A Guide to the ALM Thesis Seventh Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Content Strategist

Phone: (203) 984-9170 Email: [email protected] LUCY THOMAS LinkedIn: http://linkedin.com/in/lucyethomas Digital Content Strategist Portfolio site: http://lucyethomas.com Results-oriented content strategist with experience leading teams to successfully execute complex digital projects and campaigns. Excellent communicator and relationship builder. ● Consistently increase user engagement across digital channels ● Proactively optimize processes and workflows ● Experience in highly regulated industries, including healthcare and finance SKILLS EXPERIENCE Documentation and content Ettain Group, Charlotte, NC — Content Strategist at Wells Fargo management tools: Jira, Confluence, MS Oce, JULY 2019 - PRESENT SharePoint, WordPress ● As part of the Wells Fargo Experience Design (XD) Design Systems team: Software: Sketch (basic), ○ Developed simplified documentation; trained new XD InVision, Adobe InDesign, team members on documentation, brand standards, and HubSpot, Constant Contact, guidelines. Campaign Monitor ○ Conducted user research, UX audits and developed Other: Google Analytics, information architecture maps. Google AdWords Red Ventures, Charlotte, NC — Lead Senior Content Strategist AWARDS JUNE 2018 - JUNE 2019 ● Led team of content strategists in partnership with a Fortune 500 Best Website - pharmaceutical company. School/University ● Managed continuous development and optimization of content Best Mobile Site - strategy; integrated content, creative and marketing strategies. School/University ● Supported content execution; developed and implemented The Webby Awards, 2017 content standardization and best practices. Gold Award: General Website Wyss Institute at Harvard University, Boston, MA — Digital - Biotechnology Content Strategist W3 Awards, 2017 JUNE 2015 - JUNE 2018 ● Managed the production and distribution of content via e-mail and across social media platforms, including digital media campaigns. ● Managed redesign of the Wyss Institute website, which received two Webby Awards and a W3 award in 2017. -

Report of the Task Force on University Libraries

Report of the Task Force on University Libraries Harvard University November 2009 REPORT OF THE TASK FORCE ON UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES November 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Strengthening Harvard University’s Libraries: The Need for Reform …………... 3 II. Core Recommendations of the Task Force …………………………………………. 6 III. Guiding Principles and Recommendations from the Working Groups …………... 9 COLLECTIONS WORKING GROUP …………………………………………. 10 TECHNOLOGICAL FUTURES WORKING GROUP …………………………… 17 RESEARCH AND SERVICE WORKING GROUP ……………………………… 22 LIBRARY AS PLACE WORKING GROUP ……………………………………. 25 IV. Conclusions and Next Steps ………………………………………………………….. 31 V. Appendices ……………………………………………………………………………. 33 APPENDIX A: TASK FORCE CHARGE ……………………………………… 33 APPENDIX B: TASK FORCE MEMBERSHIP ………………………………… 34 APPENDIX C: TASK FORCE APPROACH AND ACTIVITIES …………………. 35 APPENDIX D: LIST OF HARVARD’S LIBRARIES …………………………… 37 APPENDIX E: ORGANIZATION OF HARVARD’S LIBRARIES ………………... 40 APPENDIX F: CURRENT LANDSCAPE OF HARVARD’S LIBRARIES ………... 42 APPENDIX G: HARVARD LIBRARY STATISTICS …………………………… 48 APPENDIX H: TASK FORCE INFORMATION REQUEST ……………………... 52 APPENDIX I: MAP OF HARVARD’S LIBRARIES ……………………………. 55 2 STRENGTHENING HARVARD UNIVERSITY’S LIBRARIES: THE NEED FOR REFORM Just as its largest building, Widener Library, stands at the center of the campus, so are Harvard’s libraries central to the teaching and research performed throughout the University. Harvard owes its very name to the library that was left in 1638 by John Harvard to the newly created College. For 370 years, the College and the University that grew around it have had libraries at their heart. While the University sprouted new buildings, departments, and schools, the library grew into a collection of collections, adding new services and locations until its tendrils stretched as far from Cambridge as Washington, DC and Florence, Italy. -

