Historic Settlements in Denbighshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

233 08 SD50 Environment Permitting Decision Document

Natural Resources Wales permitting decisions Pencraig Fawr Broiler Unit Decision Document www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk Issued XX XX 2019 Page 1 of 21 New bespoke permit The application number is: PAN-003738 The Applicant / Operator is: Mr Robert Gwyn Edwards, Mrs Joan Lynn Edwards, Mr Dion Gwyn Edwards and Mr Robert Cai Edwards The Installation is located at: Pencraig Fawr, Betws Gwerfil Goch, Corwen, Denbighshire, LL21 9PL We have decided to grant the permit for Pencraig Fawr Broiler Unit operated by Mr Robert Gwyn Edwards, Mrs Joan Lynn Edwards, Mr Dion Gwyn Edwards and Mr Robert Cai Edwards. We consider in reaching that decision we have taken into account all relevant considerations and legal requirements and that the permit will ensure that the appropriate level of environmental protection is provided. Purpose of this document This decision document: • explains how the application has been determined • provides a record of the decision-making process • shows how all relevant factors have been taken into account • justifies the specific conditions in the permit other than those in our generic permit template. Unless the decision document specifies otherwise we have accepted the applicant’s proposals. Structure of this document • Table of contents • Key issues • Annex 1 the consultation and web publicising responses www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk Issued XX XX 2019 Page 2 of 21 Table of Contents Contents New bespoke permit................................................................................................... 2 The application number is: PAN-003738 ................................................................ 2 The Applicant / Operator is: Mr Robert Gwyn Edwards, Mrs Joan Lynn Edwards, Mr Dion Gwyn Edwards and Mr Robert Cai Edwards .................................................. 2 The Installation is located at: Pencraig Fawr, Betws Gwerfil Goch, Corwen, Denbighshire, LL21 9PL ........................................................................................ -

North Wales Wind Farms Connection

North Wales Wind Farms Connection Welcome to our Exhibition Who is SP Manweb? SP Manweb holds the electricity distribution licence for Merseyside, Cheshire and North Wales. It is part of ScottishPower, itself a subsidiary of the Spanish company Iberdrola. Background to the Project The UK faces a major challenge with increasing demands for energy at a time when ageing power plants are closing and there is an urgent need to tackle climate change by reducing emissions. To meet this challenge, the Welsh Government is seeking to cut emissions and increase new low carbon energy generation. The new energy will need connecting into the high-voltage electricity transmission network. It is SP Manweb’s responsibility to do this in a safe, reliable and efficient way. This includes ensuring that the network has enough capacity to move electricity across the system from areas of generation to areas of demand, connecting new electricity generators such as wind farms to the distribution networks. Work in North Wales North Wales has been identified as an important location for renewable energy generation. There are a number of developers who are proposing to build wind farms in the area and SP Manweb is working closely with them. The proposed wind farms are concentrated in and around TAN8 Area A – one of the seven areas identified in Tan 8 Areas the Welsh Government’s Technical Advice Note (TAN) 8: Planning for Renewable Energy, as being relatively unconstrained and capable of accommodating large scale wind power developments. TAN 8 suggests that Area A could have an indicative generating capacity of 140 MW. -

Bibliography Refresh March 2017

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Version 03, Bibliography Refresh March 2017 Medieval Bibliography of Medieval references (Wales) 2012 ‐ 2016 Adams, M., 2015 ‘A study of the magnificent remnant of a Tree Jesse at St Mary’s Priory Church, Abergavenny: Part One’, Monmouthshire Antiquary, 31, 45‐62. Adams, M., 2016 ‘A study of the magnificent remnant of a Tree Jesse at St Mary’s Priory Church, Abergavenny: Part Two, Monmouthshire Antiquary, 32, 101‐114. Allen, A. S., 2016 ‘Church Orientation in the Landscape: a perspective from Medieval Wales’, Archaeological Journal, 173, 154‐187. Austin, D., 2016 ‘Reconstructing the upland landscapes of medieval Wales’, Archaeologia Cambrensis 165, 1‐19. Baker, K., Carden, R., and Madgwick,, R. 2014 Deer and People, Windgather Press, Oxford. Barton, P. G., 2013 ‘Powis Castle Middle Park motte and bailey’, Castle Studies Group Journal, 26, 185‐9. Barton, P. G., 2013 ‘Welshpool ‘motte and bailey’, Montgomeryshire Collections 101 (2013), 151‐ 154. Barton, P.G., 2014 ‘The medieval borough of Caersws: origins and decline’. Montgomeryshire Collections 102, 103‐8. Brennan, N., 2015 “’Devoured with the sands’: a Time Team evaluation at Kenfig, Bridgend, Glamorgan”, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 164 (2015), 221‐9. Brodie, H., 2015 ‘Apsidal and D‐shaped towers of the Princes of Gwynedd’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 164 (2015), 231‐43. Burton, J., and Stöber, K. (ed), 2013 Monastic Wales New Approaches, University of Wales Press, Cardiff Burton, J., and Stöber, K., 2015 Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, University of Wales Press, Cardiff Caple, C., 2012 ‘The apotropaic symbolled threshold to Nevern Castle – Castell Nanhyfer’, Archaeological Journal, 169, 422‐52 Carr, A. -

