Download (1233Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worlds Apart: Bosnian Lessons for Global Security

Worlds Apart Swanee Hunt Worlds Apart Bosnian Lessons for GLoBaL security Duke university Press Durham anD LonDon 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. To my partners c harLes ansBacher: “Of course you can.” and VaLerie GiLLen: “Of course we can.” and Mirsad JaceVic: “Of course you must.” Contents Author’s Note xi Map of Yugoslavia xii Prologue xiii Acknowledgments xix Context xxi Part i: War Section 1: Officialdom 3 1. insiDe: “Esteemed Mr. Carrington” 3 2. outsiDe: A Convenient Euphemism 4 3. insiDe: Angels and Animals 8 4. outsiDe: Carter and Conscience 10 5. insiDe: “If I Left, Everyone Would Flee” 12 6. outsiDe: None of Our Business 15 7. insiDe: Silajdžić 17 8. outsiDe: Unintended Consequences 18 9. insiDe: The Bread Factory 19 10. outsiDe: Elegant Tables 21 Section 2: Victims or Agents? 24 11. insiDe: The Unspeakable 24 12. outsiDe: The Politics of Rape 26 13. insiDe: An Unlikely Soldier 28 14. outsiDe: Happy Fourth of July 30 15. insiDe: Women on the Side 33 16. outsiDe: Contact Sport 35 Section 3: Deadly Stereotypes 37 17. insiDe: An Artificial War 37 18. outsiDe: Clashes 38 19. insiDe: Crossing the Fault Line 39 20. outsiDe: “The Truth about Goražde” 41 21. insiDe: Loyal 43 22. outsiDe: Pentagon Sympathies 46 23. insiDe: Family Friends 48 24. outsiDe: Extremists 50 Section 4: Fissures and Connections 55 25. -

Nisad 'Šiško' Jakupović

Nisad ‘Šiško’ Jakupović Nisad is from Prijedor in Bosnia. He was imprisoned in the notorious Omarska Concentration Camp with four of his brothers in 1992. ‘I was under arrest at a local school sports pitch, and there was a guard – a former desk mate from school and close neighbour – who ignored me when I clearly needed help. Yet there was a similar situation where another familiar face, someone I knew less well, chose to help me out.’ Nisad was born on 30 April 1965 in Prijedor, a town and region in the north-west of Bosnia, (then part of Yugoslavia). A year later Nisad’s parents decided to move him and his 10 brothers and sisters to a village called Kevljani, a few kilometres from the town of Prijedor. His father worked on the railway, along with three of his brothers, whilst his mother stayed at home. Nisad and his siblings were pupils at the secondary school in Omarska. Growing up, Nisad remembers Kevljani as a diverse community of Bosnian Muslims (known as Bosniaks) and Serbs. Nisad and his family were Bosnian Muslims, and he remembers everyone lived alongside each other with little conflict or tension. Nisad studied geology for four years, but after being unsuccessful in finding a job, as was the case with many young people at the time, he moved to Croatia to work as a labourer. Nisad regularly returned home to his family in Kevljani, but in the 1990s, there was a civil conflict and war in the region, and Yugoslavia began to be broken up into separate countries. -

Bosnia-Herzegovina - How Much Did Islam Matter ? Xavier Bougarel

Bosnia-Herzegovina - How Much Did Islam Matter ? Xavier Bougarel To cite this version: Xavier Bougarel. Bosnia-Herzegovina - How Much Did Islam Matter ?. Journal of Modern European History, Munich : C.H. Beck, London : SAGE 2018, XVI, pp.164 - 168. 10.17104/1611-8944-2018-2- 164. halshs-02546552 HAL Id: halshs-02546552 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02546552 Submitted on 18 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 « Bosnia-Herzegovina – How Much Did Islam Matter ? », Journal of Modern European History, vol. XVI, n° 2, 2018, pp.164-168. Xavier Bougarel The Bosniaks, both victims and actors in the Yugoslav crisis Referred to as ‘Muslims’ (in the national meaning of the term) until 1993, the Bosniaks were the main victims of the breakup of Yugoslavia. During the war that raged in Bosnia- Herzegovina from April 1992 until December 1995, 97,000 people were killed: 65.9% of them were Bosniaks, 25.6% Serbs and 8.0% Croats. Of the 40,000 civilian victims, 83.3% were Bosniaks. Moreover, the Bosniaks represented the majority of the 2.1 million people displaced by wartime combat and by the ‘ethnic cleansing’ perpetrated by the ‘Republika Srpska’ (‘Serb Republic’) and, on a smaller scale, the ‘Croat Republic of Herceg-Bosna’. -

