The Emergence of a Nonviolent Society in Czechoslovakia 1989

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements

BETWEEN MAO AND GANDHI: STRATEGIES OF VIOLENCE AND NONVIOLENCE IN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by CHES THURBER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard Shultz, Chair H. Zeynep Bulutgil Erica Chenoweth CHES THURBER 104 E. Main St. #2, Gloucester, MA 02155 [email protected] | (617) 710-2617 DOB: September 21, 1982 in New York, NY, USA EDUCATION Tufts University, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy PH.D. | International Relations (2015) Dissertation: “Between Mao and Gandhi: Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements” Committee: Richard Shultz, Zeynep Bulutgil, Erica Chenoweth M.A.L.D. | International Relations (2010) Middlebury College B.A. | International Studies (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 2004) ACADEMIC University of Chicago APPOINTMENTS Postdoctoral Fellow, Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (Beginning Aug. 1, 2015) Program on Political Violence Harvard University Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2014-2015) International Security Program PUBLICATIONS “Militias as Sociopolitical Movements: Lessons from Iraq’s Armed Shia Groups" in Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, nos. 5-6 (October 2014): 900-923. Review of The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Mahendra Lawoti and Anuk K. Pahari, in Himalaya 34, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 148-150. “A Step Short of the Bomb: Explaining the Strategy of Nuclear Hedging” in Journal of Public and International Affairs (2011). “From Coexistence to Cleansing: The Rise of Sectarian Violence in Baghdad, 2003-2006” in al-Nakhlah: Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization (March 2011). -

Civil Resistance Against Coups a Comparative and Historical Perspective Dr

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Civil Resistance Against Coups A Comparative and Historical Perspective Dr. Stephen Zunes ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover Photos: (l) Flickr user Yamil Gonzales (CC BY-SA 2.0) June 2009, Tegucigalpa, Honduras. People protesting in front of the Presidential SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski Palace during the 2009 coup. (r) Wikimedia Commons. August 1991, CONTACT: [email protected] Moscow, former Soviet Union. Demonstrators gather at White House during the 1991 coup. VOLUME EDITOR: Amber French DESIGNED BY: David Reinbold CONTACT: [email protected] Peer Review: This ICNC monograph underwent four blind peer reviews, three of which recommended it for publication. After Other volumes in this series: satisfactory revisions ICNC released it for publication. Scholarly experts in the field of civil resistance and related disciplines, as well as People Power Movements and International Human practitioners of nonviolent action, serve as independent reviewers Rights, by Elizabeth A. Wilson (2017) of ICNC monograph manuscripts. Making of Breaking Nonviolent Discipline in Civil Resistance Movements, by Jonathan Pinckney (2016) The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle, by Tenzin Dorjee (2015) Publication Disclaimer: The designations used and material The Power of Staying Put, by Juan Masullo (2015) presentedin this publication do not indicate the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ICNC. The author holds responsibility for the selection and presentation of facts contained in Published by ICNC Press this work, as well as for any and all opinions expressed therein, which International Center on Nonviolent Conflict are not necessarily those of ICNC and do not commit the organization 1775 Pennsylvania Ave. NW. Ste. -

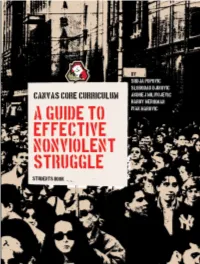

Canvas Core Curriculum: a Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle

CANVAS CORE CURRICULUM: A GUIDE TO EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE STUDENTS BOOK by CANVAS printed and published in Serbia 2007 CANVAS Curriculum Introduction Before you is a wealth of knowledge about the planning, conduct, and Srdja Popovic, Slobodan Djinovic, Andrej Milivojevic, Hardy Merriman evaluation of strategic nonviolent conflict. This curriculum guide will be a and Ivan Marovic valuable companion to new and experienced activists, as well as to others who wish to learn about this subject. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle Copyright 2007 by CANVAS. All rights reserved. The authors combine classic insights about nonviolent conflict with new ideas based on recent experience. The result is a synthesis that pushes the Published in Serbia, 2007. limits of what we thought nonviolent strategies were capable of achieving. The material covered includes time-tested analyses of power, different ISBN 978-86-7596-087-4 methods of nonviolent action, and ways to create a strategic plan for developing and mobilizing a movement. In addition, the authors include new material about how to: Publisher: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) • chart a movement’s history and progress (Chapter 8) Masarikova 5/ XIII, Belgrade, Serbia, www.canvasopedia.org • use marketing, branding, and effective communication techniques in a movement (Chapters 9 and 10) Graphic design and illustrations: Ana Djordjevic • address the effects of fear on a movement’s members (Chapter 13) • develop security measures within a movement (Chapter 14) Photo on cover: Igor Jeremic • manage a movement’s material resources, human resources, and time (Advanced Chapters 2-4) Throughout these topics, the authors emphasize pragmatic learning and draw on their own experience applying these ideas in their own struggles. -

