A Memorial in Exile in London's Olympics: Orbits of Responsibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worlds Apart: Bosnian Lessons for Global Security

Worlds Apart Swanee Hunt Worlds Apart Bosnian Lessons for GLoBaL security Duke university Press Durham anD LonDon 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. To my partners c harLes ansBacher: “Of course you can.” and VaLerie GiLLen: “Of course we can.” and Mirsad JaceVic: “Of course you must.” Contents Author’s Note xi Map of Yugoslavia xii Prologue xiii Acknowledgments xix Context xxi Part i: War Section 1: Officialdom 3 1. insiDe: “Esteemed Mr. Carrington” 3 2. outsiDe: A Convenient Euphemism 4 3. insiDe: Angels and Animals 8 4. outsiDe: Carter and Conscience 10 5. insiDe: “If I Left, Everyone Would Flee” 12 6. outsiDe: None of Our Business 15 7. insiDe: Silajdžić 17 8. outsiDe: Unintended Consequences 18 9. insiDe: The Bread Factory 19 10. outsiDe: Elegant Tables 21 Section 2: Victims or Agents? 24 11. insiDe: The Unspeakable 24 12. outsiDe: The Politics of Rape 26 13. insiDe: An Unlikely Soldier 28 14. outsiDe: Happy Fourth of July 30 15. insiDe: Women on the Side 33 16. outsiDe: Contact Sport 35 Section 3: Deadly Stereotypes 37 17. insiDe: An Artificial War 37 18. outsiDe: Clashes 38 19. insiDe: Crossing the Fault Line 39 20. outsiDe: “The Truth about Goražde” 41 21. insiDe: Loyal 43 22. outsiDe: Pentagon Sympathies 46 23. insiDe: Family Friends 48 24. outsiDe: Extremists 50 Section 4: Fissures and Connections 55 25. -

Nisad 'Šiško' Jakupović

Nisad ‘Šiško’ Jakupović Nisad is from Prijedor in Bosnia. He was imprisoned in the notorious Omarska Concentration Camp with four of his brothers in 1992. ‘I was under arrest at a local school sports pitch, and there was a guard – a former desk mate from school and close neighbour – who ignored me when I clearly needed help. Yet there was a similar situation where another familiar face, someone I knew less well, chose to help me out.’ Nisad was born on 30 April 1965 in Prijedor, a town and region in the north-west of Bosnia, (then part of Yugoslavia). A year later Nisad’s parents decided to move him and his 10 brothers and sisters to a village called Kevljani, a few kilometres from the town of Prijedor. His father worked on the railway, along with three of his brothers, whilst his mother stayed at home. Nisad and his siblings were pupils at the secondary school in Omarska. Growing up, Nisad remembers Kevljani as a diverse community of Bosnian Muslims (known as Bosniaks) and Serbs. Nisad and his family were Bosnian Muslims, and he remembers everyone lived alongside each other with little conflict or tension. Nisad studied geology for four years, but after being unsuccessful in finding a job, as was the case with many young people at the time, he moved to Croatia to work as a labourer. Nisad regularly returned home to his family in Kevljani, but in the 1990s, there was a civil conflict and war in the region, and Yugoslavia began to be broken up into separate countries. -

Bosnia-Herzegovina - How Much Did Islam Matter ? Xavier Bougarel

Bosnia-Herzegovina - How Much Did Islam Matter ? Xavier Bougarel To cite this version: Xavier Bougarel. Bosnia-Herzegovina - How Much Did Islam Matter ?. Journal of Modern European History, Munich : C.H. Beck, London : SAGE 2018, XVI, pp.164 - 168. 10.17104/1611-8944-2018-2- 164. halshs-02546552 HAL Id: halshs-02546552 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02546552 Submitted on 18 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 « Bosnia-Herzegovina – How Much Did Islam Matter ? », Journal of Modern European History, vol. XVI, n° 2, 2018, pp.164-168. Xavier Bougarel The Bosniaks, both victims and actors in the Yugoslav crisis Referred to as ‘Muslims’ (in the national meaning of the term) until 1993, the Bosniaks were the main victims of the breakup of Yugoslavia. During the war that raged in Bosnia- Herzegovina from April 1992 until December 1995, 97,000 people were killed: 65.9% of them were Bosniaks, 25.6% Serbs and 8.0% Croats. Of the 40,000 civilian victims, 83.3% were Bosniaks. Moreover, the Bosniaks represented the majority of the 2.1 million people displaced by wartime combat and by the ‘ethnic cleansing’ perpetrated by the ‘Republika Srpska’ (‘Serb Republic’) and, on a smaller scale, the ‘Croat Republic of Herceg-Bosna’. -

