The Anthropology of Sibling Relations Shared Parentage, Experience, and Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Adoption Sibling Visitation Dawn J

ARE YOU STILL MY FAMILY? POST-ADOPTION SIBLING VISITATION DAWN J. POST, ESQ., SARAH MCCARTHY, ESQ., ROGER SHERMAN, PH.D. AND SERVET BAYIMLI * I. INTRODUCTION On Kayla’s1 first birthday in July of 1998, she was placed into foster care following allegations that her seventeen-year-old mother neglected her. Kayla was initially placed with her mother in a city-operated home for teenagers with children.2 However, when her mother was no longer able to care for her, Kayla’s paternal grandmother took over as her foster mother.3 Soon after Kayla’s new placement, her mother gave birth to another baby, Copyright © 2015, Dawn J. Post, Esq., Sarah McCarthy Esq., Roger Sherman, Ph.D and Servet Bayimli. * We are practitioners in the child welfare field. Accordingly, much of what is written in this Article is our view of the situation as it currently stands. Also, the case examples mentioned contain confidential information for which citation cannot be provided. However, these cases were handled by or explained to us other attorneys, social workers, or participants in their respective cases. We are indebted to Executive Director Karen P. Simmons for her mentorship and support; Veronica Kapka and Latoya Lennard for their research and work on the narrative interviews; and CPIC Harvard fellows Allison Torsiglieri and Gene Young Chang for their insightful comments and editing. 1 Interview with Kayla, Adoptee, Children’s Law Center New York, in Brooklyn, N.Y. (Nov. 11, 2013) [hereinafter Kayla Interview] (unpublished) (on file with authors). From December 2013 through June 2014, the Children’s Law Center New York (CLCNY) conducted interviews of young people and adults who had experienced the loss of their sibling, as well as adoptive parents who had either encouraged or terminated sibling contact, and were solicited from LinkedIn or at conferences. -

American Cultural Anthropology and British Social Anthropology

Anthropology News • January 2006 IN FOCUS ANTHROPOLOGY ON A GLOBAL SCALE In light of the AAA's objective to develop its international relations and collaborations, AN invited international anthropologists to engage with questions about the practice of anthropology today, particularly issues of anthropology and its relationships to globaliza- IN FOCUS tion and postcolonialism, and what this might mean for the future of anthropology and future collaborations between anthropologists and others around the world. Please send your responses in 400 words or less to Stacy Lathrop at [email protected]. One former US colleague pointed out American Cultural Anthropology that Boas’s four-field approach is today presented at the undergradu- ate level in some departments in the and British Social Anthropology US as the feature that distinguishes Connections and Four-Field Approach that the all-embracing nature of the social anthropology from sociology, Most of our colleagues’ comments AAA, as opposed to the separate cre- highlighting the fact that, as a Differences German colleague noted, British began by highlighting the strength ation of the Royal Anthropological anthropologists seem more secure of the “four-field” approach in the Institute (in 1907) and the Associa- ROBERT LAYTON AND ADAM R KAUL about an affinity with sociology. US. One argued that this approach is tion of Social Anthropologists (in U DURHAM Clearly British anthropology traces in fact on the decline following the 1946) in Britain, contributes to a its lineage to the sociological found- deeper impact that postmodernism higher national profile of anthropol- ing fathers—Durkheim, Weber and consistent self-critique has had in the US relative to the UK. -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2004 The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships Allison Mercedes Caban University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Caban, Allison Mercedes, "The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2004. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1960 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Allison Mercedes Caban entitled "The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Psychology. Anne McIntyre, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Debora Baldwin, Cheryl Buehler, Kristina Coop-Gordon Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Allison Mercedes Caban entitled “The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships”. I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Psychology. -

Reciprocity and Social Capital in Sibling Relationships of People with Disabilities

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Massachusetts Boston: ScholarWorks at UMass SIBLINGS AND SOCIAL CAPITAL 1 RUNNING HEAD: SIBLINGS AND SOCIAL CAPITAL Title: Reciprocity and Social Capital in Sibling Relationships of People with Disabilities John Kramer, Ph.D. Institute for Community Inclusion, University of Massachusetts Boston Allison Hall, Ph.D. Institute for Community Inclusion, University of Massachusetts Boston Tamar Heller, Ph.D. Institute on Disability and Human Development, University of Illinois at Chicago As appeared in: John Kramer, Allison Hall, and Tamar Heller (2013) Reciprocity and Social Capital in Sibling Relationships of People With Disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: December 2013, Vol. 51, No. 6, pp. 482-495. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.6.482 SIBLINGS AND SOCIAL CAPITAL 2 Abstract Sibling relationships are some of the longest-lasting relationships people experience, providing ample opportunities to build connections across the lifespan. For siblings and people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD), these connections take on an increased significance as their families age and parents can no longer provide care. This paper presents findings from a qualitative study that addresses the question, “How do siblings support each other after parents no longer can provide care to the person with I/DD?” Findings in this study suggest that siblings with and without disabilities experience reciprocity as a transitive exchange, which occurs through the creation of social capital in their families and community, and that nondisabled siblings mobilize their social capital to provide support to their sibling after parents pass away. -

