Religious Identity and Political Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Democracy

Democracy on the Scale of Islam Religious Democracy www.ziaraat.com Sabeel-e-Sakina Mohammad Bagher Khorramshadi ICRO 1 Presented by Ziaraat.Com Religious Democracy -------------------------------------------- A Collection of Nine Articles About Religious Democracy in Islam Presented to the International Fourum of Religious Democracy- Tehran Mohammad Bagher Khorramshad With www.ziaraat.comDr. Ahmad Va’ezi Sabeel-e-SakinaAbdolhamid Akuchkian Dr. Mohsen Esma’ili Dr. Masood Akhavan Kazemi Dr. Bahram Nawazeni Dr. Ali Larijani Dr. Bahram Akhavan Kazemi 2 Presented by Ziaraat.Com Table of Contents Table of Contents.. … … … … … … … … … … …. … .. .. … .. .. … … .. .. … Intruduction … .. .. … … … .. .. .. … … … .. .. … .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. … .. .. .. … .. .. Preface:… … … … … … … … .. … .. … … .. … … …. … … … … … …. …. 1- Prelude (By Dr. Mohammad Bagher Khorramshad) …. …. …. ….. …. ….. …. …. …. 2 2- Theocratic Democracy and its Critics (By Dr. Ahmad Va’ezi) … …. …. … …. …. … ...6 .. .. … .. … … … .. … .. …. … ….. .. … … .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. …. … .. ..6 1- General Criticism on Guardianship Governances .. .. … .. … … … .. … .. …. … ….. .. 2 – A Paradoxical Sample of Theocratic Democracy … …. …. …. ….. ….. ….. …. …. ….. … 3 – Contradiction between Democracy and Islam … ….. ….. ….. ….. …. ….. …. …. ….. 4 – Theocratic Democracy and Problem of Legal Equality … …. ….. ….. …. ….. ….. ….. …. … 5- Incompetence of Jurist Management … …. …… ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. …. …. …. …. Afterword .. .. … .. … … … .. … .. …. … ….. .. … … .. .. . -

Dr Hedgewar and Sangh April 18 2018 Charcha

Date Topic April 04 2018 Samachar Sameeksha Baudhik –Dr Hedgewar and April 11 2018 Sangh April 18 2018 Charcha :-Moulding Men Katha :-Pujya Adi April 25 2018 Shankaracharya April 04 2018 : Samachar Sameeksha April 11 2018 : Baudhik :-Dr Hedgewar and Sangh ( Article by Swargiya K Suryanarayana Rao ji who was a senior Pracharak and Akhil Bharatiya Karyakarta ) Intro: The daily shakha system of imparting knowledge of character and discipline, removing all the weeds that were dividing the ancient society, to build up an indomitable organised strong Hindu society is RSS founder Dr Hedgewar’s greatest and unique contribution and service to his motherland. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is a very well known organisation. Decades ago, the BBC announced that it is the most wide spread and biggest non-governmental voluntary organisation which is working in India for Hindu consolidation. Since then RSS has grown and spread in multiple proportions. But still, very few, outside sangh circles, know about the founder of this mighty organisation, Dr Keshavrao Balirampanth Hedgewar, popularly known as ‘Doctorji’. Dr Hedgewar was a born patriot, and this instinctive patriotism burst forth at an early age of eight when he threw away the sweets distributed to the school children on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of British Queen Victoria. There are many such occasions which reflect how he grew up manifesting his patriotic nature. He intensely felt that our motherland must be freed from the foreign yoke at any cost and so worked zealously to achieve it by working with revolutionaries, Indian National Congress and Hindu Maha Sabha. -

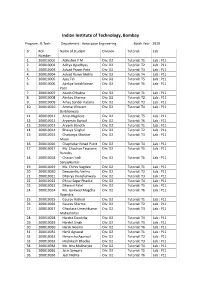

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Guardian Politics in Iran: a Comparative Inquiry Into the Dynamics of Regime Survival

GUARDIAN POLITICS IN IRAN: A COMPARATIVE INQUIRY INTO THE DYNAMICS OF REGIME SURVIVAL A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Payam Mohseni, M.A. Washington, DC June 22, 2012 Copyright 2012 by Payam Mohseni All Rights Reserved ii GUARDIAN POLITICS IN IRAN: A COMPARATIVE INQUIRY INTO THE DYNAMICS OF REGIME SURVIVAL Payam Mohseni, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Daniel Brumberg, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The Iranian regime has repeatedly demonstrated a singular institutional resiliency that has been absent in other countries where “colored revolutions” have succeeded in overturning incumbents, such as Ukraine, Georgia, Serbia, Kyrgyzstan and Moldova, or where popular uprisings like the current Arab Spring have brought down despots or upended authoritarian political landscapes, including Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen, Libya and even Syria. Moreover, it has accomplished this feat without a ruling political party, considered by most scholars to be the key to stable authoritarianism. Why has the Iranian political system proven so durable? Moreover, can the explanation for such durability advance a more deductive science of authoritarian rule? My dissertation places Iran within the context of guardian regimes—or hybrid regimes with ideological military, clerical or monarchical institutions steeped in the politics of the state, such as Turkey and Thailand—to explain the durability of unstable polities that should be theoretically prone to collapse. “Hybrid” regimes that combine competitive elections with nondemocratic forms of rule have proven to be highly volatile and their average longevity is significantly shorter than that of other regime types. -

