Wireless Emergency Alerts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Emergency Planning in NYC Toolkit

Community Emergency Planning in NYC A Toolkit for Community Leaders Introduction Emergency response in New York City is often challenged by the complexity of our physical and social environment. Communities are best understood by their own residents — a fact that makes community-based emergency planning and response highly effective. Each year, New York City experiences emergencies of all shapes and sizes. With aging infrastructure, higher frequency of natural disasters, and threats of terrorism, New York City is increasingly vulnerable. History and research have shown that communities that understand how to leverage internal networks are more successful in using their own resources and ultimately respond more effectively to their communities’ needs. The purpose of this toolkit to help your community become more resilient through a process of identifying existing networks, building new connections, and increasing your capacity to organize internal and external resources. Create a plan with your community now so that you are better prepared for the next emergency. WHAT IS IN THIS TOOLKIT? • New York City specific guidance for emergency planning. • A plan template and scenarios for Match communities to develop their own Community emergency plan. Community Resources to Needs Community Needs • Examples of other community Resources emergency planning efforts. Community Emergency WHO IS IT FOR? Planning This toolkit is designed to be a Coordinate Communicate group process. You define your own Planning and Needs and community — successful planning has Recovery Resources been done by housing developments, congregations, neighborhoods, etc. Examples of groups that could use the toolkit include: Government Resources • Tenant or civic associations • Faith-based groups • Community Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) • Community-based organizations (CBOs) • Community boards/coalitions 1 COMMUNITY EMERGENCY PLANNING LET’S GET STARTED! Your first step is to form a “lead team” — a group of interested community members who are willing to commit time and energy to this effort. -

Hurricane Sandy After Action Report and Recommendations

Hurricane Sandy After Action Report and Recommendations to Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg May 2013 Deputy Mayor Linda I. Gibbs, Co-Chair Deputy Mayor Caswell F. Holloway, Co-Chair Cover photo: DSNY truck clearing debris Credit: Michael Anton Foreword On October 29, 2012 Hurricane Sandy hit New York City with a ferocity unequalled by any coastal storm in modern memory. Forty-three New Yorkers lost their lives and tens of thousands were injured, temporarily dislocated, or entirely displaced by the storm’s impact. Knowing the storm was coming, the City activated its Coastal Storm Plan and Mayor Bloomberg ordered the mandatory evacuation of low-lying coastal areas in the five boroughs. Although the storm’s reach exceeded the evacuated zones, it is clear that the Coastal Storm Plan saved lives and mitigated what could have been significantly greater injuries and damage to the public. The City’s response to Hurricane Sandy began well before the storm and continues today, but we are far enough away from the immediate events of October and November 2012 to evaluate the City’s performance to understand what went well and—as another hurricane season approaches—what can be improved. On December 9, 2012 Mayor Bloomberg directed us to conduct that evaluation and report back in a short time with recommendations on how the City’s response capacity and performance can be strengthened in the future. This report and the 59 recommendations in it are intended to advance the achievement of those goals. This report is not intended to be the final word on the City’s response to Hurricane Sandy, nor are the recommendations made here intended to exclude consideration of additional measures the City and other stakeholders could take to be prepared for the next emergency. -

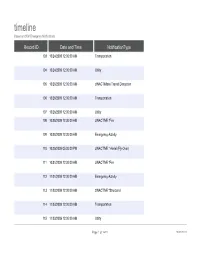

Timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications

timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications Record ID Date and Time NotificationType 103 10/24/2009 12:00:00 AM Transportation 104 10/24/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility 105 10/26/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIMass Transit Disruption 106 10/26/2009 12:00:00 AM Transportation 107 10/26/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility 108 10/28/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Fire 109 10/28/2009 12:00:00 AM Emergency Activity 110 10/29/2009 05:00:00 PM zINACTIVE * Aerial (Fly-Over) 111 10/31/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Fire 112 11/01/2009 12:00:00 AM Emergency Activity 113 11/02/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Structural 114 11/03/2009 12:00:00 AM Transportation 115 11/03/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility Page 1 of 1419 10/02/2021 timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications Notification Title [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] Major Gas Explosion 32-25 Leavitt St. [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] Page 2 of 1419 10/02/2021 timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications Email Body Notification 1 issued on 10/24/09 at 11:15 AM. Emergency personnel are on the scene of a motor vehicle accident involving FDNY apparatus on Ashford Street and Hegeman Avenue in Brooklyn. Ashford St is closed between New Lots Ave and Linden Blvd. Hegeman Ave is closed from Warwick St to Cleveland St. Notification 1 issued 10/24/2009 at 6:30 AM. Emergency personnel are on scene at a water main break in the Fresh Meadows section of Queens. -

