Media Representations of the Iwing Oil Refinery Strike 1994-1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cenovus Reports Second-Quarter 2020 Results Company Captures Value by Leveraging Flexibility of Its Operations Calgary, Alberta (July 23, 2020) – Cenovus Energy Inc

Cenovus reports second-quarter 2020 results Company captures value by leveraging flexibility of its operations Calgary, Alberta (July 23, 2020) – Cenovus Energy Inc. (TSX: CVE) (NYSE: CVE) remained focused on financial resilience in the second quarter of 2020 and used the flexibility of its assets and marketing strategy to adapt quickly to the changing external environment. This positioned the company to weather the sharp decline in benchmark crude oil prices in April by reducing volumes at its oil sands operations and storing the mobilized oil in its reservoirs for production in an improved price environment. While Cenovus’s financial results were impacted by the weak prices early in the quarter, the company captured value by quickly ramping up production when Western Canadian Select (WCS) prices increased almost tenfold from April to an average of C$46.03 per barrel (bbl) in June. As a result of this decision, Cenovus reached record volumes at its Christina Lake oil sands project in June and achieved free funds flow for the month of more than $290 million. “We view the second quarter as a period of transition, with April as the low point of the downturn and the first signs of recovery taking hold in May and June,” said Alex Pourbaix, Cenovus President & Chief Executive Officer. “That said, we expect the commodity price environment to remain volatile for some time. We believe the flexibility of our assets and our low cost structure position us to withstand a continued period of low prices if necessary. And we’re ready to play a significant -

The 2021 “Irving Oil Fill-Up on Rewards” Digital Game - Official Rules

THE 2021 “IRVING OIL FILL-UP ON REWARDS” DIGITAL GAME - OFFICIAL RULES The "Irving Oil Fill-up on Rewards Digital Game” (the "Digital Game") is offered by Irving Oil Marketing, G.P. in Canada ("Irving Oil") and is administered by WSP International Limited ("Administrators"). Irving hereinafter will be referred to as the "Game Sponsor". NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO PLAY. Making a purchase will not improve your chances of winning. General Game Information: The Digital Game is being played at approximately 147 participating Irving Oil locations (“Participating Locations”) that accept the Irving Rewards Card and are located in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec only. The Digital Game is played using Digital Game Tickets (“Digital ticket(s)” that can be opened on a computer, tablet or smartphone. You may obtain a Digital ticket while supplies last, when you make any fuel purchase (any fuel type) at any Participating Location using your Irving Rewards card (“Qualifying Transaction”), at any time throughout The Digital Game Period, (as detailed below in Rule 1). You must have a registered Irving Rewards card in order to play and win prizes in the Digital Game. If you do not have an Irving Rewards card, pick one up free of charge at any Participating Location. There is no purchase or fee required to register your Irving Rewards card. To register your Irving Rewards card, go to www.irvingoil.com. Please allow up to seven (7) days from the day that you register your new Irving Rewards card to be eligible to receive Digital Game tickets. You can obtain a Digital ticket without making a purchase by sending a 3” x 5” card legibly printed with your name, your Irving Rewards number and your email address, to "Irving Fill-up On Rewards Digital Ticket Request, P.O. -

Provincial Solidarities: a History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour

provincial solidarities Working Canadians: Books from the cclh Series editors: Alvin Finkel and Greg Kealey The Canadian Committee on Labour History is Canada’s organization of historians and other scholars interested in the study of the lives and struggles of working people throughout Canada’s past. Since 1976, the cclh has published Labour / Le Travail, Canada’s pre-eminent scholarly journal of labour studies. It also publishes books, now in conjunction with AU Press, that focus on the history of Canada’s working people and their organizations. The emphasis in this series is on materials that are accessible to labour audiences as well as university audiences rather than simply on scholarly studies in the labour area. This includes documentary collections, oral histories, autobiographies, biographies, and provincial and local labour movement histories with a popular bent. series titles Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist Bert Whyte, edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Working People in Alberta: A History Alvin Finkel, with contributions by Jason Foster, Winston Gereluk, Jennifer Kelly and Dan Cui, James Muir, Joan Schiebelbein, Jim Selby, and Eric Strikwerda Union Power: Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage The Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929–39 Eric Strikwerda Provincial Solidarities: A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour / Solidarités provinciales: Histoire de la Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Nouveau-Brunswick David Frank A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour david fra nk canadian committee on labour history Copyright © 2013 David Frank Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, ab t5j 3s8 isbn 978-1-927356-23-4 (print) 978-1-927356-24-1 (pdf) 978-1-927356-25-8 (epub) A volume in Working Canadians: Books from the cclh issn 1925-1831 (print) 1925-184x (digital) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. -

