A Ceremonial Desk by Robert Walker, Virginia Cabinetmaker by Sumpter Priddy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Presidents

US Presidents Welcome, students! George Washington “The Father of the Country” 1st President of the US. April 30,1789- March 3, 1797 Born: February 22, 1732 Died: December 14, 1799 Father: Augustine Washington Mother: Mary Ball Washington Married: Martha Dandridge Custis Children: John Parke Custis (adopted) & Martha Custis (adopted) Occupation: Planter, Soldier George Washington Interesting Facts Washington was the first President to appear on a postage stamp. Washington was one of two Presidents that signed the U.S. Constitution. Washington's inauguration speech was 183 words long and took 90 seconds to read. This was because of his false teeth. Thomas Jefferson “The Man of the People” 3rd president of the US. March 4, 1801 to March 3, 1809 Born: April 13, 1743 Died: July 4, 1826 Married: Martha Wayles Skelton Children: Martha (1772-1836); Jane (1774-75); Mary (1778-1804); Lucy (1780-81); Lucy (1782-85) Education: Graduated from College of William and Mary Occupation: Lawyer, planter Thomas Jefferson Interesting Facts Jefferson was the first President to shake hands instead of bow to people. Thomas Jefferson was the first President to have a grandchild born in the White House. Jefferson's library of approximately 6,000 books became the basis of the Library of Congress. His books were purchased from him for $23,950. Jefferson was the first president to be inaugurated in Washington, D.C. Abraham Lincoln “Honest Abe” 16th President of the US. March 4, 1861 to April 15, 1865 Born: February 12, 1809 Died: April 15, 1865, Married: Mary Todd (1818-1882) Children: Robert Todd Lincoln (1843-1926); Edward Baker Lincoln (1846-50); William Wallace Lincoln (1850-62); Thomas "Tad" Lincoln (1853-71) Occupation: Lawyer Abraham Lincoln Interesting Facts Lincoln was seeing the play "Our American Cousin" when he was shot. -

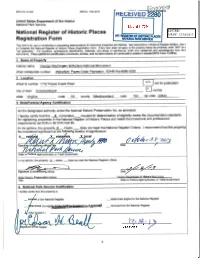

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NOV 0 ·~ 2013 National Register of Historic Places NAT. Re018TiR OF HISTORIC PlACES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name George Washington Birthplace National Monument other names/site number Wakefield. Popes Creek Plantation , VDHR File #096-0026 2. Location 1732 Popes Creek Road not for publication street & number L-----' city or town Colonial Beach ~ vicinity state Vir inia code VA county Westmoreland code _ _;_:19'--=-3- zip code -"'2=2:....;.4"""43.;;...._ ___ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _!__nomination_ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property .K._ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: x_ b state ' Ide "x n J.VIA.rVI In my opinion, the property .x..._ meets_ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Johannes Spitler, a Virginia Furniture Decorator at the Turn of the 19Th Century by Chris Shelton*

Johannes Spitler, a Virginia Furniture Decorator at the Turn of the 19th Century by Chris Shelton* Abstract: This paper highlights the usefulness of objective technical information obtained by conservators in expanding the understanding of American folk art objects, particularly painted furniture. This topic is presented through the research on the materials and methods used by Johannes Spitler, an German-American furniture decorator active in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. A tall case clock and a recently acquired blanket chest both painted by Spitler were examined and treated in the furniture conservation laboratory of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. These objects are presently on display in the new exhibition areas at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center in Williamsburg. Introduction: With the inception of American folk art as a collected art form in the 1920’s, collectors sought to acquire objects which satisfied the aesthetics of both the art connoisseur and the antiquarian. Painted objects in particular have been approached with a curious mix of fine arts aesthetics and a love of patina. Along with this folk art aesthetic collectors have been driven by many preconceived notions of the nature and importance of folk art. Chief among these is the romantic association of folk art with the new American democracy, that is, “the art of a sovereign, if uncultivated, folk living on an expanding frontier, cut off from the ancient traditions of race, religion and class.”1 These earlier values have shaped many major collections but are now being reevaluated by curators, folk lorists, and historians. In a 1986 conference on folk art, John Michael Vlach presented the situation found in many museum collections today: Generally folk art has been pursued as a set of things,.. -

