The 4Th Pre-University Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monash University Foundation Year (Mufy)

MONASH UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION YEAR (MUFY) Student Guide 2020 MESSAGE FROM MONASH UNIVERSITY THE DIRECTOR FOUNDATION YEAR (MUFY) - A PREFERRED PATHWAY TO MONASH UNIVERSITY Welcome to the Monash community. I am delighted that you have chosen the Monash University Foundation Year or MUFY as the pathway to Monash University. Monash University, one of Australia’s prestigious Group of Eight universities, offers an outstanding learning experience. It is internationally recognised for its quality in research and excellence in teaching and learning. With a Monash education, you hold a passport to a promising career and a successful life ahead. MUFY is a pathway that provides the academic bridge The MUFY program which enjoys international recognition is the preferred university foundation for students to progress program for many Malaysian as well as international students. It offers students a smooth transition to successfully to undergraduate undergraduate studies and provides them with the foundation to excel at Monash University. studies at Monash University. Just as Monash is a passport to The MUFY curriculum is delivered on a blended learning format which combines face-to-face a fulfilling career and rewarding instruction with self-directed learning delivered on an e-learning platform. This enables students life, MUFY is the passport to to develop vital learning skills to cope with university studies and even life beyond university. By a rich learning experience equipping our students with the relevant tools to become independent learners, we aim to give them a at Monash. Designed by head-start in university, and ultimately, a promising and rewarding future. Monash academics, the MUFY program prepares students I wish you the best and hope you will enjoy the MUFY experience. -

Profile: the Center for American Education, Sunway University

Profile: The Center for American Education, Sunway University Address of Sunway University: Contact: Ms. Doreen John No. 5 Jalan Universiti, Head of Partnerships/Student Engagement Bandar Sunway Email: [email protected] 47500 Selangor, Malaysia Phone: +603 7491-8622 (Ext. 7204) Website: https://university.sunway.edu.my/ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Vice-Chancellor: Professor Graeme Wilkinson Provost: Professor Peter John Heard Head of the Center for American Education: Dr. Sim Tze Ying Sunway University is a private not-for-profit university that is owned and governed by the Jeffrey Cheah Foundation. Sunway University offers tertiary education leading to Bachelor’s, Master’s and PhD degrees in various fields of study. The American Degree Transfer Program (ADTP) is a unique transfer program offered in Sunway University. Vision: To be a world-class university Mission: To nurture individuals holistically through devotion to the discovery, advancement, transmission and application of knowledge that meets the needs of society and the global community Creed: Encourages achieving our Mission with integrity and unwavering Dedication to excellence, enterprise, professionalism, financial self-reliance, innovation, mutual respect and team spirit Values: Integrity, excellence and humility Sunway University’s Educational Goals: Sunway University students will: • become independent, lifelong learners who actively pursue knowledge and appreciate its global application to economic, political, social and cultural development • be empowered with the competencies and capacity to contribute to a fast-changing economic, social and technological world • develop strong leadership qualities and communication skills • be prepared for careers that enable them to lead productive, fulfilling and meaningful lives • value integrity and become ethical, accountable, caring and responsible members of society History: The ADTP was birthed in 1987 as a Twinning Program with Western Michigan University in Sunway College. -

Up2 V02 06 Small.Pdf

MAGAZINE / VOL 02 ISSUE 06 / Sep 2012 KKDN No. Permit: PP17565/11/2012 (031108) Moving up the next level Telling it from the heart Being a blessing to the less privileged Learning about business and charity Accountants with a heart A celebration of trailblazing education with SEE 2012 VO L 0 Advisor : Should you have comments, kindly contact: 2 I SS The Public Relations Department U Elizabeth Lee E Sunway Education Group 0 6 Tel: 603-7491 8622 / Editorial Team : S e [email protected] p Jerrine Koay www.sunway.edu.my/college (Editor) 2 0 1 Jacqueline Muriel Lim 2 (Sub-Editor & Writer) Disclaimer: Laveenia Theertha Pathy The views and opinions expressed or (Writer) implied in are those of the authors or contributors and do not necessarily reflect Publisher : those of Sunway Education Group. Sunway Education Group is published four times a year. The name was selected by popular Concept + Design : choice by the students themselves to represent a progressive Sunway Yoong & Ng Consulting College, an institution owned and governed by the Jeffrey Cheah Foundation. Since its inception in 1986, Sunway College has always Printer: been a leading private institution of higher learning, and it is forever Ocean Transfer (M) Sdn Bhd escalating into the next level of excellence. or UPP stands for “Uniquely Purposeful Programmes”. The Sunway Education Group institutions and services are :- Sunway International School Sunway College Ipoh Sunway University Sunway International Business & Tel: 603-7491 8622 Tel: 605-545 4398 Tel: 603-7491 8622 Management [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: 603-7493 7023 www.sis.sunway.edu.my www.sunway.edu.my/ipoh sunway.edu.my/university [email protected] www.sibm.com.my Sunway College Monash University Sunway Sunway College Kuching Tel: 603-5638 7176 campus Shanghai Sunway Financial Tel: (6082) 232 780/236 666 [email protected] Tel: 603-5514 6000 Training Co. -

