Chapman, 2013) Anglesey Bridge of Boats Documentary and Historical (Menai and Anglesey) Research (Chapman, 2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography Refresh March 2017

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Version 03, Bibliography Refresh March 2017 Medieval Bibliography of Medieval references (Wales) 2012 ‐ 2016 Adams, M., 2015 ‘A study of the magnificent remnant of a Tree Jesse at St Mary’s Priory Church, Abergavenny: Part One’, Monmouthshire Antiquary, 31, 45‐62. Adams, M., 2016 ‘A study of the magnificent remnant of a Tree Jesse at St Mary’s Priory Church, Abergavenny: Part Two, Monmouthshire Antiquary, 32, 101‐114. Allen, A. S., 2016 ‘Church Orientation in the Landscape: a perspective from Medieval Wales’, Archaeological Journal, 173, 154‐187. Austin, D., 2016 ‘Reconstructing the upland landscapes of medieval Wales’, Archaeologia Cambrensis 165, 1‐19. Baker, K., Carden, R., and Madgwick,, R. 2014 Deer and People, Windgather Press, Oxford. Barton, P. G., 2013 ‘Powis Castle Middle Park motte and bailey’, Castle Studies Group Journal, 26, 185‐9. Barton, P. G., 2013 ‘Welshpool ‘motte and bailey’, Montgomeryshire Collections 101 (2013), 151‐ 154. Barton, P.G., 2014 ‘The medieval borough of Caersws: origins and decline’. Montgomeryshire Collections 102, 103‐8. Brennan, N., 2015 “’Devoured with the sands’: a Time Team evaluation at Kenfig, Bridgend, Glamorgan”, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 164 (2015), 221‐9. Brodie, H., 2015 ‘Apsidal and D‐shaped towers of the Princes of Gwynedd’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 164 (2015), 231‐43. Burton, J., and Stöber, K. (ed), 2013 Monastic Wales New Approaches, University of Wales Press, Cardiff Burton, J., and Stöber, K., 2015 Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, University of Wales Press, Cardiff Caple, C., 2012 ‘The apotropaic symbolled threshold to Nevern Castle – Castell Nanhyfer’, Archaeological Journal, 169, 422‐52 Carr, A. -

Country Codes HI Channel Islands ENG England IOM Isle of Man IRL

Country codes HI Channel Islands Scotland, Ancient counties ENG England ABD Aberdeenshire IOM Isle of Man ANS Angus (formerly Forfarshire) IRL Ireland ARL Argyll (Argyllshire) NIR Northern Ireland AYR Ayrshire SCT Scotland BAN Banffshire WLS Wales BEW Berwickshire ALL All countries BUT Bute (Buteshire) Channel Islands CAI Caithness ALD Alderney CLK Clackmannanshire GSY Guernsey DFS Dumfriesshire JSY Jersey DNB Dunbartonshire SRK Sark ELN East Lothian (form. Haddingtonshire) England, Ancient counties FIF Fife BDF Bedfordshire INV Inverness-shire BRK Berkshire KCD Kincardineshire BKM Buckinghamshire KRS Kinross-shire CAM Cambridgeshire KKD Kirkcudbrightshire CHS Cheshire LKS Lanarkshire CON Cornwall MLN Midlothian (form. Edinburghshire) CUL Cumberland MOR Moray (form. Elginshire) DBY Derbyshire NAI Nairnshire DEV Devonshire OKI Orkney DOR Dorset PEE Peeblesshire DUR Durham PER Perthshire ESS Essex RFW Renfrewshire GLS Gloucestershire ROC Ross and Cromarty HAM Hampshire ROX Roxburghshire HEF Herefordshire SEL Selkirkshire HRT Hertfordshire SHI Shetland HUN Huntingdonshire STI Stirlingshire IOW Isle of Wight SUT Sutherland KEN Kent WLN West Lothian (form. Linlithgowshire) LAN Lancashire WIG Wigtownshire LEI Leicestershire LIN Lincolnshire 1975-1996 regions LND London (City only) BOR Borders MDX Middlesex CEN Central NFK Norfolk DGY Dumfries and Galloway NTH Northamptonshire FIF Fife NBL Northumberland GMP Grampian NTT Nottinghamshire HLD Highland OXF Oxfordshire LTN Lothian RUT Rutland OKI Orkney Ises SAL Shropshire SHI Shetland Isles SOM -

