Radical Politics in Hong Kong: Can Business Make a Difference? James T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Appointment of Committee and Advisers on Facilities for West Kowloon C

Appointment of committee and advisers on facilities for West Kowloon C... 第 1 頁,共 3 頁 WKCD-251 Appointment of committee and advisers on facilities for West Kowloon Cultural District ****************************************************** ****** The Government announced today (April 6) the Chief Executive has appointed members to the Consultative Committee and its three Advisory Groups on the Core Arts and Cultural Facilities of the West Kowloon Cultural District. The appointment commenced today (April 6) and will last till the end of 2006. The Chief Secretary for Administration, Mr Rafael Hui, said the main task of the committee was to re-examine and re-confirm if appropriate, the need for the core arts and cultural facilities for the WKCD as defined in the Invitation for Proposals (IFP) issued in September 2003 to meet the aspirations and needs of the local arts and cultural community and attract visitors. The committee would also advise the Chief Executive on the justifications for the core arts and cultural facilities and other types of arts and cultural facilities as appropriate and necessary to be provided at the WKCD and the financial implications for developing and operating these facilities. "The Consultative Committee and its three Advisory Groups comprise members from the arts, cultural, entertainment and tourism sectors," Mr Hui said. "They are mainly professionals or practitioners in relevant fields who would be in the best position to help re-examine the core arts and cultural facilities for the WKCD." The Chief Secretary will chair the Consultative Committee. The three Advisory Groups set up under the Consultative Committee, namely the Performing Arts and Tourism Advisory Group, the Museums Advisory Group and the Financial Matters Advisory Group, will be chaired by the Hon Selina Chow Liang Shuk-yee, the Hon Victor Lo Chung-wing and the Hon Marvin Cheung Kin-tung respectively. -

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL-15 July 1987 2027

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL-15 July 1987 2027 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 15 July 1987 The Council met at half-past Two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR DAVID CLIVE WILSON, K.C.M.G. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY MR. DAVID ROBERT FORD, L.V.O., O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY (Acting) MR. JOHN FRANCIS YAXLEY, J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. MICHAEL DAVID THOMAS, C.M.G., Q.C. THE HONOURABLE LYDIA DUNN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEN SHOU-LUM, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER C. WONG, C.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HO KAM-FAI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HU FA-KUANG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG PO-YAN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEPHEN CHEONG KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG YAN-LUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARIA TAM WAI-CHU, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HENRIETTA IP MAN-HING, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN YING-LUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. PAULINE NG CHOW MAY-LIN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER POON WING-CHEUNG, M.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE YEUNG PO-KWAN, C.P.M., J.P. -

Laws Governing Homosexual Conduct

THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG REPORT LAWS GOVERNING HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT (TOPIC 2) LAWS GOVERNING HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT WHEREAS : On 15 January 1980, His Excellency the Governor of Hong Kong Sir Murray MacLehose, GBE, KCMG, KCVO in Council directed the establishment of the Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong and appointed it to report upon such of the laws of Hong Kong as may be referred to it for consideration by the Attorney General and the Chief Justice; On 14 June 1980, the Honourable the Attorney General and the Honourable the Chief Justice referred to this Commission for consideration a Topic in the following terms : "Should the present laws governing homosexual conduct in Hong Kong be changed and, if so, in what way?" On 5 July 1980, the Commission appointed a Sub-committee to research, consider and then advise it upon aspects of the said matter; On 28 June 1982, the Sub-committee reported to the Commission, and the Commission considered the topic at meetings between July 1982 and April, 1983. We are agreed that the present laws governing homosexual conduct in Hong Kong should be changed, for reasons set out in our report; We have made in this report recommendations about the way in which laws should be changed; i NOW THEREFORE DO WE THE UNDERSIGNED MEMBERS OF THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG PRESENT OUR REPORT ON LAWS GOVERNING HOMOSEXUAL CONDUCT IN HONG KONG : Hon John Griffiths, QC Hon Sir Denys Roberts, KBE (Attorney General) (Chief Justice) (祈理士) (羅弼時) Hon G.P. Nazareth, OBE, QC Robert Allcock, Esq. -