Emergency Management Magazine May 2009

May/June 2009 inside: New York City’s Bruno opens up Where will stimulus money land? Nonprofi t collaboration COLLEGE CAMPUSES PREPARE FOR THE ON INEVITABLE PANDEMIC Issue 3 — Vol. 4 3 — Vol. Issue EEM05_cover.inddM05_cover.indd 1 ALERT 44/30/09/30/09 11:30:02:30:02 PPMM 100 Blue Ravine Road Designer Creative Dir. Folsom, CA 95630 916-932-1300 Editorial Prepress ���� ������� ������ ����� � PAGE ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� Other OK to go GIS—Providing You the Geographic Advantage™ Delivering Actionable Information Transform Your Data into Actionable Information During a crisis, emergency managers receive data from numerous sources. The challenge is fusing this data into something that can be quickly understood and shared for effective decision support. ESRI’s GIS technology provides you with the capability to quickly assimilate, analyze, and create actionable information. GIS aids emergency management by 4 Rapidly assessing impacts to critical infrastructure 4 Determining evacuation needs including shelters and appropriate routing 4 Directing public safety resources 4 Modeling incidents and analyzing consequences 4 Providing dynamic situational awareness and a common operating picture GIS is used to model the spread and intensity of a chemical spill. 4 Supplying mobile situational awareness to remote field teams Real-time weather data is used to determine the plume’s spread, direction, and speed. Discover more public safety case studies at www.esri.com/publicsafety. Copyright © 2009 ESRI. All rights reserved. The ESRI globe logo, ESRI, ESRI—The GIS Company, The Geographic Advantage, and www.esri.com, are trademarks, registered trademarks, or service marks of ESRI in the United States, the European Community, or certain other jurisdictions. -

January 6Th to 18Th, 2014 Cambridge, Boston & New York

URBAN ADAPTATION TO CLIMATE CHANGE: RESILIENT CITIES COLLABORATIVE FIELD COURSE IN THE USA January 6th to 18th, 2014 Cambridge, Boston & New York Academic Host Institutions School of Engineering & Escola Politécnica da David Rockefeller Center for Applied Sciences Universidade de São Paulo Latin American Studies (SEAS) (Poli-USP) (DRCLAS) Field Sites & Collaborating Institutions v Added Value & Red Hook Community; v NYC Office of Emergency Management; v Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; v NYC Mayor’s Office of Long-term Planning & v Center for Health and the Global Environment; Sustainability; v EnerNOC; v NYC Metropolitan Transportation Authority; v Exuma Lab; v Regional Plan Association; v Harvard Graduate School of Design; v Stephen M. Lawlor Medical Intelligence Center; v Harvard Innovation Lab; v Zofnas Program for Sustainable Infrastructure; v Harvard School of Public Health; v 9/11 Memorial. v MWRA’s Deer Island Sewage Treatment Plant; Support In addition to the support of the academic host institutions, this collaborative course was made possible thanks to the generosity of Claudio Haddad, Fundação Centro Tecnológico de Hidráulica, and the Lemann Family Endowment. http://brazil.drclas.harvard.edu Dear Participants (Caros Participantes), Welcome to the fifth edition of the Harvard/Poli-USP collaborative environmental engineering field course! This initiative is a joint effort of Harvard University’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), the Universidade de São Paulo’s Escola Politécnica (Poli-USP) and the Brazil Office of Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS). Following last year’s course in Brazil, we are excited to host our USP colleagues in Cambridge, Boston and New York City. -

BRONX Safety Plan

Ruben Beltran, Commanding Officer Mark Rampersant, Senior Executive Director School Safety Division Office of Safety and Youth Development New York City Police Department I.S. 216 - BRONX Safety Plan Academic Year: 2020-2021 Being Edited Print Date: August 28, 2020 12:52 PM Precinct: 041 PCT PBBX Address Information Street Address: 977 FOX STREET City/State/Zip: BRONX, NY 10459 Borough Safety Director Borough Safety Director: Sam Abbassi Building Council School Person Name Primary Contact Information 1 This plan contains confidential information and should not be posted online, reproduced, or distributed, except in cases of emergency. Print Date: Aug 28, 2020 12:52:50 PM Contents Section Topic Section 1 School Safety Agent School Safety Post Instructions Official Radio Codes School Safety Agent Post Assignment Form Section 2 Buildings Information Building Name Street Address I.S. 216 - BRONX, 977 FOX STREET For each building: □ General Building Information □ Accessibility □ Elevators □ Escalators □ Electromagnetic Locks □ Stairwells □ Vaults □ Pools □ Control Panel □ School Yard □ Intrusion Alarm □ CCTV/Video Surveillance Section 3 Other Facilities Information Transportables Cafeterias Section 4 Critical Security Notifications and Offices Section 5 School/Program/Academy Information Location Name plus School Name Accion Academy (12X341) School of Performing Arts (12X217) South Bronx Classical Charter School (84X346) For each school / program: □ Principal □ Operational Information □ Staff & Offices □# Students per Grade □ School Personnel -