Download (1233Kb)

Original citation: Koinova, Maria and Karabegovic, Dzeneta . (2016) Diasporas and transitional justice : transnational activism from local to global levels of engagement. Global Networks (Oxford): a journal of transnational affairs . Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/83210 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: "This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Koinova, Maria and Karabegovic, Dzeneta . (2016) Diasporas and transitional justice : transnational activism from local to global levels of engagement. Global Networks (Oxford): a journal of transnational affairs ., which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/glob.12128 This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving." A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. -

NUSRETA SIVAC's VOICE

VOICES Check against delivery 24 April 2009 NUSRETA SIVAC’s VOICE “My name is Nusreta Sivac and I come from Prijedor, a city in northwest part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Before I share my very difficult experience in the concentration camp in Omarska, I would like to say that I am very happy to see that the tradition of Voices continues. I am also pleased to see some of the participants at the Voices from South Africa in 2001. For me it is very important that we have been given another opportunity to speak and that our voices are heard again. In April 1992 the Bosnian Serbs took forcibly power in Prijedor, that with the help of police, the former Yugoslav army (who at that time was composed of only Serbs) and the paramilitary forces from Serbia. In Prijedor the majority population was of Bosnian Bosniaks (Muslims), then Serbs (Ortodox Christians), Croats (Catholics) and other minority communities. Soon after Serbs took power, the areas populated by Muslims and Croats were started to be granated, houses were plundered, burned and then completely destroyed. ‘Ciscenje’ or ‘Cleaning’ was the terminology Serbs used for ethnic cleansing of Muslims and Croats. All the Muslim and Croat population in those areas was taken to the existing concentration camps. Later on men and women were divided, men would remain in the concentration camps and majority of women and children were later gathered in tracks and taken close to the borders of the Federation from where they sought protection of the Bosnian army. In the city of Prijedor at that time, freedom of movement was strictly limited. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Country Handbook 1

Bosnia and Herzegovina Country Handbook 1. This handbook provides basic reference information on Bosnia and Herzegovina, including its geography, history, government, military forces, and communications and transportation networks. This information is intended to familiarize military personnel with local customs and area knowledge to assist them during their assignment to Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2. This product is published under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Intelligence Production Program (DoDIPP) with the Marine Corps Intelligence Activity designated as the community coordinator for the Country Handbook Program. This product reflects the coordinated U.S. Defense Intelligence Community position on Bosnia and Herzegovina. 3. Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, NATO member countries, and other countries as required and designated for support of coalition operations. 4. The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for research, comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated personnel in their official duties, including local reproduction for training. Further dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this document, to include excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code. Contents KEY FACTS. 1 U.S. MISSION . 2 U.S. Embassy. 2 U.S. Consulate . 2 Entry Requirements . 3 Currency . 3 Customs . 3 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE . 4 Geography . 4 Topography . 5 Vegetation . 8 Effects on Military Operations . 9 Climate. 10 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATION . 13 Transportation . 13 Roads . 13 Rail . 15 Air . 16 Maritime . 17 Communication . 18 Radio and Television . 18 Telephone and Telegraph . -

Remembering Wartime Rape in Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina

Remembering Wartime Rape in Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarah Quillinan ORCHID ID: 0000-0002-5786-9829 A dissertation submitted in total fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2019 School of Social and Political Sciences University of Melbourne THIS DISSERTATION IS DEDICATED TO THE WOMEN SURVIVORS OF WAR RAPE IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA WHOSE STRENGTH, FORTITUDE, AND SPIRIT ARE TRULY HUMBLING. i Contents Dedication / i Declaration / iv Acknowledgments / v Abstract / vii Note on Language and Pronunciation / viii Abbreviations / ix List of Illustrations / xi I PROLOGUE Unclaimed History: Memoro-Politics and Survivor Silence in Places of Trauma / 1 II INTRODUCTION After Silence: War Rape, Trauma, and the Aesthetics of Social Remembrance / 10 Where Memory and Politics Meet: Remembering Rape in Post-War Bosnia / 11 Situating the Study: Fieldwork Locations / 22 Bosnia and Herzegovina: An Ethnographic Sketch / 22 The Village of Selo: Republika Srpska / 26 The Town of Gradić: Republika Srpska / 28 Silence and the Making of Ethnography: Methodological Framework / 30 Ethical Considerations: Principles and Practices of Research on Rape Trauma / 36 Organisation of Dissertation / 41 III CHAPTER I The Social Inheritance of War Trauma: Collective Memory, Gender, and War Rape / 45 On Collective Memory and Social Identity / 46 On Collective Memory and Gender / 53 On Collective Memory and the History of Wartime Rape / 58 Conclusion: The Living Legacy of Collective Memory in Bosnia and Herzegovina / 64 ii IV CHAPTER II The Unmaking -

