State Aid and the Single Market Abbreviations and Symbols Used

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amtsblatt 10-2018

Gemeinde-Nachrichten Amtsblatt der Gemeinde Unterwellenborn mit den Ortsteilen Birkigt, Bucha, Dorfkulm, Goßwitz, Kamsdorf, Könitz, Langenschade, Lausnitz, Oberwellenborn, Unterwellenborn Nr. 10 Samstag, 1. September 2018 13. Jahrgang Ein Tag �ür die ganze Familie mit Einblicken in die Geologie unserer Region und tollen Mitmachaktionen Sa., 8.9.2018 von 10.00 bis 17.00 Uhr Die siebte Geotour beginnt gleichzeitig an verschiedenen Veranstaltungsorten mit Führungen. Die Anreise ist per Bahn möglich (Strecke Saalfeld-Gera), Bahnhof Könitz. Eintritt: 2,00 €, Kinder bis 14 Jahre frei. Parkplätze sind an den einzelnen Veranstaltungsorten vorhanden. Festgelände am Parkpla / Kinderspielpla, Friedrich-Ebert-Straße Veranstalter: Bergbau- und Heimatmuseum Köni Geologie und Geschichte unter Tage erleben - Öffnung der über 300-jährigen „Höhler“ im Zechsteinriff unter dem Schlossberg Köni • Führungen gewähren Ihnen Einblicke ins Innere des Zechsteinriffs und geben geschichtliche Aufschlüsse zur Anlage der Felsenkeller und Gebäude • 10.00 - 12.00 Uhr und 14.00 - 16.00 Uhr Führungen im Bergbau- und Heimatmuseum sowie Mitmach- und Beschäftigungsangebote im Museumsgarten: • Eröffnung 10.00 Uhr • 14.00 Uhr Lesung für Groß und Klein • „Als Köni am Meer lag“ (Präsentation) Naturpark Thüringer Schiefergebirge/Obere Saale • Mineralienfachgruppe Rudolstadt • Quiz für Kinder und Erwachsene • Bastelangebote • Für das leibliche Wohl wird gesorgt. Ab 10.00 Uhr Führungen im Steine-Zimmer Köni (gegenüber Museum) mit Mineralienverkauf. Kindertanzfest der Kindertanzgruppe der Feuerwehr Köni • 14.00 Uhr beginnt das Tanzfest an der Feuerwehr in der Herthum-Straße • 17.30 Uhr Wettbewerb der Tanzgruppen • Rost brennt, Kaffee und Kuchen, Getränkeversorgung durch Brauhaus Saalfeld Schloss Köni • Führungen im Schloss ab 10.00 Uhr Kamsdorf, Kirche Peter und Paul • Garten der Labyrinthe geöffnet Großtagebau Kamsdorf GmbH Aktivitäten zum Tag des offenen Steinbruchs am 08.09.2018 • Führungen im Tagebau mit Shuttlebus • Naturschu im Steinbruch (Stand des UVMB, Betreuung durch den Biologen, Herrn Fox, evtl. -