North Wales PREPARING for EMERGENCIES Contents

North Wales PREPARING FOR EMERGENCIES Contents introduction 4 flooding 6 severe weather 8 pandemic 10 terrorist incidents 12 industrial incidents 14 loss of critical infrastructure 16 animal disease 18 pollution 20 transport incidents 22 being prepared in the home 24 businesses being prepared 26 want to know more? 28 Published: Autumn 2020 introduction As part of the work of agencies involved in responding the counties of Cheshire and data), which is largely preparing for emergencies to emergencies – the Shropshire) and to the South by concentrated in the more across the region, key emergency services, local the border with mid-Wales industrial and urbanised areas partners work together to authorities, health, environment (specifically the counties of of the North East and along prepare the North Wales and utility organisations. Powys and Ceredigion). the North Wales coast. The Community Risk Register. population increases significantly The overall purpose is to ensure The land area of North Wales is during summer months. Less This document provides representatives work together to approximately 6,172 square than a quarter (22.32%) of the information on the biggest achieve an appropriate level of kilometres (which equates to total Welsh population lives in emergencies that could happen preparedness to respond to 29% of the total land area of North Wales. in the region and includes the emergencies that may have a Wales), and the coastline is impact on people, communities, significant impact on the almost 400 kilometres long. Over the following pages, we the environment and local communities of North Wales. will look at the key risks we face North Wales is divided into six businesses. -

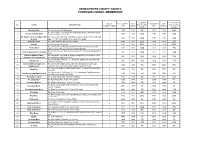

Proposed Arrangements Table

DENBIGHSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP % variance % variance No. OF ELECTORATE 2017 ELECTORATE 2022 No. NAME DESCRIPTION from County from County COUNCILLORS 2017 RATIO 2022 RATIO average average 1 Bodelwyddan The Community of Bodelwyddan 1 1,635 1,635 3% 1,828 1,828 11% The Communities of Cynwyd 468 (494) and Llandrillo 497 (530) and the 2 Corwen and Llandrillo 2 2,837 1,419 -11% 2,946 1,473 -11% Town of Corwen 1,872 (1,922) Denbigh Central and Upper with The Community of Henllan 689 (752) and the Central 1,610 (1,610) and 3 3 4,017 1,339 -16% 4,157 1,386 -16% Henllan Upper 1,718 (1,795) Wards of the Town of Denbigh 4 Denbigh Lower The Lower Ward of the Town of Denbigh 2 3,606 1,803 13% 3,830 1,915 16% 5 Dyserth The Community of Dyserth 1 1,957 1,957 23% 2,149 2,149 30% The Communities of Betws Gwerfil Goch 283 (283), Clocaenog 196 6 Efenechtyd 1 1,369 1,369 -14% 1,528 1,528 -7% (196), Derwen 375 (412) and Efenechtyd 515 (637). The Communities of Llanarmonmon-yn-Ial 900 (960) and Llandegla 512 7 Llanarmon-yn-Iâl and Llandegla 1 1,412 1,412 -11% 1,472 1,472 -11% (512) Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd, The Communities of Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd 669 (727), Llanferres 658 8 1 1,871 1,871 18% 1,969 1,969 19% Llanferres and Llangynhafal (677) and Llangynhafal 544 (565) The Community of Aberwheeler 269 (269), Llandyrnog 869 (944) and 9 Llandyrnog 1 1,761 1,761 11% 1,836 1,836 11% Llanynys 623 (623) Llanfair Dyffryn Clwyd and The Community of Bryneglwys 307 (333), Gwyddelwern 403 (432), 10 1 1,840 1,840 16% 2,056 2,056 25% Gwyddelwern Llanelidan -

