Chapter 2: Christian Shrines and Muslim Pilgrims Joint Pilgrimages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

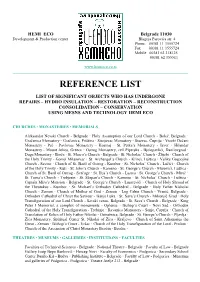

Reference List

HEMI ECO Belgrade 11030 Development & Production center Blagoja Parovića str. 4 Phone 00381 11 3555724 Fax 00381 11 3555724 Mobile 00381 63 318125 00381 62 355511 www.hemieco.co.rs _______________________________________________________________________________________ REFERENCE LIST LIST OF SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS WHO HAS UNDERGONE REPAIRS – HYDRO INSULATION – RESTORATION – RECONSTRUCTION CONSOLIDATION – CONSERVATION USING MESNS AND TECHNOLOGY HEMI ECO CHURCHES • MONASTERIES • MEMORIALS Aleksandar Nevski Church - Belgrade · Holy Assumption of our Lord Church - Boleč, Belgrade · Gračanica Monastery - Gračanica, Priština · Sisojevac Monastery - Sisevac, Ćuprija · Visoki Dečani Monastery - Peć · Pavlovac Monastery - Kosmaj · St. Petka’s Monastery - Izvor · Hilandar Monastery - Mount Athos, Greece · Ostrog Monastery, cell Piperska - Bjelopavlići, Danilovgrad · Duga Monastery - Bioča · St. Marco’s Church - Belgrade · St. Nicholas’ Church - Žlijebi · Church of the Holy Trinity - Gornji Milanovac · St. Archangel’s Church - Klinci, Luštica · Velike Gospojine Church - Savine · Church of St. Basil of Ostrog - Kumbor · St. Nicholas’ Church - Lučići · Church of the Holy Trinity - Kuti · St. John’s Church - Kameno · St. George’s Church - Marovići, Luštica · Church of St. Basil of Ostrog - Svrčuge · St. Ilija’s Church - Lastva · St. George’s Church - Mirač · St. Toma’s Church - Trebjesin · St. Šćepan’s Church - Kameno · St. Nicholas’ Church - Luštica · Captain Miša’s Mansion - Belgrade · St. George’s Church - Lazarevići · Church of Holy Shroud of the Theotokos -

Kosovo & Serbia

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 18 March 2004 KOSOVO & SERBIA: Churches & mosques destroyed amid inter-ethnic violence By Felix Corley, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org>, and <br> Branko Bjelajac, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> Large scale violence in Kosovo and Serbia before the 5th anniversary of Nato's bombing raids has seen many Serbian Orthodox churches and mosques attacked, amid disputed suggestions, including by an un-named UNMIK official, that the violence in Kosovo was planned as a "pogrom against Serbs: churches are on fire and people are being attacked for no other reason than their ethnic background", Forum 18 News Service has learnt. In the Serbian capital Belgrade and in the southern city of Nis, mobs set two mosques on fire despite the pleas of the Serbian Orthodox Church. In Belgrade, Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral personally pleaded with the mob and urged police and firefighters to react and preserve "what could be preserved". After initial hesitation for fear of the mob, firefighters and police did intervene, so the Belgrade mosque, which is "under state protection", was saved from complete destruction. In Kosovo since 1999, many attacks have been made on Orthodox shrines, without UNMIK, KFOR, or the mainly ethnically Albanian Kosovo Protection Service making any arrests of attackers. Some of the Serbian Orthodox Church's most revered shrines have been burnt amid the upsurge of inter-ethnic violence that erupted in Kosovo on 17 March, leaving at least 22 people dead and several hundred wounded. -

Cultural Heritage, Reconstruction and National Identity in Kosovo

1 DOI: 10.14324/111.444.amps.2013v3i1.001 Title: Identity and Conflict: Cultural Heritage, Reconstruction and National Identity in Kosovo Author: Anne-Françoise Morel Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 3, no.1. May 2013 Affiliation: Universiteit Gent Abstract: The year 1989 marked the six hundredth anniversary of the defeat of the Christian Prince of Serbia, Lazard I, at the hands of the Ottoman Empire in the “Valley of the Blackbirds,” Kosovo. On June 28, 1989, the very day of the battle's anniversary, thousands of Serbs gathered on the presumed historic battle field bearing nationalistic symbols and honoring the Serbian martyrs buried in Orthodox churches across the territory. They were there to hear a speech delivered by Slobodan Milosevic in which the then- president of the Socialist Republic of Serbia revived Lazard’s mythic battle and martyrdom. It was a symbolic act aimed at establishing a version of history that saw Kosovo as part of the Serbian nation. It marked the commencement of a violent process of subjugation that culminated in genocide. Fully integrated into the complex web of tragic violence that was to ensue was the targeting and destruction of the region’s architectural and cultural heritage. As with the peoples of the region, this heritage crossed geopolitical “boundaries.” Through the fluctuations of history, Kosovo's heritage had already become subject to divergent temporal, geographical, physical and even symbolical forces. During the war it was to become a focal point of clashes between these forces and, as Anthony D. Smith argues with regard to cultural heritage more generally, it would be seen as “a legacy belonging to the past of ‘the other,’” which, in times of conflict, opponents try “to damage or even deny.” Today, the scars of this conflict, its damage and its denial are still evident. -

