, destine a accueillir vingt six diffbrents modeles de microscopes, dont plusieurs portaient des lentilles mon- tees sur argent. Sa fille envoya le prbcieux meuble a la Royal Society oO il demeura pendant un siecle avant de disparaTtre mysterieusement. En dehors des microscopes partis pour Londres, Leeuwenhoek en possedait 247 aut- res, ainsi que 172 lentilles a monture d'or, d'argent ou de Mots clds : Leeuwenhoek, microscope, micro-organismes, cuivre [11]. -

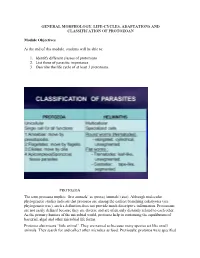

General Morphology, Life-Cycles, Adaptations and Classification of Protozoan

GENERAL MORPHOLOGY, LIFE-CYCLES, ADAPTATIONS AND CLASSIFICATION OF PROTOZOAN Module Objectives At the end of this module, students will be able to: 1. Identify different classes of protozoans 2. List those of parasitic importance 3. Describe the life cycle of at least 3 protozoans. PROTOZOA The term protozoa implies ‘first animals’ as (proto) 'animals' (zoa). Although molecular phylogenetic studies indicate that protozoa are among the earliest branching eukaryotes (see phylogenetic tree), such a definition does not provide much descriptive information. Protozoans are not easily defined because they are diverse and are often only distantly related to each other. As the primary hunters of the microbial world, protozoa help in continuing the equilibrium of bacterial, algal and other microbial life forms. Protozoa also means ‘little animal’. They are named so because many species act like small animals. They search for and collect other microbes as food. Previously, protozoa were specified as unicellular protists possessing animal-like characteristics such as the capability to move in water. Protists are a class of eukaryotic microorganisms which are a part of the kingdom Protista. Protozoa possess typical eukaryotic organelles and in general exhibit the typical features of other eukaryotic cells. For example, a membrane bound nucleus containing the chromosomes is found in all protozoan species. However, in many protozoan species some of the organelles may be absent, or are morphologically or functionally different from those found in other eukaryotes. In addition, many of the protozoa have organelles that are unique to a particular group of protozoa. The term ‘protozoan’ has become debatable. Modern science has shown that protozoans refer to a very complex group of organisms that do not form a clade or monophylum. -

Unit 1: Protista, Perazoa and Metazoa:General Characters and Classification Upto Class

CBCS 1ST SEM MAJOR : PAPER -1 UNIT 1: PROTISTA, PERAZOA AND METAZOA:GENERAL CHARACTERS AND CLASSIFICATION UPTO CLASS BY DR. LUNA PHUKAN PROTISTA, CHARACTERS AND CLASSIFICATION UPTO CLASS What are Protists? Protists are simple eukaryotic organisms that are neither plants nor animals or fungi. Protists are unicellular in nature but can also be found as a colony of cells. Most protists live in water, damp terrestrial environments, or even as parasites. The term ‘Protista’ is derived from the Greek word “protistos”, meaning “the very first“. These organisms are usually unicellular and the cell of these organisms contain a nucleus which is bound to the organelles. Some of them even possess structures that aid locomotion like flagella or cilia. KINGDOM PROTISTA Characteristics of Kingdom Protista The primary feature of all protists is that they are eukaryotic organisms. This means that they have a membrane-enclosed nucleus. Other characteristic features of Kingdom Protista are as follows: 1. These are usually aquatic, present in the soil or in areas with moisture. 2. Most protist species are unicellular organisms, however, there are a few multicellular protists such as kelp. Some species of kelp grow so large that they exceed over 100 feet in height. (Giant Kelp). 3. Just like any other eukaryotes, the cells of these species have a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles. 4. They may be autotrophic or heterotrophic in nature. An autotrophic organism can create their own food and survive. A heterotrophic organism, on the other hand, has to derive nutrition from other organisms such as plants or animals to survive. -

Who Invented the First Microscope?