Lesson Plan 1 Lesson 1 of 3 – a Personal Experience of the Bosnian War

The Forgiveness Project Forgiving the Unforgivable – Lesson Plan 1 Lesson 1 of 3 – A personal experience of the Bosnian War Kemal Pervanic’s story – Part 1 55 mins (film duration 9 mins) © 2017 The Forgiveness Project | www.theforgivenessproject.com A personal experience of the Bosnian War Please ensure the staff member facilitating this lesson has an understanding of the Bosnian War. A timeline is at the end of this lesson plan. This short clip (7 mins) from the 1995 BBC documentary, Death of Yugoslavia, sets out the process and scale of ethnic cleansing during the Bosnian War: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VbNocQORWQ8. Please note this contains very graphic scenes and is not suitable to be shown to the students. Lesson objective: 1. To be able to explain the personal experience of someone who has lived through the Bosnian War. Key vocabulary: Yugoslavia, nationalism, persecuted, concentration camp, Omarska camp, Prijedor massacre, demonise. Teacher activity Learner activity Time Who is Kemal Pervanic / Profile of Kemal Read the passage in the 5 mins Invite students to read the passage in their student booklet in student booklet and pairs and to complete the profile of Kemal as a teenager. complete the profile. Kemal Pervanic’s story / Film notes Watch the film and make 20 mins Introduce the story and the ground rules. Watch the film and notes or write questions ask students to make notes or questions throughout the film of throughout the film of any any words they don’t fully understand or parts of the story they words you don’t fully would like to discuss afterwards. -

Case Information Sheet

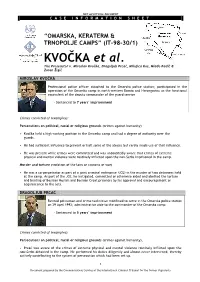

NOT AN OFFICIAL DOCUMENT CASE INFORMATION SHEET “OMARSKA, KERATERM & TRNOPOLJE CAMPS” (IT-98-30/1) KVOĈKA et al. The Prosecutor v. Miroslav Kvočka, Dragoljub Prcać, Milojica Kos, Mlađo Radić & Zoran Žigić MIROSLAV KVOĈKA Professional police officer attached to the Omarska police station; participated in the operation of the Omarska camp in north-western Bosnia and Herzegovina as the functional equivalent of the deputy commander of the guard service - Sentenced to 7 years’ imprisonment Crimes convicted of (examples): Persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds (crimes against humanity) • Kvoĉka held a high-ranking position in the Omarska camp and had a degree of authority over the guards. • He had sufficient influence to prevent or halt some of the abuses but rarely made use of that influence. • He was present while crimes were committed and was undoubtedly aware that crimes of extreme physical and mental violence were routinely inflicted upon the non-Serbs imprisoned in the camp. Murder and torture (violation of the laws or customs of war) • He was a co-perpetrator as part of a joint criminal enterprise (JCE) in the murder of two detainees held at the camp. As part of the JCE, he instigated, committed or otherwise aided and abetted the torture and beating of Bosnian Muslim and Bosnian Croat prisoners by his approval and encouragement or acquiescence to the acts. DRAGOLJUB PRCAĆ Retired policeman and crime technician mobilised to serve in the Omarska police station on 29 April 1992; administrative aide to the commander of the Omarska camp - Sentenced to 5 years’ imprisonment Crimes convicted of (examples): Persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds (crimes against humanity), • Prcać was aware of the crimes of extreme physical and mental violence routinely inflicted upon the non-Serbs detained in the camp. -