Country Codes HI Channel Islands ENG England IOM Isle of Man IRL

Country codes HI Channel Islands Scotland, Ancient counties ENG England ABD Aberdeenshire IOM Isle of Man ANS Angus (formerly Forfarshire) IRL Ireland ARL Argyll (Argyllshire) NIR Northern Ireland AYR Ayrshire SCT Scotland BAN Banffshire WLS Wales BEW Berwickshire ALL All countries BUT Bute (Buteshire) Channel Islands CAI Caithness ALD Alderney CLK Clackmannanshire GSY Guernsey DFS Dumfriesshire JSY Jersey DNB Dunbartonshire SRK Sark ELN East Lothian (form. Haddingtonshire) England, Ancient counties FIF Fife BDF Bedfordshire INV Inverness-shire BRK Berkshire KCD Kincardineshire BKM Buckinghamshire KRS Kinross-shire CAM Cambridgeshire KKD Kirkcudbrightshire CHS Cheshire LKS Lanarkshire CON Cornwall MLN Midlothian (form. Edinburghshire) CUL Cumberland MOR Moray (form. Elginshire) DBY Derbyshire NAI Nairnshire DEV Devonshire OKI Orkney DOR Dorset PEE Peeblesshire DUR Durham PER Perthshire ESS Essex RFW Renfrewshire GLS Gloucestershire ROC Ross and Cromarty HAM Hampshire ROX Roxburghshire HEF Herefordshire SEL Selkirkshire HRT Hertfordshire SHI Shetland HUN Huntingdonshire STI Stirlingshire IOW Isle of Wight SUT Sutherland KEN Kent WLN West Lothian (form. Linlithgowshire) LAN Lancashire WIG Wigtownshire LEI Leicestershire LIN Lincolnshire 1975-1996 regions LND London (City only) BOR Borders MDX Middlesex CEN Central NFK Norfolk DGY Dumfries and Galloway NTH Northamptonshire FIF Fife NBL Northumberland GMP Grampian NTT Nottinghamshire HLD Highland OXF Oxfordshire LTN Lothian RUT Rutland OKI Orkney Ises SAL Shropshire SHI Shetland Isles SOM -

Ffrith Y Geubren, Cyffylliog, Ruthin, Denbighshire, Ll15 2Bu Ffrith Y Geubren Cyffylliog, Ruthin, Denbighshire, Ll15 2Bu

FFRITH Y GEUBREN, CYFFYLLIOG, RUTHIN, DENBIGHSHIRE, LL15 2BU FFRITH Y GEUBREN CYFFYLLIOG, RUTHIN, DENBIGHSHIRE, LL15 2BU Only recently completed, a beautifully appointed, greatly extended four bedroom period farmhouse set within extensive landscaped gardens with three spring-fed ponds together a modern purpose built multi-purpose stock shed, stables and yard, 40m x 20m all weather manège, kennels and land extending in total to about 13.9 acres. Located in an enviable position amidst rolling countryside and with far reaching views towards the Clwydian Hills, it is almost equidistant between the market towns of Ruthin and Denbigh. Ffrith y Geubren stands in an elevated position to the southern side of the Vale of Clwyd off minor country lanes which lead from Bontuchel and Llanrhaeadr. It is an area noted for its many quiet country lanes and bridle paths, and whilst secluded it is within easy reach of the A525 at Llanrhaeadr providing access towards Ruthin, Denbigh and the A55 interchange at either St Asaph or Caerwys. ADDITIONAL PASTURE LAND WITH STABLES, FIELD SHELTER AND WOODLAND EXTENDING IN TOTAL TO ABOUT 19.2 ACRES IS AVAILABLE BY SEPARATE NEGOTIATION. Mold 15 miles, Chester 31 miles, Ruthin 5 miles. THE ACCOMMODATION COMPRISES Oak panelled stable door leading to: ELEGANT RECEPTION HALL 11’ x 13’3 (3.35m x 4.04m) With heavy beamed ceiling, turned solid oak staircase rising off with burr oak handrail and square spindles to a galleried landing. Two double glazed windows with slate sills and stone flooring. Fine oak screen to: INNER HALL 11’5 x 12’10 (3.48m x 3.91m) With feature exposed stonework to the outer wall and an original chimney breast with a freestanding Jotul multi- fuel fire grate, heavy beamed ceiling, high level window to rear with sill, wall light point, display niche and stone floor. -

