The Study of the Avesta and Its Religion Around the Year 1900 and Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoroastrian Ethics by MA Buch

The Gnekwad Stu<Uc'^ in Rdi/tuii and Plcilu-^oph i/ : /I ZOKOASTRIAN ETHICS IVintod at the Mirfsion Press, Siirat l.y n. K. 8colt, and imblislieil l»y A. G. Wi(l;.'ery the Collej,'e, Baroda. I. V. 1919. ZOROASTHIAN ETHICS By MAGAXLAL A. BUCH, M. A. Fellow of the Seminar for the Comparative Stn<ly of IJelifjioiiP, Barotla, With an Infrnrhicfion hv ALBAN n. WrDGERY, ^f. A. Professor of Philosophy and of the Comparative Study of PiPlii^doiis, Baroda. B A K D A 515604 P n E F A C E The present small volume was undertaken as one subject of study as Fellow in the Seminar for the Comparative Study of Religions established in the College, Baroda, by His Highness the Maharaja Sayaji Eao Gaekwad, K C. S. I. etc. The subject was suggested by Professor Widgery who also guided the author in the plan and in the general working out of the theme. It is his hope that companion volumes on the ethical ideas associated with other religions will shortly be undertaken. Such ethical studies form an important part of the aim which His Highness had in view in establishing the Seminar. The chapter which treats of the religious conceptions is less elaborate than it might well have been, because Dr. Dhalla's masterly volume on Zomasfrirm Theolof/y^ New York, 1914, cannot be dispens- ed with by any genuine student of Zoroastrian- ism, and all important details may be learned from it. It only remains to thank I'rotessor Widgcrv lor writinf,' a L;enoral introduotion and for his continued help thronghont tho process of the work. -

Mecusi Geleneğinde Tektanrıcılık Ve Düalizm Ilişkisi

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ FELSEFE VE D İN B İLİMLER İ ANAB İLİM DALI DİNLER TAR İHİ B İLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZ İ MECUS İ GELENE Ğİ NDE TEKTANRICILIK VE DÜAL İZM İLİŞ KİSİ Mehmet ALICI (2502050181) Tez Danı şmanı: Prof.Dr. Şinasi GÜNDÜZ İstanbul 2011 T.C. İSTANBUL ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ FELSEFE VE D İN B İLİMLER İ ANAB İLİM DALI DİNLER TAR İHİ B İLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZ İ MECUS İ GELENE Ğİ NDE TEKTANRICILIK VE DÜAL İZM İLİŞ KİSİ Mehmet ALICI (2502050181) Tez Danı şmanı: Prof.Dr. Şinasi GÜNDÜZ (Bu tez İstanbul Üniversitesi Bilimsel Ara ştırma Projeleri Komisyonu tarafından desteklenmi ştir. Proje numarası:4247) İstanbul 2011 ÖZ Bu çalı şma Mecusi gelene ğinde tektanrıcılık ve düalizm ili şkisini ortaya çıkı şından günümüze kadarki tarihsel süreç içerisinde incelemeyi hedef edinir. Bu ba ğlamda Mecusilik üç temel teolojik süreç çerçevesinde ele alınmaktadır. Bu ba ğlamda birinci teolojik süreçte Mecusili ğin kurucusu addedilen Zerdü şt’ün kendisine atfedilen Gatha metninde tanrı Ahura Mazda çerçevesinde ortaya koydu ğu tanrı tasavvuru incelenmektedir. Burada Zerdü şt’ün anahtar kavram olarak belirledi ği tanrı Ahura Mazda ve onunla ili şkilendirilen di ğer ilahi figürlerin ili şkisi esas alınmaktadır. Zerdü şt sonrası Mecusi teolojisinin şekillendi ği Avesta metinleri ikinci teolojik süreci ihtiva etmektedir. Bu dönem Zerdü şt’ten önceki İran’ın tanrı tasavvurlarının yeniden kutsal metne yani Avesta’ya dahil edilme sürecini yansıtmaktadır. Dolayısıyla Avesta edebiyatı Zerdü şt sonrası dönü şen bir teolojiyi sunmaktadır. Bu noktada ba şta Ahura Mazda kavramı olmak üzere, Zerdü şt’ün Gatha’da ortaya koydu ğu mefhumların de ğişti ği görülmektedir. -

