Site Report: Potamac Ave and AX204

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

2E – Four Mile

City of Alexandria, Virginia Geologic Atlas of the City of Alexandria, Virginia and Vicinity – Plate 2E NW E GEOLOGIC CROSS SECTION E’ SE FEET NORTHWEST FEET Claremont FOUR MILE RUN 200 GT-112 200 191 Tcg by Anthony H. Fleming, 2015 173 Kpl Barcroft Kpb Park 150 151 150 Kpcv 89 Kpcc Kpcs 100 100 Qc Lucky BEVERLEY HILLS Reservoir Qs Run Charles Kpcg Qaf SHIRLEY HWY Barrett Woods Qa QUAKER LANE MOUNT IDA J-1 60 School 63 GT-42 55 GT-85 GT-185 Shirlington GT-62 50 Qa 48 50 47 POTOMAC YARDS 50 GT-68 GT-67 Qto Qcf Qt 45 44 Qt Arlandria Qcf 39 38 Qa 39 38 Four Mile Rte 1 GT-4 Qcf 30 31 32 Hume Lynhaven 30 Kpcc 30 28 s Qt 25 Run Park GT-136 Qcf Spring GT-117 OCi Kpcv Qto 20 17 15 F-3 Kpcv 16 af 11 Qto af Qa af Qto Kpcs Kpcc Kpcc Kpch Qs Qt 3 SL 0 Qe SL -3 -7 ? Qal Qto-c Kpcc org -25 95% sand org Qto-c -38 -50 Kpch? -50 Kpcc Kpcc 58% total sand (96/164) -68 OCI Kpcs -100 Ogu -100 35% sand Kpcv? -120 Kpcc -150 -149 -150 OCs Kpcs? -200 -195 -200 RCSZ -250 -250 -300 -300 SEE PLATE 5 FOR EXPLANATION OF MAP UNITS VERTICAL EXAGGERATION 20X 1000 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 8000 9000 10000 FEET EXPLANATION OF CROSS SECTION SYMBOLS: WATER WELL GEOTECHNICAL BORING SITES WATER LEVELS REPORTED IN WELLS OTHER SYMBOLS J-60 WELL ID NUMBER AND SURFACE ELEVATION GT-27 ID NUMBER AND HIGHEST AND GEOTECHNICAL BORINGS 250 222 (SOURCE: J-JOHNSTON; D-DARTON; F-FROELICH) SURFACE ELEVATION 47 SURFACE EXPOSURE. -

Bladensburg Prehistoric Background

Environmental Background and Native American Context for Bladensburg and the Anacostia River Carol A. Ebright (April 2011) Environmental Setting Bladensburg lies along the east bank of the Anacostia River at the confluence of the Northeast Branch and Northwest Branch of this stream. Formerly known as the East Branch of the Potomac River, the Anacostia River is the northernmost tidal tributary of the Potomac River. The Anacostia River has incised a pronounced valley into the Glen Burnie Rolling Uplands, within the embayed section of the Western Shore Coastal Plain physiographic province (Reger and Cleaves 2008). Quaternary and Tertiary stream terraces, and adjoining uplands provided well drained living surfaces for humans during prehistoric and historic times. The uplands rise as much as 300 feet above the water. The Anacostia River drainage system flows southwestward, roughly parallel to the Fall Line, entering the Potomac River on the east side of Washington, within the District of Columbia boundaries (Figure 1). Thin Coastal Plain strata meet the Piedmont bedrock at the Fall Line, approximately at Rock Creek in the District of Columbia, but thicken to more than 1,000 feet on the east side of the Anacostia River (Froelich and Hack 1975). Terraces of Quaternary age are well-developed in the Bladensburg vicinity (Glaser 2003), occurring under Kenilworth Avenue and Baltimore Avenue. The main stem of the Anacostia River lies in the Coastal Plain, but its Northwest Branch headwaters penetrate the inter-fingered boundary of the Piedmont province, and provided ready access to the lithic resources of the heavily metamorphosed interior foothills to the west. -