The London Gazette, December 7, 1883

6312 THE LONDON GAZETTE, DECEMBER 7, 1883, county of Denbigh comprising the parishes, of Staff Corps, by Catherine, his wife, daughter of Clocaenog, Efenechtyd, Gryffylliog, . Llanbedr, Thomas Wentworth Buller, Commander in Her Llanelidan, Llanganhafal^ ,and Llanychan, and Majesty's Fleet, and niece of James Buller, those portions of the parishes of LlanfairdyiFryn- late of Dunjey aforesaid, Esquire, both deceased, clwyd, Llanynys, Llanrhydd, and , Llanfcwrog Her Royal licence and authority that he and his which are not in the borough of Ruthin^ in the issue may, in compliance with a clause contained petty sessional of Ruthin, and also the parishes in the last will and testament of his maternal of Llandyrnog, Llangwyfen, and Nantglyn, the great uncle, the said James Buller, assume the townships of Aberwheeler$ Penbedw, Wigfair, surname of Buller in addition to and after that of and Meriadcg, and those portions of the parishes Hughes, and that ,he and they may bear the arms of Henllan, and Llanrhaiadr-yn-Cinmerch which of Bulier quarterly with those of his and their are not in the borough of Denbigh, in the petty own family ; such arms being first duly exemplified sessional division of Isaled,—which was declared according to the laws of arms and recorded in the by Order of Council dated the eleventh day of College of Arms, otherwise the said Royal licence September, one thousand eight hundred and and. permission to be void .and of none effect: eighty-three, to be an Area infected with foot- And to command that the said Royal concession and-mouth disease, is hereby declared to be ,free and declaration be recorded in Her Majesty's from foot-and-mouth disease, and that Area shall, College of Arms. -

Proposed Arrangements Table

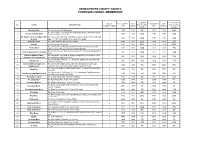

DENBIGHSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP % variance % variance No. OF ELECTORATE 2017 ELECTORATE 2022 No. NAME DESCRIPTION from County from County COUNCILLORS 2017 RATIO 2022 RATIO average average 1 Bodelwyddan The Community of Bodelwyddan 1 1,635 1,635 3% 1,828 1,828 11% The Communities of Cynwyd 468 (494) and Llandrillo 497 (530) and the 2 Corwen and Llandrillo 2 2,837 1,419 -11% 2,946 1,473 -11% Town of Corwen 1,872 (1,922) Denbigh Central and Upper with The Community of Henllan 689 (752) and the Central 1,610 (1,610) and 3 3 4,017 1,339 -16% 4,157 1,386 -16% Henllan Upper 1,718 (1,795) Wards of the Town of Denbigh 4 Denbigh Lower The Lower Ward of the Town of Denbigh 2 3,606 1,803 13% 3,830 1,915 16% 5 Dyserth The Community of Dyserth 1 1,957 1,957 23% 2,149 2,149 30% The Communities of Betws Gwerfil Goch 283 (283), Clocaenog 196 6 Efenechtyd 1 1,369 1,369 -14% 1,528 1,528 -7% (196), Derwen 375 (412) and Efenechtyd 515 (637). The Communities of Llanarmonmon-yn-Ial 900 (960) and Llandegla 512 7 Llanarmon-yn-Iâl and Llandegla 1 1,412 1,412 -11% 1,472 1,472 -11% (512) Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd, The Communities of Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd 669 (727), Llanferres 658 8 1 1,871 1,871 18% 1,969 1,969 19% Llanferres and Llangynhafal (677) and Llangynhafal 544 (565) The Community of Aberwheeler 269 (269), Llandyrnog 869 (944) and 9 Llandyrnog 1 1,761 1,761 11% 1,836 1,836 11% Llanynys 623 (623) Llanfair Dyffryn Clwyd and The Community of Bryneglwys 307 (333), Gwyddelwern 403 (432), 10 1 1,840 1,840 16% 2,056 2,056 25% Gwyddelwern Llanelidan -

