Recovering Creative Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

Record-World-1980-01

111.111110. SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS KOOL & THE GANG, "TOO HOT" (prod. by THE JAM, "THE ETON RIFLES" (prod. UTOPIA, "ADVENTURES IN UTO- Deodato) (writers: Brown -group) by Coppersmith -Heaven) (writer:PIA." Todd Rundgren's multi -media (Delightful/Gang, BMI) (3:48). Weller) (Front Wheel, BMI) (3:58). visions get the supreme workout on While thetitlecut fromtheir This brash British trio has alreadythis new album, originally written as "Ladies Night" LP hits top 5, topped the charts in their home-a video soundtrack. The four -man this second release from that 0land and they aim for the same unit combineselectronicexperi- album offers a midtempo pace success here with this tumultu- mentation with absolutely commer- with delightful keyboards & ousrocker fromthe"Setting cialrocksensibilities.Bearsville vocals. De-Lite 802 (Mercury). Sons" LP. Polydor 2051. BRK 6991 (WB) (7.98). CHUCK MANGIONE, "GIVE IT ALL YOU MIKE PINERA, "GOODNIGHT MY LOVE" THE BABYS, "UNION JACK." The GOT" (prod. by Mangione) (writ- (prod. by Pinera) (writer: Pinera) group has changed personnel over er: Mangione) (Gates, BMI) (3:55). (Bayard, BMI) (3:40). Pinera took the years but retained a dramatic From his upcoming "Fun And the Blues Image to #4 in'70 and thundering rock sound through- Games" LP is this melodic piece withhis "Ride Captain,Ride." out. Keyed by the single "Back On that will be used by ABC Sports He's hitbound again as a solo My Feet Again" this new album in the 1980 Winter Olympics. A actwiththistouchingballad should find fast AOR attention. John typically flawless Mangione work- that's as simple as it is effective. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Jukebox Titles Index 2017 - 2018

Jukebox Titles Index 2017 - 2018 Valid from 20th July 2018 www.jukebox-hire.co.uk [email protected] 07860 516 973 Looking for a Honeymoon / Holiday… Hawes Yorkshire Dales cottage? www.threehalfwayhouses.com 01 The 80s Part 2 … (CD Three) 03 Made in the 90s … CD – 1 01 Journey – Don’t Stop Believin’ 01. All Saints - Never Ever 02 Europe – The Final Countdown 02. En Vogue - Don't Let Go (Love) 03 Survivor – Eye Of The Tiger 03. Brandy & Monica - The Boy Is Mine 04 Alice Cooper – Poison 04. Jennifer Paige - Crush 05 Cher – If I Could Turn Back Time 05. Sixpence None The Richer - Kiss Me 06 The Stranglers – Golden Brown 06. Gabrielle - Dreams 07 The Specials – Ghost Town 07. Eternal Ft. Bebe Winans - I Wanna Be the Only One 08 Joy Division – Love Will Tear Us Apart 08. Salt - N 09 Psychedelic Furs – Pretty In Pink 09. Mark Morrison - Return Of The Mack 10 The Primitives – Crash 10. Jade - Don't Walk Away 11 Blondie – Call Me 11. Shanice - I Love Your Smile 12 Yazoo – Only You 12. Lenny Kravitz - It Ain't Over 'Til It's Over 13 Belle Stars – Sign of the Times 13. Lighthouse Family - High 14 Eighth Wonder – I’m Not Scared 14. Sweetbox - Everything's Gonna Be Alright 15 Westworld – Sonic Boom Boy 15. Shola Ama - You Might Need Somebody 16 A Flock Of Seagulls – Whishing Had Photo of You 16. Honeyz - Finally Found 17 Adam & Ants – Stand and Deliver 17. Donna Lewis - I Love You Always Forever 18 Big Audio Dynamite – E=MC2 18. -

