National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Popes Creek Trail Concept Presented

Popes Creek Trail concept presented Posted by TBN_Charles On 06/22/2017 La Plata, MD - The Pope’s Creek Rail Trail is moving forward. Eileen Minnick, Charles County director of recreation, told the Charles County Commissioners Tuesday, June 20 that barring any hiccups along the way, construction on the new trail could begin as early as next summer. In January 2014, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources was awarded a $1 million federal grant to preserve 220 acres of the Popes Creek watershed. The thought was to establish a new rail trail along the abandoned Popes Creek rail bed, a distance of some two miles. “One of the goals of the county recreation and parks and tourism is water access,” said Parks Director Jon Snow. “It’s a real challenge to get waterfront access.” Snow said the county is adding boat ramps and kayak launches at Port Tobacco River Park and Chapel Point. “Everyone in Charles County wants it, but not everyone is a boater,” Snow said. “But they still want water access. These projects will do a really good job of providing that. “Popes Creek is one of our best opportunities for waterfront access,” he added. “We’ve got a really good opportunity to create a water access venue on and off the water. Steve Engle of Vista Design Inc. outlined a conceptual plan for the trail, which includes an elevated observation platform over the Potomac River and a possible museum at the site of the old Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative power plant at Popes Creek, built in 1938. -

Key Facts About Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis Families

Key Facts about Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis families. The George Washington Foundation The Foundation owns and operates Ferry Farm and Historic Kenmore. The Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. The Foundation (then known as the Kenmore Association) was formed in 1922 in order to purchase Kenmore. The Foundation purchased Ferry Farm in 1996. Historic Kenmore Kenmore was built by Fielding Lewis and his wife, Betty Washington Lewis (George Washington’s sister). Fielding Lewis was a wealthy merchant, planter, and prominent member of the gentry in Fredericksburg. Construction of Kenmore started in 1769 and the family moved into their new home in the fall of 1775. Fielding Lewis' Fredericksburg plantation was once 1,270 acres in size. Today, the house sits on just one city block (approximately 3 acres). Kenmore is noted for its eighteenth-century, decorative plasterwork ceilings, created by a craftsman identified only as "The Stucco Man." In Fielding Lewis' time, the major crops on the plantation were corn and wheat. Fielding was not a major tobacco producer. When Fielding died in 1781, the property was willed to Fielding's first-born son, John. Betty remained on the plantation for another 14 years. The name "Kenmore" was first used by Samuel Gordon, who purchased the house and 200 acres in 1819. Kenmore was directly in the line of fire between opposing forces in the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862 during the Civil War and took at least seven cannonball hits. Kenmore was used as a field hospital for approximately three weeks during the Civil War Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. -

Native Vascular Flora of the City of Alexandria, Virginia

Native Vascular Flora City of Alexandria, Virginia Photo by Gary P. Fleming December 2015 Native Vascular Flora of the City of Alexandria, Virginia December 2015 By Roderick H. Simmons City of Alexandria Department of Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities, Natural Resources Division 2900-A Business Center Drive Alexandria, Virginia 22314 [email protected] Suggested citation: Simmons, R.H. 2015. Native vascular flora of the City of Alexandria, Virginia. City of Alexandria Department of Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities, Alexandria, Virginia. 104 pp. Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Climate ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Geology and Soils .................................................................................................................... 3 History of Botanical Studies in Alexandria .............................................................................. 5 Methods ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Results and Discussion .................................................................................................................... -

Northern Virginia

NORTHERN VIRGINIA SALAMANDER RESORT & SPA Middleburg WHAT’S NEW American soldiers in the U.S. Army helped create our nation and maintain its freedom, so it’s only fitting that a museum near the U.S. capital should showcase their history. The National Museum of the United States Army, the only museum to cover the entire history of the Army, opened on Veterans Day 2020. Exhibits include hundreds of artifacts, life-sized scenes re- creating historic battles, stories of individual soldiers, a 300-degree theater with sensory elements, and an experiential learning center. Learn and honor. ASK A LOCAL SPITE HOUSE Alexandria “Small downtown charm with all the activities of a larger city: Manassas DID YOU KNOW? is steeped in history and We’ve all wanted to do it – something spiteful that didn’t make sense but, adventure for travelers. DOWNTOWN by golly, it proved a point! In 1830, Alexandria row-house owner John MANASSAS With an active railway Hollensbury built a seven-foot-wide house in an alley next to his home just system, it’s easy for to spite the horse-drawn wagons and loiterers who kept invading the alley. visitors to enjoy the historic area while also One brick wall in the living room even has marks from wagon-wheel hubs. traveling to Washington, D.C., or Richmond The two-story Spite House is only 25 feet deep and 325 square feet, but on an Amtrak train or daily commuter rail.” NORTHERN — Debbie Haight, Historic Manassas, Inc. VIRGINIA delightfully spiteful! INSTAGRAM- HIDDEN GEM PET- WORTHY The menu at Sperryville FRIENDLY You’ll start snapping Trading Company With a name pictures the moment features favorite like Beer Hound you arrive at the breakfast and lunch Brewery, you know classic hunt-country comfort foods: sausage it must be dog exterior of the gravy and biscuits, steak friendly. -