How the Supreme Court's Decision Impacts Landlords

VolumeVol.Volume 66, No. 65,65, 80 No.No. 207207 MONDAY,MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARYFEBRUARY AUGUST 6,10,10, 2020 20202020 50¢ A tree fell across wires in Queens Village, knocking out power and upending a chunk of sidewalk. VolumeQUEENSQUEENS 65, No. 207 LIGHTSMONDAY, OUT FEBRUARY 10, 2020 Photo by Teresa Mettela 50¢ 57,000 QueensQueensQueens residents lose power Vol.Volume 66, No. 65, 80 No. 207 MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARY AUGUST 6,10, 2020 2020 50¢ VolumeVolumeVol.VolumeVol.VolumeVolume 66,67,66, 65, No. No. 65, 65,65,65, No. 80 9280No. No.No.No. 207 207 207207 MONDAY,MONDAY,MONDAY,THURSDAY,TUESDAY FEBRUARY FEBRUARYFEBRUARY, AUGUST AUGUST 10,24, 6,10,10, 202120202020 20202020 50¢50¢50¢ Vol.Volume 66, No. 65, 80 No. 207 MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARY AUGUST 6,10, 2020 2020 50¢ VolumeTODAY 65, No. 207 MONDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2020 AA tree tree fell fell across across wires wires in50¢ in TODAY A tree fell across wires in TODAY Vax mandates begin, legal challengesQueens QueensQueensto Village, followVillage, Village, knocking knocking knocking outout power power and and upending upending By Jacob Kaye Aout tree apower chunkfell across and of sidewalk. upending wires in Queens Daily Eagle a chunka Photochunk byof Teresaofsidewalk. sidewalk. Mettela VolumeQUEENS 65, No. 207 LIGHTSMONDAY, OUT FEBRUARY 10, 2020 QueensPhoto Village, by Teresa knocking Mettela 50¢ VolumeQUEENSQUEENS 65, No. 207 LIGHTSduring intenseMONDAY, OUT FEBRUARY 10, 2020 Photo by Teresa Mettela 50¢ Volume 65, No. 207 The U.S. Food and Drug AdministrationMONDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2020 50¢ QUEENSQUEENSQUEENS LIGHTS57,000 QueensQueens OUT out power and upending fully57,000 approved Queens Pfizer-BioNTech’sQueensQueensQueens COVID-19 a chunk of sidewalk. -

Preliminary Mayor's Management Report;

PRELIMINARY MAYOR’S MANAGEMENT REPORT FEBRUARY 2011 City of New York Michael R. Bloomberg Mayor Stephen Goldsmith Deputy Mayor for Operations Elizabeth Weinstein Director Mayor’s Office of Operations Cover Image: The Roses, Will Ryman, artist, Park Avenue and 61st Street. Photograph by NYC Parks & Recreation, Art & Antiquities, January 2011. Transforming the Park Avenue streetscape into a garden between 57th and 67th Streets, artist Will Ryman’s 38 sculptures of rose blossoms tower as high as 25 feet and are complemented by 20 individual scattered rose petals. Reflecting Ryman’s flair for the dramatic, roses painted in shades of pink and red spring up in vibrant contrast to the traditionally dormant winter months. Sponsored by the NYC Parks & Recreation and the Paul Kasmin Gallery, this temporary installation is on view until May 31, 2011. For more information, please visit www.nyc.gov or call 311. THE MAYOR’S MANAGEMENT REPORT PRELIMINARY FISCAL 2011 City of New York Michael R. Bloomberg, Mayor Stephen Goldsmith Deputy Mayor for Operations Elizabeth Weinstein Director, Mayor’s Office of Operations February 2011 8 Printed on paper containing 30% post consumer material. TABLE OF CONTENTS MMR User’s Guide ...................................................................ii Introduction ........................................................................vii HEALTH,EDUCATION AND HUMAN SERVICES DepartmentofHealthandMentalHygiene..............................................3 Office of Chief Medical Examiner .................................................9 -