UPPER SHENANDOAH RIVER BASIN Drought Preparedness and Response Plan

UPPER SHENANDOAH RIVER BASIN Drought Preparedness and Response Plan Prepared by Updated June 2012 Upper Shenandoah River Basin Drought Preparedness and Response Plan (This page intentionally left blank) June 2011 Page 2 Upper Shenandoah River Basin Drought Preparedness and Response Plan Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction................................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Historical Background .................................................................................................................. 6 3.0 Drought Response Stage Declaration, Implementation and Response Measures.......................... 8 Drought Declaration .................................................................................................................... 10 Drought Indicators ....................................................................................................................... 10 Drought Response Stages and Response Measures ..................................................................... 10 4.0 Drought Response Stage Termination .......................................................................................... 11 5.0 Plan Revisions ............................................................................................................................... 11 Appendix A Locality Drought Watch, Warning and Emergency Indicators Appendix B Drought Watch Responses and Water Conservation Measures Appendix C Drought Warning Responses -

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Northern Neck Land Proprietary Records

The Virginia government always held legal jurisdiction over the area owned by the proprietary, so all court actions are found within the records of the counties that comprised it. The Library holds local records such Research Notes Number 23 as deeds, wills, orders, loose papers, and tax records of these counties, and many of these are on microfilm and available for interlibrary loan. Researchers will find that the proprietary records provide a unique doc- umentary supplement to the extant records of this region. The history of Virginia has been enriched by their survival. Northern Neck Land Proprietary Records Introduction The records of the Virginia Land Office are a vital source of information for persons involved in genealog- ical and historical research. Many of these records are discussed in Research Notes Number 20, The Virginia Land Office. Not discussed are the equally rich and important records of the Northern Neck Land Proprietary, also known as the Fairfax Land Proprietary. While these records are now part of the Virginia Land Office, they were for more than a century the archive of a vast private land office owned and oper- ated by the Fairfax family. The lands controlled by the family comprised an area bounded by the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers and stretched from the Chesapeake Bay to what is now West Virginia. It embraced all or part of the cur- rent Virginia counties and cities of Alexandria, Arlington, Augusta, Clarke, Culpeper, Fairfax, Fauquier, Frederick, Greene, King George, Lancaster, Loudoun, Madison, Northumberland, Orange, Page, Prince William, Rappahannock, Shenandoah, Stafford, Warren, Westmoreland, and Winchester, and the current West Virginia counties of Berkeley, Hampshire, Hardy, Jefferson, and Morgan. -

State Water Control Board Page 1 O F16 9 Vac 25-260-350 and 400 Water Quality Standards

STATE WATER CONTROL BOARD PAGE 1 O F16 9 VAC 25-260-350 AND 400 WATER QUALITY STANDARDS 9 VAC 25-260-350 Designation of nutrient enriched waters. A. The following state waters are hereby designated as "nutrient enriched waters": * 1. Smith Mountain Lake and all tributaries of the impoundment upstream to their headwaters; 2. Lake Chesdin from its dam upstream to where the Route 360 bridge (Goodes Bridge) crosses the Appomattox River, including all tributaries to their headwaters that enter between the dam and the Route 360 bridge; 3. South Fork Rivanna Reservoir and all tributaries of the impoundment upstream to their headwaters; 4. New River and its tributaries, except Peak Creek above Interstate 81, from Claytor Dam upstream to Big Reed Island Creek (Claytor Lake); 5. Peak Creek from its headwaters to its mouth (confluence with Claytor Lake), including all tributaries to their headwaters; 6. Aquia Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 7. Fourmile Run from its headwaters to the state line; 8. Hunting Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 9. Little Hunting Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 10. Gunston Cove from its headwaters to the state line; 11. Belmont and Occoquan Bays from their headwaters to the state line; 12. Potomac Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 13. Neabsco Creek from its headwaters to the state line; 14. Williams Creek from its headwaters to its confluence with Upper Machodoc Creek; 15. Tidal freshwater Rappahannock River from the fall line to Buoy 44, near Leedstown, Virginia, including all tributaries to their headwaters that enter the tidal freshwater Rappahannock River; 16. -

Authorization to Discharge Under the Virginia Stormwater Management Program and the Virginia Stormwater Management Act