The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory

The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory Elmedin Žunić ORCID ID: 0000-0003-3694-7098 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Melbourne Faculty of Fine Arts and Music July 2018 Abstract The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory concerns the representation of historic and traumatogenic events in art through the specific case of the war in Bosnia 1992-1995. The research investigates an aftermath articulated through the Freudian concept of Nachträglichkeit, rebounding on the nature of representation in the art as always in the space of an "afterness". The ability to represent an originary traumatic scenario has been questioned in the theoretics surrounding this concept. Through The Bosnian Case and its art historical precedents, the research challenges this line of thinking, identifying, including through fieldwork in Bosnia in 2016, the continuation of the war in a war of images. iii Declaration This is to certify that: This dissertation comprises only my original work towards the PhD except where indicated. Due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used. This dissertation is approximately 40,000 words in length, exclusive of figures, references and appendices. Signature: Elmedin Žunić, July 2018 iv Acknowledgements First and foremost, my sincere thanks to my supervisors Dr Bernhard Sachs and Ms Lou Hubbard. I thank them for their guidance and immense patience over the past four years. I also extend my sincere gratitude to Professor Barbara Bolt for her insightful comments and trust. I thank my fellow candidates and staff at VCA for stimulating discussions and support. -

NUSRETA SIVAC's VOICE

VOICES Check against delivery 24 April 2009 NUSRETA SIVAC’s VOICE “My name is Nusreta Sivac and I come from Prijedor, a city in northwest part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Before I share my very difficult experience in the concentration camp in Omarska, I would like to say that I am very happy to see that the tradition of Voices continues. I am also pleased to see some of the participants at the Voices from South Africa in 2001. For me it is very important that we have been given another opportunity to speak and that our voices are heard again. In April 1992 the Bosnian Serbs took forcibly power in Prijedor, that with the help of police, the former Yugoslav army (who at that time was composed of only Serbs) and the paramilitary forces from Serbia. In Prijedor the majority population was of Bosnian Bosniaks (Muslims), then Serbs (Ortodox Christians), Croats (Catholics) and other minority communities. Soon after Serbs took power, the areas populated by Muslims and Croats were started to be granated, houses were plundered, burned and then completely destroyed. ‘Ciscenje’ or ‘Cleaning’ was the terminology Serbs used for ethnic cleansing of Muslims and Croats. All the Muslim and Croat population in those areas was taken to the existing concentration camps. Later on men and women were divided, men would remain in the concentration camps and majority of women and children were later gathered in tracks and taken close to the borders of the Federation from where they sought protection of the Bosnian army. In the city of Prijedor at that time, freedom of movement was strictly limited. -

The International Criminal Tribunal

MICT-13-55-A 2970 A2970-A2901 15 March 2017 AJ THE MECHANISM FOR INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNALS No. MICT-13-55-A IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Judge Theodor Meron Judge William Hussein Sekule Judge Vagn Prusse Joensen Judge Jose Ricardo de Prada Solaesa Judge Graciela Susana Gatti Santana Registrar: Mr Olufemi Elias Date Filed: 15 March 2017 THE PROSECUTOR v. RADOVAN KARADZIC Public Redacted Version RADOVAN KARADZIC’S RESPONSE BRIEF ________________________________________________________________________ Office of the Prosecutor: Laurel Baig Barbara Goy Katrina Gustafson Counsel for Radovan Karadzic Peter Robinson Kate Gibson No. MICT-13-55-A 2969 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 4 II. THE PROSECUTION’S APPEAL .................................................................................. 5 1. The Excluded Crimes were Rightly Excluded .............................................................. 5 A. The Trial Chamber committed no legal error in identifying another reasonable inference ...................................................................................................... 7 B. The finding that the Excluded Crimes did not form part of the JCE was reasonable .................................................................................................................... 10 1. The Trial Chamber never found that President Karadzic knew the Excluded Crimes were necessary to achieve the common criminal purpose......... -

