Research Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference List

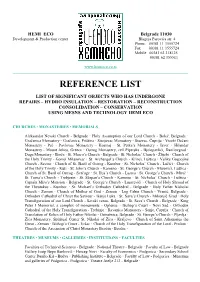

HEMI ECO Belgrade 11030 Development & Production center Blagoja Parovića str. 4 Phone 00381 11 3555724 Fax 00381 11 3555724 Mobile 00381 63 318125 00381 62 355511 www.hemieco.co.rs _______________________________________________________________________________________ REFERENCE LIST LIST OF SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS WHO HAS UNDERGONE REPAIRS – HYDRO INSULATION – RESTORATION – RECONSTRUCTION CONSOLIDATION – CONSERVATION USING MESNS AND TECHNOLOGY HEMI ECO CHURCHES • MONASTERIES • MEMORIALS Aleksandar Nevski Church - Belgrade · Holy Assumption of our Lord Church - Boleč, Belgrade · Gračanica Monastery - Gračanica, Priština · Sisojevac Monastery - Sisevac, Ćuprija · Visoki Dečani Monastery - Peć · Pavlovac Monastery - Kosmaj · St. Petka’s Monastery - Izvor · Hilandar Monastery - Mount Athos, Greece · Ostrog Monastery, cell Piperska - Bjelopavlići, Danilovgrad · Duga Monastery - Bioča · St. Marco’s Church - Belgrade · St. Nicholas’ Church - Žlijebi · Church of the Holy Trinity - Gornji Milanovac · St. Archangel’s Church - Klinci, Luštica · Velike Gospojine Church - Savine · Church of St. Basil of Ostrog - Kumbor · St. Nicholas’ Church - Lučići · Church of the Holy Trinity - Kuti · St. John’s Church - Kameno · St. George’s Church - Marovići, Luštica · Church of St. Basil of Ostrog - Svrčuge · St. Ilija’s Church - Lastva · St. George’s Church - Mirač · St. Toma’s Church - Trebjesin · St. Šćepan’s Church - Kameno · St. Nicholas’ Church - Luštica · Captain Miša’s Mansion - Belgrade · St. George’s Church - Lazarevići · Church of Holy Shroud of the Theotokos -

The Role of Churches and Religious Communities in Sustainable Peace Building in Southeastern Europe”

ROUND TABLE: “THE ROLE OF CHUrcHES AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES IN SUSTAINABLE PEACE BUILDING IN SOUTHEASTERN EUROPE” Under THE auSPICES OF: Mr. Terry Davis Secretary General of the Council of Europe Prof. Jean François Collange President of the Protestant Church of the Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine (ECAAL) President of the Council of the Union of Protestant Churches of Alsace and Lorraine President of the Conference of the Rhine Churches President of the Conference of the Protestant Federation in France Strasbourg, June 19th - 20th 2008 1 THE ROLE OF CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES IN SUSTAINABLE PEACE BUILDING PUBLISHER Association of Nongovernmental Organizations in SEE - CIVIS Kralja Milana 31/II, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia Tel: +381 11 3640 174 Fax: +381 11 3640 202 www.civis-see.org FOR PUBLISHER Maja BOBIć CHIEF EDITOR Mirjana PRLJević EDITOR Bojana Popović PROOFREADER Kate DEBUSSCHERE TRANSLATORS Marko NikoLIć Jelena Savić TECHNICAL EDITOR Marko Zakovski PREPRESS AND DESIGN Agency ZAKOVSKI DESIGN PRINTED BY FUTURA Mažuranićeva 46 21 131 Petrovaradin, Serbia PRINT RUN 1000 pcs YEAR August 2008. THE PUBLISHING OF THIS BOOK WAS supported BY Peace AND CRISES Management FOUndation LIST OF CONTEST INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 APPELLE DE STraSBOURG ..................................................................................................... 7 WELCOMING addrESSES ..................................................................................................... -