Jukebox Titles Index Winter � 2015

Jukebox Titles Index Winter - 2015 th Valid from 7 December www.jukebox-hire.co.uk [email protected] 07860 516 973 Hint – to search for a particular song in this PDF file simply use ‘Ctrl’ and ‘F’ 01 I Grew Up in the 80’s – The No.1s 03 Made in the 90s CD – 1 01 Frankie Goes To Hollywood - Relax 01. All Saints - Never Ever 02 Black Box - Ride On Time 02. En Vogue - Don't Let Go (Love) 03 Yazz - The Only Way Is Up 03. Brandy & Monica - The Boy Is Mine 04 The Human League - Don't You Want Me 04. Jennifer Paige - Crush 05 Mel & Kim - Respectable 05. Sixpence None The Richer - Kiss Me 06 Dexy's Midnight Runners - Come On Eileen 06. Gabrielle - Dreams 07 The Jam - Town Called Malice 07. Eternal Ft. Bebe Winans - I Wanna Be the Only One 08 Duran Duran - The Reflex 08. Salt - N 09 Kajagoogoo - Too Shy 09. Mark Morrison - Return Of The Mack 10 Culture Club - Karma Chameleon 10. Jade - Don't Walk Away 11 Soul II Soul Ft Caron Wheeler - Back To Life 11. Shanice - I Love Your Smile 12 Blondie - The Tide Is High 12. Lenny Kravitz - It Ain't Over 'Til It's Over 13 UB40 - Red Red Wine 13. Lighthouse Family - High 14 The Specials - Ghost Town 14. Sweetbox - Everything's Gonna Be Alright 15 Foreigner - I Want To Know What Love Is 15. Shola Ama - You Might Need Somebody 16 Kylie Minogue & Jason Donovan - Especially For You 16. Honeyz - Finally Found 17 Spandau Ballet - True 17. -

Smash Hits Volume 24

November 1-14 1979 30p m> POLICE SPi im BATS LPs to be won Uover forbidden 1 *-.,. Records Mv" Rec . __.. ,«i»i Atlantic L^rs^ur^tohavevou onn !*»-»- »*' BY Chic at verv love you Chorus . er d MV no other *°^lr We'll just ?JJK» no o^er and everv *nev You're 'cause " do * « anc ' <e :«•want to your beckner- "VTn'tI - „ at I didn t tr oe And love" indeed That your ^neW ves to and the you are You «Y AppearanceapP That sinister a«W» Repeat chorus Those ur love dQ ^ forbidden .... ,o«e is : ooh " NlyK hidden g^— iV.WeeVo«r»ov. indeed yes chorus to Vou are a.neat D»ne at chorus U" Hello, I'm Page 3. I'm the page that gives the rundown on the rest of the issue, makes it all sound utterly fantastic and desirable, gets to crack a joke or Nov 1-14 1979 two, and generally acts all snappy and hot to trot. It's a piece of cake in this magazine, 'cause the other pages work so hard to come up with the goods — Vol 1 No 24 now my cousin, who's Page 3 of The Sun, he has a rotten time trying to dream up captions for pictures of nude ladies. (Get on with it — Ed.) OK OK, this time around Page 24 has asked me to tell you about his Quiz; Page 31 has Editorial address; Smash Hits, Lisa 52-55 asked me to remind you about his terrific badge offer — the complete set of House, Carnaby Street, London five W1V 1PF. -

The Ultimate Playlist This List Comprises More Than 3000 Songs (Song Titles), Which Have Been Released Between 1931 and 2018, Ei