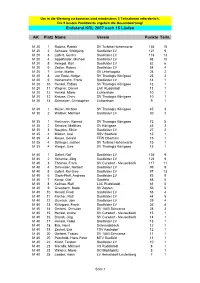

Endstand Kreisrangliste 2007

Um in die Wertung zu kommen sind mindestens 3 Teilnahmen erforderlich. Die 9 besten Punktwerte ergeben die Gesamtwertung! Endstand KRL 2007 nach 15 Läufen AK Platz Name Verein Punkte Teiln. M 20 1 Ratzka, Patrick SV Turbine Hohenwarte 135 15 M 20 2 Schwarz, Wolfgang Saalfelder LV 121 9 M 20 3 Lipfert, Günter Saalfelder LV 118 13 M 20 4 Appelfelder, Michael Saalfelder LV 98 10 M 20 5 Hempel, Karl Saalfelder LV 82 6 M 20 6 Zedler, Robert Saalfelder LV 54 4 M 20 7 Linke, Martin SV Unterloquitz 24 2 M 20 8 von Ende, Holger SV Thuringia Königsee 23 2 M 20 9 Heinemann, Frank Saalfelder LV 14 1 M 20 10 Henkel, Tobias SV Thuringia Königsee 13 1 M 20 11 Wagner, Daniel LAC Rudolstadt 11 1 M 20 12 Henkel, Mario Lichtenhain 10 1 M 20 12 Krause, Chris SV Thuringia Königsee 10 1 M 20 14 Schneider, Christopher Lichtenhain 9 1 M 30 1 Müller, Michael SV Thuringia Königsee 45 3 M 30 2 Walther, Michael Saalfelder LV 30 2 M 35 1 Hartmann, Konrad SV Thuringia Königsee 72 5 M 35 2 Scholze, Matthias SV Königsee 45 3 M 35 3 Naujoks, Silvio Saalfelder LV 27 2 M 35 4 Mädler, Axel SSV Saalfeld 15 1 M 35 4 Meyer, Gerald FFW Oberhain 15 1 M 35 4 Schlegel, Jochen SV Turbine Hohenwarte 15 1 M 35 4 Weigel, Uwe SV Thuringia Königsee 15 1 M 40 1 Gabel, Ralf Saalfelder LV 135 9 M 40 2 Schenke, Jörg Saalfelder LV 124 9 M 40 3 Thomas, Frank SV Cursdorf - Meuselbach 117 11 M 40 4 Schneider, Norbert Saalfelder LV 99 9 M 40 5 Lipfert, Kai-Uwe Saalfelder LV 97 13 M 40 6 Gloth-Pfaff, Andreas Saalfelder LV 83 9 M 40 7 Kamp, Olaf Saalfeld 68 5 M 40 8 Keilhau, Ralf LAC Rudolstadt -

Nr. 1 Vom 30.01.2021

Gemeinde-Nachrichten Amtsblatt der Gemeinde Unterwellenborn POSTAKTUELL – Sämtliche Haushalte – Sämtliche POSTAKTUELL mit den Ortsteilen Birkigt, Bucha, Dorfkulm, Goßwitz, Kamsdorf, Könitz, Langenschade, Lausnitz, Oberwellenborn, Unterwellenborn Nr. 1 Samstag, 30. Januar 2021 16. Jahrgang Gemeinde Unterwellenborn - 2 - Samstag, den 30. Januar 2021 Öffnungszeiten der Verwaltung Sprechzeiten der Ortsteilbürgermeister der Gemeinde Unterwellenborn OT Birkigt Herr Mike Oechsner Ernst-Thälmann-Straße 19 nach telefonischer Vereinbarung unter: 0152 24480133 Dienstag 08.30 Uhr bis 12.00 Uhr OT Bucha 13.30 Uhr bis 17.45 Uhr Herr Bernd Bloß Donnerstag 08.30 Uhr bis 12.00 Uhr nach telefonischer Vereinbarung unter: 0170 4122856 13.30 Uhr bis 15.45 Uhr E-Mail: [email protected] Montag, Mittwoch, Freitag nach Vereinbarung OT Dorfkulm Sprechzeiten der Bürgermeisterin Herr Christian Haun nach telefonischer Vereinbarung unter: 03671 6731-11 nach telefonischer Vereinbarung unter: 03671 615606 Sprechzeiten des Kontaktbereichsbeamten OT Goßwitz der PI Saalfeld Herr Bernd Bloß Dienstag 15.00 Uhr bis 17.00 Uhr nach telefonischer Vereinbarung unter: 0170 4122856 Telefon: 03671 459635 E-Mail: [email protected] bzw. über PI Saalfeld, Telefon 03671 56-0 OT Kamsdorf Sprechzeiten der Schiedsstelle Herr Thomas Kuhn Schiedsfrau: Ines Greiling jeden 1. und 3. Dienstag im Monat von 17.00 bis 18.00 Uhr Dienstag zwischen 19.00 Uhr und 20.00 Uhr Gebäude: Zollhäuser Straße 28, OT Kamsdorf nach telefonischer Vereinbarung unter: 0160 96085875 bzw. nach telef. Vereinbarung unter: 0152 28002080 E-Mail: [email protected] Sprechzeiten des Revierförsters Revierleiter: Herr Schröter OT Könitz jeden 2. und 4. Dienstag im Monat 16.00 Uhr bis 17.30 Uhr Frau Silke Gollnick Telefon 0172 3480321 jeden 2. -