A Memorial in Exile in London's Olympics: Orbits of Responsibility

A memorial in exile in London’s Olympics: orbits of responsibility opendemocracy.net /susan-schuppli/memorial-in-exile-in-london%E2%80%99s-olympics-orbits-of- responsibility Susan Schuppli Two sets of extraordinary statistics attached to contemporary events are not connected to each other in a relationship of cause and effect but through a chain of associations and a series of responsibilities not faced and thus acted upon. In 2005 ArcelorMittal made a commitment to finance and build a memorial on the grounds of Omarska, the site of the most notorious concentration camp of the Bosnian war. Twenty years after the war crimes committed there, still no space of public commemoration exists. Grounds, buildings, and equipment once used for extermination now serve a commercial enterprise run by the world’s largest steel producer. In the absence of this promised memorial, London’s Olympic landmark - the ArcelorMittal Orbit - must be reclaimed as The Omarska Memorial in Exile. ArcelorMittal Orbit (designed by Anish Kapoor/ Cecil Balmond). Image courtesy of ArcelorMittal. All rights reserved. Access denied The story that links London to Omarska forcefully came to my attention when a group of us from Goldsmiths University of London, the Belgrade/Prijedor/Graz- based collective working group on the ‘Four Faces of Omarska’ along with survivors of the persecutions of the Bosnian war drove around the perimeter of the Omarska mining complex on April 13. Were it not for the survivors’ moving personal accounts and commitment to helping us comprehend the tragic events, we might well have succumbed to a form of dark tourism as our bus moved through a landscape still drained of colour after the winter. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Country Handbook 1

Bosnia and Herzegovina Country Handbook 1. This handbook provides basic reference information on Bosnia and Herzegovina, including its geography, history, government, military forces, and communications and transportation networks. This information is intended to familiarize military personnel with local customs and area knowledge to assist them during their assignment to Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2. This product is published under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Intelligence Production Program (DoDIPP) with the Marine Corps Intelligence Activity designated as the community coordinator for the Country Handbook Program. This product reflects the coordinated U.S. Defense Intelligence Community position on Bosnia and Herzegovina. 3. Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, NATO member countries, and other countries as required and designated for support of coalition operations. 4. The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for research, comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated personnel in their official duties, including local reproduction for training. Further dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this document, to include excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code. Contents KEY FACTS. 1 U.S. MISSION . 2 U.S. Embassy. 2 U.S. Consulate . 2 Entry Requirements . 3 Currency . 3 Customs . 3 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE . 4 Geography . 4 Topography . 5 Vegetation . 8 Effects on Military Operations . 9 Climate. 10 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATION . 13 Transportation . 13 Roads . 13 Rail . 15 Air . 16 Maritime . 17 Communication . 18 Radio and Television . 18 Telephone and Telegraph . -

Remembering Wartime Rape in Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina

Remembering Wartime Rape in Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarah Quillinan ORCHID ID: 0000-0002-5786-9829 A dissertation submitted in total fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2019 School of Social and Political Sciences University of Melbourne THIS DISSERTATION IS DEDICATED TO THE WOMEN SURVIVORS OF WAR RAPE IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA WHOSE STRENGTH, FORTITUDE, AND SPIRIT ARE TRULY HUMBLING. i Contents Dedication / i Declaration / iv Acknowledgments / v Abstract / vii Note on Language and Pronunciation / viii Abbreviations / ix List of Illustrations / xi I PROLOGUE Unclaimed History: Memoro-Politics and Survivor Silence in Places of Trauma / 1 II INTRODUCTION After Silence: War Rape, Trauma, and the Aesthetics of Social Remembrance / 10 Where Memory and Politics Meet: Remembering Rape in Post-War Bosnia / 11 Situating the Study: Fieldwork Locations / 22 Bosnia and Herzegovina: An Ethnographic Sketch / 22 The Village of Selo: Republika Srpska / 26 The Town of Gradić: Republika Srpska / 28 Silence and the Making of Ethnography: Methodological Framework / 30 Ethical Considerations: Principles and Practices of Research on Rape Trauma / 36 Organisation of Dissertation / 41 III CHAPTER I The Social Inheritance of War Trauma: Collective Memory, Gender, and War Rape / 45 On Collective Memory and Social Identity / 46 On Collective Memory and Gender / 53 On Collective Memory and the History of Wartime Rape / 58 Conclusion: The Living Legacy of Collective Memory in Bosnia and Herzegovina / 64 ii IV CHAPTER II The Unmaking -