The Ultimate Playlist This list comprises more than 3000 songs (song titles), which have been released between 1931 and 2021, either as a single or as a track of an album. However, one has to keep in mind that more than 300000 songs have been listed in music charts worldwide since the beginning of the 20th century [web: http://tsort.info/music/charts.htm]. Therefore, the present selection of songs is obviously solely a small and subjective cross-section of the most successful songs in the history of modern music. Band / Musician Song Title Released A Flock of Seagulls I ran 1982 Wishing 1983 Aaliyah Are you that somebody 1998 Back and forth 1994 More than a woman 2001 One in a million 1996 Rock the boat 2001 Try again 2000 ABBA Chiquitita 1979 Dancing queen 1976 Does your mother know? 1979 Eagle 1978 Fernando 1976 Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! 1979 Honey, honey 1974 Knowing me knowing you 1977 Lay all your love on me 1980 Mamma mia 1975 Money, money, money 1976 People need love 1973 Ring ring 1973 S.O.S. 1975 Super trouper 1980 Take a chance on me 1977 Thank you for the music 1983 The winner takes it all 1980 Voulez-Vous 1979 Waterloo 1974 ABC The look of love 1980 AC/DC Baby please don’t go 1975 Back in black 1980 Down payment blues 1978 Hells bells 1980 Highway to hell 1979 It’s a long way to the top 1975 Jail break 1976 Let me put my love into you 1980 Let there be rock 1977 Live wire 1975 Love hungry man 1979 Night prowler 1979 Ride on 1976 Rock’n roll damnation 1978 Author: Thomas Jüstel -1- Rock’n roll train 2008 Rock or bust 2014 Sin city 1978 Soul stripper 1974 Squealer 1976 T.N.T. -

The Jam Snap! Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Jam Snap! mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Snap! Country: Japan Released: 1983 Style: Mod MP3 version RAR size: 1736 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1239 mb WMA version RAR size: 1389 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 245 Other Formats: ASF MPC ADX AU MMF DTS AA Tracklist A1 In The City A2 Away From The Numbers A3 All Around The World A4 The Modern World A5 News Of The World A6 Billy Hunt A7 English Rose A8 Mr. Clean A9 David Watts A10 'A' Bomb In Wardour St A11 Down In The Tube Station At Midnight A12 Strange Town A13 The Butterfly Collector A14 When You're Young A15 Smithers-Jones B1 Thick As Thieves B2 The Eton Rifles B3 Going Underground B4 Dreams Of Children B5 That's Entertainment B6 Start! B7 Man In The Corner Shop B8 Funeral Pyre B9 Absolute Beginners B10 Tales From The Riverbank B11 Town Called Malice B12 Precious B13 The Bitterest Pill (I Ever Had To Swallow) B14 Beat Surrender Credits Cover [Designed By] – Simon Halfon Liner Notes – Paolo Hewitt Notes Double play cassette. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Snap! (2xLP, SNAP 1 The Jam Polydor SNAP 1 UK 1983 Comp) Snap! (2xLP, SNAP 1 The Jam Comp + 7", EP + Polydor SNAP 1 UK 1983 Ltd) SNAPC 1, 815 Snap! (Cass, Polydor, SNAPC 1, 815 The Jam Netherlands 1983 537-4 Comp) Polydor 537-4 422-815 537-1 Polydor, 422-815 537-1 Snap! (2xLP, Y-2, SNAP1, 815 The Jam Polydor, Y-2, SNAP1, 815 US Unknown Comp, MP, RE) 537-1 Y-2 Polydor 537-1 Y-2 Snap! (Cass, PDS4-2-6382 The Jam Polydor PDS4-2-6382 Canada 1983 Comp, Dol) Related Music albums to Snap! by The Jam 1. -

