The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hans Ulrich Obrist a Brief History of Curating

Hans Ulrich Obrist A Brief History of Curating JRP | RINGIER & LES PRESSES DU REEL 2 To the memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, Walter Hopps, Pontus Hultén, Jean Leering, Franz Meyer, and Harald Szeemann 3 Christophe Cherix When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked the former director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Anne d’Harnoncourt, what advice she would give to a young curator entering the world of today’s more popular but less experimental museums, in her response she recalled with admiration Gilbert & George’s famous ode to art: “I think my advice would probably not change very much; it is to look and look and look, and then to look again, because nothing replaces looking … I am not being in Duchamp’s words ‘only retinal,’ I don’t mean that. I mean to be with art—I always thought that was a wonderful phrase of Gilbert & George’s, ‘to be with art is all we ask.’” How can one be fully with art? In other words, can art be experienced directly in a society that has produced so much discourse and built so many structures to guide the spectator? Gilbert & George’s answer is to consider art as a deity: “Oh Art where did you come from, who mothered such a strange being. For what kind of people are you: are you for the feeble-of-mind, are you for the poor-at-heart, art for those with no soul. Are you a branch of nature’s fantastic network or are you an invention of some ambitious man? Do you come from a long line of arts? For every artist is born in the usual way and we have never seen a young artist. -

Poetic Voices of the Shoah Traumatic Memories and the Attempt to Express the Inexpressible

Department of Literary Studies Leiden University MA Literature in Society. Europe and Beyond. Supervision by Prof. Dr. Anthonya Visser Spring / Summer 2018 Master Thesis Poetic Voices of the Shoah Traumatic Memories and the Attempt to Express the Inexpressible Franca Maximiliane Schwab 1 Table of Content 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 State of Research.......................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 7 2. Trauma and Literature ..................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 The Controversy about Representing Trauma in Literature ........................................................ 9 2.2 Understanding Trauma .............................................................................................................. 10 2.3 The Force to Remember and the Effect of Repetition as Lyrical Device.................................. 12 3. Testifying and its Importance ........................................................................................................ 14 3.1 Poetic Testimony and its Risk ................................................................................................... 15 3.2 Poetry as a Surviving -

Ehri Newsletter

Ehri Newsletter EHRI Newsletter - Second Issue, April 2013 e-Newsletter for Experts in Holocaust Documentation Welcome to the second issue of the e-Newsletter for Experts in Holocaust Documentation, facilitated and developed as part of the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI). The aim of the newsletter is to share and disseminate knowledge and new insights, and to organize a continuous exchange of knowledge and views between experts in methodological fields of Holocaust research. This newsletter represents an additional complementary networking channel to the Expert Workshop, "Truth and Witness: An International Workshop on Holocaust Testimonies". We hope you find this issue interesting and resourceful, and we look forward to your feedback. Issue in Focus - Holocaust Testimonies Remembering Forced Labour. A Digital Interview Archive - Jan The International Database of Oral History Testimonies Rietema at USHMM - Neal Guthrie “Forced Labor 1939-1945” commemorates the more than twelve million The USHMM online International Database of Oral History people who were forced to work for Nazi Germany. Nearly 600 former Testimonies is the latest version of the Museum’s efforts to forced laborers from 26 countries tell their life stories in detailed audio provide as much information as possible about the vast and and video interviews. The interviews have been made accessible in an disparate collections of Holocaust oral histories and includes online archive at www.zwangsarbeit-archiv.de. Sophisticated retrieval 139 organizations—from museums and universities to local tools enhance a user-friendly research and a close-to-the-source analysis of the interview community organizations—in 21 countries, representing at least 115,000 recordings. -