IJISRT19AUG817 by Ijisrt19aug817 Ijisrt19aug817

IJISRT19AUG817 by Ijisrt19aug817 Ijisrt19aug817 Submission date: 26-Aug-2019 05:44PM (UTC+0530) Submission ID: 1163590850 File name: 1566471615_1.docx (204.71K) Word count: 7064 Character count: 41771 IJISRT19AUG817 ORIGINALITY REPORT 36% 25% 16% 34% SIMILARITY INDEX INTERNET SOURCES PUBLICATIONS STUDENT PAPERS PRIMARY SOURCES Submitted to MFH International Institute 1 Student Paper 3% vdocuments.site 2 Internet Source 2% issuu.com 3 Internet Source 1% Submitted to University of Northampton 4 Student Paper 1% Submitted to Segi University College 5 Student Paper 1% www.diva-portal.org 6 Internet Source 1% docplayer.net 7 Internet Source 1% www.emeraldinsight.com 8 Internet Source 1% www.ukessays.com 9 Internet Source 1% Submitted to University of Bahrain 10 Student Paper 1% www.ccsenet.org 11 Internet Source 1% Submitted to University of Wolverhampton 12 Student Paper 1% Submitted to University of Liverpool 13 Student Paper 1% Submitted to Middlesex University 14 Student Paper 1% www.tandfonline.com 15 Internet Source <1% www.ijbssnet.com 16 Internet Source <1% Submitted to The University of the South Pacific 17 Student Paper <1% Submitted to Leeds Metropolitan University 18 Student Paper <1% www.scholarpublishing.org 19 Internet Source <1% Submitted to Higher Education Commission 20 % Pakistan <1 Student Paper etd.uum.edu.my Internet Source Internet Source 21 <1% Submitted to University of Central England in 22 % Birmingham <1 Student Paper Submitted to Universiti Teknologi MARA 23 Student Paper <1% Submitted to Assumption University -

SUNWAY FOUNDATION PROGRAMME Foundation in Arts (FIA) Student Guide 2020 MESSAGE from the DIRECTOR PROGRAMME OUTLINE

SUNWAY FOUNDATION PROGRAMME Foundation in Arts (FIA) Student Guide 2020 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR PROGRAMME OUTLINE Welcome to the Sunway Foundation Programme at Sunway College. This programme believes in holistic education. This Core Units Academic Electives Enrichment Units means that, coupled with academic knowledge you will be exposed to experiential learning as an integral part of your well-rounded education. We are committed to moulding and COMPULSORY Choose 4 units ONLY COMPULSORY shaping students who have a balanced world view and an understanding of social issues and world affairs outside of just text books. Our emphasis is not confined to your doing • Language and • Introduction to Accounting • Culture: Arts & well in examinations and moving on to tertiary studies but in Communication Techniques Expressions developing your love for life-long learning, your confidence • Communication: • Accounting Processes and • Critical Thinking Skills in your own ability and finding your own talents. Enjoy this Audience and Context Reports • Introduction to journey where you chart your own success. Good luck! • Language and • Introduction to Business: Psychology Knowledge World of Finance Suzana Ahmad Ramli Director of Programme Sunway Foundation Programme • Contemporary Business • Microeconomics: Concepts Mathematics and Models • Mathematical • Macroeconomics: The Global Techniques and Analysis View FOUNDATION IN ARTS • Statistical Techniques • Introduction to Business: Management and Marketing OR • Mathematics for Actuarial An academic bridge -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