Church Newsletter

Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos Missionary Parish, Orange County, California CHURCH NEWSLETTER January – March 2010 Parish Center Location: 2148 Michelson Drive (Irvine Corporate Park), Irvine, CA 92612 Fr. Blasko Paraklis, Parish Priest, (949) 830-5480 Zika Tatalovic, Parish Board President, (714) 225-4409 Bishop of Nis Irinej elected as new Patriarch of Serbia In the early morning hours on January 22, 2010, His Eminence Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, locum tenens of the Patriarchate throne, served the Holy Hierarchal liturgy at the Cathedral church. His Eminence served with the concelebration of Bishops: Lukijan of Osijek Polje and Baranja, Jovan of Shumadia, Irinej of Australia and New Zealand, Vicar Bishop of Teodosije of Lipljan and Antonije of Moravica. After the Holy Liturgy Bishops gathered at the Patriarchate court. The session was preceded by consultations before the election procedure. At the Election assembly Bishop Lavrentije of Shabac presided, the oldest bishop in the ordination of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The Holy Assembly of Bishops has 44 members, and 34 bishops met the requirements to be nominated as the new Patriarch of Serbia. By the secret ballot bishops proposed candidates, out of which three bishops were on the shortlist, who received more than half of the votes of the members of the Election assembly. In the first round the candidate for Patriarch became the Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, in the second round the Bishop Irinej of Nis, and a third candidate was elected in the fourth round, and that was Bishop Irinej of Bachka. These three candidates have received more that a half votes during the four rounds of voting. -

“Thirty Years After Breakup of the SFRY: Modern Problems of Relations Between the Republics of the Former Yugoslavia”

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, INSTITUTE OF ECONOMICS “Thirty years after breakup of the SFRY: modern problems of relations between the republics of the former Yugoslavia” 15th independence anniversary of Montenegro: achievements and challenges Prof. dr Gordana Djurovic University of Monenegro 21 May 2021 1 An overview: from Doclea to the Kingdom of Montenegro (1) • During the Roman Empire, the territory of Montenegro was actually the territory of Duklja (DOCLEA). Doclea was originally the name of the Roman city on the site of modern Podgorica (Ribnica), built by Roman Emperor Diocletian, who hailed from this region of Roman Dalmatia. • With the arrival of the Slovenes in the 7th century, Christianity quickly gained primacy in this region. • Doclea (Duklja) gradually became a Principality (Knezevina - Arhontija) in the second part of the IX century. • The first known prince (knez-arhont) was Petar (971-990), (or Petrislav, according to Kingdom of Doclea by 1100, The Chronicle of the Priest of Dioclea or Duklja , Ljetopis popa Dukljanina, XIII century). In 1884 a during the rule of King Constantine Bodin lead stamp was found, on which was engraved in Greek "Petar prince of Doclea"; In that period, Doclea (Duklja) was a principality (Byzantine vassal), and Petar was a christianized Slav prince (before the beginning of the Slavic mission of Cirilo and Metodije in the second part of the IX century (V.Nikcevic, Crnogorski jezik, 1993). • VOJISLAVLJEVIĆ DYNASTY (971-1186) - The first ruler of the Duklja state was Duke Vladimir (990 – 1016.). His successor was duke Vojislav (1018-1043), who is considered the founder of Vojislavljević dynasty, the first Montenegrin dynasty. -

Authentic Getaway in Montenegro

YOUR ECOTOURISM ADVENTURE IN MONTENEGRO Authentic Getaway in Montenegro Tour description: Looking to avoid the cold and grey and enjoy an early spring? This 8-day, adventure itinerary will allow you to enjoy the best of Montenegro without the crowds or traffic. A perfect mix of bay side mountain trails, UNESCO Heritage sites and Old World charm topped off with lashings of Montenegrin gastronomic delights. Experience a way of life that is century’s old while enjoying a more modern level of comfort. You will enjoy local organic foods, visit forgotten places while enjoying a pleasant and sunny climate most of the time throughout the year! Whether you're with your family, a group of friends or your significant other, this trip is guaranteed to be a once in a lifetime journey! Tour details: Group: 3-10 people Departure dates: All year long Email: [email protected]; Website: www.montenegro-eco.com Mob|Viber|Whatsapp: +382(0)69 123 078 / +382(0)69 123 076 Adress: Moskovska 72 - 81000 Podgorica - Montenegro Our team speaks English, French, Italian and Montenegrin|Serbian|Bosnian|Croatian! YOUR ECOTOURISM ADVENTURE IN MONTENEGRO Full itinerary: DAY 1 – HERCEG NOVI, GATEWAY TO MONTENEGRO Transfer to your accommodation within a stone’s throw from the beautiful waters of the Gulf of Kotor. Spend the day exploring by foot the sites of this remarkable town: the Savina Monastery surrounded by thick Mediterranean vegetation, is one of the most beautiful parts of the northern Montenegrin coast. Don’t miss the charming Bellavista square in the old town, with the church of St Michael and Korača fountain, one of the last remaining examples of Turkish rule. -