Polydor Records Discography 3000 Series

Polydor Records Discography 3000 series 25-3001 - Emergency! - The TONY WILLIAMS LIFETIME [1969] (2xLPs) Emergency/Beyond Games//Where/Vashkar//Via The Spectrum Road/Spectrum//Sangria For Three/Something Special 25-3002 - Back To The Roots - JOHN MAYALL [1971] (2xLPs) Prisons On The Road/My Children/Accidental Suicide/Groupie Girl/Blue Fox//Home Again/Television Eye/Marriage Madness/Looking At Tomorrow//Dream With Me/Full Speed Ahead/Mr. Censor Man/Force Of Nature/Boogie Albert//Goodbye December/Unanswered Questions/Devil’s Tricks/Travelling PD 2-3003 - Revolution Of The Mind-Live At The Apollo Volume III - JAMES BROWN [1971] (2xLPs) Bewildered/Escape-Ism/Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved/Get Up I Feel Like Being A Sex Machine/Give It Up Or Turnit A Loose/Hot Pants (She Got To Use What She Got To Need What She Wants)/I Can’t Stand It/I Got The Feelin’/It’s A New Day So Let A Man Come In And Do The Popcorn/Make It Funky/Mother Popcorn (You Got To Have A Mother For Me)/Soul Power/Super Bad/Try Me [*] PD 2-3004 - Get On The Good Foot - JAMES BROWN [1972] (2xLPs) Get On The Good Foot (Parts 1 & 2)/The Whole World Needs Liberation/Your Love Was Good For Me/Cold Sweat//Recitation (Hank Ballard)/I Got A Bag Of My Own/Nothing Beats A Try But A Fail/Lost Someone//Funky Side Of Town/Please, Please//Ain’t It A Groove/My Part-Make It Funky (Parts 3 & 4)/ Dirty Harri PD 2-3005 - Ten Years Are Gone - JOHN MAYALL [1973] (2xLPs) Ten Years Are Gone/Driving Till The Break Of Dawn/Drifting/Better Pass You By//California Campground/Undecided/Good Looking -

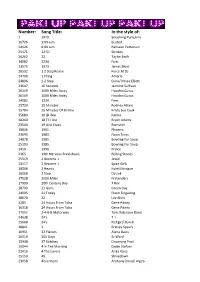

Song Title: in the Style Of: 1 1979

Number: Song Title: In the style of: 1 1979.. Smashing Pumpkins 16726 3:00 a.m. Busted 24126 6:00 a.m. Rahsaan Patterson 25171 12:51 Strokes 26262 22 Taylor Swift 14082 1234 Fiest 13575 1973 James Blunt 26532 1 2 Step Remix Force M Ds 24700 1 Thing Amerie 24896 1.2 Step Ciara/ Missy Elliott 23647 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan 26149 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus 26149 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus 14082 1234.. Fiest 25720 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 15784 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 15689 16 @ War Karina 18260 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 23540 19 And Crazy Bomshel 18846 1901.. Phoenix 23643 1983.. Neon Trees 24878 1985.. Bowling For Soup 25193 1985.. Bowling For Soup 1419 1999.. Prince 2165 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 25519 2 Become 1 Jewel 13117 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 18506 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 16068 2 Step Dj Unk 17028 2000 Miles Pretenders 17999 20th Century Boy T Rex 18730 21 Guns Green Day 24005 21 Today Piano Singalong 18670 22.. Lily Allen 3285 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 16318 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 17057 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 24638 24's T. I. 25660 24's Richgirl/ Bun B 18841 3.. Britney Spears 10951 32 Flavors Alana Davis 26519 365 Days Zz Ward 15938 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 15044 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 21410 4 The Lovers Arika Kane 25150 45.. Shinedown 23058 4evermore Anthony David/ Algeb 26356 4th Of July Brian McKnight 16144 5 Colours In Her Hair Mc Fly 1594 5.6.7.8 Steps 25883 50 Ways To Say Goodbye Train 16207 5-4-3-2-1 Manfred Mann 3809 57 Chevrolet Billie Jo Spears 18828 59th Street Bridge Song( No Harmony) Simon & Garfunkel 1694 59th Street Bridge Song( W Harmony) Simon & Garfunkel 16383 6345-789 Blues Brothers 11153 800 Pound Jesus Sawyer Brown 10385 80's Ladies K.t. -