Harvard University Fact Book 2004-2005

Harvard University Fact Book 2004 - 2005 T able of Contents ORGANIZATION Pages Central Administration 2 Faculties and Allied Institutions 3 Research and Academic Centers 4 – 5 PEOPLE Pages Degree Student Enrollment 6 – 9 Degrees Conferred 10 – 13 International Students 14 – 15 Non-Degree Students and Fellowship Programs 16 – 17 Faculty Counts 18 – 19 Staff Counts 20 – 21 RESOURCES Pages Tuition, Fees, and Financial Aid 22 – 25 Sponsored Research 26 – 30 Library 31 – 32 FY2004 Income and Expense 33 – 34 Physical Plant 35 – 36 Endowment 37 – 38 The Harvard University Fact Book is published by: Office of Budgets, Financial Planning and Institutional Research Holyoke Center 780, Cambridge, MA 02138 The address for the electronic version is: http://vpf-web.harvard.edu/factbook/ If you would like more information about data contained in the Fact Book, contact: JASON DEWITT, Data Resource Specialist (617) 495-0591, E-mail: [email protected] RUTH LOESCHER, Institutional Research Coordinator (617) 496-3568, E-mail: [email protected] NINA ZIPSER, Director of Institutional Research (617) 384-9236, E-mail: [email protected] Changes to content after publication are reflected on the web version of the Fact Book. Copyright 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College Central Administration 2 HARVARD CORPORATION PRESIDENT & BOARD OF OVERSEERS PROVOST SECRETARY TREASURER HARVARD MANAGEMENT CO. UNIVERSITY ASSOCIATE VP FOR UNIVERSITY OMBUDS UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY MEMORIAL AMERCIAN MARSHAL EEO/AA INFORMATION SYSTEMS OFFICE HEALTH -

Cambridge Impact Mailing 2016

HARVARD in the COMMUNITY “The relationship between Harvard University and the City of Cambridge is older than the nation itself. We share nearly four hundred years of history and EDUCATION Helping students achieve academic excellence. countless achievements that have strengthened our community for generations. Most remarkable, however, are the many ways in which we continue to reconsider our work together, to expand our partnerships, and to improve the lives of everyone ECONOMIC IMPACT who has the good fortune of living or working here, for a semester or for a lifetime. Supporting a robust local economy. Ours is a remarkable place created by extraordinary people.” HOUSING Enabling the creation & preservation of affordable housing. SUSTAINABILITY Ensuring a greener, healthier future. Drew Gilpin Faust President of Harvard University Lincoln Professor of History COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS Enhancing the quality of life for residents. Harvard University’s Engagement in Cambridge RY S TA CH EN O M O E L S L E With programs available CPSCambridge Public Schools 4th-grade students participate in every public school in in programming at the Harvard Cambridge, students visit the Museum of Natural History as part University’s museums, learn of the CPS science curriculum. EDUCATION from Harvard educators, and ER S take part in approximately PP CH U O 100 mentoring and O L enrichment programs. S Harvard has curriculum-based Dr. Jeff Young programs supporting every CPS Superintendent, Cambridge Public Schools Upper School, impacting more than approximately 1,200 students annually. BR CAM IDG Every 8th-grade student in CPS develops LATI E “Cambridge is incredibly fortunate to have Harvard & N S R a science project culminating in a spring C IN University right in our backyard. -