United Nations

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No.: IT-95-8-S Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 13 November 2001 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Original: ENGLISH Former Yugoslavia since 1991 IN THE TRIAL CHAMBER Before: Judge Patrick Robinson, Presiding Judge Richard May Judge Mohamed Fassi Fihri Registrar: Mr. Hans Holthuis Judgement of: 13 November 2001 PROSECUTOR v. DU[KO SIKIRICA DAMIR DO[EN DRAGAN KOLUNDŽIJA __________________________________________________________ SENTENCING JUDGEMENT ____________________________________________________________ The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Dirk Ryneveld Ms. Julia Baly Mr. Daryl Mundis Counsel for the Accused: Mr. Veselin Londrovi} and Mr. Michael Greaves, for Du{ko Sikirica Mr. Vladimir Petrovi} and Mr. Goran Rodi}, for Damir Do{en Mr. Ivan Lawrence and Mr. Jovan Ostoji}, for Dragan Kolundžija Case No. IT-95-8-S 13 November 2001 I. INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................. 1 A. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 B. THE PLEA AGREEMENTS ................................................................................................. 5 1. The Sikirica Plea Agreement........................................................................................ 5 2. The Do{en Plea Agreement .......................................................................................... 7 3. The Kolund`ija -

Tadic and Borovnica

THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA CASE NO. IT-94-1-I THE PROSECUTOR OF THE TRIBUNAL AGAINST DUSKO TADIC a/k/a "DULE" a/k/a "DUSAN" GORAN BOROVNICA INDICTMENT (AMENDED) Richard J. Goldstone, Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, pursuant to his authority under Article 18 of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia ("The Statute of the Tribunal") and Rule 50 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence of the Tribunal, charges: 1. Beginning on about 23 May 1992, Serb forces, supported by artillery and heavy weapons, attacked Bosnian Muslim and Croat population centres in opstina Prijedor, Bosnia-Herzegovina. In the following days, most of the Muslims and Croats were forced from their homes and seized by the Serb forces. The Serb forces then unlawfully confined thousands of Muslims and Croats in the Omarska, Keraterm and Trnopolje camps. The accused, Dusko TADIC a/k/a "Dule" a/k/a "Dusan", participated in the attack on, seizure, murder and maltreatment of Bosnian Muslims and Croats in opstina Prijedor both within the camps and outside the camps, between the period beginning about 23 May 1992 and ending about 31 December 1992. The accused, Goran BOROVNICA, participated with Dusko TADIC in the killing of Bosnian Muslims in the Kozarac area, as set forth below: BACKGROUND 2.1. About 23 May 1992, approximately three weeks after Serbs forcibly took control of governmental authority in opstina Prijedor, intensive shelling by Serb forces of Bosnian Muslim and Croat areas in opstina Prijedor caused Muslim and Croat residents to flee their homes. -

S/1994/674/Annex V Page 51 Cars in the Town Had "The Wolves Of

S/1994/674/Annex V Page 51 cars in the town had "The Wolves of Vukovar" written on them. In mid-May 1992, a number of Serbian trucks were observed in Kozarac. The head of a bull had been placed on the first truck. Attached to this truck was an inscription reading, "These are the Wolves of Vukovar" - the area of Vukovar in Croatia had by then been heavily ravaged. Locals interpreted this as intended to frighten them. As the weapons locally available were being collected by the Serbian army at the same time, the overall situation rendered the non-Serbian people with the feeling that they could do nothing. On occasion, Serbian aeroplanes were flying low over the roofs of private houses, scaring the dwellers and the local population at large even more. 245. The telephone lines were disconnected by the Serbs and so was the electricity supply. The area was surrounded by the Serbian army. No buses were in operation, and on 24 May 1992, the Serbs closed the main road traffic. Traffic between Prijedor and Banja Luka was then redirected via Tomašica and Omarska. On 24 May 1992, the air-raid alarm sounded. 246. Major Radmilo Zeljaja from the Krizni Štab Srpske Opštine Prijedor allegedly gave a delegation from the Kozarac civilian defence council an ultimatum either to sign a loyalty pledge to the Serbian self-appointed leaders (and hand over their weapons) or Kozarac would be attacked. The delegation asked for two days to consult with the population. The Serbian military attack followed. 247. Before the attack on the Kozarac area started on 24 May 1992, an announcement was made over Radio Prijedor that military forces with tanks were on their way from Banja Luka to Prijedor, and that if these were stopped, fire would be opened.