Beaver County Natural Heritage Inventory Update 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

Sunol Wildflower Guide

Sunol Wildflowers A photographic guide to showy wildflowers of Sunol Regional Wilderness Sorted by Flower Color Photographs by Wilde Legard Botanist, East Bay Regional Park District Revision: February 23, 2007 More than 2,000 species of native and naturalized plants grow wild in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most are very difficult to identify without the help of good illustrations. This is designed to be a simple, color photo guide to help you identify some of these plants. The selection of showy wildflowers displayed in this guide is by no means complete. The intent is to expand the quality and quantity of photos over time. The revision date is shown on the cover and on the header of each photo page. A comprehensive plant list for this area (including the many species not found in this publication) can be downloaded at the East Bay Regional Park District’s wild plant download page at: http://www.ebparks.org. This guide is published electronically in Adobe Acrobat® format to accommodate these planned updates. You have permission to freely download and distribute, and print this pdf for individual use. You are not allowed to sell the electronic or printed versions. In this version of the guide, only showy wildflowers are included. These wildflowers are sorted first by flower color, then by plant family (similar flower types), and finally by scientific name within each family. Under each photograph are four lines of information, based on the current standard wild plant reference for California: The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, 1993. Common Name These non-standard names are based on Jepson and other local references. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

2005 Pleasanton Plan 2025

2005 Pleasanton Plan 2025 7. CONSERVATION AND OPEN SPACE ELEMENT Table of Contents page page BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE.................................................. 7-1 Tables SUSTAINABILITY ........................................................................ 7-1 Table 7-1 Potential Wildlife Species of Concern in the RESOURCE CONSERVATION ..................................................... 7-2 Planning Area ........................................................... 7-3 Animal Life.......................................................................... 7-2 Table 7-2 Potential Rare, Threatened, or Endangered Plants Plant Life............................................................................. 7-4 in the Planning Area .................................................. 7-6 Soil Resources ..................................................................... 7-9 Table 7-3 Historic Neighborhoods and Structures ..................... 7-15 Sand and Gravel............................................................... 7-10 Cultural Resources............................................................. 7-11 Figures OPEN SPACE LANDS............................................................... 7-18 Figure 7-1 Generalized Land Cover, 2005 .................................. 7-5 Recreational Open Space................................................... 7-18 Figure 7-2 Aggregate Resources and Reclamation ...................... 7-12 Water Management, Habitat, and Recreation...................... 7-24 Figure 7-3 Historic Neighborhoods -

PA Salamanders

Summer 2012 by Andrew Fedor Longtail Salamander Salamanders are not Pennsylvania’s most noticeable residents. You may have seen them swimming in the weeds near the shore of a lake, crossing roads in the evening after an early spring rain or while flipping over stones and logs Northern Red Salamander in search of other critters. Most of the time, a venomous bite. salamanders are out of Neither of these myths sight or misunderstood. are true. Salamanders Many are small, secretive are spectacular and come out only when animals that are an conditions are right. important part of the Some people think that environment. Read on Four-toed Salamander they are lizards or have to learn all about them. www.fishandboat.com Pennsylvania Angler & Boater • July/August 2012 45 Many salamanders have a life Salamanders and other cycle similar to frogs and toads. amphibians like to breed They begin by emerging from in vernal pools, because eggs as larvae and later change predatory fish do not into adults. This transformation is live there. Many species called metamorphosis. brood or stay with their Adult female salamanders eggs to protect them Marbled Salamander lay eggs in the spring, summer from predators until or fall. The eggs are laid they hatch. individually, in small or large Eggs that are laid in masses or in long strands. Eggs ponds or streams hatch are laid in a moist environment, into larvae that must often a pond or vernal pool but live in the water. The sometimes under rocks or logs. A larvae look like miniature vernal pool is a seasonal pool of adults but with feathery Northern Dusky Salamander water that typically forms in the gills extending near their spring. -