Bodelwyddan, St Asaph Manor House Leisure Park Bodelwyddan, St

Bodelwyddan, St Asaph Manor House Leisure Park Bodelwyddan, St. Asaph, Denbighshire, North Wales LL18 5UN Call Roy Kellett Caravans on 01745 350043 for more information or to view this holiday park Park Facilities Local Area Information Bar Launderette Manor House Leisure Park is a tranquil secluded haven nestled in the Restaurant Spa heart of North Wales. Set against the backdrop of the Faenol Fawr Hotel Pets allowed with beautiful stunning gardens, this architectural masterpiece will entice Swimming pool and captivate even the most discerning of critics. Sauna Public footpaths Manor house local town is the town of St Asaph which is nestled in the heart of Denbighshire, North Wales. It is bordered by Rhuddlan to the Locally north, Trefnant to the south, Tremeirchion to the south east and Shops Groesffordd Marli to the west. Nearby towns and villages include Bodelwyddan, Dyserth, Llannefydd, Trefnant, Rhyl, Denbigh, Abergele, Hospital Colwyn Bay and Llandudno. The river Elwy meanders through the town Public footpaths before joining with the river Clwyd just north of St Asaph. Golf course Close to Rhuddlan Town & Bodelwyddan Although a town, St Asaph is often regarded as a city, due to its cathe- Couple minutes drive from A55 dral. Most of the church, however, was built during Henry Tudor's time on the throne and was heavily restored during the 19th century. Today the Type of Park church is a quiet and peaceful place to visit, complete with attractive arched roofs and beautiful stained glass windows. Quiet, peaceful, get away from it all park Exclusive caravan park Grandchildren allowed Park Information Season: 10.5 month season Connection fee: POA Site fee: £2500 inc water Rates: POA Other Charges: Gas piped, Electric metered, water included Call today to view this holiday park. -

The Caernarfonshire Eagles: Development of a Traditional Emblem and County Flag

The Association of British Counties The Caernarfonshire Eagles: Development of a Traditional Emblem and County Flag by Philip S. Tibbetts & Jason Saber - 2 - Contents Essay.......................................................................................................................................................3 Appendix: Timeline..............................................................................................................................16 Bibliography Books.......................................................................................................................................17 Internet....................................................................................................................................18 List of Illustrations Maredudd ap Ieuan ap Robert Memorial..............................................................................................4 Wynn of Gwydir Monument.................................................................................................................4 Blayney Room Carving...........................................................................................................................5 Scott-Giles Illustration of Caernarfonshire Device.................................................................................8 Cigarette Card Illustration of Caernarvon Device..................................................................................8 Caernarfonshire Police Constabulary Helmet Plate...............................................................................9 -

Chapman, 2013) Anglesey Bridge of Boats Documentary and Historical (Menai and Anglesey) Research (Chapman, 2013)