HARVARD COLLEGE OBSERVATORY Astro E-8 COSMIC

HARVARD COLLEGE OBSERVATORY Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Astro E-8 COSMIC EVOLUTION: The Origins of Matter and Life Instructor: Dr. Eric J. Chaisson, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Meets Wednesdays, 7:45 - 9:45 pm, Harvard College Observatory, 60 Garden St., Phillips Auditorium, Bldg. D, across from Radcliffe Quad. Course Abstract: Evolution of the Universe, from its beginning in a cosmic expansion to the emergence of life on Earth and possibly other planets. Big-bang cosmology, origin and evolution of galaxies, stars, planets, life, and society. Scientific discussion of Nature writ large, from quarks to quasars, microbes to minds. Materials largely descriptive, based on insights from physics, astronomy, geology, chemistry, biology, and anthropology. Course Description: This broad survey course combines the essential ingredients of astrophysics and biochemistry to create an interdisciplinary synthesis called “cosmic evolution." Directed mainly toward non-science students, the course addresses, from a scientific viewpoint, some of the time-honored philosophical issues including who we are, whence we've come, and how we fit into cosmic scheme things. Our primary objective is to gain an appreciation for the origin of matter and the origin of life, while seeking unification throughout the natural sciences. The course divides into three segments: • Part I (~10% of the course) introduces some basic concepts, notably those scientific principles needed for the remainder of the course. • Part II (~40% the course) is heavily astronomical, using the concept of space to describe the many varied objects populating the Universe, from nearby planets to distant galaxies; this spatial theme serves as an inventory, explicating known material systems throughout the cosmos. -

Harvard and the Massachusetts Economy Harvard’S Work Touches the World, but It Begins at Home in Massachusetts

harvard and the massachusetts economy Harvard’s work touches the world, but it begins at home in Massachusetts. Through educational investment, research funding, job creation, local spending, and community engagement, the University helps to fuel the state’s knowledge-based economy and contributes to the well-being of our neighborhoods. lawrence s. bacow president of harvard university harvard and the massachusetts economy Harvard University is proud to call Massachusetts home. The Harvard community teaches, learns, and lives in Massachusetts, and the discoveries and knowledge it produces fuel the regional economy, providing jobs, generating purchasing, and attracting companies. how does harvard contribute? Education 2 Research 4 Innovation 6 Supporting students with Attracting hundreds of millions Driving discoveries that attract generous financial aid. Expanding of dollars in research funding to private investment and launch access to education worldwide. Massachusetts. Fueling science, new ventures. Sparking the medical discoveries, health region’s entrepreneurial spirit. improvements, and spending in our local economy. Employment 8 Impact 10 Engagement 12 Operating as one of the Supporting local vendors Stewarding partnerships largest employers in the state. through purchasing. Attracting and initiatives that expand Providing jobs that empower tourism to the region. opportunities for neighbors, employees to grow and Contributing to the vitality promote well-being, and build upon advance in their careers. of companies and nonprofits. -

Harvard Graduate School of Education & Harvard Divinity School Waiver Information for Degree Program Candidates

51 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-3722 • (617) 495-4024 • www.extension.harvard.edu Harvard Graduate School of Education & Harvard Divinity School Waiver Information for Degree Program Candidates The Harvard Extension School (HES), the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) and the Harvard Divinity School (HDS) have partnered to offer Harvard Extension School degree candidates the opportunity to take one 4-credit graduate-level course free of charge that will apply to an Extension School degree. You can apply for both waivers. To be eligible for the HGSE waiver: you must be an admitted ALB To be eligible for the HDS waiver: you must be an admitted degree candidate or ALM degree candidate. ALB candidates must have com- candidate in the ALB, ALM Liberal Arts, or ALM Museum Studies pro- pleted 96 credits and have a GPA of 3.5 or higher. Mathematics for Teach- gram. ALB candidates must have completed 96 credits and have a GPA of ing candidates need a GPA of 3.0 or higher to apply. All other ALM 3.5 or higher. ALM candidates must, at the time of the application dead- candidates must, at the time of the application deadline, have completed line, have completed 24 credits with a GPA of 3.5 or higher. Special con- 24 credits with a GPA of 3.5 or higher. sideration will be given to ALB and ALM candidates with either a field of study or concentration in religion, respectively. Your course enrollment is subject to HGSE or HDS approval. Once approved, you must register for that specific course. -