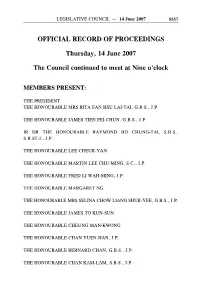

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 14 June

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 14 June 2007 8865 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 14 June 2007 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. 8866 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 14 June 2007 THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE YEUNG SUM THE HONOURABLE LAU CHIN-SHEK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. -

香港特別行政區排名名單 the Precedence List of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

二零二一年九月 September 2021 香港特別行政區排名名單 THE PRECEDENCE LIST OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION 1. 行政長官 林鄭月娥女士,大紫荊勳賢,GBS The Chief Executive The Hon Mrs Carrie LAM CHENG Yuet-ngor, GBM, GBS 2. 終審法院首席法官 張舉能首席法官,大紫荊勳賢 The Chief Justice of the Court of Final The Hon Andrew CHEUNG Kui-nung, Appeal GBM 3. 香港特別行政區前任行政長官(見註一) Former Chief Executives of the HKSAR (See Note 1) 董建華先生,大紫荊勳賢 The Hon TUNG Chee Hwa, GBM 曾蔭權先生,大紫荊勳賢 The Hon Donald TSANG, GBM 梁振英先生,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon C Y LEUNG, GBM, GBS, JP 4. 政務司司長 李家超先生,SBS, PDSM, JP The Chief Secretary for Administration The Hon John LEE Ka-chiu, SBS, PDSM, JP 5. 財政司司長 陳茂波先生,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, MH, JP The Financial Secretary The Hon Paul CHAN Mo-po, GBM, GBS, MH, JP 6. 律政司司長 鄭若驊女士,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, SC, JP The Secretary for Justice The Hon Teresa CHENG Yeuk-wah, GBM, GBS, SC, JP 7. 立法會主席 梁君彥議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The President of the Legislative Council The Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBM, GBS, JP - 2 - 行政會議非官守議員召集人 陳智思議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Convenor of the Non-official The Hon Bernard Charnwut CHAN, Members of the Executive Council GBM, GBS, JP 其他行政會議成員 Other Members of the Executive Council 史美倫議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon Mrs Laura CHA SHIH May-lung, GBM, GBS, JP 李國章議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP Prof the Hon Arthur LI Kwok-cheung, GBM, GBS, JP 周松崗議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon CHOW Chung-kong, GBM, GBS, JP 羅范椒芬議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon Mrs Fanny LAW FAN Chiu-fun, GBM, GBS, JP 黃錦星議員,GBS, JP 環境局局長 The Hon WONG Kam-sing, GBS, JP Secretary for the Environment # 林健鋒議員,GBS, JP The Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP 葉國謙議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon -

1 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL -- 12 December 1990

1 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL -- 12 December 1990 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL -- 12 December 1990 1 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 12 December 1990 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR DAVID CLIVE WILSON, K.C.M.G. THE CHIEF SECRETARY and THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY* THE HONOURABLE SIR PIERS JACOBS, K.B.E., J.P. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL THE HONOURABLE JEREMY FELL MATHEWS, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEPHEN CHEONG KAM-CHUEN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG YAN-LUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARIA TAM WAI-CHU, C.B.E., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE HENRIETTA IP MAN-HING, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN YING-LUN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER POON WING-CHEUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHENG HON-KWAN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHUNG PUI-LAM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE HO SAI-CHU, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HUI YIN-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, Q.C., J.P. * The Financial Secretary doubled up as Chief Secretary THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, J.P. THE HONOURABLE NGAI SHIU-KIT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PANG CHUN-HOI, M.B.E. -

Report Are Those of the Authors and Do Not Necessarily Represent the Opinions of Civic Exchange

