Report on the CAA Summer Meeting 2016 – Vale of Clwyd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDEX to LEAD MINING RECORDS at FLINTSHIRE RECORD OFFICE This Index Is Not Comprehensive but Will Act As a Guide to Our Holdings

INDEX TO LEAD MINING RECORDS AT FLINTSHIRE RECORD OFFICE This index is not comprehensive but will act as a guide to our holdings. The records can only be viewed at Flintshire Record Office. Please make a note of all reference numbers. LOCATION DESCRIPTION DATE REF. NO. Aberduna Lease. 1872 D/KK/1016 Aberduna Report. 1884 D/DM/448/59 Aberdune Share certificates. 1840 D/KK/1553 Abergele Leases. 1771-1790 D/PG/6-7 Abergele Lease. 1738 D/HE/229 Abergele See also Tyddyn Morgan. Afon Goch Mine Lease. 1819 D/DM/1206/1 Anglesey Leases of lead & copper mines in Llandonna & Llanwenllwyfo. 1759-1788 D/PG/1-2 Anglesey Lease & agreement for mines in Llanwenllwyfo. 1763-1764 D/KK/326-7 Ash Tree Work Agreement. 1765 D/PG/11 Ash Tree Work Agreement. 1755 D/MT/105 Barber's Work Takenote. 1729 D/MT/99 Belgrave Plan & sections of Bryn-yr-orsedd, Belgrave & Craig gochmines 19th c D/HM/297-9 Belgrave Section. 1986 D/HM/51 Belgrave Mine, Llanarmon License to assign lease & notice req. performance of lease conditions. 1877-1887 D/GR/393-394 Billins Mine, Halkyn Demand for arrears of royalties & sale poster re plant. 1866 D/GR/578-579 Black Mountain Memo re lease of Black Mountain mine. 19th c D/M/5221 Blaen-y-Nant Mine Co Plan of ground at Pwlle'r Neuad, Llanarmon. 1843 D/GR/1752 Blaen-y-Nant, Llanarmon Letter re takenote. 1871 D/GR/441 Bodelwyddan Abandonment plans of Bodelwyddan lead mine. 1857 AB/44-5 Bodelwyddan Letter re progress of work. -

Welsh Genealogy Pdf Free Download

WELSH GENEALOGY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bruce Durie | 288 pages | 01 Feb 2013 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752465999 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom Welsh Genealogy PDF Book Findmypast also has many other Welsh genealogy records including census returns, the Register, trade directories and newspapers. Judaism has quite a long history in Wales, with a Jewish community recorded in Swansea from around Arthfoddw ap Boddw Ceredigion — Approximately one-sixth of the population, some , people, profess no religious faith whatsoever. Wales Wiki Topics. Owen de la Pole — Brochfael ap Elisedd Powys — Cynan ap Hywel Gwynedd — Retrieved 9 May ". Settlers from Wales and later Patagonian Welsh arrived in Newfoundland in the early 19th century, and founded towns in Labrador 's coast region; in , the ship Albion left Cardigan for New Brunswick , carrying Welsh settlers to Canada; on board were 27 Cardigan families, many of whom were farmers. Media Category Templates WikiProject. Flag of Wales. The high cost of translation from English to Welsh has proved controversial. Maelgwn ap Rhys Deheubarth — Goronwy ap Tudur Hen d. A speaker's choice of language can vary according to the subject domain known in linguistics as code-switching. More Wales Genealogy Record Sources. Dafydd ap Gruffydd — By the 19th century, double names Hastings-Bowen were used to distinguish people of the same surname using a hyphenated mother's maiden name or a location. But if not, take heart because the excellent records kept by our English and Welsh forefathers means that record you need is just am 'r 'n gyfnesaf chornela around the next corner. This site contains a collection of stories, photographs and documents donated by the people of Wales. -

