Everything's an Argument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Teens and a Budget It Pays to Belong !

Two Teens and a Budget It Paysays to Belong ! Two Teens and a Budget CHAPTER 1 - ANGELA Liam always insists that the car wasn’t the last straw. But trust me, it was. At least that’s what finally made dad explode at Uncle Billy’s house. And dad, like ... never explodes. Especially at Uncle Billy. Uncle Billy is that really rich, old, great uncle that everybody wishes they could have. And we actually have him. Lucky us, except of course, there’s a catch. Uncle Billy is totally useless. Not that he’s useless. He’s, like, super successful and filthy rich, and if you ask (or don’t ask), he’s more than happy to tell you all about his first job and his second job and his third job and his first business and his second business and … you get the picture. To hear Uncle Billy tell it, he was working while he was still in diapers. Whatever. Like anybody cares. Because he doesn’t do what rich, lonely uncles are supposed to do - such as adopt and lavish me with all the good things in life. Okay, maybe he’s not that lonely. He’s got Aunt Rose to keep him company and listen to how wonderful he is. And truthfully, I wouldn’t be all that good at that. But still. I’d listen if I thought it was worth my while. Which it’s totally not. As he likes to point out, the only valuables I’ll ever be getting from his will are jewels of advice. -

Life in Two City States--- Athens and Sparta

- . CHAPTER The city-states of Sparta (above) and Athens (below) were bitter rivals. Life in Two City-States Athens and Sparta 27.1 Introduction In Chapter 26, you learned that ancient Greece was a collection of city- states, each with its own government. In this chapter, you will learn about two of the most important Greek city-states, Athens and Sparta. They not only had different forms of government, but very different ways of life. Athens was a walled city near the sea. Nearby, ships came and went from a busy port. Inside the city walls, master potters and sculptors labored in work- shops. Wealthy people and their slaves strolled through the marketplace. Often the city's citizens (free men) gathered to loudly debate the issues of the day. Sparta was located in a farming area on a plain. No walls surrounded the city. Its buildings were simple and plain compared to those of Athens. Even the clothing of the people in the streets was drab. Columns of soldiers tramped through the streets, with fierce expressions behind their bronze helmets. Even a casual visitor could see that Athens and Sparta were very different. Let's take a closer look at the way people lived in these two city-states. We'll examine each city's government, economy, education, and treatment of women and slaves. Use this graphic organizer to help you compare various aspects of life in Athens and Sparta. Life in Two City-States: Athens and Sparta 259 27.2 Comparing Two City-States Peloponnesus the penin- Athens and Sparta were both Greek cities, and they were only sula forming the southern part about 150 miles apart. -

The Wild Robot.Pdf

Begin Reading Table of Contents Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. To the robots of the future CHAPTER 1 THE OCEAN Our story begins on the ocean, with wind and rain and thunder and lightning and waves. A hurricane roared and raged through the night. And in the middle of the chaos, a cargo ship was sinking down down down to the ocean floor. The ship left hundreds of crates floating on the surface. But as the hurricane thrashed and swirled and knocked them around, the crates also began sinking into the depths. One after another, they were swallowed up by the waves, until only five crates remained. By morning the hurricane was gone. There were no clouds, no ships, no land in sight. There was only calm water and clear skies and those five crates lazily bobbing along an ocean current. Days passed. And then a smudge of green appeared on the horizon. As the crates drifted closer, the soft green shapes slowly sharpened into the hard edges of a wild, rocky island. The first crate rode to shore on a tumbling, rumbling wave and then crashed against the rocks with such force that the whole thing burst apart. -