New Book on Irving Oil Explores Business

New book on Irving Oil explores business Miramichi Leader (Print Edition)·Nathalie Sturgeon CA|September 25, 2020·08:00am Section: B·Page: B6 SAINT JOHN • New Brunswick scholar and author Donald J. Savoie has published a new book exploring the origins of the Irving Oil empire. Savoie, who is the Canada Research Chair in Public Administration and Governance at the Université de Moncton, has released Thanks for the Business: Arthur L. Irving, K.C. Irving and the Story of Irving Oil. It’s look at entrepreneurship through the story of this prominent Maritime business family. “New Brunswickers, and Maritimers more generally, should applaud business success,” said Savoie, who describes himself as a friend of Arthur Irving. “We haven’t had a strong record of applauding business success. I think K.C. Irving, Arthur Irving, and Irving Oil speak to business success.” Irving Oil is the David in a David and Goliath story of major oil refineries in the world, Savoie noted, adding it provides a valuable economic contribution to the province as a whole, having laid the in-roads within New Brunswick into a multi-country oil business. He wanted his book to serve as a reminder of that. In a statement, Candice MacLean, a spokeswoman for Irving Oil, said company employees are proud to read the story of K.C. Irving, the company’s founder, and Arthur Irving, the company’s current chairman. “(Arthur’s) passion and love for the business inspires all of us every day,” MacLean said. “Mr Savoie’s Thanks for the Business captures the story of the Irving Oil that we are proud to be a part of.” In his new book, Savoie, who has won the Donner Prize for public policy writing, details Irving Oil’s “success born in Bouctouche and grown from Saint John, New Brunswick.” The company now operates Canada’s largest refinery, along with more than 900 gas stations spanning eastern Canada and New England, according to Savoie. -

An Effects-Based Assessment of the Health of Fish in a Small Estuarine Stream Receiving Effluent from an Oil Refinery

An effects-based assessment of the health of fish in a small estuarine stream receiving effluent from an oil refinery by Geneviève Vallières B.Sc. Biology, Université de Sherbrooke, 1998 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science In the Graduate Academic Unit of Biology Supervisors: Kelly Munkittrick, Ph.D. Department of Biology Deborah MacLatchy, PhD. Department of Biology Examining Board: Kenneth Sollows, Ph.D., Department of Engineering, Chair Simon Courtenay, Ph. D. Department of Biology External Examiner: Kenneth Sollows, Ph.D., Department of Engineering This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate studies. THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK May, 2005 © Geneviève Vallières, 2005 ABSTRACT A large oil refinery discharges its effluent into Little River, a small estuarine stream entering Saint John Harbour. An effects-based approach was used to assess the potential effects of the oil refinery effluent on fish and fish habitat. The study included a fish community survey, a sentinel species survey, a fish caging experiment, and a water quality survey. The study showed that the fish community and the sentinel species, the mummichog (Fundulus heteroclitus), were impacted in the stream receiving the oil refinery effluent. Lower abundance and species richness were found downstream of the effluent discharge whereas increased liversomatic index and MFO (females only) were measured in fish collected in Little River. Water quality surveys demonstrated that the receiving environment is subjected to extended periods of low dissolved oxygen levels downstream of the effluent discharge. The anoxic periods correlated with the discharge of ballast water through the waste treatment system. -

Supply Chain Excellence – from Refinery to Market Jet Fuel

Jet fuel Supply chain excellence – from refinery to market For decades we’ve been making products that exceed manufacturer and environmental regulations. We focus on building trusting relationships by providing quality products, a safe, reliable supply and responding to your needs quickly and respectfully. Supply chain excellence A team on your side Three quick questions • Best practices – We have been • Customer focus – Our commitment to get us started fuelling commercial airlines, to you is a part of who we are as military aircraft, cargo carriers a company. Since 1924, customer 1. Which locations do you travel and corporate fleets for more than focus has been one of our guiding to? 40 years. As an IATA Strategic principles. Partner, we practice the policies and 2. Will you require hangar space procedures that have revolutionized • People you trust – Our mobile team on arrival? understands the market, provides aviation standards. 3. What is your annual volume and technical support and is dedicated fleet size? • Reliable supply – From our state-of- to serving you. At our three FBOs the-art refinery in Saint John, NB, in Gander, St. John’s or Goose Bay, Customer support a dedicated fleet of truck, rail and Newfoundland, expect service with a marine vessels deliver jet fuel to 20 smile in addition to jet fuel. Call us at 1.866.865.8800 or email plus airports in Atlantic Canada and [email protected] New England. • Customer support – We have a Customer Support Team available to We look forward to serving you. take care of your needs. The products you need • Quality products – We produce A focus on quality and deliver jet fuel that meets • Quality focus – We test all raw CAN/CGSB-3.23 and ASTM D-1655 materials and finished products to specifications. -