Bodelwyddan, St Asaph Manor House Leisure Park Bodelwyddan, St

Bodelwyddan, St Asaph Manor House Leisure Park Bodelwyddan, St. Asaph, Denbighshire, North Wales LL18 5UN Call Roy Kellett Caravans on 01745 350043 for more information or to view this holiday park Park Facilities Local Area Information Bar Launderette Manor House Leisure Park is a tranquil secluded haven nestled in the Restaurant Spa heart of North Wales. Set against the backdrop of the Faenol Fawr Hotel Pets allowed with beautiful stunning gardens, this architectural masterpiece will entice Swimming pool and captivate even the most discerning of critics. Sauna Public footpaths Manor house local town is the town of St Asaph which is nestled in the heart of Denbighshire, North Wales. It is bordered by Rhuddlan to the Locally north, Trefnant to the south, Tremeirchion to the south east and Shops Groesffordd Marli to the west. Nearby towns and villages include Bodelwyddan, Dyserth, Llannefydd, Trefnant, Rhyl, Denbigh, Abergele, Hospital Colwyn Bay and Llandudno. The river Elwy meanders through the town Public footpaths before joining with the river Clwyd just north of St Asaph. Golf course Close to Rhuddlan Town & Bodelwyddan Although a town, St Asaph is often regarded as a city, due to its cathe- Couple minutes drive from A55 dral. Most of the church, however, was built during Henry Tudor's time on the throne and was heavily restored during the 19th century. Today the Type of Park church is a quiet and peaceful place to visit, complete with attractive arched roofs and beautiful stained glass windows. Quiet, peaceful, get away from it all park Exclusive caravan park Grandchildren allowed Park Information Season: 10.5 month season Connection fee: POA Site fee: £2500 inc water Rates: POA Other Charges: Gas piped, Electric metered, water included Call today to view this holiday park. -

The Caernarfonshire Eagles: Development of a Traditional Emblem and County Flag

The Association of British Counties The Caernarfonshire Eagles: Development of a Traditional Emblem and County Flag by Philip S. Tibbetts & Jason Saber - 2 - Contents Essay.......................................................................................................................................................3 Appendix: Timeline..............................................................................................................................16 Bibliography Books.......................................................................................................................................17 Internet....................................................................................................................................18 List of Illustrations Maredudd ap Ieuan ap Robert Memorial..............................................................................................4 Wynn of Gwydir Monument.................................................................................................................4 Blayney Room Carving...........................................................................................................................5 Scott-Giles Illustration of Caernarfonshire Device.................................................................................8 Cigarette Card Illustration of Caernarvon Device..................................................................................8 Caernarfonshire Police Constabulary Helmet Plate...............................................................................9 -

51B Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

51B bus time schedule & line map 51B Denbigh View In Website Mode The 51B bus line (Denbigh) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Denbigh: 5:25 AM - 9:00 PM (2) Rhyl: 6:16 AM - 10:22 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 51B bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 51B bus arriving. Direction: Denbigh 51B bus Time Schedule 46 stops Denbigh Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:25 AM - 9:00 PM Bus Station, Rhyl 8 Kinmel Street, Rhyl Tuesday 5:25 AM - 9:00 PM Llys Glan Aber, Rhyl Wednesday 5:25 AM - 9:00 PM 89 Vale Road, Rhyl Thursday 5:25 AM - 9:00 PM Pendyffryn Road, Rhyl Friday 5:25 AM - 9:00 PM Trellewelyn Road, Rhyl Saturday 5:25 AM - 9:00 PM Llys Morgan, Rhyl Tower Gardens, Rhyl North Drive, Rhyl 51B bus Info The Boulevard, Rhyl Direction: Denbigh Stops: 46 Derwen Hotel, Rhyl Trip Duration: 51 min 166 Rhuddlan Road, Rhyl Community Line Summary: Bus Station, Rhyl, Llys Glan Aber, Rhyl, Pendyffryn Road, Rhyl, Llys Morgan, Rhyl, Clwyd Retail Park, Rhyl Tower Gardens, Rhyl, The Boulevard, Rhyl, Derwen Hotel, Rhyl, Clwyd Retail Park, Rhyl, Bryn Cwybr, Bryn Cwybr, Rhuddlan Rhuddlan, Highland Close, Rhuddlan, Maes Y Bryn, Pen-Y-Ffordd, Haulfre, Pen-Y-Ffordd, Treetops Court, Highland Close, Rhuddlan Rhuddlan, Parliament House, Rhuddlan, Marsh Warden, Rhuddlan, College, Pengwern, Bryn Carrog Maes Y Bryn, Pen-Y-Ffordd Farm, Bodelwyddan, Glan Clwyd Hospital, Fairlands Crescent, Rhuddlan Community Bodelwyddan, Vicarage Close, Bodelwyddan, Lowther Arms, Bodelwyddan, Business -