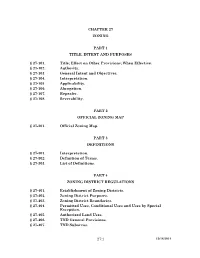

Chapter 27 Zoning Part 1 Title, Intent and Purposes

CHAPTER 27 ZONING PART 1 TITLE, INTENT AND PURPOSES § 27-101. Title; Effect on Other Provisions; When Effective. § 27-102. Authority. § 27-103. General Intent and Objectives. § 27-104. Interpretation. § 27-105. Applicability. § 27-106. Abrogation. § 27-107. Repealer. § 27-108. Severability. PART 2 OFFICIAL ZONING MAP § 27-201. Official Zoning Map. PART 3 DEFINITIONS § 27-301. Interpretation. § 27-302. Definition of Terms. § 27-303. List of Definitions. PART 4 ZONING DISTRICT REGULATIONS § 27-401. Establishment of Zoning Districts. § 27-402. Zoning District Purposes. § 27-403. Zoning District Boundaries. § 27-404. Permitted Uses, Conditional Uses and Uses by Special Exception. § 27-405. Authorized Land Uses. § 27-406. TND General Provisions. § 27-407. TND Subareas. 27:1 12/16/2014 § 27-408. TND Blocks, Streets and Parking. § 27-409. Dimensional Standards. § 27-410. Height Exceptions. § 27-411. Permitted Projections into Required Setbacks. § 27-412. Lot Access. § 27-413. Accessory Buildings, Structures, Uses and Events. § 27-414. Screening and Landscaping for Off-Street Parking and Service Structures for Nonresidential, Multifamily Dwelling/Apartments, Single-Family Attached and Mixed Uses. § 27-415. Vegetation Preservation and Buffer Yards. § 27-416. Cellar Structures. § 27-417. Fences and Walls. § 27-418. Graphic References. PART 5 SUPPLEMENTAL REGULATIONS § 27-501. Hazardous Substances. § 27-502. Fuel Pumps. § 27-503. Temporary Construction Trailers or Sheds. § 27-504. Outdoor Display and Storage. § 27-504.1. Community Gardens/Market Gardens. § 27-505. Solar Collectors and Solar-Related Equipment. § 27-506. Wind Energy Conversion Systems. § 27-507. Signage. § 27-508. Hours of Operation. § 27-509. Outdoor Storage. § 27-510. Delivery Plan. PART 6 USES BY SPECIAL EXCEPTION § 27-601. -

The Last Days of John Lennon

Copyright © 2020 by James Patterson Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 littlebrown.com twitter.com/littlebrown facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany First ebook edition: December 2020 Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. ISBN 978-0-316-42907-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945289 E3-111020-DA-ORI Table of Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 — Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 — Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 -

Texas Direct Farm Business Guide

TEXAS DIRECT FARM BUSINESS GUIDE MICHAELA TARR CHARLES CUNNINGHAM RUSTY W. RUMLEY 1 Texas Direct Farm Business Guide Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6 I. Using This Guide ............................................................................................................. 7 II. Overview of Administrative Agencies ......................................................................... 8 III. The Food and Drug Administration’s Food Code ...................................................... 10 IV. Texas State Department of Health .............................................................................. 10 Section 1: Farming Operations .................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 1: Structuring the Business .......................................................................................... 14 I. Planning the Direct Farm Business ................................................................................ 14 II. Choosing a Business Entity ........................................................................................ 16 III. Checklist ..................................................................................................................... 23 Chapter 2 - Setting up the Direct Farm Business:..................................................................... 24 I. Siting ............................................................................................................................. -

Refugee Boy Activity Pack.Pdf

Small Island Read 2007 Refugee Boy – Activity Pack Pack Contents Introduction 2 Personal Stories 13 Benjamin Zephaniah 3 The British 14 Refugee Boy: Summary 4 Coming to Britain 15 Refugee Boy: Questions for Discussion 6 Maps 16 Role Playing 7 The Transatlantic Slave Trade 18 Refugee Boy: Word-Search Quiz 8 The Slave Ship 20 We Refugees by Benjamin Zephaniah 9 The Empire Windrush 22 Ethiopia and Eritrea 10 Who are We? 24 Communities of Britain Word-Search 11 Resources 25 Asylum Seekers 12 Pupil Feedback Form 27 Small Island Read 2007 is a partnership initiative led by: It is funded by: Please photocopy as many of these sheets as you need for your group. Cover images courtesy of Bloomsbury. Pack written and compiled by Melanie Kelly. Designed by Qube Design Associates Ltd. Printed by Doveton Press. Answers to Word-Search Quiz: 1. Milford 2. Great Expectations 3. Spaghetti 4. Ireland 5. Mrs Kumar 6. Owen 7. Manor Park 8. Forest 9. Pithead 10. Leonie 11. Haile Selasse 12. Tabbas Noor 13. Euro Racer 14. Ethiopia 15. Gulf War 16. Asmara 17. Fernandez 18. Chile 19. Desta 20. East. Communities of Britain: the names hidden in the box are – Across: Scottish, Jute, Irish, English, Tamil, Celt, Indian, Iraqi, Roman, Saxon, Afghan; Down: Bangladeshi, Kurdish, Spanish, Vietnamese, Pict, Trinidadian, Jamaican, Japanese; Diagonal: Bosnian, Bajan. Small Island Read 2007 Refugee Boy – Activity Pack Introduction Small Island Read 2007 brings together Aye Write! the Glasgow book festival, the Great Reading Adventure (Bristol and the South West), Hull Libraries and Liverpool Reads to form the largest mass-reading project that has ever taken place in Britain. -