Scanned Image

718"'"i Reggae Top 50 Reggae l2" Disco 45 s 1 MAKE IT VVITH YOU Carroll Thompson:,A inou Carousel 141b71 2 NICE & EASY Ruddy Thomas Hawkeye Bubbling 2FUSSIN' & FIGHTING/ ROCKING TIME Dennis A -Z guide to producers Brown Yvonne Spceial Singles 101-150 and publishers 4 BLOW MY MIND Arema City Boy Under 5 TU SHENG PENG U Brown Tads 6 GUN SHOT AnthenyJohnson Midnite Rock 7GIPSY LOVE (PART 1) Belinda Parker Sun Burst 8 BREAK YOUR PROMISE/UNMEETED TAXI 101 MAKE A CIRCUIT WITH ME POLECATS (MERCURY 1999 PRINCE (WARNER BROSI 24 A WINTER'S TALE MIKE BATT IAPRIUBATTSONGS/64 SOUARES/PENDU- Barn/ Biggs:Sly & Robbie Island POLE 4(121) LUMWARNER BROS) 77 9!SIT ALWAYS GONNA BE LIKE THIS Raymond: 102 HANGIN' CHIC ATLANTIC A9898(7)) AFRICA TOTO (APRIL] 9 Claudia) B Music 103 RIDE ON THE RHYTHM MAHOGANY (WEST END AIN'T NOBODY HERE BUT US CHICKENS PETER COLLINS (MCA) 91 10RUB A DUB SESSION Tnston Palma Intense ARIST 11215171 ALL AROUND THE WORLD SIC COPPERSMITH -HEAVEN (MORRISON 11 HEAVEN MUST HAVE SENTYOU (101 The LEAHY(AND SON) 67 Marvels Pama 104 LOVED ONE'S AN ANGEL BLUE ZOO (MAGNET ALL RIGHT MICHAEL OmAR-r.,, -F._ 45 12PLAY GIRL Techniques Techniques (12)MAC 240) ALL THE LOVE IN THE WORLD A P._ RICHARDSONiALBHY 13THEY NEVER KNOW JAH Wailing Souls 105 SHE WEARS MY RING P.ENATO (LIFESTYLE LIFE 2) GALUTEN IGIBB BROS 1.. -.Es s E._75 Greensleeves 106 HAVEN'T BEN FUNKED ENOUGH EXTRAS ITMT.) ATOMIC DOG GEORGE C.. 1 ss L',..SIZ) 90 14IF THIS WORLD WERE MINE Dennis Brown BABY, COME TO ME 0L,']," 41 Yvonne Special EXCELLENT TNT(T11) BE MINE TONIGHT/AND YOU -I'11140. -

15 Studio Sessions 15.1 Recording Information

15 Studio Sessions 15.1 Recording Information The table below shows Paul’s recording history. Several early songs were written but not recorded such as Little Girl Crying (Weller/Brookes), Remember (Weller/Brookes), Love Has Died (Weller/Brookes), Feels So Good (Weller/Brookes), That Way (Weller/Brookes), Love Love Loving (Weller/Brookes), Crazy Old World (Weller/Brookes), Like I Love You (Weller/Brookes), You And The Summer (Weller/Brookes), Say Goodbye (Weller/Brookes), She Don’t Need Me (Weller/Brookes), When I’m Near You (Weller/Brookes), Love’s Surprise (Weller/Brookes) & She’s Coming Home (Weller/Brookes). In his book “Shout To The Top”, Dennis Munday revealed that both Polydor and Paul’s tapes are held at The Eisenhower Centre, Tottenham Court Road, London. No. Song Title Group Written By Session Date Studio First Released On Released Date 1 Blueberry Rock The Jam Weller / Brookes August, 1973 Eden Studios, Kingston Not Released Unreleased 2 Takin’ My Love The Jam Weller / Brookes August, 1973 Eden Studios, Kingston Not Released Unreleased 3 Some Kinda Loving The Jam Weller / Brookes November, 1973 Fanfare Studios, Swiss Cottage, London Not Released Unreleased 4 Makin' My Way Back Home The Jam Weller / Brookes November, 1973 Fanfare Studios, Swiss Cottage, London Not Released Unreleased 5 Loving By Letters The Jam Weller / Brookes April 1974 Bob Potter’s Studio, Mytchett Not Released Unreleased 6 More And More The Jam Weller / Brookes April 1974 Bob Potter’s Studio, Mytchett Not Released Unreleased 7 Walking The Dog The Jam Weller