Dealing with Uncertainty: Shamans, Marginal Capitalism, and the Remaking of History in Postsocialist Mongolia

MANDUHAI BUYANDELGERIYN Harvard University Dealing with uncertainty: Shamans, marginal capitalism, and the remaking of history in postsocialist Mongolia ABSTRACT ore than 15 years have passed since the collapse of social- In this article, I explore the proliferation of ism in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and Mongolia.1 Most previously suppressed shamanic practices among people in these regions have been subjected to unexpected, ethnic Buryats in Mongolia after the collapse of contradictory, and often confusing transformations because socialism in 1990. Contrary to the Buryats’ of the “unmaking” (Humphrey 2002) of socialism and the si- expectation that shamanism would solve the Mmultaneous arrival of a market economy and implementation of neoliberal uncertainties brought about by the market economy, economic reforms. Because the economic transformations have been the it has created additional spiritual uncertainties. As most visible and pertinent aspects of the transitions to postsocialism, a rich skeptical Buryats repeatedly propitiate their angry body of work has discussed the restructuring of property and privatization, origin spirits to alleviate the causes of their state institutions, and the rethinking of political categories (Berdahl 1999; misfortunes, they reconstruct their history, which Borneman1992,1998;BurawoyandVerdery1999;Caldwell2004;Humphrey was suppressed by state socialism. The Buryats make 2002; Verdery 1996). Scholars elsewhere have also noted that the feelings of their current calamities meaningful by placing them uncertainty, insecurity, and anxiety that result from the dangerous volatil- within the shifting history of their tragic past. The ity, disorder, and opaqueness of the market are being articulated through sense of uncertainty, fear, and disillusionment the medium of popular religion, shamanism, witchcraft, and spirit posses- experienced by the Buryats also characterizes daily sion (Comaroff and Comaroff 2000; Kendall 2003; Moore and Sanders 2001; life in places other than Mongolia. -

Mathematical Modeling and Anthropology: Its Rationale, Past Successes and Future Directions

Mathematical Modeling and Anthropology: Its Rationale, Past Successes and Future Directions Dwight Read, Organizer European Meeting on Cybernetics and System Research 2002 (EMCSR 2002) April 2 - 5, 2002, University of Vienna http://www.ai.univie.ac.at/emcsr/ Abstract When anthropologists talk about their discipline as a holistic study of human societies, particularly non-western societies, mathematics and mathematical modeling does not immediately come to mind, either to persons outside of anthropology and even to most anthropologists. What does mathematics have to do with the study of religious beliefs, ideologies, rituals, kinship and the like? Or more generally, What does mathematical modeling have to do with culture? The application of statistical methods usually makes sense to the questioner when it is explained that these methods relate to the study of human societies through examining patterns in empirical data on how people behave. What is less evident, though, is how mathematical thinking can be part of the way anthropologists reason about human societies and attempt to make sense of not just behavioral patterns, but the underlying cultural framework within which these behaviors are embedded. What is not widely recognized is the way theory in cultural anthropology and mathematical theory have been brought together, thereby constructing a dynamic interplay that helps elucidate what is meant by culture, its relationship to behavior and how the notion of culture relates to concepts and theories developed not only in anthropology but in related disciplines. The interplay is complex and its justification stems from the kind of logical inquiry that is the basis of mathematical reasoning. -

Consanguinity, Sibling Relationships, and the Default Rules of Inheritance Law: Reshaping Half-Blood Statutes to Reflect the Evolving Family

SMU Law Review Volume 58 Issue 1 Article 6 2005 Consanguinity, Sibling Relationships, and the Default Rules of Inheritance Law: Reshaping Half-Blood Statutes to Reflect the Evolving Family Ralph C. Brashier Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Ralph C. Brashier, Consanguinity, Sibling Relationships, and the Default Rules of Inheritance Law: Reshaping Half-Blood Statutes to Reflect the vE olving Family, 58 SMU L. REV. 137 (2005) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol58/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. CONSANGUINITY, SIBLING RELATIONSHIPS, AND THE DEFAULT RULES OF INHERITANCE LAW: RESHAPING HALF-BLOOD STATUTES TO REFLECT THE EVOLVING FAMILY Ralph C. Brashier* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRO DUCTION ........................................ 138 II. BACKGROUND ........ ......................... 141 A. A "MODERN" LAW OUT OF TOUCH WITH THE M ODERN FAMILY ...................................... 141 B. THE ROLE OF DEFAULT RULES IN INHERITANCE L AW ..................................................... 144 C. THE IMPORTANCE OF HALF-BLOOD STATUTES ........ 148 D. DISTINGUISHING PARENTAL HOPES FROM SIBLING A TTITUDES .............................................. 150 III. SIBLING RELATIONSHIPS IN MODERN FA M IL IE S ................................................ 151 A. HALF-BLOOD RELATIONSHIPS ARISING FROM M ARRIAGE .............................................. 152 B. HALF-BLOOD RELATIONSHIPS ARISING OUTSIDE M ARRIAGE .............................................. 153 C. ATTENUATED HALF-BLOOD RELATIONSHIPS ........... 156 D. THE UNKNOWN HALF-SIBLING ......................... 158 IV. APPROACHES TO HALF-BLOODS AND IN H ERITA NCE .......................................... 161 A. INCLUSION ON AN (ALMOST) EQUAL BASIS ........... 163 B. -

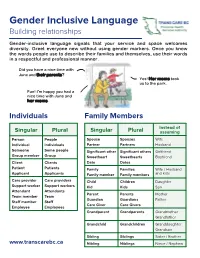

Gender Inclusive Language Building Relationships

Gender Inclusive Language Building relationships Gender-inclusive language signals that your service and space welcomes diversity. Greet everyone new without using gender markers. Once you know the words people use to describe their families and themselves, use their words in a respectful and professional manner. Did you have a nice time with June and their parents? Yes! Her moms took us to the park. Fun! I'm happy you had a nice time with June and her moms. Individuals Family Members Instead of Singular Plural Singular Plural assuming Person People Spouse Spouses Wife Individual Individuals Partner Partners Husband Someone Some people Significant other Significant others Girlfriend Group member Group Sweetheart Sweethearts Boyfriend Client Clients Date Dates Patient Patients Family Families Wife / Husband Applicant Applicants Family member Family members and kids Care provider Care providers Child Children Daughter Support worker Support workers Kid Kids Son Attendant Attendants Parent Parents Mother Team member Team Guardian Guardians Father Staff member Staff Care Giver Care Givers Employee Employees Grandparent Grandparents Grandmother Grandfather Grandchild Grandchildren Granddaughter Grandson Sibling Siblings Sister / Brother www.transcarebc.ca Nibling Niblings Niece / Nephew ii Pronouns (using they in the singular) If you are in a setting where your interactions with people are brief, you may not have time to get to know the person. Using the singular they in these situations can help to avoid pronoun mistakes. subject They They are waiting at the door. object Them The form is for them. possessive Their Their parents will pick them up at 3pm. adjective possessive Theirs They said the wheelchair is not theirs. -

Placement Process Resource Guide

Placement Process Resource Guide Updated September 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................................... i The Placement Process Overview ......................................................................................................... 1 Definition of Placement ........................................................................................................................ 1 Initial Placement .................................................................................................................................... 2 Short-Term Emergency Placements .................................................................................................... 2 Subsequent Placements ........................................................................................................................ 2 Placement Types and Definitions ......................................................................................................... 3 Own Home ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Substitute Care ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Regulated Foster Care........................................................................................................................... 4 Types of Regulated -

What Is Anthropology?

Chapter 1 What Is Anthropology? nthropology is the scientific study of the origin, the behaviour, and the A physical, social, and cultural development of humans. Anthropologists seek to understand what makes us human by studying human ancestors through archaeological excavation and by observing living cultures throughout the world. In this chapter, you will learn about different fields of anthropology and the major schools of thought, important theories, perspectives, and research within anthropology, as well as the work of influential anthropologists. You’ll also learn methods for conducting anthropological research and learn how to formulate your own research questions and record information. Chapter Expectations By the end of this chapter, you will: • summarize and compare major theories, perspectives, and research methods in anthropology • identify the significant contributions of influential anthropologists • outline the key ideas of the major anthropological schools of thought, and explain how they can be used to analyze features of cultural systems Fields of Anthropology • explain significant issues in different areas of anthropology Primatology Dian Fossey (1932–1985) • explain the main research methods for conducting anthropological Physical Anthropology Archaeology Cultural Anthropology research Biruté Galdikas (1946–) Jane Goodall (1934–) Sue Savage-Rumbaugh (1946–) Archaeology Forensic Human Variation Ethnology Linguistic Anthropology Key Terms Prehistoric Anthropology Charles Darwin Ruth Benedict (1887–1948) Noam Chomsky -

Aging Families—Series Bulletin #1 Sibling Relations in Later Life

Aging Families—Series Bulletin #1 Sibling Relations in Later Life Aging Family Relationships When we think about family life, often there is an assumption we are talking only about families with young children. There is also an assumed emphasis on immediate rather than extended relationships that consist of one generation. As a result of a dramatic increase in life expectancy and the subse- quent growth in the population of older adults, more attention is now being given to the many relationships among family mem- bers in later life. Researchers and educators interested in the dynamics of later life family relationships have developed new terms, for example, “aging families,” “later life mar- riage,” “skip-generation grandparents,” and the “sandwich generation.” In fact, an emerging sub-field within the field of Family Science, known as “Family Gerontology” (Blieszner & Bedford, 1997) is becoming increasingly recognized. This specialization area is specifically related to exploring and analyzing family relationships among older adults. Some of the roles and relationships that pertain to aging families in- clude grandparents and their grandchildren, aging parents and their adult children, later life marriages, divorce and remarriage among seniors, and siblings in later life. This is the first in a series of bulletins that will include information about the unique characteristics of later life family relationships. The focus of this particular publica- tion is sibling relationships among older adults. Libby and Rose Libby and Rose had been sisters for 76 planned her funeral together and spent years. They had grown up together on one week cleaning out the old house and an Iowa farm, sharing secrets, fighting dividing up family heirlooms.