Volume IV Falmouth Village

STAFFORD COUNT Y MASTER REDEVELOPMENT PLAN VOLUME IV: FALMOUTH VILLAGE OCTOBER 2009 | ADOPTED MAY 17, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS RESEARCH & PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT CULTURAL & HISTORIC RESOURCES ANALYSIS . .20 APPENDICES History of the Falmouth Village Redevelopment Area . 20 FALMOUTH VILLAGE CULTURAL & HERITAGE TOURISM AREA . .3 Architectural Design Guidelines . 21 APPENDIX I Archaeology . 21 Rugby, Tennessee: Heritage Tourism Case Study . 43 ECONOMIC & MARKET ANALYSIS OVERVIEW . 5 Belmont-Ferry Farm Trail . 21 Cultural & Heritage Tourism . 6 The Counting House . 21 APPENDIX II Heritage Tourist Characteristics . 6 Other Projects . 21 Additional Cultural & Historic Resources: History, Growth, & Historic Challenges of Heritage Tourism . 6 Preservation of the Redevelopment Area . 43 FALMOUTH VILLAGE REDEVELOPMENT AREA: Analysis of Falmouth Village as a Cultural Heritage Tourism Destination . 6 SUMMARY & CONCLUSIONS . 23 Strengths . 6 APPENDIX III Weaknesses . 6 Economic & Market Analysis . 23 Frequently Used Acronyms . 44 Opportunities . 7 Infrastructure & Storm Water Management (SWM) Analysis . 23 APPENDIX IV Threats . 7 Transportation & Traffic Analysis . 24 Research & Program Development Bibliography . 45 Falmouth Village Cultural, Heritage and Recreation Resource Concept . 7 Cultural & Historic Resources Analysis . 24 APPENDIX V REAL ESTATE MARKET & DEMAND . 8 MOVING FORWARD . 25 Public Workshop #1 Results . 46 Office Demand . 8 Retail Demand . 8 CONCEPT MASTER REDEVELOPMENT APPENDIX VI Public Workshop #2 Results . 57 INFRASTRUCTURE & STORM WATER MANAGEMENT (SWM) ANALYSIS . .9 PLAN & RECOMMENDATIONS Storm Water Management (SWM) Analysis . 9 APPENDIX VII PUBLIC PROCESS & COMMUNITY INPUT . .29 Existing Impervious Analysis . 10 Financial Feasibility: Assumptions & Methodology . 62 Regional SWM Opportunities . 11 Public Workshop # 1 Conclusions . 29 Water/Sewer Analysis . 12 Public Input: Dot Maps . 30 APPENDIX VIII Existing Water Service . 12 Visual Preference Survey . -

Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Working for You!

American Council of Engineering Companies of Metropolitan Washington Water & Wastewater Business Opportunities Networking Luncheon Presented by Matthew Doyle, Branch Chief, Wastewater Design and Construction Division Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Working for You! A Fairfax County, VA, publication August 20, 2019 Introduction • Matt Doyle, PE, CCM • Working as a Civil Engineer at Fairfax County, DPWES • BSCE West Virginia University • MSCE Johns Hopkins University • 25 years in the industry (Mid‐Atlantic Only) • Adjunct Hydraulics Professor at GMU • Director GMU‐EFID (Student Organization) Presentation Objectives • Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Infrastructure • Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Organization (Staff) • Snapshot of our Current Projects • New Opportunities To work with DPWES • Use of Technologies and Trends • Helpful Hyperlinks Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Infrastructure • Wastewater Collection System • 3,400 Miles of Sanitary Sewer (Average Age 60 years old) • 61 Pumping Stations (flow ranges are from 25 GPM to 25 MGD) • 90 Flow Meters (Mostly billing meters) • 135 Grinder pumps • Wastewater Treatment Plant • 1 Wastewater Treatment Plant • Noman M. Cole Pollution Control Plant, Lorton • 67 MGD • Laboratory • Reclaimed Water Reuse System • 6.6 MGD • 2 Pump Stations • 0.750 MG Storage Tank • Level 1 Compliance • Convanta, Golf Course and Ball Fields Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Organization • Wastewater Management Program (Three Areas) – Planning & Monitoring: • Financial, -