TODAY We Are Celebrating Our Children's Slava SVETI SAVA

ST. ELIJAH SERBIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH 2200 Irwin Street, Aliquippa, PA 15001 Rev. Branislav Golic, Parish Priest e-mail: [email protected] Parish Office: 724-375-4074 webpage: stelijahaliquippa.com Center Office: 724-375-9894 JANUARY 26, 2020 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Saint Sava Born Prince Rastko Nemanjic, son of the Serbian ruler and founder of the Serbian medieval state Stefan Nemanja, St. Sava became the first Patriarch of Serbia (1219-1233) and is an important Saint in the Serbian Orthodox Church. As a young boy, Rastko left home to join the Orthodox monastic colony on Mount Athos and was given the name Sava. In 1197 his father, King Stefan Nemanja, joined him. In 1198 they moved to and restored the abandoned monastery Hilandar, which was at that time the center of Serbian Orthodox monastic life. St. Sava's father took the monastic vows under the name Simeon, and died in Hilandar on February 13, 1200. He is also canonized a saint of the Church. After his father's death, Sava retreated to an ascetic monastery in Kareya which he built himself in 1199. He also wrote the Kareya typicon both for Hilandar and for the monastery of ascetism. The last typicon is inscribed into the marble board at the ascetic monastery, which today also exists there. He stayed on Athos until the end of 1207, when he persuaded the Patriarch of Constantinople to elevate him to the position of first Serbian archbishop, thereby establishing the independence of the archbishopric of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the year 1219. Saint Sava is celebrated as the founder of the independent Serbian Orthodox Church and as the patron saint of education and medicine among Serbs. -

The Role of Churches and Religious Communities in Sustainable Peace Building in Southeastern Europe”

ROUND TABLE: “THE ROLE OF CHUrcHES AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES IN SUSTAINABLE PEACE BUILDING IN SOUTHEASTERN EUROPE” Under THE auSPICES OF: Mr. Terry Davis Secretary General of the Council of Europe Prof. Jean François Collange President of the Protestant Church of the Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine (ECAAL) President of the Council of the Union of Protestant Churches of Alsace and Lorraine President of the Conference of the Rhine Churches President of the Conference of the Protestant Federation in France Strasbourg, June 19th - 20th 2008 1 THE ROLE OF CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES IN SUSTAINABLE PEACE BUILDING PUBLISHER Association of Nongovernmental Organizations in SEE - CIVIS Kralja Milana 31/II, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia Tel: +381 11 3640 174 Fax: +381 11 3640 202 www.civis-see.org FOR PUBLISHER Maja BOBIć CHIEF EDITOR Mirjana PRLJević EDITOR Bojana Popović PROOFREADER Kate DEBUSSCHERE TRANSLATORS Marko NikoLIć Jelena Savić TECHNICAL EDITOR Marko Zakovski PREPRESS AND DESIGN Agency ZAKOVSKI DESIGN PRINTED BY FUTURA Mažuranićeva 46 21 131 Petrovaradin, Serbia PRINT RUN 1000 pcs YEAR August 2008. THE PUBLISHING OF THIS BOOK WAS supported BY Peace AND CRISES Management FOUndation LIST OF CONTEST INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 APPELLE DE STraSBOURG ..................................................................................................... 7 WELCOMING addrESSES ..................................................................................................... -