Enjoying Effortless Excellence

- FACE TO FACE - CONTENTS ENJOYING EFFORTLESS EXCELLENCE Face To Face The Sunway Education Group Starting end of February, 03 Enjoying Effortless Excellence Sunway College Ng Jee Hong is pursuing a 04 Volunteering Is Its Own Reward No. 2, Jalan Universiti Bachelor of Design majoring in 06 I Heart NYU Bandar Sunway 47500 Selangor Darul Ehsan Architecture at the Melbourne 08 A Platform For Learning And Malaysia School of Design, the University Earning Ideas T: 603-5638 7176 of Melbourne. A Monash Reinvent To Create 12 E: [email protected] University Foundation Year New Beginnings sunway.edu.my/college (MUFY) alumnus, Jee Hong 14 Teaching Is My Life! Sunway University plans to pursue a Master of Making A Difference In The Lives T: 603-7491 8622 Architecture for another 2 Of Others E: [email protected] years after completing his 15 In The Pacific Northwest sunway.edu.my/university Bachelor of Design. Monash University Malaysia 10 Victoria University Homecoming T: 603-5514 6000 E: [email protected] He thinks Architecture may Movers & Shakers monash.edu.my be the perfect course as he 07 The Big Five Increases enjoys studying concepts Engagement With Students Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences of physics behind the 13 Adding Colour To Academia T: 603-5514 6000 construction of buildings. At 16 Breeze Or Storm, MUFY E: [email protected] the same time, he will be able Graduates Shine Again med.monash.edu.my to use his ideas to create 17 Starting The Year With Sunway International School structures that excel practically A Great Celebration T: 603-7491 8070 and design-wise. -

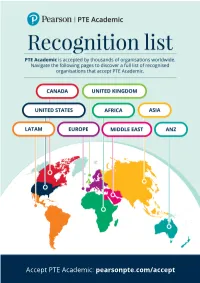

Global Recognition List August

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept Africa Egypt • Global Academic Foundation - Hosting university of Hertfordshire • Misr University for Science & Technology Libya • International School Benghazi Nigeria • Stratford Academy Somalia • Admas University South Africa • University of Cape Town Uganda • College of Business & Development Studies Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept August 2021 Africa Technology & Technology • Abbey College Australia • Australian College of Sport & Australia • Abbott School of Business Fitness • Ability Education - Sydney • Australian College of Technology Australian Capital • Academies Australasia • Australian Department of • Academy of English Immigration and Border Protection Territory • Academy of Information • Australian Ideal College (AIC) • Australasian Osteopathic Technology • Australian Institute of Commerce Accreditation Council (AOAC) • Academy of Social Sciences and Language • Australian Capital Group (Capital • ACN - Australian Campus Network • Australian Institute of Music College) • Administrative Appeals Tribunal • Australian International College of • Australian National University • Advance English English (AICE) (ANU) • Alphacrucis College • Australian International High • Australian Nursing and Midwifery • Apex Institute of Education School Accreditation Council (ANMAC) • APM College of Business and • Australian Pacific College • Canberra Institute of Technology Communication • Australian Pilot Training Alliance • Canberra. Create your future - ACT • ARC - Accountants Resource -

Our Partner Institutions List Study Abroad, Study Locally Or Both : the Choice Is Yours

SELSET Education Centre : Our Partner Institutions List Study Abroad, Study Locally or Both : The Choice is Yours NEW ZEALAND________________________________________________________________ Universities: - University of Auckland - AUT University - University of Waikato - Massey University - Victoria University of Wellington - University of Canterbury - Lincoln University - University of Otago Institute of Technology: - Toi Ohomai - ARA Institute of Canterbury - Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT) - Manukau Institute of Technology (MIT) - Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology (NMIT) - Open Polytechnic of New Zealand - Otago Polytechnic - Southern Institute of Technology (SIT) - Universal College of Learning (UCOL) - Unitec Institute of Technology - Waikato Institute of Technology (WINTEC) - Wellington Institute of Technology (WELTEC) - Whitireia New Zealand Private Institutions: - Aspire2 Group - New Zealand Tertiary College (NZTC) - Whitecliffe College of Arts & Design - Media Design School, Auckland - New Zealand School of Education - Pacific International Hotel Management School (PIHMS) - IPC Tertiary Institute - International Travel College (ITC) - Queenstown Resort College (QRC) - New Zealand School of Education (NZSE) - AGI Education - Royal Business College - Eagle Flight Training School - Air New Zealand Aviation Institute - Wellpark School of Natural Therapies Colleges and Schools: - ACG College Groups – For Foundation Studies, Secondary and Primary schools, Vocational Programs including New Zealand Careers College, NZMA, -