Polysèmes, 19 | 2018 Photography and Trauma: an Introduction 2

Polysèmes Revue d’études intertextuelles et intermédiales 19 | 2018 Photography and Trauma Photography and Trauma: An Introduction Laurence Petit and Aimee Pozorski Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/polysemes/3366 DOI: 10.4000/polysemes.3366 ISSN: 2496-4212 Publisher SAIT Electronic reference Laurence Petit and Aimee Pozorski, « Photography and Trauma: An Introduction », Polysèmes [Online], 19 | 2018, Online since 30 June 2018, connection on 23 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/polysemes/3366 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/polysemes.3366 This text was automatically generated on 23 September 2020. Polysèmes Photography and Trauma: An Introduction 1 Photography and Trauma: An Introduction Laurence Petit and Aimee Pozorski His mother wrapped him up in a shawl and gave him a passport photograph of herself as a student. She told him to turn to the picture whenever he felt the need to do so. His parents both promised him that they would come and find him and bring him home after the war. (Dori Laub 1992) Survival, testimony, and witness 1 The 1992 coauthored collection Testimony by Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub became a groundbreaking work in trauma studies largely due to its ability to situate trauma within a post-World War II context that, they argued, continued to struggle to bear witness to the atrocity of the Holocaust. Cognizant of the powerful courtroom testimonies of survivors of the Holocaust—the Nuremberg Trials (1945-1946) and the Eichmann Trial in Jerusalem (1961-1962) among the two most notable—Felman and Laub link such key terms as testimony, witness, ethics, justice, and history to a growing field of trauma studies after the war. -

Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984)

1 de 2 SCULPTOR NINA SLOBODINSKAYA (1898-1984). LIFE AND SEARCH OF CREATIVE BOUNDARIES IN THE SOVIET EPOCH Anastasia GNEZDILOVA Dipòsit legal: Gi. 2081-2016 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/334701 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution licence TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898 -1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 Programa de doctorat: Ciències humanes I de la cultura Dirigida per: Dra. Maria-Josep Balsach i Peig Memòria presentada per optar al títol de doctora per la Universitat de Girona 1 2 Acknowledgments First of all I would like to thank my scientific tutor Maria-Josep Balsach I Peig, who inspired and encouraged me to work on subject which truly interested me, but I did not dare considering to work on it, although it was most actual, despite all seeming difficulties. Her invaluable support and wise and unfailing guiadance throughthout all work periods were crucial as returned hope and belief in proper forces in moments of despair and finally to bring my study to a conclusion. My research would not be realized without constant sacrifices, enormous patience, encouragement and understanding, moral support, good advices, and faith in me of all my family: my husband Daniel, my parents Andrey and Tamara, my ount Liubov, my children Iaroslav and Maria, my parents-in-law Francesc and Maria –Antonia, and my sister-in-law Silvia. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Arts, Fine of Museum The μ˙ μ˙ μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2013–2014 THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON, WARMLY THANKS THE 1,183 DOCENTS, VOLUNTEERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE MUSEUM’S GUILD FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY DEDICATION AND COMMITMENT. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2013–2014 Cover: GIUSEPPE PENONE Italian, born 1947 Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012 Bronze with gold leaf 433 1/16 x 96 3/4 x 79 in. (1100 x 245.7 x 200.7 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.728 While arboreal imagery has dominated Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures across his career, monumental bronzes of storm- blasted trees have only recently appeared as major themes in his work. Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012, is the culmination of this series. Cast in bronze from a willow that had been struck by lightning, it both captures a moment in time and stands fixed as a profoundly evocative and timeless monument. ALG Opposite: LYONEL FEININGER American, 1871–1956 Self-Portrait, 1915 Oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (100.3 x 80 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.756 Lyonel Feininger’s 1915 self-portrait unites the psychological urgency of German Expressionism with the formal structures of Cubism to reveal the artist’s profound isolation as a man in self-imposed exile, an American of German descent, who found himself an alien enemy living in Germany at the outbreak of World War I. -

Download (1233Kb)

Original citation: Koinova, Maria and Karabegovic, Dzeneta . (2016) Diasporas and transitional justice : transnational activism from local to global levels of engagement. Global Networks (Oxford): a journal of transnational affairs . Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/83210 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: "This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Koinova, Maria and Karabegovic, Dzeneta . (2016) Diasporas and transitional justice : transnational activism from local to global levels of engagement. Global Networks (Oxford): a journal of transnational affairs ., which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/glob.12128 This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving." A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. -