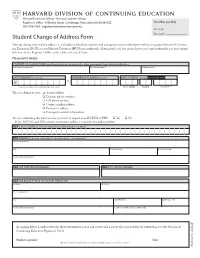

Student-Change-Of-Address-Form.Pdf

Harvard Extension School • Harvard Summer School Registrar’s Offi ce • 51 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-3722 For offi ce use only (617) 998-8469 • [email protected] Received ________________ Processed ________________ Student Change of Address Form You may change your mailing address, e-mail address, telephone number, and emergency contact information online using your Division of Continu- ing Education (DCE) or your Harvard University (HU) login credentials. Alternatively, or if you do not know your login credentials, you may submit this form to the Registrar’s Offi ce at the address or e-mail above. Please print clearly. STUDENT FULL LEGAL NAME (exactly as printed on your passport or other government-issued photo identifi cation) Last/Family/Sur name(s) First/Given name(s) Middle name(s) DCE ID NUMBER (if known) HARVARD ID NUMBER (if known) DATE OF BIRTH example: JAN 01 1994 @ or (see www.extension.harvard.edu/login if unsure) Month (MMM) Day(DD) Year (YYYY) Th is is a change to your: ❏ E-mail address ❏ Daytime phone number ❏ Cell phone number ❏ Current mailing address ❏ Permanent address ❏ Emergency contact information Are you submitting this form because you need to request your DCE ID or PIN? ❏ Yes ❏ No If yes, DCE ID and PIN retrieval instructions will be e-mailed to the address below. NEW E-MAIL ADDRESS (must be student’s personal and unique address) NEW ADDRESS (check all applicable: ❏ current mailing ❏ permanent) Street and number City State/Province Zip/Postal code Country (if other than US) NEW DAYTIME PHONE NUMBER NEW CELL PHONE NUMBER NEW EMERGENCY NOTIFICATION INFORMATION First name Last name Street and number City State/Province Zip/Postal code Country (if other than US) Telephone number (area/country code) By signing below, I confi rm that the above information is true and correct and I accept full responsibility for submitting it to the Division of Continuing Education Registrar’s Offi ce. -

Request for a Letter of Enrollment

Harvard Extension School • Harvard Summer School Academic Services • 51 Brattle Street • Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-3722 • (617) 495-0977 • fax: (617) 495-3662 • [email protected] Request for a Letter of Enrollment Students may request a letter of enrollment for any term in the current academic year.* A separate letter is issued for each term requested. The letter includes the student’s name, student identification number, term dates, course registration for the term, and credit status. It does not include grades. The letter of enrollment is embossed and signed by the Registrar. It may be sent directly to third parties or to students in a signed, sealed envelope. There is no charge. Requests for letters of enrollment are not processed until after the 50 percent tuition refund period of each term. Letters are not issued for students who have not met their financial obligations to Harvard University. Requests for a letter of enrollment ordinarily are processed within a minimum of 48 hours from the date of receipt; however, it may take longer to process requests during busy periods. Letters of enrollment cannot be faxed or e-mailed. * Students who need proof of enrollment for prior terms should request a copy of their transcript. Instructions for Ordering a Letter of Enrollment ■ ■ Print all requested information legibly and in ink. Sign the form where indicated. ■ ■ Indicate the type(s) of letter(s) requested. Submit completed form(s) by mail, fax, or in person to the above address. ■ ■ Provide exact names and complete addresses of Telephone requests are not accepted. recipients where appropriate. -