Ready New York My Emergency Plan

READY NEW YORK MY EMERGENCY PLAN COVID-19 CONSIDERATIONS INCLUDED Emergency Department for Mayor’s Office for Management the Aging People with Disabilities 1 MY INFORMATION Please print. If viewing as a PDF, click on the highlighted areas to type in the information. Name: Address: Day Phone: Evening Phone: Cell Phone: Email: There are three basic steps to being prepared for any emergency: MAKE A PLAN GATHER SUPPLIES GET INFORMED Think about how emergencies may affect you. Emergencies can range from falls in the home to house fires to hurricanes. Use this guide now to list what you might need during an emergency. Please fill out the sections that apply to you and your needs. You can also download and complete this plan on the Ready NYC app for Android and iOS devices. Visit NYC.gov/readyny to access additional emergency preparedness materials, including the Ready New York: What’s Your Plan? video series. 3 MAKE A CREATE AN EMERGENCY PLAN SUPPORT NETWORK Don’t go through an emergency alone. Ask at least two people to be in your emergency support network — family members, friends, neighbors, caregivers, coworkers, or members of community groups. Remember, you can help and provide comfort to each other in emergencies. Your network should: Stay in contact during an emergency. Know where to find your emergency supplies. Know how to operate your medical equipment or help Allergies: move you to safety in an emergency. Other medical conditions: Emergency support network contacts: Name/Relationship: Essential medications and daily doses: Phone (home/work/cell): Email: Eyeglass prescription: Name/Relationship: Blood type: Phone (home/work/cell): Communication devices: Email: Equipment: Health insurance plan: Pick an out-of-area friend or relative who family or friends can call during a disaster. -

New York City Office of Emergency Management Joseph F. Bruno, Commissioner 1 Table of Contents

New York City Office of Emergency Management Joseph F. Bruno, Commissioner 1 Table of Contents HYPERLINK FEATURE PREPWhereverARING there is a handFOR cursor icon, 2009 you can click to get more information H1N1 onINFLUENZA that subject online. nt first detected the H1N1 virus in New York City when a large pg.1 Introduction: Commissioner’s Letter pg.2 Plan and Prepare for Emergencies pg.10 Educate the Public About Preparedness pg.14 Coordinate Emergency Response and Recovery pg.18 Collect and Disseminate Critical Information pg.22 Seek Funding to Support the Overall Preparedness of NYC Introduction: Commissioner’s Letter Dear Fellow New Yorkers, New York City is a complex place. Aging infrastructure and a growing population make the potential for emergencies a matter of routine. The rapid development and bustle of the city creates confusion even in the airspace above the city. The Office of Emergency Management (OEM), with its 24-hour Watch Command, remains vigilant and prepared to respond and bring all of the needed resources of this great city to any emergencies that may affect us. This is OEM’s third report, covering July 2007 to November 2009, and we have made it digital to align our actions with Mayor Bloomberg’s campaign for a greener New York City. In spring 2009, a new strain of the H1N1 flu virus surfaced in New York City. Fortunately, OEM and the Health Department had the City’s Pandemic Flu Plan prepared and had already developed a pandemic flu guide. The Health Department, Department of Education, OEM, and many other agencies worked together to develop a massive response to prepare for the likely return of the H1N1 virus in fall 2009. -

Emergency Contingency Plan

We suggest that you print this message Senior Staff Communication Plan More Resources and keep a copy at home. Each office has a communication plan to New York City Emergency Management NYC.gov/oem HPD Emergency Event Contact reach their employees. Phone Numbers (For Employees) Notify NYC Register for emergency notifications by EMERGENCY Please make sure your personal contact visiting NYC.gov, calling 311, downloading the Primary: (212) 863-5900 information is up to date. You may login to mobile app at NYC.gov/notifynycapp or Backup: (646) 879-5816 ESS to do so. following @NotifyNYC on Twitter. CONTINGENCY NYC Community Emergency Response In the event of an emergency please call Our contingency plans aim to preserve our Team (CERT) Program NYC.gov/CERT PLAN the primary number for a recorded computer systems, key functions, and office locations. announcement and instructions. In case the NYC Citizen Corps Council primary number is not functioning, please NYC.gov/citizencorps Evacuation Information use the backup number. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) If you are asked to evacuate any one of www.ready.gov Outside the Agency Only www.fema.gov HPD's buildings, please do so. Each office WWW.HPDNYC.ORG is available for HPD has a re-assembly point that you should go National Weather Service www.weather.gov employee online services from home or to post-evacuation. anywhere outside the agency. New York State Division of Homeland Re-Assembly Points: Security and Emergency Services www.dhses.ny.gov WWW.HPDNYC.ORG should be functional 100 Gold Street - Drumgoole Plaza during most types of emergencies as well as 105 East 106th Street - Parking lot at 107th NYC Service be available anytime for normal daily use and Park Avenue NYC.gov/volunteer 94 Old Broadway - Across the street on from your home PC or laptop.