Church Newsletter

Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos Missionary Parish, Orange County, California CHURCH NEWSLETTER January – March 2010 Parish Center Location: 2148 Michelson Drive (Irvine Corporate Park), Irvine, CA 92612 Fr. Blasko Paraklis, Parish Priest, (949) 830-5480 Zika Tatalovic, Parish Board President, (714) 225-4409 Bishop of Nis Irinej elected as new Patriarch of Serbia In the early morning hours on January 22, 2010, His Eminence Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, locum tenens of the Patriarchate throne, served the Holy Hierarchal liturgy at the Cathedral church. His Eminence served with the concelebration of Bishops: Lukijan of Osijek Polje and Baranja, Jovan of Shumadia, Irinej of Australia and New Zealand, Vicar Bishop of Teodosije of Lipljan and Antonije of Moravica. After the Holy Liturgy Bishops gathered at the Patriarchate court. The session was preceded by consultations before the election procedure. At the Election assembly Bishop Lavrentije of Shabac presided, the oldest bishop in the ordination of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The Holy Assembly of Bishops has 44 members, and 34 bishops met the requirements to be nominated as the new Patriarch of Serbia. By the secret ballot bishops proposed candidates, out of which three bishops were on the shortlist, who received more than half of the votes of the members of the Election assembly. In the first round the candidate for Patriarch became the Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, in the second round the Bishop Irinej of Nis, and a third candidate was elected in the fourth round, and that was Bishop Irinej of Bachka. These three candidates have received more that a half votes during the four rounds of voting. -

Canon Law of Eastern Churches

KB- KBZ Religious Legal Systems KBR-KBX Law of Christian Denominations KBR History of Canon Law KBS Canon Law of Eastern Churches Class here works on Eastern canon law in general, and further, on the law governing the Orthodox Eastern Church, the East Syrian Churches, and the pre- Chalcedonean Churches For canon law of Eastern Rite Churches in Communion with the Holy See of Rome, see KBT Bibliography Including international and national bibliography 3 General bibliography 7 Personal bibliography. Writers on canon law. Canonists (Collective or individual) Periodicals, see KB46-67 (Christian legal periodicals) For periodicals (Collective and general), see BX100 For periodicals of a particular church, see that church in BX, e.g. BX120, Armenian Church For periodicals of the local government of a church, see that church in KBS Annuals. Yearbooks, see BX100 Official gazettes, see the particular church in KBS Official acts. Documents For acts and documents of a particular church, see that church in KBS, e.g. KBS465, Russian Orthodox Church Collections. Compilations. Selections For sources before 1054 (Great Schism), see KBR195+ For sources from ca.1054 on, see KBS270-300 For canonical collections of early councils and synods, both ecumenical/general and provincial, see KBR205+ For document collections of episcopal councils/synods and diocesan councils and synods (Collected and individual), see the church in KBS 30.5 Indexes. Registers. Digests 31 General and comprehensive) Including councils and synods 42 Decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts (Collective) Including related materials For decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts of a particular church, see that church in KBS Encyclopedias. -

“Thirty Years After Breakup of the SFRY: Modern Problems of Relations Between the Republics of the Former Yugoslavia”

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, INSTITUTE OF ECONOMICS “Thirty years after breakup of the SFRY: modern problems of relations between the republics of the former Yugoslavia” 15th independence anniversary of Montenegro: achievements and challenges Prof. dr Gordana Djurovic University of Monenegro 21 May 2021 1 An overview: from Doclea to the Kingdom of Montenegro (1) • During the Roman Empire, the territory of Montenegro was actually the territory of Duklja (DOCLEA). Doclea was originally the name of the Roman city on the site of modern Podgorica (Ribnica), built by Roman Emperor Diocletian, who hailed from this region of Roman Dalmatia. • With the arrival of the Slovenes in the 7th century, Christianity quickly gained primacy in this region. • Doclea (Duklja) gradually became a Principality (Knezevina - Arhontija) in the second part of the IX century. • The first known prince (knez-arhont) was Petar (971-990), (or Petrislav, according to Kingdom of Doclea by 1100, The Chronicle of the Priest of Dioclea or Duklja , Ljetopis popa Dukljanina, XIII century). In 1884 a during the rule of King Constantine Bodin lead stamp was found, on which was engraved in Greek "Petar prince of Doclea"; In that period, Doclea (Duklja) was a principality (Byzantine vassal), and Petar was a christianized Slav prince (before the beginning of the Slavic mission of Cirilo and Metodije in the second part of the IX century (V.Nikcevic, Crnogorski jezik, 1993). • VOJISLAVLJEVIĆ DYNASTY (971-1186) - The first ruler of the Duklja state was Duke Vladimir (990 – 1016.). His successor was duke Vojislav (1018-1043), who is considered the founder of Vojislavljević dynasty, the first Montenegrin dynasty. -