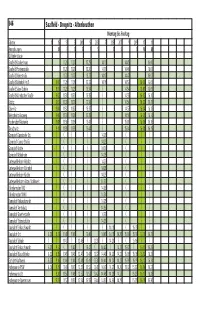

546 Saalfeld - Drognitz - Altenbeuthen Montag Bis Freitag Fahrtnr

546 Saalfeld - Drognitz - Altenbeuthen Montag bis Freitag Fahrtnr. 1 15 13 3 201 5 203 7 205 207 9 209 17 11 Anmerkungen M F S S F S S S S M 1 Gültigkeitstage Saalfeld Krankenhaus 11. 20 11. 20 13.25 14.10 14.45 16.00 Saalfeld Pfortenstraße 11. 21 11. 21 13.26 14.11 14.46 16.01 Saalfeld Dürerstraße 11. 22 11. 22 13.27 14.12 14.47 16.02 Saalfeld Bahnhof Hst.5 9.00 11. 28 11. 28 13.33 14.18 14.53 16.00 16.08 Saalfeld Sabel-Schule 9.01 11. 29 11. 29 13.34 {_ 14.54 16.01 16.09 Saalfeld Kulmbacher Straße 9.02 11. 3 0 11. 3 0 13.35 {_ 14.55 16.02 16.10 Köditz 9.03 11. 31 11. 31 13.36 {_ 14.56 16.03 16.11 Obernitz 9.04 11. 32 11. 32 13.37 {_ 14.57 16.04 16.12 Weischwitz Abzweig 9.06 11. 34 11. 34 13.39 {_ 14.59 16.05 16.14 Fischersdorf Abzweig 9.08 11. 3 6 11. 3 6 13.41 {_ 15.01 16.06 16.16 Tauschwitz 9.11 11. 39 11. 39 13.44 {_ 15.04 16.08 16.19 Gorndorf Gorndorfer Str. {_ {_ {_ {_ 14.21 {_ {_ {_ Gorndorf Geraer Straße {_ {_ {_ {_ 14.23 {_ {_ {_ Gorndorf Kirche {_ {_ {_ {_ 14.24 {_ {_ {_ Gorndorf Wohnheim {_ {_ {_ {_ 14.25 {_ {_ {_ Unterwellenborn Röblitz {_ {_ {_ {_ 14.27 {_ {_ {_ Unterwellenborn Bahnhof {_ {_ {_ {_ 14.28 {_ {_ {_ Unterwellenborn Kirche {_ {_ {_ {_ 14.29 {_ {_ {_ Unterwellenborn Abzw. -

Regionales Flächenmanagement Im Städtedreieck Am Saalebogen – Konzeption, Handhabe Und Weiterentwicklung –

Technische Universität Dresden Fakultät für Architektur Institut für Städtebau und Regionalplanung Dissertation zum Thema: Regionales Flächenmanagement im Städtedreieck am Saalebogen – Konzeption, Handhabe und Weiterentwicklung – Vorgelegt von: Robert Koch Referenten: Prof. Dr. Rainer Winkel Prof. Dr. Rainer Danielzyk Prof. Dr. Gerold Kind Verzeichnisse i Inhaltsverzeichnis Tabellenverzeichnis................................................................................................................................iv Abbildungsverzeichnis.............................................................................................................................v Abkürzungsverzeichnis...........................................................................................................................vi Vorwort und Danksagung.......................................................................................................................ix 1 EINFÜHRUNG: THEMATIK, ZIELSETZUNG UND VORGEHENSWEISE........................................................................................................1 2 DAS SELBSTVERSTÄNDNIS DER RAUMPLANUNG: ZWISCHEN PLANUNG UND ENTWICKLUNG ...............................................................................................................9 2.1 DIE ENTWICKLUNG EINER UMFASSENDEN RAUMPLANUNG IN DEUTSCHLAND ................10 2.2 AKTUELLE RAHMENBEDINGUNGEN UND REAKTION DER RAUMPLANUNG DARAUF ..........14 2.3 EINE ‚NEUE’ PLANUNGSKULTUR..................................................................................17 -