Lesson Plan 1 Lesson 1 of 3 – a Personal Experience of the Bosnian War

The Forgiveness Project Forgiving the Unforgivable – Lesson Plan 1 Lesson 1 of 3 – A personal experience of the Bosnian War Kemal Pervanic’s story – Part 1 55 mins (film duration 9 mins) © 2017 The Forgiveness Project | www.theforgivenessproject.com A personal experience of the Bosnian War Please ensure the staff member facilitating this lesson has an understanding of the Bosnian War. A timeline is at the end of this lesson plan. This short clip (7 mins) from the 1995 BBC documentary, Death of Yugoslavia, sets out the process and scale of ethnic cleansing during the Bosnian War: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VbNocQORWQ8. Please note this contains very graphic scenes and is not suitable to be shown to the students. Lesson objective: 1. To be able to explain the personal experience of someone who has lived through the Bosnian War. Key vocabulary: Yugoslavia, nationalism, persecuted, concentration camp, Omarska camp, Prijedor massacre, demonise. Teacher activity Learner activity Time Who is Kemal Pervanic / Profile of Kemal Read the passage in the 5 mins Invite students to read the passage in their student booklet in student booklet and pairs and to complete the profile of Kemal as a teenager. complete the profile. Kemal Pervanic’s story / Film notes Watch the film and make 20 mins Introduce the story and the ground rules. Watch the film and notes or write questions ask students to make notes or questions throughout the film of throughout the film of any any words they don’t fully understand or parts of the story they words you don’t fully would like to discuss afterwards. -

Case Information Sheet

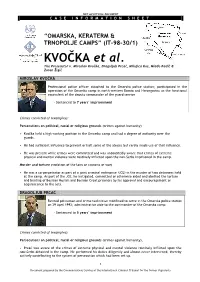

NOT AN OFFICIAL DOCUMENT CASE INFORMATION SHEET “OMARSKA, KERATERM & TRNOPOLJE CAMPS” (IT-98-30/1) KVOĈKA et al. The Prosecutor v. Miroslav Kvočka, Dragoljub Prcać, Milojica Kos, Mlađo Radić & Zoran Žigić MIROSLAV KVOĈKA Professional police officer attached to the Omarska police station; participated in the operation of the Omarska camp in north-western Bosnia and Herzegovina as the functional equivalent of the deputy commander of the guard service - Sentenced to 7 years’ imprisonment Crimes convicted of (examples): Persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds (crimes against humanity) • Kvoĉka held a high-ranking position in the Omarska camp and had a degree of authority over the guards. • He had sufficient influence to prevent or halt some of the abuses but rarely made use of that influence. • He was present while crimes were committed and was undoubtedly aware that crimes of extreme physical and mental violence were routinely inflicted upon the non-Serbs imprisoned in the camp. Murder and torture (violation of the laws or customs of war) • He was a co-perpetrator as part of a joint criminal enterprise (JCE) in the murder of two detainees held at the camp. As part of the JCE, he instigated, committed or otherwise aided and abetted the torture and beating of Bosnian Muslim and Bosnian Croat prisoners by his approval and encouragement or acquiescence to the acts. DRAGOLJUB PRCAĆ Retired policeman and crime technician mobilised to serve in the Omarska police station on 29 April 1992; administrative aide to the commander of the Omarska camp - Sentenced to 5 years’ imprisonment Crimes convicted of (examples): Persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds (crimes against humanity), • Prcać was aware of the crimes of extreme physical and mental violence routinely inflicted upon the non-Serbs detained in the camp. -

United Nations

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No.: IT-95-8-S Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 13 November 2001 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Original: ENGLISH Former Yugoslavia since 1991 IN THE TRIAL CHAMBER Before: Judge Patrick Robinson, Presiding Judge Richard May Judge Mohamed Fassi Fihri Registrar: Mr. Hans Holthuis Judgement of: 13 November 2001 PROSECUTOR v. DU[KO SIKIRICA DAMIR DO[EN DRAGAN KOLUNDŽIJA __________________________________________________________ SENTENCING JUDGEMENT ____________________________________________________________ The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Dirk Ryneveld Ms. Julia Baly Mr. Daryl Mundis Counsel for the Accused: Mr. Veselin Londrovi} and Mr. Michael Greaves, for Du{ko Sikirica Mr. Vladimir Petrovi} and Mr. Goran Rodi}, for Damir Do{en Mr. Ivan Lawrence and Mr. Jovan Ostoji}, for Dragan Kolundžija Case No. IT-95-8-S 13 November 2001 I. INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................. 1 A. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 B. THE PLEA AGREEMENTS ................................................................................................. 5 1. The Sikirica Plea Agreement........................................................................................ 5 2. The Do{en Plea Agreement .......................................................................................... 7 3. The Kolund`ija