US Presidents

US Presidents Welcome, students! George Washington “The Father of the Country” 1st President of the US. April 30,1789- March 3, 1797 Born: February 22, 1732 Died: December 14, 1799 Father: Augustine Washington Mother: Mary Ball Washington Married: Martha Dandridge Custis Children: John Parke Custis (adopted) & Martha Custis (adopted) Occupation: Planter, Soldier George Washington Interesting Facts Washington was the first President to appear on a postage stamp. Washington was one of two Presidents that signed the U.S. Constitution. Washington's inauguration speech was 183 words long and took 90 seconds to read. This was because of his false teeth. Thomas Jefferson “The Man of the People” 3rd president of the US. March 4, 1801 to March 3, 1809 Born: April 13, 1743 Died: July 4, 1826 Married: Martha Wayles Skelton Children: Martha (1772-1836); Jane (1774-75); Mary (1778-1804); Lucy (1780-81); Lucy (1782-85) Education: Graduated from College of William and Mary Occupation: Lawyer, planter Thomas Jefferson Interesting Facts Jefferson was the first President to shake hands instead of bow to people. Thomas Jefferson was the first President to have a grandchild born in the White House. Jefferson's library of approximately 6,000 books became the basis of the Library of Congress. His books were purchased from him for $23,950. Jefferson was the first president to be inaugurated in Washington, D.C. Abraham Lincoln “Honest Abe” 16th President of the US. March 4, 1861 to April 15, 1865 Born: February 12, 1809 Died: April 15, 1865, Married: Mary Todd (1818-1882) Children: Robert Todd Lincoln (1843-1926); Edward Baker Lincoln (1846-50); William Wallace Lincoln (1850-62); Thomas "Tad" Lincoln (1853-71) Occupation: Lawyer Abraham Lincoln Interesting Facts Lincoln was seeing the play "Our American Cousin" when he was shot. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Board Agenda Item July 30, 2019 ACTION

Board Agenda Item July 30, 2019 ACTION - 8 Endorsement of Design Plans for the Richmond Highway Corridor Improvements Project from Jeff Todd Way to Sherwood Hall Lane (Lee and Mount Vernon Districts) ISSUE: Board endorsement of the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) Design Public Hearing plans for the 3.1-mile Richmond Highway Corridor Improvements Project between Jeff Todd Way/Mount Vernon Memorial Highway and Sherwood Hall Lane. The purpose of the project is to increase capacity, safety, and mobility for all users. Improvements include widening Richmond Highway from four to six lanes; reserving the median for the future Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system; replacing structures over Dogue Creek, Little Hunting Creek, and the North Fork of Dogue Creek; intersection improvements; sidewalks; and two-way cycle tracks on both sides of the road. RECOMMENDATION: The County Executive recommends that the Board endorse the design plans for the Richmond Highway Corridor Improvements project administered by VDOT as generally presented at the March 26, 2019, Design Public Hearing and authorize the Director of FCDOT to transmit the Board’s endorsement to VDOT (Attachment I). TIMING: The Board should take action on this matter on July 30, 2019, to allow VDOT to proceed with final design plans and enter the Right-of-Way (ROW) phase in late 2019 to keep the project on schedule. BACKGROUND: In 1994, the Virginia General Assembly directed VDOT to perform a centerline design study of the 27-mile Route 1 corridor between the Stafford County line and the Capital Beltway. There was a continuation of the Centerline Study in 1996 and 1998. -