Who Invented the first microscope? • Credit for the first microscope is usually given to Zacharias Jansen, in Middleburg, Holland, around the year 1595. Minor White 1 Magnification ~ 9x (barely qualifies as a microscope) 2 Robert Hooke Anton von Leeuwenhoek ~1670 Dutch tradesman 1632-1723 -no higher education Discovered the cell (looking at cork) Discovered: bacteria, sperm cells, blood cells… 3 4 1 Anton von Leeuwenhoek Anton von Leeuwenhoek • Single tiny lens an unbelievably great company of living "these little animals were, to my eye, more animalcules, a-swimming more nimbly than than ten thousand times smaller than the any I had ever seen up to this time. The animalcule which Swammerdam has biggest sort. bent their body into curves in portrayed, and called by the name of Water- going forwards. Moreover, the other flea, or Water-louse, which you can see alive animalcules were in such enormous numbers, and moving in water with the bare eyes.” that all the water. seemed to be alive. - letter to Royal Society 1678 Discovery of bacteria - In the mouth of old man who had never brushed his teeth! Magnification ~ 270X Magnification ~ 270X 5 6 Compound Microscope An example • Structure: Made of two lenses, • Suppose the focal length of the Objective and eyepiece objective is 12mm, and the object is – Objective: The object being viewed is placed at 13mm. The image is then placed just outside the focal length 156mm away from the lens and the of the objective lens. The magnification is intermediate image thus formed is 156/13 = 12 X real, inverted, and enlarged. -

Early History of Microbiology and Microbiological Methods

1 EARLY HISTORY OF MICROBIOLOGY AND MICROBIOLOGICAL METHODS Robert F. Guardino AAI Development Services Wilmington, N.C. USA INTRODUCTION The original title of this chapter was to be “History of Microbiological Methods.” This would seem to indicate that inquisitive minds were consciously attempting to develop new methods for a new field of science. Or perhaps they had a “for profit” motive as if they were working for a company driving them towards new markets or to increase their portfolio of patents from which to draw royalties. This could not be further from the truth. Rather, the history of microbiology is a story of some common folk and other rather peculiar individuals, janitors and hobbyists, amateur lens grinders and chemists, physicians and botanists, housewives and laboratory “slaves” with a quest for discovery. These explorers were sometimes driven by chance or curiosity, and sometimes by a problem for which no one had an answer. And, they were driven sometimes by pride or self-interest. But then there were those altruistic ones driven by the pure compassion for suffering humanity. With the topic being rather broad, and the space being somewhat limited, the scope had to be narrowed so this chapter has mutated into one that attempts to expose the minds behind the discoveries; 1 www.pda.org/bookstore 2 Encyclopedia of Rapid Microbiological Methods discoveries that necessitated the rather simple, though not always obvious, techniques that made revealing the world of microorganisms possible. The story that unfolds is first a history of events and phenomenon for which there was no understanding or explanation, followed by observations for which there was no obvious application, to the eventual association of cause and effect, on to a full blown field of inquiry. -

A Review. Historical Evolution of Preformistic Versus Neoformistic (Epigenetic) Thinking in Embryology

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228667377 A review. Historical evolution of preformistic versus neoformistic (epigenetic) thinking in embryology Article in Belgian Journal of Zoology · February 2008 CITATIONS READS 4 240 1 author: Callebaut Marc University of Antwerp 104 PUBLICATIONS 935 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Callebaut Marc letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 14 September 2016 Belg. J. Zool., 138 (1) : 20-35 January 2008 A review Historical evolution of preformistic versus neoformistic (epigenetic) thinking in embryology Marc Callebaut UA, Laboratory of Human Anatomy & Embryology, Groenenborgerlaan 171, B-2020 Antwerpen Belgium To the memory of Professor Doctor Lucien Vakaet sr Corresponding author : Prof. Dr Marc Callebaut, Laboratory of Human Anatomy and Embryology UA, 171 Groenenborgerlaan, B- 2020 Antwerpen. Phone: ++3232653390; fax: ++3232653398; e-mail. [email protected]. ABSTRACT. In the classical embryology there exist two main concepts to explain the rising of a living being. At one hand there exists the theory of preformation i.e. all the parts of the future embryo would already exist preformed during the preembryonic or early embryonic period. On the other hand there is the epigenetic view in which it is propounded that all parts arise by neoforma- tion from interacting (induction) previously existing, apparently simpler structures. We found evidence that initially a kind of pre- formation (or pre-existence), disposed in concentric circular layers, exists in the full grown oocyte and early germ. After normal development these circular layers will settle successively, from the centrum to the periphery, into the central nervous system, the notochord, somites, lateral plates (coelom) definitive endoderm. -