Authentic Getaway in Montenegro

YOUR ECOTOURISM ADVENTURE IN MONTENEGRO Authentic Getaway in Montenegro Tour description: Looking to avoid the cold and grey and enjoy an early spring? This 8-day, adventure itinerary will allow you to enjoy the best of Montenegro without the crowds or traffic. A perfect mix of bay side mountain trails, UNESCO Heritage sites and Old World charm topped off with lashings of Montenegrin gastronomic delights. Experience a way of life that is century’s old while enjoying a more modern level of comfort. You will enjoy local organic foods, visit forgotten places while enjoying a pleasant and sunny climate most of the time throughout the year! Whether you're with your family, a group of friends or your significant other, this trip is guaranteed to be a once in a lifetime journey! Tour details: Group: 3-10 people Departure dates: All year long Email: [email protected]; Website: www.montenegro-eco.com Mob|Viber|Whatsapp: +382(0)69 123 078 / +382(0)69 123 076 Adress: Moskovska 72 - 81000 Podgorica - Montenegro Our team speaks English, French, Italian and Montenegrin|Serbian|Bosnian|Croatian! YOUR ECOTOURISM ADVENTURE IN MONTENEGRO Full itinerary: DAY 1 – HERCEG NOVI, GATEWAY TO MONTENEGRO Transfer to your accommodation within a stone’s throw from the beautiful waters of the Gulf of Kotor. Spend the day exploring by foot the sites of this remarkable town: the Savina Monastery surrounded by thick Mediterranean vegetation, is one of the most beautiful parts of the northern Montenegrin coast. Don’t miss the charming Bellavista square in the old town, with the church of St Michael and Korača fountain, one of the last remaining examples of Turkish rule. -

Causes of the New Suffering of the Serbian Orthodox Church

UDC: 159.964.2(497) Review paper Recived: November 25, 2019. Acceptee: December 26, 2019 Coreresponding author: [email protected] THE UNREMOVED CONSEQUENCES OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR - CAUSES OF THE NEW SUFFERING OF THE SERBIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Jovan Janjić Faculty of Business Studies and Law. [email protected] Abstract: The non-elimination of the consequences of occupation in some parts of Yugoslavia in World War II, as well as preventing and obstructing from the Yugoslav state the elimination of the con- sequences of the war suffering of the Serbian Orthodox Church, will prevent and disable the Church in certain parts of its canonical territory and endanger, destroy and confiscate its property. This will then lead to a new suffering of the Serbian people, while putting the legal successor state of Yugoslavia to additional temptations. Non-return of property to the Serbian Church will be especially in favor of secessionist forces that threaten the territorial integrity of Serbia. Keywords: Serbian Orthodox Church, Yugoslavia, Serbia, occupation, property, usurpation INTRODUCTION The revolutionary communist authorities in Yugoslavia, in an effort to establish a social order by their ideological standards, relied on some of the consequences of the occupation in World War II. Especially in policymaking on the national issue and in relation to the Church. After taking power in the country - by conducting a revolution while waging a war for liberation from occupation - Yugoslavia’s new governing nomenclature, legitimized as such during the Second World War, was not content with establishing a state order, only on the basis of a single, exclusive ideology, but it penetrated the civilizational frameworks of state jurisdiction and went about creating the whole social order. -

The Serbian Orthodox Church and the New Serbian Identity

Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia THE SERBIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE NEW SERBIAN IDENTITY Belgrade, 2006 This Study is a part of a larger Project "Religion and Society," realized with the assistance of the Heinrich Böll Foundation Historical Confusion At the turn of the penultimate decade of the 20th century to the last, the world was shocked by the (out-of-court) pronouncement of the death verdict for an artist, that is, an author by the leader of a theocratic regime, on the grounds that his book insulted one religion or, to be more exact, Islam and all Muslims. Naturally, it is the question of the famous Rushdie affair. According to the leader of the Iranian revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini, the novel “Satanic Verses” by Salman Rushdie was blasphemous and the author deserved to be sentenced to death by a fatwa. This case - which has not been closed to this day - demonstrated in a radical way the seriousness and complexity of the challenge which is posed by the living political force of religious fundamentalism(s) to the global aspirations of the concept of liberal capitalist democracy, whose basic postulates are a secular state and secular society. The fall of the Berlin Wall that same year (1989) marked symbolically the end of an era in the international relations and the collapse of an ideological- political project. In other words, the circumstances that had a decisive influence on the formation of the Yugoslav and Serbian society in the post- World War II period were pushed into history. Time has told that the mentioned changes caused a tragic historical confusion in Yugoslavia and in Serbia, primarily due to the unreadiness of the Yugoslav and, in particular, Serbian elites to understand and adequately respond to the challenges of the new era.