Past and future justifications for Functional Constituencies – An Analysis through the Performance of Functional Constituencies Legislators (2004-2006) Marcos Van Rafelghem and P Anson Lau Past and Future Justifications for Functional Constituencies – An analysis through the performance of functional constituency legislators in 2004-2006 Marcos Van Rafelghem and P Anson Lau November 2006 www.civic-exchange.org Civic Exchange Room 701, Hoseinee House, 69 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong. Tel: (852) 2893 0213 Fax: (852) 3105 9713 Civic Exchange is a non-profit organisation that helps to improve policy and decision-making through research and analysis. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Civic Exchange. Preface This research paper seeks to continue our work in understanding the Functional Constituencies as an important feature of Hong Kong’s political system. As a result of our extensive research on the subject from 2004, the issues and problems surrounding the election system that generates functional representation in the Hong Kong Legislative Council, the performance of functional legislators, and the impacts they and the election system have on Hong Kong’s development as a whole are becoming clear. The challenge facing Hong Kong today is what to do with the Functional Constituencies as the political system continues to evolve towards universal suffrage. This paper concludes that by developing political parties in Hong Kong the various political and ideological differences would ensure the various interests are still represented in the legislature without recourse to the problematic Functional Constituencies. The conclusion points to the need for work on alternative solutions to the Functional Constituencies. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 7 June

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 7 June 2007 8055 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 7 June 2007 The Council continued to meet at half-past Two o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, G.B.S., J.P. 8056 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 7 June 2007 THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE YEUNG SUM THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHOY SO-YUK, J.P. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/BC/18/98

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)560/99-00 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/BC/18/98 Bills Committee on Chinese Medicine Bill Minutes of meeting held on Thursday, 27 May 1999 at 8:30 am in Conference Room B of the Legislative Council Building Members : Prof Hon NG Ching-fai (Chairman) Present Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Michael HO Mun-ka Hon LEE Kai-ming, JP Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP Hon Mrs Selina CHOW LIANG Shuk-yee, JP Hon Ronald ARCULLI, JP Hon CHAN Yuen-han Dr Hon LEONG Che-hung, JP Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP Members : Hon David CHU Yu-lin Absent Hon HO Sai-chu, JP Hon YEUNG Yiu-chung Hon Ambrose LAU Hon-chuen, JP Hon CHOY So-yuk Hon SZETO Wah Hon LAW Chi-kwong, JP Public Officers : Mr Gregory LEUNG, JP Attending Deputy Secretary for Health and Welfare (1) Miss Eliza YAU Principal Assistant Secretary for Health and Welfare (Medical) 1 Miss Miranda NG - 2 - Action Senior Assistant Law Draftsman, Department of Justice Dr LEUNG Ting-hung Assistant Director of Health (Traditional Chinese Medicine) Clerk in : Ms Doris CHAN Attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2) 4 Staff in : Mr LEE Yu-sung Attendance Senior Assistant Legal Adviser Ms Joanne MAK Senior Assistant Secretary (2) 4 _____________________________________________________________________ I. Internal Discussion Proposed visit to the Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine Members discussed and agreed to pay a visit to the Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine and to meet other parties concerned with regulation of Chinese medicine on Sunday, 13 June 1999. -

Is Hong Kong Developing a Democratic Political Culture?

China Perspectives 2007/2 | 2007 Hong Kong. Ten Years Later Is Hong Kong Developing a Democratic Political Culture? Jean-Philippe Béja Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1583 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1583 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 avril 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Jean-Philippe Béja, « Is Hong Kong Developing a Democratic Political Culture? », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/2 | 2007, mis en ligne le 08 avril 2008, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1583 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1583 © All rights reserved Special feature s e v Is Hong Kong Developing a i a t c n i e Democratic Political Culture? h p s c r e JEAN-PHILIPPE BÉJA p ong Kong will not be ready for universal suf - who stress their belonging to China, they are still in a minor - frage until around 2022 because its people ity. This justifies the approach of this article, which will be “H lack a sense of national identity ((1) ”. This dec - to study those elements which are specific to Hong Kong’s laration by Ma Lik, chairman of the pro-Beijing Democratic political culture. Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, shows how the question of national identity is so central to The emergence of a specific political debate in Hong Kong that it sets the terms for the Hong Kong political culture territory’s democratic development, even though this is al - ready laid down in the Basic Law.