Industrie- Und Gewerbegebiet „Maxhütte” Unterwellenborn

Industrie- und Gewerbegebiet „Maxhütte” Unterwellenborn Ein Standortangebot der Landesentwicklungsgesellschaft Thüringen mbH Industrie- und Gewerbegebiet „Maxhütte” Unterwellenborn Inhalt 1. Der Standort 3 1.1Lage und Verkehrsanbindung 4 1.2Flächen und Nutzung 5 1.3 Ansprechpartner für Mietpreise, Medienversorgung und Steuersätze 6 1.4 Arbeitskräfte 7 1.5Unternehmen am Standort 8 2. Das Umfeld 10 3. LEG Thüringen - Ihr Ansprechpartner 11 Landesentwicklungsgesellschaft Thüringen mbH Abteilung Standortmanagement Industrie, Gewerbe und Konversion Mainzerhofstraße 12, 99084 Erfurt E-Mail [email protected] Internet www.leg-thueringen.de Ihr Ansprechpartner: Bernd Peupelmann Telefon 0361 5603-170 Fax 0361 5603-335 E-Mail [email protected] Stand: Februar 2010 Industrie- und Gewerbegebiet „Maxhütte” Unterwellenborn 1 Standort Seit mehr als 130 Jahren wird in Unterwellenborn Stahlproduktion betrieben. 1992 wurde die Stahlwerk Thüringen GmbH gegründet, die heute den industriellen Kernbereich des Standortes bildet und zum Stahlproduzenten der „Grupo Alfonso Gallardo” gehört. Diesen Standort zu erhalten und in ein modernes und umweltfreundliches Industrie- und Gewerbegebiet umzuwandeln, ist das Ziel der Landesentwicklungsgesellschaft Thüringen. Neue Arbeitsplätze, besonders im produzierenden Bereich, zu schaffen und ein hohes Maß an Wertschöpfung, ist die Aufgabe der LEG im Rahmen der Infrastrukturentwicklung. Seit der Übernahme des Gebietes im Jahre 1993 wurden: • ein neues Straßennetz mit der Bundesfernstraße 281 und 13 Brückenbauwerken geschaffen, • ein komfortabler Eisenbahnanschluss für das Stahlwerk errichtet, • die Ver- und Entsorgung (Gas, Strom, Telekommunikation, Wasser/Abwasser) auf ca. 260 ha neu geordnet und zahlreiche Unternehmen angesiedelt. Der Standort ist heute ein umweltfreundliches Industrie- und Gewerbegebiet. Die Erschließ- ungsmaßnahmen beinhalten auch die Erweiterung der Halde und deren Nachnutzung. Im Jahr 2000 wurden die Erschließungsstraßen den Gemeinden Unterwellenborn, Kamsdorf und der Stadt Saalfeld übergeben. -

Amtsblatt 07/2020

Gemeinsames Amts- und Mitteilungsblatt des Landkreises Saalfeld Rudolstadt, der Städte Saalfeld/Saale, Rudolstadt und Bad Blankenburg 07/20 Amtsblatt: 27. JAHRGANG 16. April 2020 In Reschwitz und Obernitz haben die Arbeiten für die neue Radwege- Kürzlich besuchte Landrat Marko Wolfram die Schneiderei des Thea- brücke über die Saale begonnen. Inzwischen sind vier Gruben für die ters Rudolstadt, um sich bei Josefine Schorcht (li.) und Doreen Freyer Betonfundamente mit einer Drainageschicht ausgestattet. Die beiden für die Aktion zum Nähen von Mundbedeckungen zu bedanken. „Das Gruben in Obernitz haben bereits ihre Säuberungsschicht aus Beton. ist ein großartiges Zeichen der Solidarität“, sagte Wolfram. Das Thea- Auf der Reschwitzer Seite wurde am 1. April die vierte Säuberungs- ter hatte mit der Aktion begonnen, weil der Spielbetrieb derzeit ruhen schicht ausgebracht. Das Landratsamt ist Bauherr der Maßnahme. muss und gleichzeitig die Nachfrage nach Gesichtsmasken sehr hoch Im Rahmen der Gemeinschaftsaufgabe zur Verbesserung der regio- ist. Die durch die Theater-Schneiderei angefertigten Masken können nalen Wirtschaftsstruktur fördert der Freistaat 90 Prozent der förder- vor allem im nicht-medizinischen Bereich eingesetzt werden, etwa für fähigen Gesamtkosten. Rund zwei Millionen Euro kostet die Brücke. Busfahrer der Kombus, beim Einkaufen in Geschäften oder in Verwal- Die Stadt Saalfeld finanziert den Eigenanteil und übernimmt nach tungen. Dort müssen sie weniger dem Schutz des Trägers dienen, als Abschluss der Bauarbeiten die Brücke in ihr Eigentum. vor allem dessen Gegenüber. Weitere Freiwillige haben sich der Aktion (Foto: Martin Modes) angeschlossen. (Foto: Peter Lahann) (Foto: Peter Lahann) Mit der Aktion „Wir bleiben für euch hier! Bleibt ihr für uns zu Hause Am Kulturpalast in Unterwellenborn laufen die Arbeiten zur Dachsa- und gesund!“ senden die Mitarbeiter des OP-Teams der Thüringen-Kli- nierung. -