Bathafarn and Llanbedr Estate Records, (GB 0210 BATEDR)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Bathafarn and Llanbedr Estate Records, (GB 0210 BATEDR) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH This description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) Second Edition; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/bathafarn-and-llanbedr-estate-records-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/bathafarn-and-llanbedr-estate-records-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Bathafarn and Llanbedr Estate Records, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Industrial/Warehouse Premises Phoenix House London Road Corwen, Ll21 0Dr

29 Russell Road, Rhyl, Denbighshire, LL18 3BS Tel: 01745 330077 www.garethwilliams.co.uk Also as Beresford Adams Commercial 7 Grosvenor Street, Chester, CH1 2DD Tel: 01244 351212 www.bacommercial.com INDUSTRIAL/WAREHOUSE PREMISES PHOENIX HOUSE LONDON ROAD CORWEN, LL21 0DR FOR SALE/MAY LET Industrial/Development Opportunity Possible Development Site 616.08 sq m (6,631 sq ft) Commercial & Industrial Agents, Development, Investment & Management Surveyors LOCATION LEASE Corwen is a small historic and agriculturally The property will be available on the basis of a based town lying on the south bank of the River Full Repairing & Insuring lease for a length of Dee, and the southerly end of the County of term to be determined to include regular rent Denbighshire. reviews. The town is formed around the A5 PURCHASE PRICE London/Holyhead Trunk Road being some 30 Alternatively the property is available to miles to the south west of the City of Chester, purchase at £159,500. 20 miles to the west of Wrexham, 11 miles from Llangollen and 10 miles from Bala. RATES The VOA website confirms the property has a Phoenix House is located just off London Road, Rateable Value of £11,250. which is prime route through Corwen, from Llangollen, in a mixed commercial/residential For further information interested parties are environment. advised to contact the Local Rating Authority, Denbighshire County Council. Please refer to location plan. SERVICES DESCRIPTION All main services are available or connected to The building is situated on a sloping site at the the property subject to statutory regulations. front, which has been levelled to the rear. -

Four Stables Together with 2.3 Acres Or Thereabouts Of

FOUR STABLES TOGETHER WITH 2.3 ACRES OR THEREABOUTS OF LAND GARTH Y DWR GLYNDYFRDWY CORWEN DENBIGHSHIRE LL21 9HL 2.3 ACRES OR THEREABOUTS OF LAND SPLIT INTO THREE CONVENIENTLY SIZED PADDOCKS TO LET AS ONE LOT. AVAILABLE ON A COMMON LAW TENANCY FOR GRAZING BY HORSES AND PONIES. AVAILABLE FOR GRAZING BY HORSES OR PONIES THAT ARE USED SOLELY FOR RECREATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY. OPEN TO OFFERS, LAND TO BE LET PRIVATELY. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ALL ENQUIRIES TO Jones Peckover c/o Sarah Vaughan Williams BSc (Hons) Britannia House Pentraeth Road Four Crosses Menai Bridge Anglesey LL59 5RW Tel: 01248 362 524 AGENT’S REMARKS We have been instructed to offer approximately 2.3 acres of good grazing land, split into three conveniently sized paddocks along with four well-presented stables to let as one lot. SITUATION The land and stables are situated in a rural location near the village of Glyndyfrdwy, approximately 5 miles from Llangollen and 5 miles or thereabouts from Corwen. It is within close proximity to the A5 Trunk road and the city of Wrexham is only 16 miles or thereabouts from Garth y Dwr. DIRECTIONS From the town of Llangollen travel along the A5 towards Corwen for approximately 4.9 miles before turning right, down a lane signposted by a no through road sign. Travel along this road for 0.6 of a mile and you will reach Garth y Dwr, the last property along the lane. COMMON LAW TENANCY FOR GRAZING BY HORSES AND PONIES – MAIN HEADS OF TERMS Term The land will be let on a Common Law Tenancy for Grazing by Horses and Ponies. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

Plas Yolyn Estate Records and Manuscripts, (GB 0210 PLASYOLYN)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Plas Yolyn Estate Records and Manuscripts, (GB 0210 PLASYOLYN) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH This description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) Second Edition; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/plas-yolyn-estate-records-and- manuscripts archives.library .wales/index.php/plas-yolyn-estate-records-and-manuscripts Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Plas Yolyn Estate Records and Manuscripts, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................