Zoroastrianism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Search Zoroastrianism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss Main page these issues on the talk page. Contents The neutrality of this article is disputed. (March 2012) Featured content This article may contain previously unpublished synthesis of Current events published material that conveys ideas not attributable to the Random article original sources. (March 2012) Donate to Wikipedia This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often Interaction accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (March 2012) Help Part of a series on About Wikipedia Zoroastrianism /ˌzɒroʊˈæstriənɪzəm/, also called Mazdaism Zoroastrianism Community portal and Magianism, is an ancient Iranian religion and a religious Recent changes philosophy. It was once the state religion of the Achaemenid, Contact page Parthian, and Sasanian empires. Estimates of the current number of Zoroastrians worldwide vary between 145,000 and Toolbox 2.6 million.[1] Print/export In the eastern part of ancient Persia more than a thousand The Faravahar, believed to be a depiction of a fravashi years BCE, a religious philosopher called Zoroaster simplified Languages Primary topics the pantheon of early Iranian gods[2] into two opposing forces: Afrikaans Ahura Mazda Ahura Mazda (Illuminating Wisdom) and Angra Mainyu Alemannisch Zarathustra (Destructive Spirit) which were in conflict. aša (asha) / arta Angels and demons ا open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Angels and demons ا Aragonés Zoroaster's ideas led to a formal religion bearing his name by Amesha Spentas · Yazatas about the 6th century BCE and have influenced other later Asturianu Ahuras · Daevas Azərbaycanca religions including Judaism, Gnosticism, Christianity and Angra Mainyu [3] Беларуская Islam. -

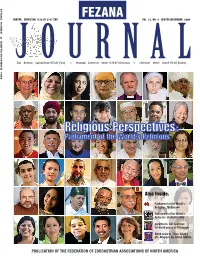

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA WINTER ZEMESTAN 1378 AY 3747 ZRE VOL. 23, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 JOURNALJODae – Behman – Spendarmad 1378 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1379 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1379 AY (Kadimi) Also Inside: Parliament oof the World’s Religions, Melbourne Parliamentt oof the World’s Religions:Religions: A shortshort hihistorystory Zarathustiss join in prayers for world peace in Pittsburgh Book revieew:w Thus Spake the Magavvs by Silloo Mehta PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA afezanajournal-winter2009-v15 page1-46.qxp 11/2/2009 5:01 PM Page 1 PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 4 Winter / December 2009 Zemestan 1378 AY - 3747 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 4ss Coming Event [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 5 FEZANA Update [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 16 Parliament of the World’s Religions Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] Yezdi Godiwalla [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] 47 In the News Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla -

Parsee Religious Ceremonial Objects in the United States National Museum

PARSES RELIGIOUS CEREMONIAL OBJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM.^ By I. M. Casanowicz, Assistant Curator, Division of Old ^VorUl Archeology, United States National Museum. INTRODUCTION. THE PABSEES. The Parsees are the descendants of the ancient Persians, who, at the overthrow of their country by the Arabs in G41 A. D., remained faithful to Zoroastrianism, which was, for centuries previous to the Mohammedan conquest, the state and national religion of Persia. They derive their name of Parsees from the province of Pars or Fars, broadly employed for Persia in general. According to the census of 1911 the number of Parsees in India, including Aden, the Andaman Islands, and Ceylon, the Straits Settlements, China, and Japan, amounted to 100,499, of whom 80,980 belonged to the Bombay Presidency.2 About 10,000 are scattered in their former homeland of Persia, mainly in Yezd and Kerman, where they are Imown by the name of Gebers, Guebers, or Gabars, derived by some from the Arabic Kafir, infidel. persian, zoroaster (avesta, zarathushtea ; pahlavi texts, zartdsht ; modern zaeddsht). The religious beliefs and practices of the Parsees are based on the is, teachings of Zoroaster, the Prophet of the ancient Iranians ; that those Aryans who at an unknown early date separated from the Aryo- Indians and spread from their old seats on the high plateau north of the Hindu Kush westward into Media and Persia on the great plateau between the plain of the Tigris in the west and the valley of the Indus in the east, the Caspian Sea and the Turanian desert in lA brief description of part of tlie collection described in this paper appeared in the American Anthropologist, new series, vol. -

Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices

Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices General Editor: John R. Hinnells The University, Manchester In the series: The Sikhs W. Owen Cole and Piara Singh Sambhi Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices MaryBoyce ROUTLEDGE & KEGAN PAUL London, Boston and Henley HARVARD UNIVERSITY, UBRARY.: DEe 1 81979 First published in 1979 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd 39 Store Street, London WC1E 7DD, Broadway House, Newtown Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EN and 9 Park Street, Boston, Mass. 02108, USA Set in 10 on 12pt Garamond and printed in Great Britain by Lowe & BrydonePrinters Ltd Thetford, Norfolk © Mary Boyce 1979 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Boyce, Mary Zoroastrians. - (Libraryof religious beliefs and practices). I. Zoroastrianism - History I. Title II. Series ISBN 0 7100 0121 5 Dedicated in gratitude to the memory of HECTOR MUNRO CHADWICK Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the University of Cambridge 1912-4 1 Contents Preface XJ1l Glossary xv Signs and abbreviations XIX \/ I The background I Introduction I The Indo-Iranians 2 The old religion 3 cult The J The gods 6 the 12 Death and hereafter Conclusion 16 2 Zoroaster and his teaching 17 Introduction 17 Zoroaster and his mission 18 Ahura Mazda and his Adversary 19 The heptad and the seven creations 21 .. vu Contents Creation and the Three Times 25 Death and the hereafter 27 3 The establishing of Mazda -