Team Effort at IPP • Working on the Largest Building in NB • • Alt Hotel • Shipping Steel to Texas (Then Peru) • Recognition Dinner • Pg.6 Pg.19 Pg.31

fall & winter 2013 The biannual newsmagazine of t he OSCO Construction Group OSCO construction group • Team Effort at IPP • Working on the Largest Building in NB • • Alt Hotel • Shipping Steel to Texas (then Peru) • Recognition Dinner • pg.6 pg.19 pg.31 What’s Inside... fall & winter 2013 3 Message from the President 30 Harbour Bridge Refurbishment, Saint John, NB priorities profiles 31 Group Safety News 21 Customer Profile: Erland Construction 32 OSCO Environmental Management System 24 Product Profile: Precast Infrastructure 33` Information Corner 33 Sackville Facility Renovations public & community 34 Touch a Truck projects 34 NSCC Foundation Bursary Award 4 Irving Pulp & Paper, Saint John, NB 35 Steel Day 6 Kent Distribution Centre, Moncton, NB 35 National Precast Day 8 Alt Hotel, Halifax, NS 36 Pte. David Greenslade Peace Park 9 Non-Reactive Stone at OSCO Aggregates 10 South Beach Psychiatric Center, Staten Island, NY people 11 Irving Big Stop, Enfield, NS 37 Event Planning Committees 12 Lake Utopia Paper, Lake Utopia, NB 37 OSCO Group Bursary Winners 14 Irving Oil Refinery, Saint John, NB 38 Employee Recognition Dinner 16 Jasper Wyman & Son Blueberries, Charlottetown, PE 40 OSCO Golf Challenge 17 Shipping Steel to Texas (& Peru) 40 Retirement Lane Gary Bogle, Gary Fillmore, Roland Froude, Raymond Goguen, Joyce 18 Rebar, misc. projects Murray, Raymond Price, Dale Smith, Brian Underwood, Alfred Ward 19 Pier 8 & Fairview Cove Caissons, Halifax, NS 42 National Safety Award for Strescon 20 3rd Avenue, Burlington, MA 42 Group Picnic 22 Miscellaneous Metals Division, update 43 Fresh Faces 22 Ravine Centre II, Halifax, NS 43 Wall of Fame 23 Hermanville Wind Farm, Hermanville, PE 43 Congratulations 29 Cape Breton University, Cape Breton, NS 44 Our Locations OSCO 29 Regent Street Redevelopment, Fredericton, NB construction 30 DND Explosive Storage Facility, Halifax, NS group CONNECTIONS is the biannual magazine of the OSCO on our cover.. -

2020 Annual Report & Annual General Meeting

Stuart House Bed Thank you to all of our generous 2020 Community Partners & Breakfast Subway 2020 Annual Report & NB Museum Sussex Wellness NBCC Network Saint John Nick Nicolle TD Wealth Mitsubishi Community Centre Teed Saunders Annual General Meeting Staff Norm & Donna Doyle & Co. Teen Resource Centre participating Michaelsen Olofsfors Inc. Thandi Restaurant George Hitchcock Award in Dress P.R.O. Kids The Big 50/50 Meeting Agenda: Down for a PALS Program The Boys and Girls Vision recipients: Pathways to Education Club of Saint John Tuesday, June 15, 2021 Big Cause, Peter Coughlan – The Chocolate Museum All young Seth Parsons Iesha Severin The NB Box February Exit Realty people 1. Call to Order & Acknowledgements PFLAG The Promise Partnership 2020. Board President, Niki Comeau Pierce Atwood LLP The Saint John realize their Pristine Multicultural Minute of Silence for children of residential Project Roar and Newcomers full potential schools Past President, Debbie Cooper Resource Centre Quispamsis Middle School 2. Chairperson and Secretary Named Acadia Broadcasting Cindy Millett Hughes Surveys and RBC Foundation Tim Hortons – Advocate Printing City of Saint John Consultants Inc. RBC Future Launch Murphy Restaurants Niki Comeau Air Canada Foundation Commercial Properties Huntsman Marine Richard Alderman Ltd. 3. Meeting Duly Constituted Timbertop Adventures Al Gagnon Photography Compass Education Aquarium Rockwood Park (Reading Notice of Meeting) ALPA Equipment Support Program ICS Creative Agency Touchstone Academy Rogers TV Executive Director, Laurie Collins Company Connors Bros. IG Wealth – Team Rogue Coffee Town of Hampton Anglophone South Cooke Aquaculture Larry Clark Rossmount Inn Town of St. George 4. Quorum (1/3 of Board Members: 5) School District Cox & Palmer Imperial Theatre Rotary Club of Town of St. -