Aach Aach, Stadt Aachen, Stadt Aalen, Stadt Aarbergen Aasbüttel

Die im Folgenden aufgeführten Gemeinden (oder entsprechenden kommunalen Verwaltungen) sind mit dem jeweiligen teilnehmenden Land (Bundesministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur) als die Liste der in Betracht kommenden Einrichtungen vereinbart worden und können sich für das WiFi4EU-Programm bewerben. „Gemeindeverbände“, sofern sie für jedes Land festgelegt und nachstehend aufgeführt sind, können sich im Namen ihrer Mitgliedsgemeinden registrieren, müssen den endgültigen Antrag jedoch für jede Gemeinde in ihrer Registrierung einzeln online einreichen. Jeder Gutschein wird an eine einzelne Gemeinde als Antragsteller vergeben. Während der gesamten Laufzeit der Initiative kann jede Gemeinde nur einen einzigen Gutschein einsetzen. Daher dürfen Gemeinden, die im Rahmen einer Aufforderung für einen Gutschein ausgewählt wurden, bei weiteren Aufforderungen nicht mehr mitmachen, wohingegen sich Gemeinden, die einen Antrag gestellt, aber keinen Gutschein erhalten haben, in einer späteren Runde wieder bewerben können. Gemeinden (oder entsprechende kommunale Verwaltungen) Aach Adelshofen (Fürstenfeldbruck) Aach, Stadt Adelshofen (Ansbach, Landkreis) Aachen, Stadt Adelsried Aalen, Stadt Adelzhausen Aarbergen Adenau, Stadt Aasbüttel Adenbach Abenberg, St Adenbüttel Abensberg, St Adendorf Abentheuer Adlkofen Absberg, M Admannshagen-Bargeshagen Abstatt Adorf/Vogtl., Stadt Abtsbessingen Aebtissinwisch Abtsgmünd Aerzen, Flecken Abtsteinach Affalterbach Abtswind, M Affing Abtweiler Affinghausen Achberg Affler Achern, Stadt Agathenburg Achim, Stadt -