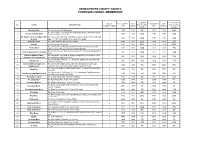

Proposed Arrangements Table

DENBIGHSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP % variance % variance No. OF ELECTORATE 2017 ELECTORATE 2022 No. NAME DESCRIPTION from County from County COUNCILLORS 2017 RATIO 2022 RATIO average average 1 Bodelwyddan The Community of Bodelwyddan 1 1,635 1,635 3% 1,828 1,828 11% The Communities of Cynwyd 468 (494) and Llandrillo 497 (530) and the 2 Corwen and Llandrillo 2 2,837 1,419 -11% 2,946 1,473 -11% Town of Corwen 1,872 (1,922) Denbigh Central and Upper with The Community of Henllan 689 (752) and the Central 1,610 (1,610) and 3 3 4,017 1,339 -16% 4,157 1,386 -16% Henllan Upper 1,718 (1,795) Wards of the Town of Denbigh 4 Denbigh Lower The Lower Ward of the Town of Denbigh 2 3,606 1,803 13% 3,830 1,915 16% 5 Dyserth The Community of Dyserth 1 1,957 1,957 23% 2,149 2,149 30% The Communities of Betws Gwerfil Goch 283 (283), Clocaenog 196 6 Efenechtyd 1 1,369 1,369 -14% 1,528 1,528 -7% (196), Derwen 375 (412) and Efenechtyd 515 (637). The Communities of Llanarmonmon-yn-Ial 900 (960) and Llandegla 512 7 Llanarmon-yn-Iâl and Llandegla 1 1,412 1,412 -11% 1,472 1,472 -11% (512) Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd, The Communities of Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd 669 (727), Llanferres 658 8 1 1,871 1,871 18% 1,969 1,969 19% Llanferres and Llangynhafal (677) and Llangynhafal 544 (565) The Community of Aberwheeler 269 (269), Llandyrnog 869 (944) and 9 Llandyrnog 1 1,761 1,761 11% 1,836 1,836 11% Llanynys 623 (623) Llanfair Dyffryn Clwyd and The Community of Bryneglwys 307 (333), Gwyddelwern 403 (432), 10 1 1,840 1,840 16% 2,056 2,056 25% Gwyddelwern Llanelidan -

Bodelwyddan, St Asaph Manor House Leisure Park Bodelwyddan, St

Bodelwyddan, St Asaph Manor House Leisure Park Bodelwyddan, St. Asaph, Denbighshire, North Wales LL18 5UN Call Roy Kellett Caravans on 01745 350043 for more information or to view this holiday park Park Facilities Local Area Information Bar Launderette Manor House Leisure Park is a tranquil secluded haven nestled in the Restaurant Spa heart of North Wales. Set against the backdrop of the Faenol Fawr Hotel Pets allowed with beautiful stunning gardens, this architectural masterpiece will entice Swimming pool and captivate even the most discerning of critics. Sauna Public footpaths Manor house local town is the town of St Asaph which is nestled in the heart of Denbighshire, North Wales. It is bordered by Rhuddlan to the Locally north, Trefnant to the south, Tremeirchion to the south east and Shops Groesffordd Marli to the west. Nearby towns and villages include Bodelwyddan, Dyserth, Llannefydd, Trefnant, Rhyl, Denbigh, Abergele, Hospital Colwyn Bay and Llandudno. The river Elwy meanders through the town Public footpaths before joining with the river Clwyd just north of St Asaph. Golf course Close to Rhuddlan Town & Bodelwyddan Although a town, St Asaph is often regarded as a city, due to its cathe- Couple minutes drive from A55 dral. Most of the church, however, was built during Henry Tudor's time on the throne and was heavily restored during the 19th century. Today the Type of Park church is a quiet and peaceful place to visit, complete with attractive arched roofs and beautiful stained glass windows. Quiet, peaceful, get away from it all park Exclusive caravan park Grandchildren allowed Park Information Season: 10.5 month season Connection fee: POA Site fee: £2500 inc water Rates: POA Other Charges: Gas piped, Electric metered, water included Call today to view this holiday park. -