50223 Service Date – May 4, 2020 Eb Surface Transportation

50223 SERVICE DATE – MAY 4, 2020 EB SURFACE TRANSPORTATION BOARD DECISION Docket No. FD 36368 SOO LINE CORPORATION—CONTROL— CENTRAIL MAINE & QUEBEC RAILWAY US INC. Decision No. 3 Digest:1 This decision authorizes Soo Line Corporation to acquire control of Central Maine & Quebec Railway US Inc. Decided: May 1, 2020 On December 17, 2019, Soo Line Corporation (Soo Line Corp.) and Central Maine & Quebec Railway US Inc. (CMQR US) (collectively, Applicants) filed an application seeking Board approval for Soo Line Corp. to acquire control of CMQR US. This proposal is referred to as the Transaction. The Board approves the application, subject to standard employee protective conditions. BACKGROUND Applicants seek the Board’s prior review and authorization pursuant to 49 U.S.C. §§ 11323-25 and 49 C.F.R. part 1180 for Soo Line Corp. to acquire control of CMQR US. (Appl. 1.) Applicant Soo Line Corp. is an indirect, wholly owned subsidiary of Canadian Pacific Railway Company (CP). (Id. at 1 n.1.) Applicant CMQR US is a wholly owned subsidiary of Railroad Acquisition Holdings LLC (RAH). (Id. at 1, 6.) RAH is a wholly owned subsidiary of Fortress Transportation and Infrastructure Investors LLC. (Id. at 1 n.2.) Soo Line Corp. plans to acquire all of the outstanding membership interests of RAH, including all of the outstanding common stock of CMQR US, through a merger of Black Bear Acquisition LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Soo Line Corp., and RAH, pursuant to an Agreement and Plan of Merger. (Id. at 6.) RAH would be the surviving limited liability company and a wholly owned subsidiary of Soo Line Corp. -

The Ordnance Building: Rejeuvenated SJ Military Landmark Celebrates Grand Re-Opening

spring & summer 2011 The biannual newsmagazine of t he OSCO Construction Group The Ordnance Building: Rejeuvenated SJ Military Landmark Celebrates Grand Re-Opening Stretch Program • Steel Bridges • UNBSJ • Stormceptor • Nugget Pond Milling Facility • Recruitment Initiatives • 25 Year Club pg.8 pg.17 pg.37 What’s Inside... spring & summer 2011 3 Message from the President 28 Picadilly Update 30 York Miscellaneous Metals Updates priorities 31 FCC Takes on Electrical & Cabling Contract for New Data Centre 4 Safety: Stretch Program 31 Saint John Interchange 5 Group Safety News 6 Quality Control Updates profiles 7 Environment: Greening Our Precast Processes 20 Customer Profile: PCL projects public & community 8 Ocean Steel Bridges the Gap 36 Helping Hands Penniac Bridge & McAdam Railway Line 36 Habitat for Humanity 10 Newly Restored Landmark Opens its Doors OSCO Concrete donates ready-mix for Rothesay home FCC Construction wraps up work on The Ordnance Building 36 Take Our Kids to Work Day 12 Bins, Chutes & Ducts Ocean Steel dedicating more resources to growing structural platework 37 Building Futures in Uganda market Ocean Steel shop electrician takes an eye-opening journey to Uganda 13 UNBSJ OSCO Group leaves its mark on local university campus people 14 Pipe Division Update: Profile on Stormceptor 32 25 Year Club Dinner 14 Wing Greenwood Healthcare Facility; Point Pleasant Park; Memorial University Parking Garage; Goose Bay Airport 33 OSCORS Employee Recognition Dinner 16 IOR Energy & Utilities Maintenance Facility 34 Recruitment Initiatives -