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Fred A

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER TWENTY-SIX This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archcological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents. GEORGE WASHINGTON BIRTHPLACE National Monument Virginia by J. Paul Hudson NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 26 Washington, D. C, 1956 The National Park System, of which George Washington Birthplace National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. Qontents Page JOHN WASHINGTON 5 LAWRENCE WASHINGTON 6 AUGUSTINE WASHINGTON 10 Early Life 10 First Marriage 10 Purchase of Popes Creek Farm 12 Building the Birthplace Home 12 The Birthplace 12 Second Marriage 14 Virginia in 1732 14 GEORGE WASHINGTON 16 THE DISASTROUS FIRE 22 A CENTURY OF NEGLECT 23 THE SAVING OF WASHINGTON'S BIRTHPLACE 27 GUIDE TO THE AREA 33 HOW TO REACH THE MONUMENT 43 ABOUT YOUR VISIT 43 RELATED AREAS 44 ADMINISTRATION 44 SUGGESTED READINGS 44 George Washington, colonel of the Virginia militia at the age of 40. From a painting by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy, Washington and Lee University. IV GEORGE WASHINGTON "... His integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives . -

George Washington: a National Treasure

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, WASHINGTON, DC HIGH SCHOOL EDITION VOLUME 2, NO. 6, SPRING 2004 george washington the PATRIOT n.PatriotPapers [Fr patriote < LL. patriota, fellow countryman < Gr patriotes < patris, fatherland <pater, FATHER] a national treasure George Washington Visits George, Washington National Portrait Gallery Exhibition Tours, Opens in Little Rock, Arkansas The van itself wasn’t that unusual—a two-door, three- seat white Ford van. It was what was inside that caused Coming Soon to a Museum Near You all the commotion. Most people don’t expect George The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: Washington, in uniform, to come riding through town. February 15 - June 16, 2002 Nor would he stop for gas or eat at the local diner. But Las Vegas Art Museum: that’s what he did in the state of Washington, in the June 28 - October 27, 2002 month of March 2003, and the locals took note. Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Dubbed “The George Tour,” this journey across November 7, 2002 - March 9, 2003 Washington State was organized by the Seattle Art Seattle Art Museum: March 21 - July 20, 2003 Museum in conjunction with its visiting exhibition The Minneapolis Institute of Arts: “George Washington: A National Treasure.” The August 1 - November 30, 2003 National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Oklahoma City Museum of Art: has mounted this exhibition to tour the famous December 12, 2003 - April 11, 2004 Lansdowne portrait painted by Gilbert Stuart in Arkansas Arts Center: April 23 - August 22, 2004 1796. The painting has already visited six of eight The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Fall 2004 venues across the country; the tour is made possible through the generosity of the Donald W. -

Uncovering the Identity of a Northern Shenandoah Valley Cabinetmaking Shop

A Southern Backcountry Mystery: Uncovering the Identity of a Northern Shenandoah Valley Cabinetmaking Shop by Patricia Long-Jarvis B.A. in Art History, December 1980, Scripps College A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts January 8, 2021 Thesis directed by Oscar P. Fitzgerald Adjunct Professional Lecturer of Decorative Arts & Design History i © Copyright 2020 by Patricia Long-Jarvis All rights reserved ii Dedication I wish to dedicate this thesis to my husband, Jim, our four children—James, Will, Garen, and Kendall—and my sister, Jennifer, for their unfailing support and belief in me. I am eternally grateful to Jim for his patience and providing the time and space away from our family while I researched the Newbrough & Hendricks story. Jim’s absolute love and unwavering confidence are why I completed this study. iii Acknowledgments The author wishes to thank the following individuals and institutions for their support and assistance in making this thesis a reality. My professor, mentor, and thesis advisor, Dr. Oscar P. Fitzgerald, who inspired my love for American furniture, and insisted from the beginning that I write a thesis versus taking a comprehensive exam. For the past three years, Oscar has patiently awaited the delivery of my thesis, and never lost his enthusiasm for the study. I will always be profoundly grateful for his wisdom, guidance, and confidence in me, and all I have learned from him as a teacher, scholar, and thesis advisor. -

Robert Beverley and the Furniture Ofblandfield, Essex County, Virginia, 1760-1800

Robert Beverley and the Furniture ofBlandfield, Essex County, Virginia, 1760-1800 Christopher Harvey Jones Submitted in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree Master ofArts in the History ofDecorative Arts Masters Program in the History ofDecorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates And Corcoran College ofArt + Design 2006 ©2006 Christopher Harvey Jones All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations 11 Acknowledgments IV Introduction 1 Chapter One - Robert Beverley -- Colonial Gentleman 5 Chapter Two - Choices and Constraints 19 Chapter Three - Blanc!field 28 Chapter Four - Conspicuous Consumption -- English Furniture at Blanetfield 42 . Chapter Five - American Pragmatist -- Virginia Furniture at Blanetfield 53 Conclusion - Robert Beverley -- American 69 Bibliography 72 Appendix One 77 Illustrations 80 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations II Acknowledgments IV Introduction 1 Chapter One - Robert Beverley -- Colonial Gentleman 5 Chapter Two - Choices and Constraints 19 Chapter Three - Blanctfield 28 Chapter Four - Conspicuous Consumption -- English Furniture at Blan4field 42 . Chapter Five - American Pragmatist -- Virginia Furniture at Blan4field 53 Conclusion - Robert Beverley -- American 69 Bibliography 72 Appendix One 77 Illustrations 80 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure One -- Essex County, Virginia, 1755, A New Map ofthe Most Inhabited Part of Virginia ...by Thomas Frye and Peter Jefferson, Detail, Library of Congress. Figure Two -- Blandfield, East (River) Front, Historic American Buildings Survey Photograph, Ca. 1983, Library of Congress. Figure Three -- Blandfie1d, West (Entry) Front, Historic American Buildings Survey Photograph, ca.1983, Library of Congress. Figure Four -- Conjectural Floor Plan, Blandfie1d, Essex County, Virginia. Figure Five -- Side Chair, Solid Splat, Mahogany (?) England, Ca. 1750 - 1775, Private Collection, Author Photograph. Figure Six -- Side Chair, Diamond Splat, Walnut, England, Ca. -