Cambridge GCE Advanced-Level (A-Level) Message from the Director

CAMBRIDGE GCE ADVANCED-LEVEL (A-LEVEL) MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Welcome to the Cambridge GCE A-Level Programme at counsellors from our Sunway College. Pre-University is an important crossroad, university placement so choose well. A Sunway College A-Level qualification centre further support not only brings you a step closer to attaining your goals you in your university but also opens up a world of possibilities. Here in the application journey. Sunway A-Level programme, we work with you to realise your goals. In addition to an intellectually stimulating academic environment, we provide you with ample opportunities Our consistent track record and excellent results are to participate in extracurricular activities. In the Sunway testimony to what you will experience here. This is in College A-Level Programme, we encourage your holistic recognition of our excellent delivery system, consistent development. academic performance and attainment of Cambridge Top in the World awards. We are extremely proud of our students and their individual success stories. We are also very proud of Pursuing the Cambridge A-Level qualification will be what they go on to achieve. I look forward to welcoming exciting and rewarding as you prepare for admission to you to the programme and to working with you to ensure universities worldwide, including top-tiered institutions. you too leave as successful individuals fully prepared Students before you have successfully entered premier for university and able to meet future challenges with universities in the world like Cambridge, Oxford, Imperial, confidence. the London School of Economics, Harvard and MIT. Your lecturers and academic mentors will guide you in your academic work and advise you on how you can benefit Ruth Cheah from the wide range of learning facilities and support Director of Programme services available at Sunway College. -

Sunway Students Are Top Scorers for Monash University Foundation Year

CONTENTS The Sunway Education Group Sunway University T: 603-7491 8622 E: [email protected] www.sunway.edu.my/university Sunway College T: 603-5638 7176 E: [email protected] www.sunway.edu.my/college Monash University Sunway Campus T: 603-5514 6000 E: [email protected] www.monash.edu.my Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences T: 603-5514 6000 WONDERLAND OF DISCOVERIES E: [email protected] 04 www.med.monash.edu.my MOVERS & SHAKERS 06 Leading Accountancy Hub by 2020 Sunway International School T: 603-7491 8070 07 45th Graduation for CIMP E: [email protected] 08 Top in the World and Malaysia: Sunway A Levels www.sis.sunway.edu.my 09 Sooo...I Graduated from AUSMAT Sunway College Johor Bahru 13 Sunway Students are Top Scorers for MUFY T: 607-359 6880 14 Foundation in Arts Alumni Share E: [email protected] Their Experience www.sunway.edu.my/jb 10 TYCOONS IN THE MAKING Sunway College Ipoh T: 605-545 4398 SOCIAL REPORT E: [email protected] 15 Carif’s Be Frank: Youth Programme Top Prize www.sunway.edu.my/ipoh Goes to Sunway Sunway College Kuching 16 Changing the Taxi Landscape-MyTeksi T: 6082-232 780/236 666 Delivering Happiness E: [email protected] www.swck.edu.my 17 Best and Brightest Receive Pre-University Scholarships Sunway TES Sharity Carnival by MUFY 18 T: 603-7491 8622 EXPLORING THE 8 STAGES E: [email protected] 19 www.sunway.edu.my/college/sunwaytes OF GENOCIDE Sunway International Business * Cover photo courtesy of AUSMAT students & Management T: 603-7493 7023 2 UP or UPP or Uniquely Purposeful Programmes is a quarterly publication that E: [email protected] represents a progressive Sunway College. -

Breaking the Boundaries Review Dear CIMA Members and Students

2011 January - December Breaking the boundaries review Dear CIMA members and students The year started on an exciting note with a new management team and a streamlining of staff functions across the board. Having passed the year end mark, the team at CIMA Malaysia presents its report on the activities that took place during the year 2011. Student growth started on a positive note in the first half of Naturally, members’ CPD needs were met through training the year and targets were exceeded by the year end. New programmes and evening talks, and communications with business opportunities presented themselves through our members and students stayed active via CIMA Malaysia’s close collaboration with institutions including Universiti Facebook page and e-Momentum, the bi-monthly online Sains Malaysia, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Universiti Teknologi newsletter. MARA, Sunway-TES, Sunway University and Sunway College Kuching, TAR College, UCSI University and Noesis. From a big picture perspective, the South East Asia Regional Board has been set up to help deliver CIMA Council’s CIMA’s new products such as the CIMA Diploma and objectives for growth globally. The joint venture between Advanced Diploma in Islamic Finance, CIMA Gateway CIMA and the American Institute of Certified Public Assessment for ACCA members and affiliates, and the CIMA Accountants will introduce the new Chartered Global Masters Gateway Assessment for MBA holders added to our Management Accountant (CGMA) designation for members student recruitment. Employers too played a key role in our in early 2012. strategy for growth and we have worked with selected major employers to promote the CIMA qualification.