COMMONWEALTHof VIRGINIA DEPARTMENTOFENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Permit No.: VA0088587 Effective Date: April 1, 2015 Expiration Date: March 31, 2020 AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE VIRGINIA STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PROGRAM AND THE VIRGINIA STORMWATER MANAGEMENT ACT Pursuant to the Clean Water Act as amended and the Virginia Stormwater Management Act and regulations adopted pursuant thereto, the following owner is authorized to discharge in accordance with the effluent limitations, monitoring requirements, and other conditions set forth in this state permit. Permittee: Fairfax County Facility Name: Fairfax County Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System County Location: Fairfax County is 413.15 square miles in area and is bordered by the Potomac River to the East, the city of Alexandria and the county of Arlington to the North, the county of Loudoun to the West, and the county of Prince William to the South. The owner is authorized to discharge from municipal-owned storm sewer outfalls to the surface waters in the following watersheds: Watersheds: Stormwater from Fairfax County discharges into twenty-two 6lh order hydrologic units: Horsepen Run (PL18), Sugarland Run (PL21), Difficult Run (PL22), Potomac River- Nichols Run-Scott Run (PL23), Potomac River-Pimmit Run (PL24), Potomac River- Fourmile Run (PL25), Cameron Run (PL26), Dogue Creek (PL27), Potomac River-Little Hunting Creek (PL28), Pohick Creek (PL29), Accotink Creek (PL30),(Upper Bull Run (PL42), Middle Bull Run (PL44), Cub Run (PL45), Lower Bull Run (PL46), Occoquan River/Occoquan Reservoir (PL47), Occoquan River-Belmont Bay (PL48), Potomac River- Occoquan Bay (PL50) There are 15 major streams: Accotink Creek, Bull Run, Cameron Run (Hunting Creek), Cub Run, Difficult Run, Dogue Creek, Four Mile Run, Horsepen Run, Little Hunting Creek, Little Rocky Run, Occoquan Receiving Streams: River, Pimmit run, Pohick creek, Popes Head Creek, Sugarland Run, and various other minor streams. -

Shenandoah County Historic Resources Survey Report

sh-49 SIIBNANDOAH COUNTY HISTORIC RESOURCES SURVEY SURVEY REPORT IÈ May 1995 STMNANDOAH COUNTY HISTORIC RESOURCES SURVEY SURVEY REPORT Shirley Maxwell and James C. Massey Maral S. Kalbian Massey Maxwell Associates Preservation Consultant P. O. Box 263 Rr 1 Box 86, Boyce, VA 22620 Strasburg, VA 22657 (703) 837-2A81 (703) 646s-4s66 J. Daniel Pezzoni Preservation Technologies, Inc. PO Box 7825, Roanoke, YA 24019 (703) 342-7832 written by James C. Massey, Shirley Maxwell, J. Daniel Pezzoni, and Judy B. Reynolds with contibtttions by Maral S. Kalbian, Scott M. Hudlow, Susan E. Smead, and Marc C. Wagner, Jeffrey C. Everett, Geoffrey B. Henry, Nathaniel P. Neblett and Barbara M. Copp prepared for The Virginia Department of Historic Resources 221 Governor Street Richmond, VA 23219 (804) 786-3143 May 1995 L TABLE OF CONTENTS il. ABSTRACT .. I III. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 IV. LIST OF MAPS, LLUSTRATIONS, TABLES 2 V. DESCRIPTON OF PROJECT 5 VI. HISTORIC CONTEXT 7 Historic Overview 7 Topography and Political Organization of Shenandoah County 8 Prehistoric Native American Settlement: 10,000 B.C-1606 A.D. European Settlement to Society: 1607-1749 Colony to Nation: 1750-1789 10 Domestic Theme 14 Agriculture Theme 26 Education Theme . 36 Military Theme . 44 Retigionttreme... 48 Health Care and Recreation Theme 53 Transportation Theme 56 Commerce Theme 63 Industry Theme 67 Funerary Theme 76 Settlement and Ethnicity Theme 80 ArchitectureTheme... 82 Government/LadPolitical Theme . 106 Social Theme 106 Technology and Engineering Theme 106 The New Dominion: 1946-Present 106 VII. RESEARCH DESIGN . 107 VM. SURVEY FINDINGS 110 IX. EVALUATION . t12 X. RECOMMENDATIONS 122 XL BIBLIOGRAPHY 133 t_ {" XII. -