The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: a Strategic and Historical Analysis

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: A Strategic and Historical Analysis Tenzin Dorjee ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover photos: (l) John Ackerly, 1987, (r) Invisible Tibet Blog SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski John Ackerly’s photo of the first major demonstration in Lhasa in 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] became an emblem for the Tibet movement. The monk Jampa Tenzin, who is being lifted by fellow protesters, had just rushed into a burning VOLUME EDITORS: Hardy Merriman, Amber French, police station to rescue Tibetan detainees. With his arms charred by the Cassandra Balfour flames, he falls in and out of consciousness even as he leads the crowd CONTACT: [email protected] in chanting pro-independence slogans. The photographer John Ackerly Other volumes in this series: became a Tibet advocate and eventually President of the International Campaign for Tibet (1999 to 2009). To read more about John Ackerly’s The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance experience in Tibet, see his book co-authored by Blake Kerr, Sky Burial: against Armed Groups in Colombia, Juan Masullo An Eyewitness Account of China’s Brutal Crackdown in Tibet. (2015) Invisible Tibet Blog’s photo was taken during the 2008 Tibetan uprising, The Maldives Democracy Experience (2008-13): when Tibetans across the three historical provinces of Tibet rose up From Authoritarianism to Democracy and Back, to protest Chinese rule. The protests began on March 10, 2008, a few Velezinee Aishath (2015) months ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games, and quickly became the largest, most sustained nonviolent movement Tibet has witnessed. Published by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict The designations used and material presented in this publication do P.O. -

YUGOSLAV REFUGEES, DISPLACED PERSONS and the CIVIL WAR Mirjana Morokvasic Freie Universitm, Berlin and Centre Nationale De La Recherche Scientifique, Paris

YUGOSLAV REFUGEES, DISPLACED PERSONS AND THE CIVIL WAR Mirjana Morokvasic Freie UniversitM, Berlin and Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris Background case among the socialist countries. The within the boundaries of former Slovenia and Croatia declared present tragedy can only be compared Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav case may also independence on 25 June 1991. That to that of the Second World War; from help de-dramatize the East I West was the date of the "collective an international perspective, the invasion scenarios which predict thanatos"' which led to the United Nations High Commission on disruptive mass movements caused by disintegration of Yugoslavia. As a Refugees (UNHCR) compares it in political and ethnic violence or result of German pressure, the scope, scale of atrocities and ecological catastrophe in the countries European Community, followed by a consequences for the population, to the aligned with the former Soviet empire. number of other states, recognized the Cambodian civil war. The Demographic Structure In three ways, analyzing the independence of the secessionist The 600,000 to 1 million displaced refugees' situation contributes to our republics on 15 January 1992 and persons referred to above come from understanding of issues beyond the buried the second Y~goslavia.~ Croatia, whose total population is 4.7 human tragedy of the people Although the Westernmedia have million (see Figure 1).Moreover, most themselves. First, it demystifies the now shifted their attention to the of these people come from a relatively genesis of the Yugoslav conflict, which former Soviet Union, where other small area the front line, which is now is often reduced to a matter "ethnic - similar and potentially even more under the control of the Yugoslav hatred." It shows that the separation of dangerous ethnic conflicts are brewing, Army and Serbian forces. -

Centralization in Nonviolent Civil Resistance Movements

United We Stand, Divided We Fall: Centralization in Nonviolent Civil Resistance Movements. By Evgeniia Iakhnis Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Erin K. Jenne CEU eTD Collection Word Count: 14,555 Budapest, Hungary 2012 Abstract This thesis examines how the level of centralization affects the outcome of nonviolent civil resistance campaigns. The findings of the statistical analysis show that campaigns led by a coalition or an umbrella organization are more likely to succeed than movements with other organizational structures, while spontaneous movements have lower chances to achieve political transformation. A detailed analysis of two cases of nonviolent resistance, Romania from 1987-1989 and Bulgaria in 1989, explores the casual mechanisms that link different levels of centralization to the outcome of nonviolent campaigns. It reveals that the existence of a strong coalition at the head of a nonviolent campaign enables the movement to conduct effective negotiations, prevents disruption of nonviolent discipline, and presents a viable political alternative once the previous regime falls. In contrast, the spontaneous character of a movement undermines its ability to conduct effective negotiations, maintain nonviolent discipline, and create a viable alternative on the political arena. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Erin Jenne for her support and invaluable advice. I also want to say a special thank you to Matthew Stenberg for his constructive criticism and patience while reading my thesis drafts. Without him, my experience at the CEU would have been different. -