2019 Trout Program Maps

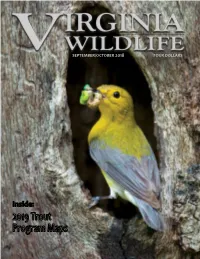

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 FOUR DOLLARS Inside: 2019 Trout Program Maps SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 Contents 5 How Sweet Sweet Sweet It Is! By Mike Roberts With support from the Ward Burton Wildlife Foundation, volunteers, and business partners, a citizen science project aims to help a magnificent songbird in the Roanoke River basin. 10 Hunting: A Foundation For Life By Curtis J. Badger A childhood spent afield gives the author reason to reflect upon a simpler time, one that deeply shaped his values. 14 Women Afield: Finally By John Shtogren There are many reasons to cheer the trend of women’s interest in hunting and fishing, and the outdoors industry takes note. 20 What’s Up With Cobia? By Ken Perrotte Virginia is taking a lead in sound management of this gamefish through multi-state coordination, tagging efforts, and citation data. 24 For The Love Of Snakes By David Hart Snakes are given a bad rap, but a little knowledge and the right support group can help you overcome your fears. 28 The Evolution Of Cute By Jason Davis Nature has endowed young wildlife with a number of strategies for survival, cuteness being one of them. 32 2019 Trout Program Maps By Jay Kapalczynski Fisheries biologists share the latest trout stocking locations. 38 AFIELD AND AFLOAT 41 A Walk in the Woods • 42 Off the Leash 43 Photo Tips • 45 On the Water • 46 Dining In Cover: A female prothonotary warbler brings caterpillars to her young. See page 5. ©Mike Roberts Left: A handsome white-tailed buck pauses while feeding along a fence line. -

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Fred A

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER TWENTY-SIX This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archcological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents. GEORGE WASHINGTON BIRTHPLACE National Monument Virginia by J. Paul Hudson NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 26 Washington, D. C, 1956 The National Park System, of which George Washington Birthplace National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. Qontents Page JOHN WASHINGTON 5 LAWRENCE WASHINGTON 6 AUGUSTINE WASHINGTON 10 Early Life 10 First Marriage 10 Purchase of Popes Creek Farm 12 Building the Birthplace Home 12 The Birthplace 12 Second Marriage 14 Virginia in 1732 14 GEORGE WASHINGTON 16 THE DISASTROUS FIRE 22 A CENTURY OF NEGLECT 23 THE SAVING OF WASHINGTON'S BIRTHPLACE 27 GUIDE TO THE AREA 33 HOW TO REACH THE MONUMENT 43 ABOUT YOUR VISIT 43 RELATED AREAS 44 ADMINISTRATION 44 SUGGESTED READINGS 44 George Washington, colonel of the Virginia militia at the age of 40. From a painting by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy, Washington and Lee University. IV GEORGE WASHINGTON "... His integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives . -

A Ceremonial Desk by Robert Walker, Virginia Cabinetmaker by Sumpter Priddy

A Ceremonial Desk by Robert Walker, Virginia Cabinetmaker by Sumpter Priddy Fig. 1: Desk, attributed to the shop of Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia ca. 1750. Walnut primary; yellow pine secondary. H. 44, W. 43˙, D. 23˙ in. The desk originally had a bookcase, which is now missing. 2009 Antiques & Fine Art 159 his commanding desk is among the most significant discoveries in Southern furniture to come to 1 T light in recent decades. The desk’s remarkable iconography — including hairy paw feet, knees carved with lions’ heads, and the bust of a Roman statesman raised in relief on its prospect door — is rare in colonial America (Figs. 1–1b). Two of these elements appear in tandem on only one other piece of colonial furniture, a ceremo- nial armchair used by Virginia’s Royal Governors at the Capitol in Williamsburg 2 (Fig. 2). Not surprisingly, an intriguing trail of evidence suggests that this desk was owned by Virginia’s Royal Governor Thomas Lee (ca. 1690–1750), the master of Stratford, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, and kinsman of Robert E. Lee, the celebrated general of the Confederate forces during the American Civil War. The desk is attributed with certainty to the Scottish émigré cabinetmaker Robert Walker (1710–1777) of King George County, Fig. 1b: Detail of one Virginia. Robert and his older brother, William of the legs of figure 1. (ca.1705–1750), a talented house joiner, found themselves in great demand among the wealth- iest families in the colony and often worked in tandem building and furnishing houses. Extensive research undertaken by Robert Leath, Director of Collections for the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, has uncovered strong documentary evidence related to the Walkers, their patrons, and their furniture, 3 and has effected a re-evaluation of baroque and rococo style in the early Chesapeake.