GEORGE WASHINGTON George Washington Was Born at His Father's

GEORGE WASHINGTON George Washington was born at his father's plantation on Pope's Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on February 22, 1732. His father, Augustine Washington, was a leading planter in the area and also served as a justice of the county court. Augustine's first wife, Janet Butler, died in 1729, leaving him with two sons, Lawrence and Augustine, Jr., and a daughter, Jane. The elder Augustine then married George's mother, Mary Ball, in 1731. George was the eldest of Augustine Washington's and Mary Ball's six children. In 1735, when George was three, Augustine moved the family up the Potomac River to another Washington home, Little Hunting Creek Plantation (later renamed Mount Vernon). In Stafford County, Augustine owned 1,600 acres on which there was a rich deposit of high-quality iron ore. The British-owned Principio Company extracted the ore from the Washington property and smelt it in a cold-blast charcoal furnace. (located behind today’s Colonial Forge High School). Iron ingots were shipped to England, with Augustine receiving money upon their delivery overseas. The furnace was a thriving enterprise from 1726 until 1735 when John England, the manager of the property, died. Problems arose from inadequate management. So in 1738, Augustine, wanting to be closer to the forge, moved his family to a farm on the Rappahannock River, now called Ferry Farm. George lived there from the time his was six until he was twenty years old. It was here that he learned the values and developed the character that would influence the rest of his life. -

Washington and Yorba

GENEALOGY OF THE WASHINGTON AND YORBA AND RELATED FAMILIES OUN1Y C/'.\Llf ORNIP ORA~\G~ . COG .' \CJ.\L SOC\E1)' GtNtJ\L Washington and Related Families - Washington Family Chart I M- Amphillus Twigden 6 Lawrence Washington 001-5. Thomas Washington, b. c. 1605, Margaret (Butler) Washington d. in Spain while a page to Prince Charles (later King Charles II) 1623. 001-1. Robert Washington, b. c. 1589, Unmd. eldest son and heir, d.s.p. 1610 Chart II 001-2. Sir John Washington of Thrapston, d. May 18, 1688. 1 Lawrence Washington M- 1st - Mary Curtis, d. Jan. 1, 1624 or Amphillus (Twigden) Washington 2 25, and bur. at Islip Ch. • M- 2nd - Dorothy Pargiter, d. Oct. 15, 002-1. John Washington, b. in Eng. 1678. 3 1632 or 1633, and emg. to VA c. 1659. He was b. at Warton Co. Lancaster, Eng. 001-3. Sir William Washington of He settled at Bridge's Creek, VA, and d. Packington, b. c. 1594, bur. Jun. 22, Jan. 1677. 1643, St. Martin's m the Field, M- 1st - Anne Pope, dtr of Nathaniel Middlesex Pope of Pope's Creek, VA. M- Anne Villiers 4 M- 2nd - Anne Brett M- 3rd - Ann Gerrard M- 4th - Frances Gerrard Speke Peyton 001-4. Lawrence Washington 5 Appleton 7 1 He was knighted at Newmarkel, Feb. 2 1, 1622 or 23. He 002-2. Lawrence Washington, bap. at and other members of his family often visited Althorpe, the Tring, Co. Hertfordshire, Jun. 18, 1635, home of the Spencers. He is buried in the Parish Ch. -