Slow Walks Round Ruthin | a Guided Tour Slow Walks Eng 10/2/09 09:29 Page 3

slow walks eng 10/2/09 09:29 Page 2 slow walks round ruthin | a guided tour slow walks eng 10/2/09 09:29 Page 3 introduction This booklet describes three Slow Walks around the streets of Ruthin. Two will take you more or less in a straight line, and one is circular; they all finish in St Peter’s Square in the centre of town. Later in the booklet, the ‘Stepping Out’ section highlights places of interest on the outskirts of Ruthin; these excursions are at opposite ends of the town and it may be best, depending on how fit you are, to take your car, if you have one, to the starting point of each walk. © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Denbighshire County Council. 100023408. 2009. Ruthin is at the crossroads of the A494 (Queensferry to Dolgellau) with the A525 (Rhyl to Whitchurch). It can be reached by bus from Rhyl, Wrexham, Corwen and Llangollen. 2 slow walks eng 10/2/09 09:29 Page 3 slow walks eng 10/2/09 09:29 Page 4 introduction contents This booklet describes three Slow Walks around the streets of Ruthin. Two will take you more or less in a straight line, and one is circular; they all finish in St Peter’s Square in the centre of town. Later in the booklet, the ‘Stepping Out’ section highlights places of interest on the outskirts of Ruthin; these excursions are at opposite ends of the town and it may be best, depending on how fit you are, to take your car, if you have one, to the starting point of each walk. -

Min.298 Minutes of Cyngor Cymuned Aberchwiler – Aberwheeler

Min.298 Minutes of Cyngor Cymuned Aberchwiler – Aberwheeler Community Council Meeting on Wednesday, 12th February, 2020, at 7.00pm in the Waen Chapel School Room. Present: Community Councillors D M Roberts (Chair), H Burton (Vice-Chair), D G Edwards, R Evans, J A Jones, D Williams and the Clerk H Williams. Apologies: Community Councillor H Sweetman and County Councillor M Parry. 10/20 Members of the Public. Nil 11/20 Declaration of Interest. Nil 12/20 Confirmation of Previous Minutes. Accepted as a correct record. 13/20 Matters Arising. Aberwheeler Feasibility Study. The Chairman and the Clerk attended OVW Meeting on Wednesday, 29th January, 2020 at the Town Hall, Denbigh. The Chairman presented a report to the Members. 14/20 Correspondence. OVW – Local Government and Election (Wales) Bill. DCC – Commonwealth Day Flag Raising Ceremony. DCC – Charter between City, Town and Community Councils in Denbighshire. Keep Wales Tidy – Spring Clean Wales 20th March to 13 April. SSAFA – The Armed Forces Charity, VE Day 75 Celebrations. JDH Business Services – Internal Audit Plan Welsh Councils. Urdd Eisteddfod Donation. 15/20 County Councillors Report. Nil. 16/20 Planning. Discussion on the extension to existing agricultural building 09/2019/0078. Located at land adjacent to Efail y Waen. 17/20 Finance. Members approved payments of £100.00 (one hundred pounds) donation to the Denbighshire Urdd Eisteddfod 2020 by cheque No. 100295. OVW payment £53.00 (fifty three pounds) Membership, by cheque No. 100296. GDPR/Data Protection payment £40.00 (forty pounds) by cheque No. 100297. Bal. C/F = £2,700.13p. 18/20 AOM. Clerk to contact County Councillor M Parry regarding Glan Clwyd Lane very muddy also report large tree very dangerous on going down left hand side of Glan Clwyd Lane the 30mph sign near the Cemetery is facing the wrong way round. -