MEYSYDD BRWYDRO HANESYDDOL HISTORIC BATTLEFIELDS IN WALES YNG NGHYMRU The following report, commissioned by Mae’r adroddiad canlynol, a gomisiynwyd the Welsh Battlefields Steering Group and gan Grŵp Llywio Meysydd Brwydro Cymru funded by Welsh Government, forms part ac a ariennir gan Lywodraeth Cymru, yn of a phased programme of investigation ffurfio rhan o raglen archwilio fesul cam i undertaken to inform the consideration of daflu goleuni ar yr ystyriaeth o Gofrestr a Register or Inventory of Historic neu Restr o Feysydd Brwydro Hanesyddol Battlefields in Wales. Work on this began yng Nghymru. Dechreuwyd gweithio ar in December 2007 under the direction of hyn ym mis Rhagfyr 2007 dan the Welsh Government’sHistoric gyfarwyddyd Cadw, gwasanaeth Environment Service (Cadw), and followed amgylchedd hanesyddol Llywodraeth the completion of a Royal Commission on Cymru, ac yr oedd yn dilyn cwblhau the Ancient and Historical Monuments of prosiect gan Gomisiwn Brenhinol Wales (RCAHMW) project to determine Henebion Cymru (RCAHMW) i bennu pa which battlefields in Wales might be feysydd brwydro yng Nghymru a allai fod suitable for depiction on Ordnance Survey yn addas i’w nodi ar fapiau’r Arolwg mapping. The Battlefields Steering Group Ordnans. Sefydlwyd y Grŵp Llywio was established, drawing its membership Meysydd Brwydro, yn cynnwys aelodau o from Cadw, RCAHMW and National Cadw, Comisiwn Brenhinol Henebion Museum Wales, and between 2009 and Cymru ac Amgueddfa Genedlaethol 2014 research on 47 battles and sieges Cymru, a rhwng 2009 a 2014 comisiynwyd was commissioned. This principally ymchwil ar 47 o frwydrau a gwarchaeau. comprised documentary and historical Mae hyn yn bennaf yn cynnwys ymchwil research, and in 10 cases both non- ddogfennol a hanesyddol, ac mewn 10 invasive and invasive fieldwork. -

Where Clwyd Alyn Has Homes Areas & Types Of

WHERE CLWYD ALYN HAS HOMES AREAS & TYPES OF ACCOMMODATION Wrexham County Council No. of Town/Village Dwelling Type Type of Accommodation Units Acrefair 54 1/2 Bed Flats Extra Care 54 Acton 3 3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 3 Bradley 1 3 Bed House Rented Accommodation 1 3 Bed Bungalow Shared Ownership 2 Brymbo 9 2/3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 9 Brynteg 23 1 Bed Flats Rented Accommodation 35 2 Bed Flats Rented Accommodation 10 2 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 31 3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 1 6 Bed House Rented Accommodation 100 Cefn Mawr 4 3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 4 Cefn-Y-Bedd 1 2 Bed House Rented Accommodation 1 Chirk 12 2 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 10 3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 1 3 Bed House Shared Ownership 23 Coedpoeth 2 3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 5 2 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 4 3 Bed Family Houses Shared Ownership 11 Gwersyllt 2 2 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 3 3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 2 4 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 1 2 Bed House Shared Ownership 8 Johnstown 1 2 Bed Bungalow Rented Accommodation 4 2/3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 1 3 Bed House Shared Ownership 6 Llay 1 2 Bed House Rented Accommodation 3 3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 4 Marchwiel 4 2 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 1 3 Bed Bungalow Rented Accommodation 5 New Broughton 1 2 Bed House Rented Accommodation 1 Penley 12 2/3 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 12 Pentre Broughton 2 1 Bed Houses Rented Accommodation 1 2 Bed House Rented Accommodation 3 Pen-Y-Cae 2 2 Bed Bungalows Rented Accommodation 8 3 Bed -

The Offa's Dyke Guided Trail Holiday

The Offa's Dyke Guided Trail Holiday Tour Style: Guided Trails Destination: Wales Trip code: ZDLDW Trip Walking Grade: 5 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW This 177 mile long trail follows the spectacular Dyke that was constructed in the 8th century by King Offa to divide the kingdoms of Mercia and Wales. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Group transfer from Chepstow Station on arrival day and to Chester on departure day • Full board en-suite accommodation • Experienced HF Holidays’ trails leader • All transport to and from the walks • Luggage transfer between accommodation • Group transfer from Chepstow Station on arrival day and to Chester on departure day HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Follow the spectacular Dyke built in the 8th century by King Offa • A remote trail along the undulating borderlands of England and Wales www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • Walk through the Black Mountains, the Shropshire Hills and the Clwydian Hills TRIP SUITABILITY This Guided Walking/Hiking Trail is graded 5. This holiday is recommended for fit and experienced walkers only. It is your responsibility to ensure you have the relevant fitness and equipment required to join this holiday. This strenuous trail covers rough and challenging terrain along the Wales/England border. There are some long days and terrain is at times rough underfoot with many steep and lengthy ascents. A sustained effort is required to complete this trail and provision cannot be made for anyone who opts out. Please be sure you can manage the daily mileage and ascents in the daily itineraries. The walking day is normally 6 to 8 hours, it is important for your own and your fellow guests’ enjoyment that you can maintain the pace.