Mary Elizabeth King on Civil Action for Social Change, the Transnational Women’S Movement, and the Arab Awakening

Theory Talks Presents THEORY TALK #55 MARY ELIZABETH KING ON CIVIL ACTION FOR SOCIAL CHANGE, THE TRANSNATIONAL WOMEN’S MOVEMENT, AND THE ARAB AWAKENING Theory Talks is an interactive forum for discussion of debates in International Relations with an emphasis of the underlying theoretical issues. By frequently inviting cutting-edge specialists in the field to elucidate their work and to explain current developments both in IR theory and real-world politics, Theory Talks aims to offer both scholars and students a comprehensive view of the field and its most important protagonists. Citation: Kovoets, N. (2013) ‘Theory Talk #55: Mary Elizabeth King on Civil Action for Social Change, the Transnational Women’s Movement, and the Arab Awakening’, Theory Talks, http://www.theory-talks.org/2013/06/theory-talk-55.html (05-06-2013) WWW.THEORY-TALKS.ORG MARY ELIZABETH KING ON CIVIL ACTION FOR SOCIAL CHANGE, THE TRANSNATIONAL WOMEN’S MOVEMENT, AND THE ARAB AWAKENING Nonviolent resistance remains by and large a marginal topic to IR. Yet it constitutes an influential idea among idealist social movements and non-Western populations alike, one that has moved to the center stage in recent events in the Middle East. In this Talk, Mary King—who has spent over 40 years promoting nonviolence—elaborates on, amongst others, the women’s movement, nonviolence, and civil action more broadly. What is, according to you, the central challenge or principal debate in International Relations? And what is your position regarding this challenge/in this debate? The field of International Relations is different from Peace and Conflict Studies; it has essentially to do with relationships between states and developed after World War I. -

Authoritarian Politics and the Outcome of Nonviolent Uprisings

Authoritarian Politics and the Outcome of Nonviolent Uprisings Jonathan Sutton Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies/Te Ao o Rongomaraeroa University of Otago/Te Whare Wānanga o Otāgo July 2018 Abstract This thesis examines how the internal dynamics of authoritarian regimes influence the outcome of mass nonviolent uprisings. Although research on civil resistance has identified several factors explaining why campaigns succeed or fail in overthrowing autocratic rulers, to date these accounts have largely neglected the characteristics of the regimes themselves, thus limiting our ability to understand why some break down while others remain cohesive in the face of nonviolent protests. This thesis sets out to address this gap by exploring how power struggles between autocrats and their elite allies influence regime cohesion in the face of civil resistance. I argue that the degeneration of power-sharing at the elite level into personal autocracy, where the autocrat has consolidated individual control over the regime, increases the likelihood that the regime will break down in response to civil resistance, as dissatisfied members of the ruling elite become willing to support an alternative to the status quo. In contrast, under conditions of power-sharing, elites are better able to guarantee their interests, thus giving them a greater stake in regime survival and increasing regime cohesion in response to civil resistance. Due to the methodological challenges involved in studying authoritarian regimes, this thesis uses a mixed methods approach, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative data and methods to maximise the breadth of evidence that can be used, balance the weaknesses of using either approach in isolation, and gain a more complete understanding of the connection between authoritarian politics and nonviolent uprisings. -

Open Eppinger Final Thesis Submission.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THE WRITER’S ROLE IN NONVIOLENT RESISTANCE: VÁCLAV HAVEL AND THE POWER OF LIVING IN TRUTH MARGARET GRACE EPPINGER SPRING 2019 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in History and English with honors in History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Catherine Wanner Professor of History, Anthropology, and Religious Studies Thesis Supervisor Cathleen Cahill Associate Professor of History Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT In 1989, Eastern Europe experienced a series of revolutions that toppled communist governments that had exercised control over citizens’ lives for decades. One of the most notable revolutions of this year was the Velvet Revolution, which took place in Czechoslovakia. Key to the revolution’s success was Václav Havel, a former playwright who emerged as a political leader as a result of his writing. Havel went on to become the first president following the regime’s collapse, and is still one of the most influential people in the country’s history to date. Following the transition of Havel from playwright to political dissident and leader, this thesis analyzes the role of writers in nonviolent revolutions. Havel’s ability to effectively articulate his ideas gave him moral authority in a region where censorship was the norm and ultimately elevated him to a position of leadership. His role in Czechoslovak resistance has larger implications for writers and the significance of their part in revolutionary contexts. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... iii Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1 What is Resistance? ................................................................................... -