22 Foodplant Ecology of the Butterfly Chlosyne Lacinia

22 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY 1972. Coevolution: patterns of legume predation by a lycaenid butterfly. Oecologia, in press. BRUSSARD, P. F . & P. R. EHRLICH. 1970. Contrasting population biology of two species of butterflies. Nature 227: 91-92. DETmER, V. G. 1959. Food-plant distribution and density and larval dispersal as factors affecting insect populations. Can. Entomol. 91 : 581-596. DOWNEY, J. C. & W. C. FULLER. 1961. Variation in Plebe;us icarioides (Lycaeni dae ) 1. Food-plant specificity. J. Lepid. Soc. 15( 1) : 34-52. EHRLICH, P. R. & P. H. RAVEN. 1964. Butterflies and plants: a study in coevolu tion. Evolution 18: 586-608. GILBERT, L. E. 1971. The effect of resource distribution on population structure in the butterfly Euphydryas editha: Jasper Ridge vs. Del Puerto Canyon colonies. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University. SINGER, M. C. 1971. Evolution of food-plant preference in the butterfly Euphydryas editha. Evolution 25: 383-389. FOODPLANT ECOLOGY OF THE BUTTERFLY CHLOSYNE LACINIA (GEYER) (NYMPHALIDAE). 1. LARVAL FOODPLANTS RAYMOND \;y. NECK D epartment of Zoology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712 For several years I have studied field populations of Chlosyne lacinia ( Geyer) (N ymphalidae: Melitaeini) in central and south Texas for genetic (Neck et aI., 1971) and ecological genetic data. A considerable amount of information concerning foodplants of this species has been collected. Foodplant utilization information is an important base from which ecological studies may emerge. Such information is also invaluable in evaluating the significance of tested foodplant preferences of larvae and adults. Such studies have been under way by other investigators and will be available for comparison with natural population observa tions. -

Cherax Albertisii (Blue Tiger Crayfish) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Blue Tiger Crayfish (Cherax albertisii) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, November 2018 Revised, February 2019 Web Version, 3/29/2019 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Chambers (1987): “Freshwater crayfish (Cherax albertisii) […] occur throughout the shallow lakes and rivers of Western Province [Papua New Guinea].” Status in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. There is no indication that this species is in trade in the United States. Means of Introductions in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. Remarks GBIF Secretariat (2017) refers to this species as the “Papua blue green crayfish.” 1 From Eprilurahman (2014): “Significant taxonomic disputation and confusion has surrounded the number and identity of species that is referred to as the C. quadricarinatus – C. albertisii complex, which are identifiable on the basis of red soft membraneous outer margin of the propodus of the claw. The earliest taxonomic reviewers of the genus Cherax, (Smith 1912; Calman 1911; and Clark 1936), considered there was no justification in considering C. quadricarinatus, a large freshwater crayfish, described by von Martens (1868) from northern Australia to be taxonomically distinct from C. albertisii described by Nobilli (1899) from southern New Guinea. […] In contrast, Holthuis (1949; 1950; 1982) considered C. quadricarinatus, C. albertisii and C. lorentzi to be taxonomically distinct, with the former species restricted to Australia and the later [sic] two species occurring in New Guinea. My results […] support the recognition of C. -

Chapter 28: Arthropods

Chapter 28 Organizer Arthropods Refer to pages 4T-5T of the Teacher Guide for an explanation of the National Science Education Standards correlations. Teacher Classroom Resources Activities/FeaturesObjectivesSection MastersSection TransparenciesReproducible Reinforcement and Study Guide, pp. 123-124 L2 Section Focus Transparency 69 L1 ELL Section 28.1 1. Relate the structural and behavioral MiniLab 28-1: Crayfish Characteristics, p. 763 Section 28.1 adaptations of arthropods to their ability Problem-Solving Lab 28-1, p. 766 BioLab and MiniLab Worksheets, p. 125 L2 Basic Concepts Transparency 49 L2 ELL Characteristics of to live in different habitats. Characteristics Content Mastery, pp. 137-138, 140 L1 Reteaching Skills Transparency 41 L1 ELL Arthropods 2. Analyze the adaptations that make of Arthropods P National Science Education arthropods an evolutionarily successful P Standards UCP.1-5; A.1, A.2; phylum. Reinforcement and Study Guide, pp. 125-126 L2 Section Focus Transparency 70 L1 ELLP C.3, C.5, C.6 (1 session, 1/ Section 28.2 2 Concept Mapping, p. 28 P Reteaching Skills Transparency 41 block) L3 ELL L1LS ELL Diversity of Critical Thinking/Problem Solving, p. 28 L3P Reteaching Skills Transparency 42 PL1 ELL Arthropods P LS BioLab and MiniLab Worksheets, pp. 126-128 L2 P LS Section 28.2 3. Compare and contrast the similarities Inside Story: A Spider, p. 769 Laboratory Manual, pp. 199-204P L2 P P LS P and differences among the major groups Inside Story: A Grasshopper, p. 772 Content Mastery, pp. 137, 139-140 L1 P Diversity of of arthropods. MiniLab 28-2: Comparing Patterns of P LS LS Inside Story Poster ELL P LS Arthropods 4. -