Languages of the Parsi Scriptures Author: Martin Haug Subtopics: I

Languages of The Parsi scriptures Author: Martin Haug Subtopics: I - The Language of the Avesta erroneously called Zend II - The Pahlavi language and Pazand, Texts of the Pahlavi Inscriptions at Hâjîâbâd H?J??B?D III -The Literature Extant ESSAY II. Languages of The Parsi scriptures The languages of Persia, commonly called Iranian, form a separate family of the great Aryan stock of languages which comprises, besides the Iranian idioms, Sanskrit (with its daughters), Greek, Latin, Teutonic (with English), Slavonian, Letto-Lithuanian, Celtic, and all allied dialects. The Iranian idioms arrange themselves under two heads: - Iranian languages properly so called. Affiliated tongues. The first division comprises the ancient, mediaeval, and modern languages of Iran, which includes Persia, Media, and Bactria, those lands which are styled in the Zend-Avesta airyâo danhâvô, “Aryan countries.” We may class them as follows: - (a.) The East Iranian or Bactrian branch, extant only in the two dialects in which the scanty fragments of the Parsi scriptures is written. The more ancient of them may be called the " Gatha dialect,” because the most extensive and important writings preserved in this peculiar idiom are the so-called Gathas or hymns; the later idiom, in which most of the books of the Zend-Avesta are written, may be called " ancient Bactrian,” or " the classical Avesta language,” which was for many centuries the spoken and written language of Bactria. The Bactrian languages seem to have been dying out in the third century B.C., and they have left no daughters. (b.) The West Iranian languages, or those of Media and Persia. -

Zoroastrianism by Annie Besant Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism by Annie Besant Zoroastrianism by Annie Besant A Convention Lecture at the 21st Anniversary of the Theosophical Society First printed in 1897 in the book Four Great Religions Reprinted in booklet form in 1935, 1959 The Theosophical Publishing House 1959 [Page 3] ONE of the differences which are continually arising between occult knowledge and the oriental science which has of late years been growing up in the West, is the question of the age of the great religions. When we come to Buddhism and to Christianity the difference is limited to the question of a century or two. But with regard both to Hinduism and Zoroastrianism, there is an entire conflict between orientalism and occultism — a clash which does not seem likely to cease: for most certainly the occultists will not change their position, and the Orientalists, on the other hand, are likely only to be driven backward stage by stage with the unveiling of ancient cities, with the discovery of ancient monuments. And this is a slow process. Hinduism and Zoroastrianism go back into what history would call "the night of time", Hinduism being the more ancient, and Zoroastrianism the second religion in the evolution of the Ãryan race. I propose to look at the changes of opinion through which Orientalists have passed, in order to show you how they are gradually being forced backwards, disputing, we may say, every inch of the ground, century after century, as the growing evidence points to an ever greater antiquity. Then I will take up the occult testimony [Page 4], and see where that places the religion of the Iranian Prophet. -

Nutrition Were Ancient Zoroastrians & Aryans Vegetarian?

NUTRITION WERE ANCIENT ZOROASTRIANS & ARYANS VEGETARIAN? K. E. Eduljee Zoroastrian Heritage Monographs First Aryan jashn, feast, in legend. King Hushang & the Feast of Sadeh celebrating the discovery of fire. Shahnameh manuscript of Ferdowsi's (Metropolitan Museumof Art). Image: In In Tahmasp Shah Image: Attributed to Artist Sultan Muhammad, Iran, Tabriz c. 1530 CE First edition published, September 2014. This second edition published, March 2015 by K. E. Eduljee West Vancouver, BC, Canada This monograph is dedicated to the memory of my mother Katayun Eduljee née Katayun Kaikhoshro Irani. Her brother, Darius Kaikhoshro Irani’s exemplary life-style choices inspired its writing. The monograph has been published in two versions: 1. Complete version with notations and source texts, 2. Abridged version without notations and source texts. For further enquiries and pdf or printed copies: [email protected] www.zoroastrianheritage.com This pdf copy in full form may be distributed freely. © K. E. Eduljee No part of this book may be reproduced in any other form without permission from the author, except for the quotation of brief passages in citation. Zoroastrian Heritage Monographs CONTENTS GLOSSARY .................................................................................................................................. viii IS THE TERM ‘ZOROASTRIAN’ ZOROASTRIAN? .................................................................... 1 THE MAGI ...................................................................................................................................... -