Where the Mountain Meets the Moon

Copyright © 2009 by Grace Lin All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Little, Brown Books for Young Readers Hachette Book Group 237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com Little, Brown Books for Young Readers is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. First eBook Edition: June 2009 The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. ISBN: 978-0-316-05260-3 Contents COPYRIGHT CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 3 CHAPTER 4 CHAPTER 5 CHAPTER 6 CHAPTER 7 CHAPTER 8 CHAPTER 9 CHAPTER 10 CHAPTER 11 CHAPTER 12 CHAPTER 13 CHAPTER 14 CHAPTER 15 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER 17 CHAPTER 18 CHAPTER 19 CHAPTER 20 CHAPTER 21 CHAPTER 22 CHAPTER 23 CHAPTER 24 CHAPTER 25 CHAPTER 26 CHAPTER 27 CHAPTER 28 CHAPTER 29 CHAPTER 30 CHAPTER 31 CHAPTER 32 CHAPTER 33 CHAPTER 34 CHAPTER 35 CHAPTER 36 CHAPTER 37 CHAPTER 38 CHAPTER 39 CHAPTER 40 CHAPTER 41 CHAPTER 42 CHAPTER 43 CHAPTER 44 CHAPTER 45 CHAPTER 46 CHAPTER 47 CHAPTER 48 AUTHOR’S NOTES FOR ROBERT SPECIAL THANKS TO: ALVINA, CONNIE, LIBBY, JANET, MOM, DAD, AND ALEX CHAPTER 1 Far away from here, following the Jade River, there was once a black mountain that cut into the sky like a jagged piece of rough metal. -

Sideways Stories from Wayside School

g g In memory of Robert J. Sachar and to my mother, Andy, and Jeff g g . Contents . Introduction Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Chapter 29 Chapter 30 About Louis Sachar Imprint g Introduction This book contains thirty stories about the children and teachers at Wayside School. But before we get to them, there is something you ought to know so that you don’t get confused. Wayside School was accidentally built sideways. It was supposed to be only one story high, with thirty classrooms all in a row. Instead it is thirty stories high, with one classroom on each story. The builder said he was very sorry. The children at Wayside like having a sideways school. They have an extra-large playground. The children and teachers described in this book all go to class on the top floor. So there are thirty stories from the thirtieth story of Wayside School. It has been said that these stories are strange and silly. That is probably true. However, when I told stories about you to the children at Wayside, they thought you were strange and silly. That is probably also true. g g Chapter 1 Mrs. Gorf Mrs. Gorf had a long tongue and pointed ears. She was the meanest teacher in Wayside School. -

Audio Plug-Ins Guide Legal Notices

Audio Plug-Ins Guide Legal Notices © 2021 Avid Technology, Inc., (“Avid”), all rights reserved. This guide may not be duplicated in whole or in part without the written consent of Avid. For a current and complete list of Avid trademarks visit: www.avid.com/legal/trademarks-and-other-notices. Bonjour, the Bonjour logo, and the Bonjour symbol are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. Thunderbolt and the Thunderbolt logo are trademarks of Intel Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. This product may be protected by one or more U.S. and non-U.S. patents. Details are available at www.avid.com/patents. Product features, specifications, system requirements, and availability are subject to change without notice. Guide Part Number 9329-66265-00 REV A 06/21 Contents Part I Introduction to Audio Plug-Ins Chapter 1. Audio Plug-Ins Overview. 1 Plug-In Formats . 1 Avid Audio Plug-Ins . 1 Using Plug-Ins in Pro Tools. 3 System Requirements and Compatibility for Plug-Ins . 3 Avid Link . 3 Conventions Used in Pro Tools Documentation . 4 Resources . 5 Chapter 2. Installing and Authorizing Avid Plug-Ins. 6 Installing Plug-Ins for Pro Tools and Media Composer . 6 Installing Plug-Ins from the Avid Marketplace. 6 About iLok . 7 Authorizing Avid Audio Plug-Ins . 7 Removing Plug-Ins. 8 Chapter 3. Adjusting Plug-In Controls . 9 Dragging Plug-In Controls. 9 Editing Control Values . 10 Dragging in Graphic Displays . 10 Toggle Controls . 10 Adjusting Controls with Fine Resolution. 11 Resetting Controls to Default Values . 11 General Effects Controls. 11 MIDI Control . -