College of Arts and Letters Maj

COLLEGE OF ARTS AND LETTERS MAJ. YEAR TITLE BUSINESS CITY STATE Art 2007 Clerk USCG Alexandria VA Communication 2014 Film Specialist University of Texas at Austin Austin TX Communication 2014 Graduate Student Syracuse University Winchester VA Communication 2014 Marketing Coordinater Monarch Mortgage Virginia Beach VA Communication 2014 Production Instructor School of Creative and Performing Arts Lorton VA Communication 2013 Graphics & Promotions Coordinator Ocean Breeze Waterpark Virginia Beach VA Communication 2013 Sales Associate Tumi Washington DC Communication 2013 Recriter Aerotek Norfolk VA Communication 2013 Operations Administration The Franklin Johnston Group Chesapeake VA Communication 2013 Social Media Specialist Dominion Enterprises Newport News VA Communication 2013 Realtor Rose & Womble Realty Chesapeake VA Communication 2013 Legal Assistant Harry R. Purkey, Jr. P.C. Virginia Beach VA Communication 2012 Public Relations Asst Account Executive BCF Virginia Beach VA Communication 2012 Event Designer Amphora Catering Annandale VA Communication 2012 Assistant Manager Mark's Bar-B-Que Zone LLC Marion VA Communication 2012 Assignment Editor WTVR-TV Richmond VA Communication 2012 Team Leader Neebo Bookstores at John Tyler Community College Virginia Beach VA Communication 2012 Marketing and Communiactions Coordinator The Pacific Club Wahiawa HI Communication 2012 Leadership Consultant Omicron Delta Kappa Lexington VA Communication 2011 Regional Vice President Specialists On Call, Inc. Ocean City MD Communication 2011 Administrative Assistant Eagle Haven Golf Course Virginia Beach VA Communication 2011 Account Manager Bizport Laguna Niguel CA Communication 2011 Human Resources Officer U.S. Army Apo AP Communication 2011 REALTOR Long & Foster Real Estate Inc. Franklin VA Communication 2011 Marketing Communications Specialist Crawford Group Campbell CA Communication 2011 Social Media Specialist Meridian Group Virginia Beach VA Communication 2011 Assoc. -

4~~~I

VIRGINIA HISTORIC SITES: ARE THEY ACCESSIBLE TO THE MOBILITY IMPAIRED? by Andrea Edwards Gray Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Housing, Interior Design and Resource Management APPROVED: /' !ZULU;' ~ 4~~~i:::-- tmM:f< R emary C. Goss Nancy K. Canestaro Novembe~, 1988 Blacksburg, Virginia f"i I LD S~s~ V8ss-' \gSS &11-1& c.;L VIRGINIA HISTORIC SITES: ARE THEY ACCESSIBLE TO THE MOBILITY IMPAIRED? by Andrea Edwards Gray Dr. Jeanette E. Bowker, Chairman Housing, Interior Design and Resource Management (ABSTRACT) The purpose of the study was to determine how historic organizations in Virginia have responded to the issue of handicapped ) accessibility at their properties. The study sought to determine which historic sites are accessible to the mobility impaired, what handicapped accessible features exist in the sites' buildings and what adaptations have been made to programs and activities taking place at the sites. The study also involved exploring reasons why some historic organizations have not made their buildings and programs accessible to the disabled and determining what future plans the historic organizations have for making their sites accessible to all people. Questionnaires were sent to 228 historic sites in Virginia; 147 of the returned surveys met the research criteria. Even though most sites had at least one handicapped accessible feature, only 40 sites were reported to be accessible to everyone. Video-tours, slides and large photographs are made available to visitors who cannot participate in the entire tour at some of the historic sites. -

Advancing the World's Best Little Town

Advancing the World’s Best Little Town Town of Bedford Comprehensive Plan Adopted June 13, 2017 TOWN COUNCIL Robert T. Wandrei, Mayor Timothy W. Black, Vice Mayor Stacey L. Hailey Bruce M. Johannessen Steve C. Rush F. Bryan Schley James A. Vest PLANNING COMMISSION Lonne R. Bailey, Chair Darren Shoen, Vice Chair Larry Brookshier Frances B. Coles Jason L. Horne Jim Towner Steve C. Rush, Town Council Representative TOWN STAFF AND OFFICIALS Barrett F. Warner, Interim Town Manager Sonia M. Jammes, Finance Director John B. Wagner, Electric Director D.W. Lawhorne, Jr., Director of Public Works F. Todd Foreman, Chief of Police Brad Creasy, Fire Chief William W. Berry, IV, Town Attorney I. INTRODUCTION AND HISTORICAL SUMMARY A. PURPOSE OF COMPREHENSIVE PLAN The Comprehensive Plan is a means for local government officials and citizens to express their goals for the future of their community. The Virginia General Assembly requires that local governments adopt a comprehensive plan and review it every 5 years in order to best promote the health, safety, morals, order, convenience, prosperity and general welfare of the inhabitants. The Comprehensive Plan examines past trends and existing conditions in order to gain insight into future trends. Citizens, through the Planning Commission and Town Council, set goals, objectives and policies to guide governmental decisions and overall development. The comprehensive plan is general in nature, but does establish implementation strategies that can acutely affect the character of the community. The comprehensive plan guides the establishment and construction of public areas or structures or other facilities as carried out by the planning commission.