Shoreline Situation Report Stafford County, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1975 Shoreline Situation Report Stafford County, Virginia Carl H. Hobbs III Virginia Institute of Marine Science Gary F. Anderson Virginia Institute of Marine Science Dennis W. Owen Virginia Institute of Marine Science Peter Rosen Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Environmental Monitoring Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Hobbs, C. H., Anderson, G. F., Owen, D. W., & Rosen, P. (1975) Shoreline Situation Report Stafford County, Virginia. Special Report In Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 79. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V5PB01 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shoreline Situation Report ST AFFORD COUNTY, VIRGINIA Special Report In Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 79 Chesapeake Research Consortium Report Number 13 Supported by the National Science Foundation, Research Applied to National Needs Program NSF Grant Nos. GI 34869 and GI 38973 to the Chesapeake Research Consortium, Inc. Published With Funds Provided to the Commonwealth by the Office of Coastal Zone Management National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Grant No. 04-5-158-50001 VIRGINIA INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCE Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 1975 Shoreline Situation Report ST AFFORD COUNTY, VIRGINIA Special Report In Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 79 Chesapeake Research Consortium Report Number 13 Prepared by: Carl H. -

A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 "Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800 Wendy Sacket College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Sacket, Wendy, ""Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625418. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ypv2-mw79 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "PEOPLING THE WESTERN COUNTRY": A STUDY OF MIGRATION FROM AUGUSTA COUNTY, VIRGINIA, TO KENTUCKY, 1777-1800 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Wendy Ellen Sacket 1987 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, December, 1987 John/Se1by *JU Thad Tate ies Whittenburg i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................. iv LIST OF T A B L E S ...............................................v LIST OF MAPS . ............................................. vi ABSTRACT................................................... v i i CHAPTER I. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LITERATURE, PURPOSE, AND ORGANIZATION OF THE PRESENT STUDY . -

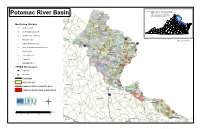

Potomac River Basin Assessment Overview

Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality PL01 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Potomac River Basin Virginia Geographic Information Network PL03 PL04 United States Geological Survey PL05 Winchester PL02 Monitoring Stations PL12 Clarke PL16 Ambient (120) Frederick Loudoun PL15 PL11 PL20 Ambient/Biological (60) PL19 PL14 PL23 PL08 PL21 Ambient/Fish Tissue (4) PL10 PL18 PL17 *# 495 Biological (20) Warren PL07 PL13 PL22 ¨¦§ PL09 PL24 draft; clb 060320 PL06 PL42 Falls ChurchArlington jk Citizen Monitoring (35) PL45 395 PL25 ¨¦§ 66 k ¨¦§ PL43 Other Non-Agency Monitoring (14) PL31 PL30 PL26 Alexandria PL44 PL46 WX Federal (23) PL32 Manassas Park Fairfax PL35 PL34 Manassas PL29 PL27 PL28 Fish Tissue (15) Fauquier PL47 PL33 PL41 ^ Trend (47) Rappahannock PL36 Prince William PL48 PL38 ! PL49 A VDH-BEACH (1) PL40 PL37 PL51 PL50 VPDES Dischargers PL52 PL39 @A PL53 Industrial PL55 PL56 @A Municipal Culpeper PL54 PL57 Interstate PL59 Stafford PL58 Watersheds PL63 Madison PL60 Impaired Rivers and Streams PL62 PL61 Fredericksburg PL64 Impaired Reservoirs or Estuaries King George PL65 Orange 95 ¨¦§ PL66 Spotsylvania PL67 PL74 PL69 Westmoreland PL70 « Albemarle PL68 Caroline PL71 Miles Louisa Essex 0 5 10 20 30 Richmond PL72 PL73 Northumberland Hanover King and Queen Fluvanna Goochland King William Frederick Clarke Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Loudoun Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Rappahannock River Basin