Formative Years

CHAPTER 1 Formative Years Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a seaside town in western India. At that time, India was under the British raj (rule). The British presence in India dated from the early seventeenth century, when the English East India Company (EIC) first arrived there. India was then ruled by the Mughals, a Muslim dynasty governing India since 1526. By the end of the eighteenth century, the EIC had established itself as the paramount power in India, although the Mughals continued to be the official rulers. However, the EIC’s mismanagement of the Indian affairs and the corruption among its employees prompted the British crown to take over the rule of the Indian subcontinent in 1858. In that year the British also deposed Bahadur Shah, the last of the Mughal emperors, and by the Queen’s proclamation made Indians the subjects of the British monarch. Victoria, who was simply the Queen of England, was designated as the Empress of India at a durbar (royal court) held at Delhi in 1877. Viceroy, the crown’s representative in India, became the chief executive-in-charge, while a secretary of state for India, a member of the British cabinet, exercised control over Indian affairs. A separate office called the India Office, headed by the secretary of state, was created in London to exclusively oversee the Indian affairs, while the Colonial Office managed the rest of the British Empire. The British-Indian army was reorganized and control over India was established through direct or indirect rule. The territories ruled directly by the British came to be known as British India. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Y1 Q2 9-12.Pdf

Balagokulam Syllabus April - June Age Group : 9 to 12 Gokulam is the place where Lord Krishna‛s magical days of childhood were spent. It was here that his divine powers came to light. Every child has that spark of divinity within. Bala- Gokulam is a forum for children to discover and manifest that divinity. It will enable Hindu children in US to appreciate their cultural roots and learn Hindu values in an enjoyable manner. This is done through weekly gatherings and planned activities which include games, yoga, stories, shlokas, bhajan, arts and crafts and much more...... Balagokulam is a program of Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) Table of Contents April Shloka / Subhashitam / Amrutvachan ....................................5 Geet ........................................................................................6 Yugadi ....................................................................................7 Stories of Dr. Hedgewar .......................................................10 The Hindu Calendar .............................................................13 Exercise ................................................................................16 Project / Workshop - Art of Story Telling ............................19 May Shloka / Subhashitam / Amrutvachan ..................................20 Geet ......................................................................................21 Symbols in Hinduism ...........................................................22 The Life of Buddha ..............................................................26 -

In Bad Faith? British Charity and Hindu Extremism

“I recognized two people pulling away my daughter Shabana. My daughter was screaming in pain asking the men to leave her alone. My mind was seething with fear and fury. I could do nothing to help my daughter from being assaulted sexually and tortured to death. My daughter was like a flower, still to see life.Why did they have to do this to her? What kind of men are these? The monsters tore my beloved daughter to pieces.” Medina Mustafa Ismail Sheikh, then in Kalol refugee camp, Panchmahals District, Gujarat This report is dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of Indians who have lost their homes, their loved ones or their lives because of the politics of hatred.We stand by those in India struggling for justice, and for a secular, democratic and tolerant future. 2 IN BAD FAITH? BRITISH CHARITY AND HINDU EXTREMISM INFORMATION FOR READERS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A separate report summary is available from Any final conclusions of fact or expressions of www.awaazsaw.org. Each section of this opinion are the responsibility of Awaaz – South report also begins with a summary of main Asia Watch Limited alone. Awaaz – South Asia findings. Watch would like to thank numerous individuals and organizations in the UK, India and the US for Section 1 provides brief information on advice and assistance in the preparation of this Hindutva and shows Sewa International UK’s report. Awaaz – South Asia Watch would also like connections with the RSS. Readers familiar to acknowledge the insights of the report The with these areas can skip to: Foreign Exchange of Hate researched by groups in the US. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots Buddhism (Buddha) Followed by Hindūism (Kṛṣṇā) The religion of the Vedic period (also known as Vedism or Vedic Brahmanism or, in a context of Indian antiquity, simply Brahmanism[1]) is a historical predecessor of Hinduism.[2] Its liturgy is reflected in the Mantra portion of the four Vedas, which are compiled in Sanskrit. The religious practices centered on a clergy administering rites that often involved sacrifices. This mode of worship is largely unchanged today within Hinduism; however, only a small fraction of conservative Shrautins continue the tradition of oral recitation of hymns learned solely through the oral tradition. Texts dating to the Vedic period, composed in Vedic Sanskrit, are mainly the four Vedic Samhitas, but the Brahmanas, Aranyakas and some of the older Upanishads (Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Chāndogya, Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana) are also placed in this period. The Vedas record the liturgy connected with the rituals and sacrifices performed by the 16 or 17 shrauta priests and the purohitas. According to traditional views, the hymns of the Rigveda and other Vedic hymns were divinely revealed to the rishis, who were considered to be seers or "hearers" (shruti means "what is heard") of the Veda, rather than "authors". In addition the Vedas are said to be "apaurashaya", a Sanskrit word meaning uncreated by man and which further reveals their eternal non-changing status. The mode of worship was worship of the elements like fire and rivers, worship of heroic gods like Indra, chanting of hymns and performance of sacrifices. The priests performed the solemn rituals for the noblemen (Kshsatriya) and some wealthy Vaishyas. -