Exhibition Provides New Insight Into the Globalization of Conceptual Art, Through Work of Nearly 50 Moscow-Based Artists Thinki

EXHIBITION PROVIDES NEW INSIGHT INTO THE GLOBALIZATION OF CONCEPTUAL ART, THROUGH WORK OF NEARLY 50 MOSCOW-BASED ARTISTS THINKING PICTURES FEATURES APPROXIMATELY 80 WORKS, INCLUDING MAJOR INSTALLATIONS, WORKS ON PAPER, PAINTINGS, MIXED-MEDIA WORKS, AND DOCUMENTARY MATERIALS, MANY OF WHICH OF HAVE NOT BEEN PUBLICLY DISPLAYED IN THE U.S. New Brunswick, NJ—February 23, 2016—Through the work of nearly 50 artists, the upcoming exhibition Thinking Pictures will introduce audiences to the development and evolution of conceptual art in Moscow—challenging notions of the movement as solely a reflection of its Western namesake. Opening at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers in September 2016, the exhibition will explore the unique social, political, and artistic conditions that inspired and distinguished the work of Muscovite artists from peers working in the U.S. and Western Europe. Under constant threat of censorship, and frequently engaging in critical opposition to Soviet-mandated Socialist Realism, these artists created works that defied classification, interweaving painting and installation, parody and performance, and images and texts in new types of conceptual art practices. Drawn from the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection at the Zimmerli, the exhibition features masterworks by such renowned artists as Ilya Kabakov, Komar and Melamid, Eric Bulatov, Andrei Monastyrsky, and Irina Nakhova, and introduces important works by under-represented artists, including Yuri Albert, Nikita Alekseev, Ivan Chuikov, Elena Elagina, Igor Makarevich, Viktor Pivovarov, Oleg Vassiliev, and Vadim Zakharov. Many of the works in the exhibition have never been publicly shown in the U.S., and many others only in limited engagement. Together, these works, created in a wide-range of media, underscore the diversity and richness of the underground artistic currents that comprise ‘Moscow Conceptualism’, and provide a deeper and more global understanding of conceptual art, and its relationship to world events and circumstances. -

Detki V Kletke: the Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry

Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Morse, Ainsley. 2016. Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493521 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry A dissertation presented by Ainsley Elizabeth Morse to The Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Slavic Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Ainsley Elizabeth Morse. All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Stephanie Sandler Ainsley Elizabeth Morse Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry Abstract Since its inception in 1918, Soviet children’s literature was acclaimed as innovative and exciting, often in contrast to other official Soviet literary production. Indeed, avant-garde artists worked in this genre for the entire Soviet period, although they had fallen out of official favor by the 1930s. This dissertation explores the relationship between the childlike aesthetic as expressed in Soviet children’s literature, the early Russian avant-garde and later post-war unofficial poetry. -

PUBLICATIONS Spring 2012 CORNERHOUSE PUBLICATIONS SPRING 2012 INDEX to FEATURED PUBLISHERS

PUBLICATIONS Spring 2012 CORNERHOUSE PUBLICATIONS SPRING 2012 INDEX TO FEATURED PUBLISHERS Welcome to our new catalogue featuring 156 titles from many of the most innovative Arnolfini 1 galleries, museums and publishers working in contemporary visual arts. We are Art Editions North 1 particularly pleased to have been appointed distributor for Blain|Southern, Lisson Gallery, Blain|Southern 1 Parasol unit, and Tatton Park Biennial, and new titles from these publishers are featured. Cornerhouse 2 Our list encompasses all the visual arts including architecture, art theory and education, Drawing Room 3 design, digital media, fashion, film and video, painting, photography, performance and DuMont Buchverlag 3 sculpture. We have over 2,700 titles currently available. If you require further details or if Ffotogallery 4 you want to order any of these titles, please contact us or visit our online bookstore. Firstsite 5 GlobalArtAffairs Publishing 5 For further information about our services, please contact Paul Daniels, Publications Haunch of Venison 5 Director. Hayward Publishing 7 Cornerhouse Publications Information as Material 9 JRP|Ringier* 10 70 Oxford Street, Manchester M1 5NH, England Kerber Verlag** 19 Publications Director Paul Daniels Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König 25 Lisson Gallery 39 Arnolfini Art Editions North Blain|Southern orders / customer services contact Debbie Fielding, James Brady or Suzanne Davies distributed by Cornerhouse world-wide distributed by Cornerhouse world-wide distributed by Cornerhouse world-wide trade orders -