Hen Wrych Llanddulas Road, Abergele LL22 8EU

Gwynt y Mor Project Hen Wrych Llanddulas Road, Abergele LL22 8EU !" #$%&%'(%$$(!%!)&%&*'(!*&#+%,(+%#+*-(%' (!%+%*&'*&&*'('./(!%#+#%+(*%& !)&%!*&(+.+%&%+,! 0 " 0" 0 " 123 1 Contents page 1. Building Description 2 2. Early Background History 4 3. 16th Century 8 4. 17th Century 9 5. 18th Century 12 6. 19th Century 14 7. 20th Century 21 8. 21st Century 29 Appendix 1 The Morgans of Golden Grove 30 Appendix 2 The Royal House of Cunedda 31 Appendix 3 The Lloyd family 32 Appendix 4 John Lloyd 1670 Inventory 34 Appendix 5 John Lloyd 1726 Inventory 38 Appendix 6 The Hesketh Family of Gwrych 40 Appendix 7 The Family of Felicity Hemans 42 Acknowledgements With thanks for the support received from the Gwynt y Mor Community Investment Fund. 1 Building Description Hen Wrych , Llanddulas Road, Abergele, LL22 8EU Grade II listed NPRN 308540 OS map ref. SH97NW Grid Reference SH9279178052 www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk Interior Early C19 stick-baluster, single-flight stair to entrance hall with swept pine rail. Stopped-chamfered beamed ceilings to ground and basement floor rooms, that to former hall framed in three ways, that to basement room at L with broach stops and wall corbelling. Corbelling to the front-facing wall of this room relates to a lateral fireplace in the room above. This has a square-headed, ovolo-moulded C17 sandstone surround; a box-framed oak partition to the L is contemporary, the C17 ovolo- moulded doorcase to which has been removed (for storage) by the present owner (5/97). Wide lateral fireplace to hall (rear range) with primary corbelling supporting a C19 plastered brick arch. -

Dyffryn Clwyd Mission Area

Dyffryn Clwyd Mission Area Application Pack: November 2019 The Diocese of St Asaph In the Diocese of St Asaph or Teulu Asaph, we’re • Growing and encouraging the whole people of God • Enlivening and enriching worship • Engaging the world We’re a family of more than 7,000 regular worshippers, with 80 full time clergy, over 500 lay leaders, 216 churches and 51 church schools. We trace our history to the days of our namesake, St Asaph and his mentor, St Kentigern who it’s believed built a monastery in St Asaph in AD 560. Many of the churches across the Diocese were founded by the earliest saints in Wales who witnessed to Christian faith in Wales and have flourished through centuries of war, upheaval, reformation and reorganisation. Today, the Diocese of St Asaph carries forward that same Mission to share God’s love to all in 21th Century north east and mid Wales. We’re honoured to be a Christian presence in every community, to walk with people on the journey of life and to offer prayers to mark together the milestones of life. Unlocking our Potential is the focus of our response to share God’s love with people across north east and mid Wales. Unlocking our Potential is about bringing change, while remaining faithful to the life-giving message of Jesus. It’s about challenging, inspiring and equipping the whole people of God to grow in their faith. Geographically, the Diocese follows the English/Welsh border in the east, whilst the western edge is delineated by the Conwy Valley. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

Public Document Pack

Public Document Pack Gareth Owens LL.B Barrister/Bargyfreithiwr Head of Legal and Democratic Services Pennaeth Gwasanaethau Cyfreithiol a Democrataidd To: Cllr David Wisinger (Chairman) CS/NG Councillors: Chris Bithell, Derek Butler, David Cox, Ian Dunbar, Carol Ellis, David Evans, Jim Falshaw, 29 October 2013 Veronica Gay, Alison Halford, Ron Hampson, Ray Hughes, Christine Jones, Richard Jones, Tracy Waters 01352 702331 Brian Lloyd, Billy Mullin, Mike Peers, [email protected] Neville Phillips, Gareth Roberts, Carolyn Thomas and Owen Thomas Dear Sir / Madam A meeting of the PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT CONTROL COMMITTEE will be held in the COUNCIL CHAMBER, COUNTY HALL, MOLD CH7 6NA on WEDNESDAY, 6TH NOVEMBER, 2013 at 1.00 PM to consider the following items. Yours faithfully Democracy & Governance Manager A G E N D A 1 APOLOGIES 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 3 LATE OBSERVATIONS 4 MINUTES (Pages 1 - 22) To confirm as a correct record the minutes of the meeting held on 9 th October 2013. 5 ITEMS TO BE DEFERRED County Hall, Mold. CH7 6NA Tel. 01352 702400 DX 708591 Mold 4 www.flintshire.gov.uk Neuadd y Sir, Yr Wyddgrug. CH7 6NR Ffôn 01352 702400 DX 708591 Mold 4 www.siryfflint.gov.uk The Council welcomes correspondence in Welsh or English Mae'r Cyngor yn croesawau gohebiaeth yn y Cymraeg neu'r Saesneg 6 REPORTS OF HEAD OF PLANNING The report of the Head of Planning is enclosed. REPORT OF HEAD OF PLANNING TO PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT CONTROL COMMITTEE ON 6TH NOVEMBER 2013 Item File Reference DESCRIPTION No (A=reported for approval, R=reported for refusal) 6.1 051266 - A Full Application - Erection of 37 No. -