AGENDA Regular City Council Meeting Monday, December 2, 2019, 6:00 PM Council Chambers, 116 First Street, Neptune Beach, Florida

AGENDA Regular City Council Meeting Monday, December 2, 2019, 6:00 PM Council Chambers, 116 First Street, Neptune Beach, Florida 1. CALL TO ORDER / ROLL CALL / PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE 2. AWARDS / PRESENTATIONS / RECOGNITION OF GUESTS A. Swearing In CeremonyOfficer Christian Griffin 3. APPROVAL OF MINUTES A. November 4, 2019, Regular City Council Meeting November 18, 2019, Special City Council Meeting November 18, 2019, Workshop City Council Meeting 4. COMMUNICATION / CORRESPONDENCE / REPORTS Mayor City Attorney City Council City Clerk City Manager Departmental Reports 5. COMMENTS FROM THE PUBLIC 6. CONSENT AGENDA / NONE 7. VARIANCES / SPECIAL EXCEPTIONS / DEVELOPMENT ORDERS A. CDB 1911, Application for Development Permit review as outlined in Chapter 27, Article 2 of the Unified Land Development Code of Neptune Beach for Brewhound Coffee Bar Company for the property known as 1848 Kings Circle South (RE#1732900000). This property is in the C2 Zoning District. The applicant is proposing to build an 8' by 8' accessory structure to serve as a kiosk for customer checkin and reception. B. CDB 1912, Application for Replat as outlined in Chapter 27, Article 3 of the Unified Land Development Code of Neptune Beach for 324 Myrtle Street, LLC. The property is currently known as 324 Myrtle Street, (RE# 1729760000). The subject property is located on the northeast corner of Third and Myrtle Streets. The applicants are requesting to demolish the existing duplex and subdivide the property into two conforming lots that will front on Myrtle Street. -

America's Story Vol. 1

America's Story One - interior 1st.indd 1 1/16/17 11:42 AM First printing: February 2017 Image Credits Sixth printing: October 2020 All images are public domain (PD- US, PD-Art, and LOC), except for: Copyright © 2017 by Angela O'Dell and Master Books®. All rights reserved. No part Science Photo Library - 22BL, 23B of this book may be reproduced, copied, Shutterstock - 5, 6, 10, 11, 12TL, 12C, broadcast, stored, or shared in any form 12B, 13TL, 13TR, 14R, 15, 18T, 21, 26T, 26B, 34R, 35, 51T, 51B, 53, 54R, whatsoever without written permission 55, 59, 61, 62BL, 64L, 64R, 71, 74L, from the publisher, except in the case of 74R, 75R, 76B, 84L, 84R, 94l, 94R, Author: Angela O’Dell brief quotations in articles and reviews. For 101B, 102T, 102BR, 103TR, 104R, Master Books Creative Team: 105, 109B, 114L, 115, 117B, 119T, information write: 119B, 120, 123BR, 124R, 125, 135, Editor: Shirley Rash Master Books®, P.O. Box 726, 144L, 147T, 154L, 154R, 155, 157B, Green Forest, AR 72638 160, 164R, 165, 166, 167T, 169T, Design: Diana Bogardus 170T, 174R, 175, 176B, 182TR, 184R, ® Cover Design: Diana Bogardus Master Books is a division of the 185, 195, 196T, 196B, 199, 201B, New Leaf Publishing Group, Inc. 204R, 208, 211B, 214R, 215, 224R, Copy Editors: 225, 230B, 246R, 247, 249C, 249B, Judy Lewis 250T, 251BR, 252T, 254TR, 254BR, ISBN: 978-0-89051-979-0 255, 258, 264B, 266, 267T, 269, 274R, Willow Meek 275, 276, 279T, 279B, 282B ISBN: 978-1-61458-583-1 (digital) Curriculum Review: SuperStock- front cover Library of Congress Number: 201795874 Kristen Pratt Wikimedia Commons: Images from Laura Welch Wikimedia Commons are used under Diana Bogardus Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations the CC0 1.0, CC BY-SA 2.0 DE, CC- BY-SA-3.0 license or the GNU Free are from the New King James Version of the Documentation License, Version 1.3.