Saint John YMCA • Maritime Ontario • Bath Iron Works • 45 Stuart St. First

connections the biannual newsmagazine of the OSCO Construction Group fall & winter 2014 Saint John YMCA • Maritime Ontario • Bath Iron Works • 45 Stuart St. First 2000 NEBT Girders in Maritimes • Cabela’s • Floating Concrete the biannual newsmagazine of fall & winter 2014 connections the OSCO Construction Group what’s inside projects 4 .....Saint John YMCA 16 ...Cabela’s 22 ...Icon Bay Tower 6 .....Maritime Ontario 17.... Harbour Isle 22 ... Miscellaneous 8 .....Bath Iron Works Hazelton Metals Division 9 .....45 Stuart Street 17....Mr. Lube 23 ...Spryfield Bridge 18 ... Marine Terminal 24 ...Floating Concrete 10 ...Irving Oil Refinery 3 ..... Message from Projects 14 ... Fire Training 24 ...Scotia Wind Farms the President 20 ... Misc Rebar Projects Structure 25 ... The Bend Radio 52 ...Our Locations 14 ...Starfish Properties 20 ...Food Station 15 ... First 2000 NEBT 21 ...Bell Aliant 30 ... Wood Islands Girders in Maritimes 22 ...Varners Bridge Wharf profiles priorities 12 ... Product: Staggered Truss Framing (Summer House) 31 ... Safety: Safety Awards & Strescon Pipe Plant Milestone 26 ... Product: Precast Parking Garages 32 ... Technology: Summerside Plant Renovations 33 ...Technology: Best Nests 36 ... Environment: Restoring the landscape 37 ... Environment: e-waste people 41 ...Communication: Information Corner 42 ... OSCO Announces 41 ...Communication: Email sign up Promotions 44 ... Employee Appreciation Celebration 47 ... Employee Recognition Program public & 48 ...Retirement Lane community 49 ...Group Picnic 50 ...Group Golf Tournament 38 ...Saint John Touch a Truck 50 ... Strescon Golf 38 ...OSCO Bursary Winners Tournament 38 ...Steel Day 51 ...Fresh Faces 38 ...NSCC Foundation Bursary 51 ...Congratulations 39 ... Pte. David Greenslade Bursary & Park 39 ...Special Olympics 40...OSCO Group Career Fair OSCO 40...Employer of the Year construction group CONNECTIONS is the biannual magazine of the OSCO on our cover.. -

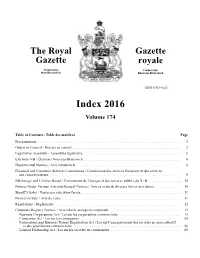

The Royal Gazette Index 2016

The Royal Gazette Gazette royale Fredericton Fredericton New Brunswick Nouveau-Brunswick ISSN 0703-8623 Index 2016 Volume 174 Table of Contents / Table des matières Page Proclamations . 2 Orders in Council / Décrets en conseil . 2 Legislative Assembly / Assemblée législative. 6 Elections NB / Élections Nouveau-Brunswick . 6 Departmental Notices / Avis ministériels. 6 Financial and Consumer Services Commission / Commission des services financiers et des services aux consommateurs . 9 NB Energy and Utilities Board / Commission de l’énergie et des services publics du N.-B. 10 Notices Under Various Acts and General Notices / Avis en vertu de diverses lois et avis divers . 10 Sheriff’s Sales / Ventes par exécution forcée. 11 Notices of Sale / Avis de vente . 11 Regulations / Règlements . 12 Corporate Registry Notices / Avis relatifs au registre corporatif . 13 Business Corporations Act / Loi sur les corporations commerciales . 13 Companies Act / Loi sur les compagnies . 54 Partnerships and Business Names Registration Act / Loi sur l’enregistrement des sociétés en nom collectif et des appellations commerciales . 56 Limited Partnership Act / Loi sur les sociétés en commandite . 89 2016 Index Proclamations Lagacé-Melanson, Micheline—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Acts / Lois Saulnier, Daniel—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Therrien, Michel—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Credit Unions Act, An Act to Amend the / Caisses populaires, Loi modifiant la Loi sur les—OIC/DC 2016-113—p. 837 (July 13 juillet) College of Physicians and Surgeons of New Brunswick / Collège des médecins Energy and Utilities Board Act / Commission de l’énergie et des services et chirurgiens du Nouveau-Brunswick publics, Loi sur la—OIC/DC 2016-48—p.