Strategic Nonviolent Power: the Science of Satyagraha Mark A

STRATEGIC NONVIOLENT POWER Global Peace Studies SERIES EDITOR: George Melnyk Global Peace Studies is an interdisciplinary series devoted to works dealing with the discourses of war and peace, conflict and post-conflict studies, human rights and inter- national development, human security, and peace building. Global in its perspective, the series welcomes submissions of monographs and collections from both scholars and activists. Of particular interest are works on militarism, structural violence, and postwar reconstruction and reconciliation in divided societies. The series encourages contributions from a wide variety of disciplines and professions including health, law, social work, and education, as well as the social sciences and humanities. SERIES TITLES: The ABCs of Human Survival: A Paradigm for Global Citizenship Arthur Clark Bomb Canada and Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Chantal Allan Strategic Nonviolent Power: The Science of Satyagraha Mark A. Mattaini STRATEGIC THE SCIENCE OF NONVIOLENT SATYAGRAHA POWER MARK A. MATTAINI Copyright © 2013 Mark A. Mattaini Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, AB T5J 3S8 ISBN 978-1-927356-41-8 (print) 978-1-927356-42-5 (PDF) 978-1-927356-43-2 (epub) A volume in Global Peace Studies ISSN 1921-4022 (print) 1921-4030 (digital) Cover and interior design by Marvin Harder, marvinharder.com. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Book Printers. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Mattaini, Mark A. Strategic nonviolent power : the science of satyagraha / Mark A. Mattaini. (Global peace studies, ISSN 1921-4022) Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued also in electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-927356-41-8 1. -

Civil Resistance in Ethiopia: an Overview of a Historical Development

Vol. 13(1), pp. 7-18, January-June 2021 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC2020.0471 Article Number: 216870165987 ISSN 2141-6672 Copyright ©2021 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article African Journal of History and Culture http://www.academicjournals.org/AJHC Review Civil resistance in Ethiopia: An overview of a historical development Amare Kenaw Aweke Department of Peace and Security Studies, School of Social Sciences and Humanities, Dire Dawa University (DDU) Ethiopia. Received 8 May, 2020; Accepted 26 May, 2020 A history of anti-government opposition in Ethiopia is a very complex topic and a subject extremely difficult to investigate. It runs through the analysis of intractable social crisis of the entire feudal empire covering a wide range of historical processes across ages to the various people’s movements in contemporary Ethiopia. It also involved different styles and methods over the years ranging from violent to nonviolent, and from dialogues and negotiations to conventional politics. The major purpose of this article is to provide a brief historical overview of the genesis, development, nature and dynamics of civil resistance in light of experiences ranging from the second half of 20th century to the 2015 Oromo and Amhara protest. Key words: Civil resistance, Ethiopian students movement, Ethiopian May-2005 election dissent, everyday forms of resistance, rebellions. INTRODUCTION A meticulous review of a history of anti-government some public writers2. opposition in Ethiopia gives an expanded list of both The materials produced at this time are important in violent and nonviolent resistance. It is also a very providing vivid insights on the genesis, foundation, and complex topic and has to explore the very complex crises radicalization of the late 1960s and early 1970s people‟s of the feudal empire, the Military regime and the movements in Ethiopia. -

Latin America's Authoritarian Drift

July 2013, Volume 24, Number 3 $12.00 Latin America’s Authoritarian Drift Kurt Weyland Carlos de la Torre Miriam Kornblith Putin versus Civil Society Leon Aron Miriam Lanskoy & Elspeth Suthers Kenya’s 2013 Elections Joel D. Barkan James D. Long, Karuti Kanyinga, Karen E. Ferree, and Clark Gibson The Durability of Revolutionary Regimes Steven Levitsky & Lucan Way Kishore Mahbubani’s World Donald K. Emmerson The Legacy of Arab Autocracy Daniel Brumberg Frédéric Volpi Frederic Wehrey Sean L. Yom Putin versus Civil Society The Long STruggLe for freedom Leon Aron Leon Aron is resident scholar and director of Russian studies at the American Enterprise Insitute, a Washington, D.C.–based think tank. His most recent book is Roads to the Temple: Memory, Truth, Ideals and Ideas in the Making of the Russian Revolution, 1987–1991 (2012). Civil unrest, no matter where it takes place, is always difficult to as- sess. For experts and policy makers, the dilemma is depicted by meta- phors as well-worn as they are accurate: Flash in the pan or tip of the iceberg? Do demonstrations and rallies manifest intense but fleeting anger and frustration? Or do they represent enduring sentiments that eventually may force major reforms or even a change in regime? Evaluating the prospects for Russia’s “new” protesters, who began to mobilize en masse after fraudulent State Duma elections in Decem- ber 2011, and the civil society from which they sprang is no exception. Perhaps history can help us to understand contemporary developments. Of course, no historical parallel is perfect, but though history is hardly an infallible guide, it is the only one we have and may have something to teach us here.