Microbe Hunters Paul De Kruif

Microbe Hunters Paul de Kruif To RHEA A Harvest/HBJ Book Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers San Diego New York London Copyright 1926 by Paul de Kruif Copyright renewed 1954 by Paul de Kruif All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Table of Contents 1. LEEUWENHOEK: First of the Microbe Hunters 1 2 3 4 2. SPALLANZANI: Microbes Must Have Parents! 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 3. PASTEUR: Microbes Are a Menace! 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 4. KOCH: The Death Fighter 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 5. PASTEUR: And the Mad Dog 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 6. ROUX AND BEHRING: Massacre the Guinea-Pigs 1 2 3 4 7. METCHNIKOFF: The Nice Phagocytes 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8. THEOBALD SMITH: Ticks and Texas Fever 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 9. BRUCE: Trail of the Tsetse 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10. ROSS VS. GRASSI: Malaria 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 11. WALTER REED: In the Interest of Science-and for Humanity! 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 12. PAUL EHRLICH: The Magic Bullet 1 2 3 4 5 6 Footnotes Books by Paul de Kruif 1. LEEUWENHOEK: First of the Microbe Hunters 1 Two hundred and fifty years ago an obscure man named Leeuwenhoek looked for the first time into a mysterious new world peopled with a thousand different kinds of tiny beings, some ferocious and deadly, others friendly and useful, many of them more important to mankind than any continent or archipelago. -

Type-Paramecium

Type-Paramecium Habit and habitat Paramecium caudatum is commonly found in freshwater ponds, pools, ditches, streams, lakes, reservoirs and rivers. It is specially found in abundance in stagnant ponds rich in decaying matter, in organic infusions, and in the sewage water. Paramecium caudatum is a free-living organism and this species is worldwide in distribution. Nutrition • In Paramecium caudatum, nutrition is holozoic. The food comprises chiefly bacteria and minute Protozoa. Paramecium does not wait for the food but hunts for it actively. • It is claimed that Paramecium caudatum shows a choice in the selection of its food, but there seems to be no basis for this though it engulfs only certain types of bacteria; available data suggest that 2 to 5 million individuals of Bacillus coli are devoured by a single Paramecium in 24 hours. It also feeds on unicellular plants like algae, diatoms, etc., and small bits of animals and vegetables. External features of Paramecium Size: Paramecium is a unicellular microscopic protozoan. The largest species of this genus is Paramecium caudatum and it measures about 170-290 µ. It is visible to naked eye as whitish or grayish spot. The greatest diameter of the cylindrical body is about two-thirds of its entire length. Shape: It is elongated, slipper-shaped animal and is commonly called as slipper animalcule due to its shape. The anterior end is rounded and the posterior end is cone-shaped. Ventral or oral surface is flat and the dorsal or aboral surface is convex. Pellicle • The body is covered by a thin, double layered, elastic and firm pellicle made of gelatin. -

Bacterial Biofilms: a Confrontation to Medical Science

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2015): 78.96 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Bacterial Biofilms: A Confrontation to Medical Science Sorabh Singh Sambyal1, Preeti Sharma2, Divya Srivastava3 1Ph.D Scholar, Jaipur National University 2Ph.D Scholar, Jaipur National University 3Joint Director, Life Sciences, Jaipur National University Abstract: Biofilms is a consortia of microorganisms in which microorganism adhere to a substratum in an irreversible manner and are enclosed in self – produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substance. Common example of biofilm are dental plaque, device associated infection. Mostly biofilms are infective in nature and can be a source of Nosocomial infection. According to a report published by national institute of Health about 65% of all microbial infections and 80% of all chronic infections are associated with biofilms. The structural anatomy of biofilms protects microbial cells from antimicrobial agents, UV rays. These biofilms act as a barrier; antibiotics cannot reach to these microbes hindering the killing of the microbes thus posing a serious threat to public health. Management of these bacterial biofilms requires an early detection method and development of novel and efficient control measures for treating patients improving patient care and timely management. Keywords: Biofilm, Biofilm-matrix Antimicrobial resistance, Polymeric Substances, Tissue-culture plate 1. Introduction London[9] In year 1933, Henrici presented his recorded observations concerning biofilms in which he observed that In nature, microorganism subsist primarily by adhering to water bacteria were not free floating, but they submerged and growing upon biotic and inanimate surfaces. These surface[8]. In year 1940, H.