Times-NIE-Web-Ed-AUGUST 14-2021-Page3.Qxd

CELLULAR JAIL, ANDAMAN & BIRLA HOUSE: Birla House is a muse- NICOBAR ISLANDS: Also known as um dedicated to Mahatma Gandhi. It ‘Kala Pani’, the British used the is the location where Gandhi spent CELEBRATING FREEDOM jail to exile political prisoners at the last 144 days of his life and was SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, 2021 03 this colonial prison assassinated on January 30, 1948 CLICK HERE: PAGE 3 AND 4 Pre-Independence slogans and its relevance in India today Slogans raised by leaders during the freedom movement set the mood of the nation’s revolution for its independence. They epitomised the struggle and hopes of millions of Indians. Author and former ad guru ANUJA CHAUHAN revisits these powerful slogans and explains their history and relevance in a contemporary India SATYAMEV JAYATE QUIT INDIA LIKE SWARAJ, KHADI IS (Truth alone triumphs) HISTORY: This slogan is widely associ- OUR BIRTH-RIGHT ated with Mahatma Gandhi (what he HISTORY: Inscribed at the base of started was the Quit India Movement India’s national emblem, this phrase is from August 8, 1942, in Bombay (then), a mantra from the ancient Indian scr- but the term ‘Quit India’ was actually ipture, ‘Mundaka Upanishad’, which coined by a lesser-known hero of was popularised by freedom fighter India’s freedom struggle – Yusuf Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya during Meherally. He had published a booklet India’s freedom movement. titled ‘Quit India’ (sold in weeks) and got over a thousand ‘Quit India’ badges to give life to the slogan that Gandhi also started using and popularised. ‘YOUNGSTERS, DON’T QUIT INDIA’: Quit India was a powerful slogan and HISTORY: Mahatma Gandhi’s call to as a slogan) was written by Urdu the jingle of an epic movement meant use khadi became a movement for poet Muhammad Iqbal in 1904 for to drive the British away from our the indigenous swadeshi (Indian) children. -

Some Questions Concerning the Ugc Course in Astrology

SOME QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE UGC COURSE IN ASTROLOGY Kushal Siddhanta 18 AUGUST 2001. Dr. Murali Manohar cient Indian astronomer Varahamihira who Joshi, the present Union HRD Minister and in the sixth century AD spoke about the a former professor of physics in the Alla- earth's rotation.” Citing another fact in sup- habad University, was invited to the IIT, port of introducing astrology as a university Kharagpur, as the chief guest at an open- course, he said, 16 universities of the coun- ing function organized on the occasion of try had already been offering astrology as its fiftieth foundation anniversary. The a subject in various forms. So his govern- West Bengal Chief Minister Mr. Buddhadeb ment is doing nothing new. People should Bhattacharya was another guest. not oppose the astrology and other courses only on political reasons. There may be de- As expected, Mr. Bhattacharya in his bates and arguments over the issue. The speech indirectly criticized the policy of the Government, he assured all, was ready to Union Government to introduce worn out hear. So on and so forth. subjects like astrology, paurohitya, vas- tushastra, yoga and human consciousness, It all had started when the UGC issued a etc., in the universities through the Univer- circular on 23 February 2001 with a pro- sity Grant Commission (UGC). Dr. Joshi posal to all the universities of the country in his address, however, did not go into to introduce UG and PG courses as well the trouble of explaining why his depart- as doctoral researches in Vedic Astrology ment was so keen on funding these anti- which it later renamed in parenthesis as quated subjects in the universities in spite Jyotirvigyan (astronomy).