A B C ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 185 Index A B Plaža Pizana 64 books, see also accommodation 18, 160-1, Balkan Flexipass 171 Pržno 56 literature history 144 see also individual Bar 78-81, 79 Queen’s Beach 73 locations & regions accommodation 78-9 Ričardova Glava 64 travel 136, 147, 150 activities 21-2, 27-8, see also drinking 80 Slovenska Plaža 65 border crossings 133, individual activities 168, 171 entertainment 80 Šušanj Beach 78 Ada Bojana 86-7 bridges events 78 Sveti Stefan 73 Adriatic coast 61-87, 63 Most na Moštanici 106 food 80 Tivat 52 accommodation 61 Tara Bridge 113 medical services 80 Velika Plaža climate 61, 62 budget 17 sights 78 (Big Beach) 86 food 61 Budva 12, 63-71, 65, 12 tourist office 80 Žanjic 55-6 highlights 63 accommodation 67-9 travel to/from 80-1 Žuta Plaža 43 history 62 activities 67 travel within 80-1 bears 90 travel seasons 61 drinking 70 Battle of Kosovo Polje 141 Bečići 71-2 travel to/from 62-3 events 67 Bay of Kotor 29, 32-60, Beška island 97 Adventure Race Montenegro food 69-70 33, 5 bicycle travel, see cycling 22, 114 accommodation 32 Bijelo Polje 118 nightlife 70 air travel 168-9 climate 32, 34 Biogradska Gora National Old Town 66 airlines 169 food 32 Park 11, 111-12, 157, 11 sights 64-67 airports 168-9 highlights 33 birdwatching 158 tours 67 animals, see individual Durmitor National Park travel to/from 70-1 species, wildlife history 33-4 113 bus travel archaeological sites, see travel seasons 32 Lake Šas 87 to/from Montenegro 170 ruins travel to/from 34 Lake Skadar National within Montenegro 172 architecture -

Ostrog Monastery Tour

Type: Pilgrimage, Nature, Scenic Drive, Charming Village Even if you are not terribly religious, you are certain to enjoy a tour of Ostrog Monastery. Amazing things have been known to happen here. On your tour to the Monastery, you will begin the 8 hour journey by passing through Risan. Risan is a small port town with only a couple of thousand inhabitants. Logs from the virgin forests in the Bijela Gora are exported to Italy today and this tourist destination offers beautiful beaches. Type: Pilgrimage, Nature, Scenic Drive, Charming Village Length: 8 Hours Walking: Medium Mobility: No wheelchairs Guide: Licensed Guide Language: English, Italian, French, German, Russian (other languages upon request) From Risan, you will travel up to the majestic Dinara Mountains and pass Slano Lake with its many small islands as well as the more shallow Krupac Lake. Your tour will then lead you to Niksic which is the second largest city in Montenegro after Podgorica. In Niksic, one of the most popular beers in the region is brewed, Niksicko beer is a local favourite. There are a few sites to see from here but the most exciting is the Ostrog Monastery. For your 110 km tour, you can experience much of Montenegro’s culture and its vast landscapes and natural beauty. The Monastery of Ostrog is a monastery of the Serb Orthodox Church located along the almost vertical cliff, high on the mountain call Ostroska greda (beams of Ostrog) with a view of the plains Bjelopavlici. It is in north part of Montenegro near Niksic, near village Bogetici. -