C14 Asters.Sym-Xan

COMPOSITAE PART FOUR Symphyotrichum to Xanthium Revised 1 April 2015 SUNFLOWER FAMILY 4 COMPOSITAE Symphyotrichum Vernonia Tetraneuris Xanthium Verbesina Notes SYMPHYOTRICHUM Nees 1833 AMERICAN ASTER Symphyotrichum New Latin, from Greek symphysis, junction, & trichos, hair, referring to a perceived basal connation of bristles in the European cultivar used by Nees as the type, or from Greek symphyton, neuter of symphytos, grown together. A genus of approximately Copyrighted Draught 80 spp of the Americas & eastern Asia, with the greatest diversity in the southeastern USA (according to one source). Cook Co, Illinois has 24 spp, the highest spp concentration in the country. See also Aster, Eurybia, Doellingeria, Oclemena, & Ionactis. X = 8, 7, 5, 13, 18, & 21. Density gradient of native spp for Symphyotrichum within the US (data 2011). Darkest green (24 spp. Cook Co, IL) indicates the highest spp concentration. ©BONAP Symphyotrichum X amethystinum (Nuttall) Nesom AMETHYST ASTER, Habitat: Mesic prairie. Usually found close to the parents. distribution - range: Culture: Description: Comments: status: phenology: Blooms 9-10. “This is an attractive aster with many heads of blue or purple rays; rarer white and pink-rayed forms also occur. … Disk flowers are perfect and fertile; ray flowers are pistillate and fertile.” (ILPIN) VHFS: Formerly Aster X amethystinus Nutt. Hybrid between S novae-angliae & S ericoides. This is a possible hybrid of Aster novae-angliae and Aster ericoides, or of A. novae-angliae and A. praealtus” (Ilpin) Symphyotrichum X amethystinum Symphyotrichum anomalum (Engelmann) GL Nesom BLUE ASTER, aka LIMESTONE HEART-LEAF ASTER, MANY RAY ASTER, MANYRAY ASTER, MANY-RAYED ASTER, subgenus Symphyotrichum Section Cordifolii Copyrighted Draught Habitat: Dry woods. -

Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts

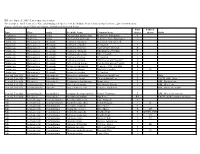

2 0 1 5 – 2 0 2 5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts Appendix 1.4C-Amphibians Amphibian Species of Greatest Conservation Need Maps: Physiographic Provinces and HUC Watersheds Species Accounts (Click species name below or bookmark to navigate to species account) AMPHIBIANS Eastern Hellbender Northern Ravine Salamander Mountain Chorus Frog Mudpuppy Eastern Mud Salamander Upland Chorus Frog Jefferson Salamander Eastern Spadefoot New Jersey Chorus Frog Blue-spotted Salamander Fowler’s Toad Western Chorus Frog Marbled Salamander Northern Cricket Frog Northern Leopard Frog Green Salamander Cope’s Gray Treefrog Southern Leopard Frog The following Physiographic Province and HUC Watershed maps are presented here for reference with conservation actions identified in the species accounts. Species account authors identified appropriate Physiographic Provinces or HUC Watershed (Level 4, 6, 8, 10, or statewide) for specific conservation actions to address identified threats. HUC watersheds used in this document were developed from the Watershed Boundary Dataset, a joint project of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Physiographic Provinces Central Lowlands Appalachian Plateaus New England Ridge and Valley Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain Appalachian Plateaus Central Lowlands Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain New England Ridge and Valley 675| Appendix 1.4 Amphibians Lake Erie Pennsylvania HUC4 and HUC6 Watersheds Eastern Lake Erie -

Argia the News Journal of the Dragonfly Society of the Americas

ISSN 1061-8503 TheA News Journalrgia of the Dragonfly Society of the Americas Volume 22 17 December 2010 Number 4 Published by the Dragonfly Society of the Americas http://www.DragonflySocietyAmericas.org/ ARGIA Vol. 22, No. 4, 17 December 2010 In This Issue .................................................................................................................................................................1 Calendar of Events ......................................................................................................................................................1 Minutes of the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Dragonfly Society of the Americas, by Steve Valley ............................2 2010 Treasurer’s Report, by Jerrell J. Daigle ................................................................................................................2 Enallagma novaehispaniae Calvert (Neotropical Bluet), Another New Species for Arizona, by Rich Bailowitz ......3 Photos Needed ............................................................................................................................................................3 Lestes australis (Southern Spreadwing), New for Arizona, by Rich Bailowitz ...........................................................4 Ischnura barberi (Desert Forktail) Found in Oregon, by Jim Johnson ........................................................................4 Recent Discoveries in Montana, by Nathan S. Kohler ...............................................................................................5 -

Threatened and Endangered Species List

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum