Aging Families—Series Bulletin #1 Sibling Relations in Later Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Adoption Sibling Visitation Dawn J

ARE YOU STILL MY FAMILY? POST-ADOPTION SIBLING VISITATION DAWN J. POST, ESQ., SARAH MCCARTHY, ESQ., ROGER SHERMAN, PH.D. AND SERVET BAYIMLI * I. INTRODUCTION On Kayla’s1 first birthday in July of 1998, she was placed into foster care following allegations that her seventeen-year-old mother neglected her. Kayla was initially placed with her mother in a city-operated home for teenagers with children.2 However, when her mother was no longer able to care for her, Kayla’s paternal grandmother took over as her foster mother.3 Soon after Kayla’s new placement, her mother gave birth to another baby, Copyright © 2015, Dawn J. Post, Esq., Sarah McCarthy Esq., Roger Sherman, Ph.D and Servet Bayimli. * We are practitioners in the child welfare field. Accordingly, much of what is written in this Article is our view of the situation as it currently stands. Also, the case examples mentioned contain confidential information for which citation cannot be provided. However, these cases were handled by or explained to us other attorneys, social workers, or participants in their respective cases. We are indebted to Executive Director Karen P. Simmons for her mentorship and support; Veronica Kapka and Latoya Lennard for their research and work on the narrative interviews; and CPIC Harvard fellows Allison Torsiglieri and Gene Young Chang for their insightful comments and editing. 1 Interview with Kayla, Adoptee, Children’s Law Center New York, in Brooklyn, N.Y. (Nov. 11, 2013) [hereinafter Kayla Interview] (unpublished) (on file with authors). From December 2013 through June 2014, the Children’s Law Center New York (CLCNY) conducted interviews of young people and adults who had experienced the loss of their sibling, as well as adoptive parents who had either encouraged or terminated sibling contact, and were solicited from LinkedIn or at conferences. -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2004 The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships Allison Mercedes Caban University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Caban, Allison Mercedes, "The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2004. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1960 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Allison Mercedes Caban entitled "The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Psychology. Anne McIntyre, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Debora Baldwin, Cheryl Buehler, Kristina Coop-Gordon Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Allison Mercedes Caban entitled “The Effects of Marital Conflict on Sibling Relationships”. I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Psychology. -

Reciprocity and Social Capital in Sibling Relationships of People with Disabilities

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Massachusetts Boston: ScholarWorks at UMass SIBLINGS AND SOCIAL CAPITAL 1 RUNNING HEAD: SIBLINGS AND SOCIAL CAPITAL Title: Reciprocity and Social Capital in Sibling Relationships of People with Disabilities John Kramer, Ph.D. Institute for Community Inclusion, University of Massachusetts Boston Allison Hall, Ph.D. Institute for Community Inclusion, University of Massachusetts Boston Tamar Heller, Ph.D. Institute on Disability and Human Development, University of Illinois at Chicago As appeared in: John Kramer, Allison Hall, and Tamar Heller (2013) Reciprocity and Social Capital in Sibling Relationships of People With Disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: December 2013, Vol. 51, No. 6, pp. 482-495. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.6.482 SIBLINGS AND SOCIAL CAPITAL 2 Abstract Sibling relationships are some of the longest-lasting relationships people experience, providing ample opportunities to build connections across the lifespan. For siblings and people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD), these connections take on an increased significance as their families age and parents can no longer provide care. This paper presents findings from a qualitative study that addresses the question, “How do siblings support each other after parents no longer can provide care to the person with I/DD?” Findings in this study suggest that siblings with and without disabilities experience reciprocity as a transitive exchange, which occurs through the creation of social capital in their families and community, and that nondisabled siblings mobilize their social capital to provide support to their sibling after parents pass away. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Consanguinity, Sibling Relationships, and the Default Rules of Inheritance Law: Reshaping Half-Blood Statutes to Reflect the Evolving Family

SMU Law Review Volume 58 Issue 1 Article 6 2005 Consanguinity, Sibling Relationships, and the Default Rules of Inheritance Law: Reshaping Half-Blood Statutes to Reflect the Evolving Family Ralph C. Brashier Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Ralph C. Brashier, Consanguinity, Sibling Relationships, and the Default Rules of Inheritance Law: Reshaping Half-Blood Statutes to Reflect the vE olving Family, 58 SMU L. REV. 137 (2005) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol58/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. CONSANGUINITY, SIBLING RELATIONSHIPS, AND THE DEFAULT RULES OF INHERITANCE LAW: RESHAPING HALF-BLOOD STATUTES TO REFLECT THE EVOLVING FAMILY Ralph C. Brashier* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRO DUCTION ........................................ 138 II. BACKGROUND ........ ......................... 141 A. A "MODERN" LAW OUT OF TOUCH WITH THE M ODERN FAMILY ...................................... 141 B. THE ROLE OF DEFAULT RULES IN INHERITANCE L AW ..................................................... 144 C. THE IMPORTANCE OF HALF-BLOOD STATUTES ........ 148 D. DISTINGUISHING PARENTAL HOPES FROM SIBLING A TTITUDES .............................................. 150 III. SIBLING RELATIONSHIPS IN MODERN FA M IL IE S ................................................ 151 A. HALF-BLOOD RELATIONSHIPS ARISING FROM M ARRIAGE .............................................. 152 B. HALF-BLOOD RELATIONSHIPS ARISING OUTSIDE M ARRIAGE .............................................. 153 C. ATTENUATED HALF-BLOOD RELATIONSHIPS ........... 156 D. THE UNKNOWN HALF-SIBLING ......................... 158 IV. APPROACHES TO HALF-BLOODS AND IN H ERITA NCE .......................................... 161 A. INCLUSION ON AN (ALMOST) EQUAL BASIS ........... 163 B. -

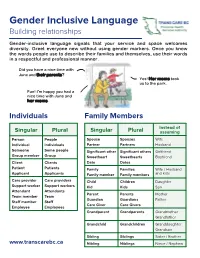

Gender Inclusive Language Building Relationships

Gender Inclusive Language Building relationships Gender-inclusive language signals that your service and space welcomes diversity. Greet everyone new without using gender markers. Once you know the words people use to describe their families and themselves, use their words in a respectful and professional manner. Did you have a nice time with June and their parents? Yes! Her moms took us to the park. Fun! I'm happy you had a nice time with June and her moms. Individuals Family Members Instead of Singular Plural Singular Plural assuming Person People Spouse Spouses Wife Individual Individuals Partner Partners Husband Someone Some people Significant other Significant others Girlfriend Group member Group Sweetheart Sweethearts Boyfriend Client Clients Date Dates Patient Patients Family Families Wife / Husband Applicant Applicants Family member Family members and kids Care provider Care providers Child Children Daughter Support worker Support workers Kid Kids Son Attendant Attendants Parent Parents Mother Team member Team Guardian Guardians Father Staff member Staff Care Giver Care Givers Employee Employees Grandparent Grandparents Grandmother Grandfather Grandchild Grandchildren Granddaughter Grandson Sibling Siblings Sister / Brother www.transcarebc.ca Nibling Niblings Niece / Nephew ii Pronouns (using they in the singular) If you are in a setting where your interactions with people are brief, you may not have time to get to know the person. Using the singular they in these situations can help to avoid pronoun mistakes. subject They They are waiting at the door. object Them The form is for them. possessive Their Their parents will pick them up at 3pm. adjective possessive Theirs They said the wheelchair is not theirs. -

Placement Process Resource Guide

Placement Process Resource Guide Updated September 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................................... i The Placement Process Overview ......................................................................................................... 1 Definition of Placement ........................................................................................................................ 1 Initial Placement .................................................................................................................................... 2 Short-Term Emergency Placements .................................................................................................... 2 Subsequent Placements ........................................................................................................................ 2 Placement Types and Definitions ......................................................................................................... 3 Own Home ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Substitute Care ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Regulated Foster Care........................................................................................................................... 4 Types of Regulated -

Japanese Children's Books 2020 JBBY's Recommendations for Young Readers Throughout the World

JAPANESE BOARD ON BOOKS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE Japanese 2020 Children's Books 2020 Cover illustration Japanese Children's Books Chiki KIKUCHI Born in 1975 in Hokkaido. After working at a design Contents firm, he decided at age 33 to become a picture book artist. His book Shironeko kuroneko (White ● Book Selection Team ................................................................................................2 Cat, Black Cat; Gakken Plus) won a Golden Apple ● About JBBY and this Catalog ................................................................................ 3 at the 2013 Biennial of Illustrations Bratislava (BIB), and his book Momiji no tegami (Maple Leaf Letter; ● Recent Japanese Children's Books Recommended by JBBY ......................4 Komine Shoten) won a plaque at the 2019 BIB. His ● The Hans Christian Andersen Award other works include Boku da yo, boku da yo (It’s Me, Five winners and 12 nominees from Japan It’s Me; Rironsha), Chikiban nyaa (Chiki Bang Meow; ........................................................20 Gakken Plus), Pa-o-po no uta (Pa-o-po Song; Kosei ● Japanese Books Selected for the IBBY Honour List ...................................22 Shuppan), Tora no ko Torata (Torata the Tiger Cub; Children’s Literature as a Part of Japan’s Publishing Statistics ....................... Shogakukan), and Shiro to kuro (White and Black; ● Essay: 24 Kodansha). ● Recent Translations into Japanese Recommended by JBBY ....................26 JBBY Book Selection and Review Team The JBBY Book Selection and Review Team collaboratively chose the titles listed in this publication. The name in parentheses after each book description is the last name of the team member who wrote the description. Yasuko DOI Director and senior researcher at the International Insti- Yukiko HIROMATSU tute for Children’s Literature (IICLO). Besides researching Picture book author, critic, and curator. -

Bereavement Leave

STATE OF CALIFORNIA - DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SERVICE PERSONNEL OPERATIONS MANUAL SUBJECT: BEREAVEMENT LEAVE REPRESENTED EMPLOYEES Bereavement leave allows for up to three (3) eight-hour days (24 hours) per occurrence or three (3) eight-hour days (24 hours) in a fiscal year based on the family member. The following chart describes the family member and bereavement leave allowed per bargaining unit. Bargaining Unit Eligible family member - three (3) eight-hour days Eligible family member - three (3) (24 hours) per occurrence eight-hour days (24 hours) in a fiscal year 1, 4, 11, 14, 15 • Parent • Aunt • Stepparent • Uncle • Spouse • Niece • Domestic Partner • Nephew • Child • immediate family members of • Grandchild Domestic Partners • Grandparent • Brother • Sister • Stepchild • Mother-in-Law • Father-in-Law • Daughter-in-Law • Son-in-Law • Sister-in-Law • Brother-in-Law • any person residing in the immediate household 2 • Parent • Grandchild • Stepparent • Grandparent • Spouse • Aunt • Domestic Partner • Uncle • Child • Niece • Sister • Nephew • Brother • Mother-in-Law • Stepchild • Father-in-Law • any person residing in the immediate household • Daughter-in-Law • Son-in-Law • Sister-in-Law • Brother-in-Law • immediate family member 7 • Parent • Grandchild • Stepparent • Grandparent • Spouse • Aunt • Domestic Partner • Uncle STATE OF CALIFORNIA - DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SERVICE PERSONNEL OPERATIONS MANUAL Bargaining Unit Eligible family member - three (3) eight-hour days Eligible family member - three (3) (24 hours) per occurrence eight-hour -

Brother Correlations in Income for Swedish Men Born 1932 - 1968

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Björklund, Anders; Jäntti, Markus; Lindquist, Matthew J. Working Paper Family background and income during the rise of the welfare state: brother correlations in income for Swedish men born 1932 - 1968 IZA Discussion Papers, No. 3000 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Björklund, Anders; Jäntti, Markus; Lindquist, Matthew J. (2007) : Family background and income during the rise of the welfare state: brother correlations in income for Swedish men born 1932 - 1968, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 3000, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/34319 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Ten Myths and Realitiesof Sibling Adoption

Ten Myths and Realities of Sibling Adoption Myth: When a child is acting in the parental role, he/ Myth: There are insufficient numbers of homes she should be separated from younger siblings to that have the willingness or capacity to parent give him/her a chance to “be a child” and/or reduce large sibling groups. 1interference with the new adult parent. 7 Reality: Most waiting families registered on AdoptUsKids Reality: Separating the older child is detrimental to both that child (83%) are willing to adopt more than one child. (McRoy 2010) and the younger children. The younger children must face life in Some adoptive families express the desire to adopt “ready unfamiliar circumstances without the support of the older child, made” families of sibling groups. Other larger families are and the older child is often left feeling responsible for the younger willing to adopt larger sibling groups. Policies and procedures siblings even when they are not placed together. Adoptive families that provide exceptions and incentives for families who adopt who are prepared to deal with this dynamic can help these siblings siblings groups are essential. develop appropriate roles. Myth: Potential adoptive families are less likely Myth: Brothers and sisters should be separated to express interest in children who are featured in to prevent sibling rivalry especially when there is recruitment efforts as members of sibling groups. extreme conflict. 8 2 Reality: Recruitment efforts specifically designed for sibling Reality: Separating siblings teaches them to walk away from groups that include: resource families who have raised siblings conflict and increases the trauma they already feel in being to recruit and talk to potential families; the use of media to separated from all that is familiar to them.