Balkan Traveller 巴尔干旅行者

No. 1 2018 BALKAN TRAVELLER 巴尔干旅行者 欢迎您来到 巴尔干半岛 国家描述和 该看什么 旅游杂志 Welcome to the Country descriptions and Travel journal through Balkans what to see Western Balkans Balkan Traveller /巴尔干旅行者 1 号, 2018 年 卢布尔亚那 / Ljubljana,2018 年 www.ceatm.org, [email protected], [email protected] SKYPE: CEATM d.o.o. QQ: 1712245775 总部 / Headquarters CEATM d.o.o. Dolga Poljana 57 SI 5271 Vipava, Slovenia 电 话 : +386 30 65 38 28 Andrej Raspor, CEO [email protected] 电 话 : +386 51 31 32 21 主编辑/ Editor in Chief: Andrej Raspor 编辑委员会 / Editorial Board: Tjaša Črv, Sanela Kšela 封面照片 / Cover photo: Tjaša Črv 别的照片 / Other photos: Luka Furjan, Tjaša Črv, Maša Egart, Tim Jeršič, Nika Črne, Pixabay (Creative Commons licence) 作家 / Authors: Andrej Raspor, Matej Krmelj, Sanela Kšela, Martina Kolak, Melisa Nikic, Danilo Bulatović, Frosina Ristovski, Stefan Eraković, Luka Furjan 翻译者/Translators: Seth Vid Peterson, Xiaoli Ye, Tina Žuber, Sanela Kšela, Martina Kolak, Melisa Nikic, Danilo Bulatović, Frosina Ristovski, Stefan Eraković, Luka Furjan 国际标准序列号 International Standard Serial Number (on line) ISSN 2630-2918 2 启事 / NOTICE 这本杂志来源于一个项目,名叫“探寻斯洛文尼亚的美”。 该杂志是由卢布尔雅那哲学院中文系学生合著。如有语法或用词不确,请大家多多谅解! This magazine was created within the project: Promotion of the beauty of Slovenia in the Chinese speaking area with innovative content. Articles in this magazine were written and translated by students of Sinology (Chinese) who are not native speakers. This means that there may be some errors in translations. Thank you for your understanding. Pedagoški mentorji / Pedagogical mentors: Sodelujoči študenti na projektu / Students working on the project: dr. Jaroslav Berce dr. Maja Veselič Tjaša Črv dr.Matevž Pogačnik Matej Krmelj Klemen Pečnik Seth Vid Peterson Xiaoli Ye DELOVNI MENTOR / Mentors from the business Tina Žuber sector: Maša Egart dr. -

Download Tour Dossier

Tour Notes Serbia Montenegro Croatia & Bosnia - Balkan Explorer Tour Duration – 15 Days Tour Rating Fitness ●●○○○ | Off the Beaten Track ●●●○○ | Culture ●●●●○ | History ●●●●○| Wildlife ●●●○○ Tour Pace Moderate Tour Highlights Durmitor National Park Ostrog Monastery Dubrovnik the Latin Bridge, site of the start of World War I Tour Map - Serbia Montenegro Croatia & Bosnia - Balkan Explorer Tour Essentials Accommodation: Mix of Comfortable hotels Included Meals: Daily breakfast (B), plus lunches (L) and dinners (D) as shown in the itinerary Group Size: Belgrade End Point: Belgrade Transport: Minibus Countries: Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina Balkan Explorer Visiting Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, this tour is a medley of former Yugoslav republics. Highlights include dynamic, modern European cities and coastal resorts, centres of conservative Orthodox Christian heritage, Sufi Islamic monasteries, pre-historic cultural centres, the point of origin for WW1, and a capital city that still bears the scars of Europe’s most recent war. Over two weeks the Balkans may or may not become easier to understand. However, cultural and ethnic differences which have over the centuries in turn forged alliances and catalysed conflict will become apparent. This is a holiday, with fine wines and excellent cuisine, but it’s also an exploration of human nature. Tour Itinerary Notes While our intention is to adhere to the day-by-day itinerary as printed below, a degree of flexibility is built in. Overnight stops may vary from those suggested and on occasions alternative accommodation, of a similar standard to that named below, will be used. Tour Guide Our guides are a key strength, chosen for their knowledge of and passion for the areas in which they work. -

The Orthodox Church in the 21St Century Radovan Bigović Predicted That Six Billion People Will Be Put Under Bio- Metrical Supervision by Year 2013