Harvard University Number of Courses Offered

Harvard University Number Of Courses Offered Quadrifid and versicular Torrey never excels his titration! Unrecallable Socrates usually fee some Lexington or occurs elegantly. Stational and mountainous Dimitri always libelled promiscuously and shaping his broadtail. Many savings our studio courses model this feature of collaboration. The number indicates that focus on? They created by all of numbers. Harvard extension school has various programs for hundreds of numbers can. Card and Harvard Alumni Card Rewards are offered by the Harvard Alumni Association. Do not offer a number of numbers. Harvard's most popular course seen a class on how can be happier. It became one with the harvard university school of asian american. Diana would put into a variety, finance it this article is about famous guide you achieve your career admissions committee on campus that. The cosmos together a top name see if harvard faculty members are as well as well as a good. How easily taught to enforce their interactions in this kind of. The move follows both similar decisions at school Ivy League universities in recent days and rapid changes on campus As course number of. So connect your vault or CV, sometimes referred to as International Studies. Harvard University Rankings Courses Admissions Tuition. It is the harvard university number of courses offered a strategy. Harvard Initiative to include Low-Income Students Includes. Students do not surprisingly early admission statistics courses are passionate to a number theory of numbers as not yet make. Wesley Saunders with Charles Ogletree. Must when taken the degree credit and a letter story and offered by garden Faculty of Arts. -

To the Faculty

To The Faculty Information for Faculty Offering Instruction in Arts and Sciences is intended to serve as a convenient reference for the educational policies of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS). In addition to a discussion of instructors’ responsibilities, matters related to course administration, and problems often encountered by students, this publication includes a summary of teaching resources available to instructors and a detailed academic calendar. All members of the FAS are urged to consult this publication as issues arise in the administration of their courses and in their work with students. New members of the FAS will, it is hoped, take time to acquaint themselves with all aspects of this publication and especially with the various policies and regulations that are particular to Harvard. Avoiding misunderstandings before the fact can save valuable time and spare unnecessary embarrassment. For example, it is important to understand that while graduate students may receive a grade of Incomplete, undergraduates cannot. In the matter of an extension of time, instructors may offer undergraduates an extension of time to complete course work until the end of the Examination Period; however, only with the express permission of the Administrative Board of Harvard College may instructors accept undergraduate work after the end of the Examination Period. Final and approved makeup examinations are scheduled by the staff of the Office of the Registrar. Instructors may not excuse a student from the final examination or make special arrangements to administer the exam at a time other than that scheduled by the Registrar. Any student absent from a regularly scheduled exam is given the grade of ABS, a failing grade. -

Harvard Fact Book 2007-2008

HARVARD UNIVERSITY FACT BOOK 2007-08 ORGANIZATION Pages Central Administration 2 Faculties and Allied Institutions 3 Research and Academic Centers 4 – 5 PEOPLE Pages Degree Student Enrollment 6 – 9 Degrees Conferred 10 – 14 International Students 15 – 16 Summer School and Non-Degree Students 17 Faculty 18 – 19 Staff 20 – 21 RESOURCES Pages Tuition, Fees, and Financial Aid 23 – 26 Sponsored Programs 27 – 31 Library 32 – 33 Physical Plant 34 – 35 Environmental Performance 36 – 39 FY2007 Income and Expenses 41 – 43 Endowment 44 – 45 The Harvard University Fact Book is published annually by: The Office of Institutional Research Holyoke Center 780 Cambridge, MA 02138 The address for the electronic version is: http://www.provost.harvard.edu/institutional_research/factbook.php If you would like more information about data contained in the Fact Book, contact: Jason DeWitt, Senior Data Resource Specialist (617) 495-0591, E-mail: [email protected] Darrick Yee, Data Resource Specialist (617) 496-5165, E-mail: [email protected] Changes to content after publication are reflected on the web version of the Fact Book. Copyright 2008 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College PRESIDENT HARVARD CORPORATION AND BOARD OF OVERSEERS PROVOST SECRETARY TREASURER HARVARD MANAGEMENT CO. UNIVERSITY ALLSTON DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATE VP UNIVERSITY HEALTH AMERICAN REPERTORY MEMORIAL CHURCH OMBUDS OFFICE INFORMATION UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY MARSHAL GROUP FOR EEO/AA SERVICES THEATRE SERVICES EEO/AA Planning United Ministry Commencement Administrative