Sraosha - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

سروش http://www.arabdict.com/english-arabic/%D8%B3%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%B4 Sraosha - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sraosha Sraosha From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sraosha is the Avestan language name of the Zoroastrian yazata of "Obedience" or "Observance", which is also the literal meaning of his name. In the Middle Persian commentaries of the 9th-12th centuries, the divinity appears as S(a)rosh . This form Sor ūsh . Unlike many of the , وش appears in many variants in New Persian as well, for example Perso-Arabic other Yazatas (concepts that are "worthy of adoration"), Sraosha has the Vedic equivalent to Saraswati. Sraosha is also frequently referred to as the "Voice of Conscience", which overlaps with both "Obedience" and as his role as the "Teacher of Daena", Daena being the hypostasis of both "Conscience" and "Religion". Contents 1 In scripture 1.1 In Zoroaster's revelation 1.2 In the younger Avesta 2 In Zoroastrian tradition 3 References In scripture In Zoroaster's revelation Sraosha is already attested in the Gathas, the oldest texts of Zoroastrianism and believed to have been composed by Zoroaster himself. In these earliest texts, Sraosha is routinely associated with the Amesha Spentas, the six "Bounteous Immortals" through which Ahura Mazda realized ("created by His thought") creation. In the Gathas, Sraosha's primary function is to propagate the religion of Ahura Mazda to humanity, as Sraosha himself learned it from Ahura Mazda. This is only obliquely alluded to in these old verses but is only properly developed in later texts (Yasna 57.24, Yasht 11.14 etc.). -

THE BACKGROUND Retrospect: the Date of Zoroaster in the First Volume

CHAPTER ONE THE BACKGROUND Retrospect: the date of Zoroaster In the first volume of this history evidence was assembled which suggested that Zoroaster had lived in the turbulent times of the Iranian Heroic Age, when his people were one of numerous Iranian tribes in habiting the South Russian steppes. This period coincided broadly with the Iranian Bronze Age, held to extend from about IJOo-rooo B.C. Further reflection has led the writer to conclude that Zoroaster's own tribe must have been one which during this epoch still maintained a largely Stone-Age culture, at least during the prophet's formative years; for there is no suggestion in his Gathas that he himself recognised the existence of the characteristic tripartite society of the Bronze Age, with its division into herdsmen, priests and warriors 1-the last-named being the chariot-riders (rathaestar-) of the Younger Avesta, who were the 'heroes', devoting themselves to the pursuit of glory through fighting and raiding, hunting and drinking deep in rivalry with their peers. The society which emerges from the Gathas as the one which the prophet himself knew has an older, more stable pattern, that of a bi partite society with only the broad divisions of warrior-herdsmen and priests; 2 a pastoral society which looked upon itself as 'the collectivity of men and cattle together',3 pasu vira in the Avestan phrase, with every lay man expected to bear his part in caring for and protecting the herds; a society moreover which was ruled by laws formulated by its wise men, the priests, and which had no marked distinctions of rank among its members, since all men still went on foot about their daily affairs, and all could equip themselves, at expense only of skill and labour, with what weapons they needed-clubs and slingstones, stone-tipped arrows and spears, stone knives and axes. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2010 G SUMMER/JUNE 2010 JOURJO N AL Tir – Amordad – Shehrever 1379 AY (Fasli) G Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY, Fravardin 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Spendarmad 1379 AY, Fravardin – Ardibehesht 1380 AY (Kadimi) Dynamism of the Diaspora Building Zoroastrian Communities Around the World Also Inside: Progression of the Dynamism of the Diaspora in the U.K. Australian Diaspora Vibrant Communities New Zealand: in Hong Kong & Singapore Building a Legacy Photost : Constructition of Darbe Mehr in Dallas-Ft. Worth, Children’s performance in Houston. PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA VOL 24 No 2 Summer/June 2010 / Tabestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel 5 Financial Report Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 8 Coming Events [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, 4 FEZANA UPDATE ww.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 10 JUNGALWALLA LECTURE [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 16 DYNAMISM OF THE DIASPORA Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] Yezdi Godiwala [email protected] Fereshteh Khatibi: [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 113 IN THE NEWS Copy