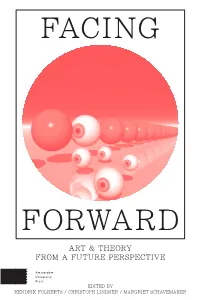

FACING FORWARD Art & Theory from a Future Perspective

This spirited exploration of the interfaces between art and theory in the 21st century brings together a range F of viewpoints on their future. Drawn from across the A fields of art history, architecture, philosophy, and media C FACING studies, the authors examine contemporary visual culture based on speculative predictions and creative scientific I arguments. Focusing on seven themes — N Future Tech G Future Image Future Museum Future City Future Freedom Future History & Future Future — the book shows how our sense of the future is shaped by a pervasive visual rhetoric of acceleration, progression, excess, and destruction. Contributors include: Hans Belting Manuel Delando Amelia Jones Rem Koolhaas China Miéville Hito Steyerl David Summers F O R W FORWARD A R ART & THEORY D FROM A FUTURE PERSPECTIVE AUP.nl 9789089647993 EDITED BY HENDRIK FOLKERTS / CHRISTOPH LINDNER / MARGRIET SCHAVEMAKER FACING FORWARD Art & Theory from a Future Perspective Edited by Hendrik Folkerts / Christoph Lindner / Margriet Schavemaker AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS COLOPHON This book is published in print and online Amsterdam University Press English- through the online OAPEN library (www. language titles are distributed in the US oapen.org). OAPEN (Open Access Publish- and Canada by the University of Chicago ing in European Networks) is a collabora- Press. tive initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic resAearch by aggre- gating peer reviewed Open Access publica- tions from across Europe. PARTNERS ISBN Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam 978 90 8964 799 3 University of Amsterdam E-ISBN Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam 978 90 4852 623 9 (SMBA) NUR De Appel arts centre 670 W139 Metropolis M COVER DESIGN AND LAYOUT Studio Felix Salut and Stefano Faoro Creative Commons License CC BY NC (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam, 2015 Some rights reserved. -

The International Criminal Tribunal

MICT-13-55-A 2970 A2970-A2901 15 March 2017 AJ THE MECHANISM FOR INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNALS No. MICT-13-55-A IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Judge Theodor Meron Judge William Hussein Sekule Judge Vagn Prusse Joensen Judge Jose Ricardo de Prada Solaesa Judge Graciela Susana Gatti Santana Registrar: Mr Olufemi Elias Date Filed: 15 March 2017 THE PROSECUTOR v. RADOVAN KARADZIC Public Redacted Version RADOVAN KARADZIC’S RESPONSE BRIEF ________________________________________________________________________ Office of the Prosecutor: Laurel Baig Barbara Goy Katrina Gustafson Counsel for Radovan Karadzic Peter Robinson Kate Gibson No. MICT-13-55-A 2969 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 4 II. THE PROSECUTION’S APPEAL .................................................................................. 5 1. The Excluded Crimes were Rightly Excluded .............................................................. 5 A. The Trial Chamber committed no legal error in identifying another reasonable inference ...................................................................................................... 7 B. The finding that the Excluded Crimes did not form part of the JCE was reasonable .................................................................................................................... 10 1. The Trial Chamber never found that President Karadzic knew the Excluded Crimes were necessary to achieve the common criminal purpose.........