Planungszeitraum 2008 - 2013

Sport- und Spielstättenrahmenleitplan des Landkreises Saalfeld-Rudolstadt Planungszeitraum 2008 - 2013 2. Fortschreibung Stand: Juni 2008 I N H A L T S V E R Z E I C H N I S Seite 1. Erläuterungen zur Fortschreibung 1 2. Aktualisierung statistischer Grundlagen 2 3. Entwicklungen in den Städten; Gemeinden und Verwaltungsgemeinschaften 3.1. Städte und Gemeinden ohne Anschluss an Verwaltungs- gemeinschaften Stadt Saalfeld (einschl. Arnsgereuth) 4 Stadt Rudolstadt 11 Stadt Bad Blankenburg 16 Stadt Königsee 18 Stadt Gräfenthal 20 Stadt Remda - Teichel 22 Stadt Leutenberg 24 Gemeinde Kamsdorf 26 Gemeinde Kaulsdorf (einschl. Altenbeuthen, Drognitz, Hohenwarte) 27 Gemeinde Rottenbach 29 Gemeinde Saalfelder Höhe 30 Gemeinde Uhlstädt – Kirchhasel 32 Gemeinde Unterwellenborn 34 3.2. Verwaltungsgemeinschaften VG Mittleres Schwarzatal (Sitz Sitzendorf) 36 VG Lichte / Piesau / Schmiedefeld (Sitz Lichte) 38 VG Bergbahnregion / Schwarzatal (Sitz Oberweißbach) 40 VG Probstzella - Lehesten - Marktgölitz (Sitz Probstzella) 42 4. Entwicklung im Bäderwesen Bäder im Landkreis Saalfeld-Rudolstadt 44 (Auswertung der Bäderstudie des Landes 2005) 5. Dringlichkeitsliste zum Abbau des Fehlbedarfes 47 6. Fortschreibung 49 Anlagen: Bevölkerungsentwicklung im Landkreis 2001 – 2006 und Prognose bis 2020 (Auszug aus dem Sozialstrukturatlas Landkreis Saalfeld-Rudolstadt 2007) Bedarfsrichtwerte gemäß Thüringer Sportstättenplanungsverordnung 1 1. Erläuterungen zur Fortschreibung Die Fortschreibung von Sport- und Spielstättenleitplänen ist in der Thüringer Sportstätten- planungsverordnung (ThürSportPlVO § 3 Abs. 4) festgeschrieben. Demnach sind diese bei Bedarf spätestens alle 5 Jahre zu überprüfen und ggf. fortzuschreiben. Der Kreistag des Landkreises Saalfeld-Rudolstadt hat am 23. März 2003 die erste Fort- schreibung zum Sport- und Spielstättenrahmenleitplan des Landkreises Saalfeld-Rudolstadt beschlossen. Wesentlicher Bestandteil der ersten Fortschreibung ist die Dringlichkeitsliste zum Abbau des Fehlbedarfes an sportlicher Nutzfläche. -

Amtsblatt 02-2018

Gemeinde-Nachrichten Amtsblatt der Gemeinde Unterwellenborn mit den Ortsteilen Birkigt, Bucha, Dorfkulm, Goßwitz, Könitz, Langenschade, Lausnitz, Oberwellenborn, Unterwellenborn Nr. 2 Samstag, 3. Februar 2018 13. Jahrgang Öffnungszeiten der Verwaltung Sprechzeiten der der Gemeinde Unterwellenborn Ortsteilbürgermeister Dienstag 08.30 Uhr bis 12.00 Uhr OT Birkigt Sprechzeiten des Ortsteilbürgermeisters Herrn Mike Oechsner 13.30 Uhr bis 17.45 Uhr nach telefonischer Vereinbarung über Donnerstag 08.30 Uhr bis 12.00 Uhr Telefon 036732 20963 oder 0152 24480133 13.30 Uhr bis 15.45 Uhr OT Bucha Montag, Mittwoch, Freitag nach Vereinbarung Sprechzeiten des Ortsteilbürgermeisters Herrn Bernd Bloß und Öff- nungszeiten der Bücherei Goßwitz–Bucha s. OT Goßwitz Sprechzeiten der Bürgermeisterin OT Dorfkulm Sprechzeiten des Ortsteilbürgermeisters Herrn Christian Haun nach Vereinbarung Telefon 03671 6731-0 nach telefonischer Vereinbarung über Telefon 03671 615606 OT Goßwitz Sprechzeiten des Kontaktbereichsbeamten der PI Saalfeld Sprechzeiten des Ortsteilbürgermeisters Herrn Bernd Bloß im Amt der Gemeindeverwaltung Unterwellenborn, Ernst-Thäl- Terminvereinbarungen bitte über Telefon 0170 4122856 mann-Straße 19 E-Mail [email protected] Dienstag 15.00 Uhr bis 17.00 Uhr Öffnungszeiten Bücherei Goßwitz–Bucha im Bürgerhaus „Schacht telefonisch erreichbar Telefon 03671 459635 Luise“ jeden 1. und 3. Montag im Monat von 15.00 Uhr bis 17.00 Uhr bzw. über PI Saalfeld Telefon 03671 560 OT Könitz bzw. in Kamsdorf Telefon 03671 613265 Sprechzeiten der Ortsteilbürgermeisterin -

Amtsblatt 13-2018

Gemeinde-Nachrichten Amtsblatt der Gemeinde Unterwellenborn mit den Ortsteilen Birkigt, Bucha, Dorfkulm, Goßwitz, Kamsdorf, Könitz, Langenschade, Lausnitz, Oberwellenborn, Unterwellenborn Nr. 13 Samstag, 1. Dezember 2018 13. Jahrgang Frohe Weihnachten Liebe Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner von Unterwellenborn, werte Leserinnen und Leser unseres Amtsblattes! Wieder neigt sich ein Jahr seinem Ende zu. Die dunkle blatt noch informativer gestalten. Zahlreiche Vereine, Jahreszeit hat sich breit gemacht nach einem langen, Verbände und Organisationen veröffentlichen bereits warmen Sommer. Der erste Schnee ist gefallen und die ihre Veranstaltungstipps. Nutzen Sie die Gelegenheit, Adventszeit steht vor der Tür. besuchen Sie die Veranstaltungen auch in den anderen Wir erleben die Weihnachtszeit als eine Zeit des Ortsteilen und kommen Sie miteinander ins Gespräch. Schenkens und Beschenktwerdens. Ich möchte Sie er- Genießen Sie die Zeit mit Familie und Freunden. muntern, nicht nur materielle Dinge zu verschenken. Danke an alle ehrenamtlichen Helfer, ansässige Firmen, Oft ist es Aufmerksamkeit, etwas Zeit, ein liebes Wort Ortsteilbürgermeister, Gemeinderats- und Ortsteil- oder ein Lächeln von Familienangehörigen, Freunden, ratsmitglieder für die geleistete Arbeit. Nachbarn oder Kollegen. Dies bedeutet mehr als der 5. Schal oder die 7. Pralinenschachtel. Ich wünsche Ihnen und Ihren Familien ein frohes und #T4Für Unterwellenborn und Kamsdorf ist die Neuglie- friedliches Weihnachtsfest voller herzlicher Momente, derung ein Geschenk. Eine starke Gemeinde mit -

Die Wunderkammer Heidecksburg Hat Jetzt Ihre Türen Geöffnet Ausstellung, Die 100 Jahre Schlossmuseum Heidecksburg Würdigt, Kann Bis 29

Gemeinsames Amts- und Mitteilungsblatt des Landkreises Saalfeld-Rudolstadt, der Städte Saalfeld/Saale, Rudolstadt und Bad Blankenburg 19/20 Amtsblatt: 27. JAHRGANG 29. Oktober 2020 Die Wunderkammer Heidecksburg hat jetzt ihre Türen geöffnet Ausstellung, die 100 Jahre Schlossmuseum Heidecksburg würdigt, kann bis 29. August 2021 besichtigt werden Eine Zeitachse mit Plakaten aus 100 Jahren Museumsgeschichte empfängt die Besucher am Eingang. Über die Faszination der Gegenstände aus der Wunderkammer Heidecksburg drehte der MDR am Abend der Eröffnung für das Thüringenjounal und interviewte die stellvertretende Museumslei- tern Sabrina Lüderitz, die zusammen mit Dr. Lutz Unbehaun und Dr. Sandy Reinhardt die Ausstellung kuratiert hat. (Fotos: Martin Modes) Rudolstadt. Die Wunderkammer umsausstellung. An diesem Abend ckenden Ansichten und Objekten lungsgeschichte des Museums. Heidecksburg ist eröffnet! Un- war nicht nur die Jubiläumsaus- aus der Sammlung, die teilweise Ein Film des Deutschen Rund- ter dem Motto „Von A. Dürer bis stellung geöffnet – sämtliche zum ersten Mal gezeigt werden, funkarchivs über Ballett auf der Z. Katze“ wird das 100-jährige Bereiche des Thüringer Landes- gehört ein Gemälde von Fürst Heidecksburg setzt die Zeitreise in Bestehen des Schlossmuseums museums Heidecksburg konnten Günther Victor, des letzten Regen- bewegten Bildern fort. Und in der auf der Heidecksburg gewürdigt. vom Publikum erkundet werden, ten von Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, Ausstellung lädt eine ausführliche Es war die erste Ausstellungs- auch die aktuelle Sonderausstel- auf dessen Stiftung das Museum Zeitachse ein, Entwicklungen und eröffnung auf der Heidecksburg lung über die Ankerbausteine im auf der Heidecksburg zurückgeht. Wendepunkte der 100-jährigen seit den coronabedingten Ein- Graphik-Kabinett. Die Chance zur Unmittelbar neben seinem Bild Museumsgeschichte nachzuvoll- schränkungen im März.