Memoirs of the Civil War in Wales and the Marches

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE DOCUMENTS. CAKMAKTHEN : " ' MORGAN AND DAVIES, WELSHMAN 1871. MEMOIRS OP THE CIVIL WAR IN WALES AND THE MARCHES. 16421649. BT JOHN ROLAND PHILLIPS OK LINCOLN'S INN, BABEISTKB-AT-LAW. IN TWO VOLUMES. YOL. II. LONDON I LONGMANS, GREEN, & Co. 1874. V, X CONTENTS. DOCUMENT PAGE I. A Petition from Flintshire to the King at York. August, 1642 1 II. Parliament Order to call out Militia in Pembrokeshire 4 III. Chester declares against the Array. August 8 IV. The King at Shrewsbury and Chester, various letters. Sept. ... 10 V. Marquis of Hertford takes Cardiff for the King. Aug. 23 VI. Visit of Prince of Wales to Raglan Castle. Oct. ... 26 VII. Hint at Shrewsbury the King departs thence. Oct. 30 VIII. Nantwich in trouble for opposing the King 33 IX. After the battle of Edghill old Rhyme. 36 X. Welsh under Marquis of Hertford defeated at Tewkesbury. Dec. 38 XI. Shropshire Royalists' resolution for the King. Dec. 42 XII. Agreement of Neutrality in Cheshire. Dec. 44 XIII. The History of the Cheshire Neutrality 46 XIV. Fight at Middlewich Sir W. Brereton defeats Royalists. Jan. 1643 49 XV. Battle of Torperley. Feb. 21. 52 XVI. Brereton' s Account of Battle of Middlewich 54 XVII. Sir Thomas Aston' s Account ditto 56 XVIII. List of Prisoners ditto 62 XIX. Defeat of Lord Herbert at Gloucester. March 25 ... 63 XX. Monmouth and Chepstow taken by Waller 66 XXI. Surrender of Hereford. April 25 69 XXII. Sir Thomas Myddelton's Commission as Major-General of North Wales .. -

RUTHIN CASTLE: a PRIVATE HOSPITAL for the INVESTIGATION and TREATMENT of OBSCURE MEDICAL DISEASES (1923-1950) by R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central RUTHIN CASTLE: A PRIVATE HOSPITAL FOR THE INVESTIGATION AND TREATMENT OF OBSCURE MEDICAL DISEASES (1923-1950) by R. S. ALLISON, V.R.D., M.D., D.Sc., F.R.C.P. Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast A LESSER-KNOWN development in medicine in Great Britain was the opening in 1923 of Ruthin Castle, North Wales, the first private hospital for the investigation and treatment of obscure internal diseases. Apart from the inevitable publicity it evoked, and although the clinic acquired a wide reputation, it remained unadver- tised except for a regular notice in the Quarterly Journal of Medicine. This announced simply that pati- ents could be received for investigation and treatment on the authority of their doctor and that mental cases would not be accept- ed. It also commented briefly on the historic setting of the Castle and the beauty of its environ- ment. The clinical director was Doctor, later Sir Edmund Ivens Spriggs, K.C.V.O., M.D., F.R.C.P., J.P., who for years had been a con- sultant physician on the staff of St. George's Hos- pital, London, following an academic career in which his training in physiology had played a major part. His withdrawal from prac- tice in London in 1910 was brought about by a severe illness: pleurisy with effu- sion, after which in due course he was persuaded not to return to London but 22 to take on the clinical directorship of a small private hospital at Duff House, Banff, designed for medical cases rather than tuberculosis, which was managed and financed by a group of doctors, notably Dr.