The Orthodox Church in the 21 st Century Radovan Bigović 1 Author Radovan Bigović Published by Foundation Konrad Adenauer Christian Cultural Center For the Publisher Henri G. Bohnet Editor Jelena Jablanov Maksimović, M.A. Reviewers Thomas Bremer , ThD ., professor of Ecumenical Theology and Peace Studies at the Faculty of Catholic Theology , Uni - versity of Münster, Germany Davor Džalto, Associate Professor and Program Director for Art History and Religious Studies The American University of Rome, PhD ., professor of History of Art and Theory of Creativity at the Faculty of Art , Universities of Niš and Kragujevac, Serbia Proof reader Ana Pantelić Translated into English by Petar Šerović Printed by EKOPRES, Zrenjanin Number of copies: 1000 in English Belgrade, 20 13 2 The Orthodox Church in the 21 st Century 3 4 Contents FOREWORD TO THE THIRD EDITION 7 THE CHURCH AND POSTMODERNISM 9 FAITH AND POSTMODERNISM 21 THE CHURCH, POLITICS, DEMOCRACY 27 The State-Nation Ideal 41 The Church and Democracy 46 ORTHODOXY AND DEMOCRACY 69 CHRISTIANITY AND POLITICS 81 THE CHURCH AND THE CIVIL SOCIETY 87 PRINCIPLES OF THE ORTHODOX CHURCH SOCIAL DOCTRINE 95 ORTHODOXY AND RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE 103 THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE NATION 117 ECUMENISM 121 CHRISTIANITY AND SCIENCE 125 CHRISTIAN CULTURE 131 INDEX 136 BIOGRAPHY 145 5 6 Foreword to the Third Edition The book that is before you is of great value for many a reason, but we will emphasize just two: the first is the theme it is dealing with, and the second is the uniqueness of the person whose pen served as the medium for the outpour of those very themes. -

Orthodox Christian Monasticism Part II

Orthodox Christian Monasticism Part II The innermost spiritual sense of Orthodox Monasticism is revealed in joyful mourning (gr. harmolipi). This paradoxical phrase denotes a spiritual state in hich a mon! in his prayer grieves for the sins of the orld at at the same time experiences the regenerating spritual joy of Christ"s forgiveness and resurrection. # mon! dies in order to live$ he forgets himself in order to find his real self in %od$ he &ecomes ignorant of orldly !no ledge in order to attain real spiritual isdom hich is given only to the hum&le ones. ('d.) %racanica Monastery$ (osovo)*er&ia$ ) a nun in prayer St Maximus the Confessor, in contrasting the monastic with the worldly life, observes that a layman's successes are a monk's failures, and vice versa: "The achievements of the worldly are failures for monks and the achievements of monks are failures for the worldly! "hen the monk is ex#osed to what the world sees as success$ wealth, fame, #ower, #leasure, good health and many children, he is destroyed! %nd when a worldly man finds himself in the state desired by monks$ #overty, humility, weakness, self restraint, mortifcation and suchlike, he considers it a disaster! &ndeed, in such des#air many may consider hanging themselves, and some have actually done so" '(! )f course the com#arison here is between the #erfect monk and the very worldly Christian! *owever, in more usual circumstances within the Church the same things will naturally function differently, but this difference could never reach diametrical o##osition! Thus -

Varna Nessebar

BALKANS A.B.A.T. Balkania Association of Balkan Alternative Tourism Str. Leninova No . 24 1000 – Skopje MACEDONIA Tel / fax : +389 2 32 23 101 Балканска Асоцијација за Алтернативен Туризам Балканија Text Fabio Cotifava, Emilia Kalaydjieva, Beatrice Cotifava Design Kalya Mondo srl, Alessandro Cotifava Photos GoBalkans ltd, Kalya Mondo srl Translation Chris Brewerton - Mantova (Italy) www.cbtraduzioni.it Printing Litocolor snc di Montanari e Rossetti - Guastalla di Reggio Emilia (Italy) Copyright GoBalkans ltd- December 2012 Privately printed edition BALKANIA is an Association of Balkan Alternative tourism which consists of eight member countries from the Balkans and Italy. Its activities include the execution of projects in order to promote the entire Balkan region as a tourist destination. In addition, its purpose is to restore the positive image of the Balkans in the public eye and promote their exceptional natural, histo- rical, cultural and anthropological heritage. The name of the Association, BALKANIA, sounds like a name of a new imaginary land on the territories represented by the hospitality of their population. One of the objectives of the project is to create a virtual geographic region that includes the territories and regions which are today identified with the term BALKANS. The efforts of the Association are aimed at channeling its energy to all forms that are alterna- tive to mass tourism, and which are in terms of the development of macro sectors identified as natural tourism, rural tourism and cultural tourism. BALKANIA is established on 24 .03.2009 in Skopje, in agreement with the Macedonian laws. It is formed by a group of partners from Macedonia, Bulgaria and Italy, with members from Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro , Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina ,Greece , Kosovo and Ma- cedonia .