3. Ambush Marketing……………………………………………………………………...25 3.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning to Löw Again

22 The German Times – Life April 2019 field. Toward the end of the tournament, it was to follow his will. And when he dared to venture BY THOMAS KISTNER easy to see that these two stalwarts were com- into the strategic arena with his own ideas, he often pletely overwhelmed, with each player committing fell flat on his face. Even worse than his outing at oachim Löw got his act together just in again Löw to Learning a bizarre and obvious handball in his own penalty the European Championship in France in 2016 time. After balking and bristling at calls for Cup in Russia, at the 2018 Soccer World early exit Germany’s After area. In the quarterfinals, Italy took advantage was the previous European Championship in 2012 Jchange, he’s finally put the German national of Boateng’s lapse to knot the game at 1 with a in Poland/Ukraine, where Löw chose the wrong soccer team on a different track. Whether this penalty kick. Luckily for the DFB team, they were players and coached the team so hopelessly into proves effective has yet to be seen, but at least able to go on to win that match on penalties. When the ground during the semifinal against Italy that head coach Joachim Löw finally realized it was time to build a new team they got off to a good start with a convincing Schweinsteiger deliberately had a handball in the their defeat was already secured at the halftime 3:2 win at the European Championship quali- semifinal against France, however, they weren’t break. -

Hotel Bayarena Leverkusen

HOTEL BAYARENA Leverkusen NICHT NUR BESSER. ANDERS. LOGENPLAtz – FÜR BUSINESS UND SPORT. Eingebettet in die Nordkurve des Stadions vom Bundesligisten Bayer 04 Leverkusen ist das Lindner Hotel BayArena nicht nur Deutschlands erstes Stadionhotel, sondern auch DIE Location für Business Traveller, Städtebummler & Fußballfans in Leverkusen! Modern gemütliches Design in allen Zimmern und Suiten und die Sportsbar in der 6-geschossigen Atrium Eventhalle sorgen für (ent)spannende Aufenthalte. First Class Stadion Logen und ein- zigartige Konferenz- & Veranstaltungsflächen mit sensationellem Blick ins Stadion, ausgestattet mit modernster Konferenz- und Medientechnik, garantieren einmalige Events. Das Lindner Hotel BayArena ist für jeden Anlass und in jeder Beziehung Ihr Logen- platz für Business und Sport! BOX SEAT – FOR BUSINESS AND SPORTS. Built into the north stand of the home stadium of the Bayer 04 Leverkusen national league football team, the Lindner Hotel BayArena is not only Germany‘s first stadium hotel but also THE place in Leverkusen for business travelers, visitors to the city and football fans to be. The contemporarily cozy design of all the rooms and suites and the sports bar in the 6-story atrium event hall extend the promise of a relaxing yet exciting stay. First-class stadium boxes and unique conference and event areas with a sensational view into the stadium and equipped with state-of-the-art conferencing and media technology serve as a guarantee for one-of-a-kind events. The Lindner Hotel BayArena is in every respect your „box seat“ for any occasion, be it business or sports related. ZIMMER 121 modern gestaltete Zimmer, davon 12 großzügige Studios. Alle mit individuell regelbarer Klimaanlage und kleinem Arbeits- bereich, ISDN-Telefon mit Voice-Mailbox, Telefax-, Modem- und Internetanschluss, WLAN-Internettechnik. -

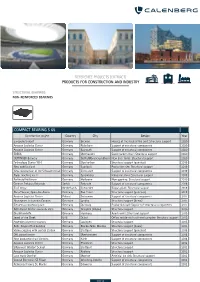

Reference List Construction and Industry

REFERENCE PROJECTS (EXTRACT) PRODUCTS FOR CONSTRUCTION AND INDUSTRY STRUCTURAL BEARINGS NON-REINFORCED BEARINGS COMPACT BEARING S 65 Construction project Country City Design Year Europahafenkopf Germany Bremen Houses at the head of the port: Structural support 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Paderborn Support of structural components 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Bayreuth Support of structural components 2020 EDEKA Germany Oberhausen Supermarket chain: Structural support 2020 OETTINGER Brewery Germany Gotha/Mönchengladbach New beer tanks: Structural support 2020 Technology Center YG-1 Germany Oberkochen Structural support (punctual) 2019 New nobilia plant Germany Saarlouis Production site: Structural support 2019 New construction of the Schwaketenbad Germany Constance Support of structural components 2019 Paper machine no. 2 Germany Spremberg Industrial plant: Structural support 2019 Parkhotel Heilbronn Germany Heilbronn New opening: Structural support 2019 German Embassy Belgrade Serbia Belgrade Support of structural components 2018 Bio Energy Netherlands Coevorden Biogas plant: Structural support 2018 NaturTheater, Open-Air-Arena Germany Bad Elster Structural support (punctual) 2018 Amazon Logistics Center Poland Sosnowiec Support of structural components 2017 Novozymes Innovation Campus Denmark Lyngby Structural support (linear) 2017 Siemens compressor plant Germany Duisburg Production hall: Support of structural components 2017 DAV Alpine Centre swoboda alpin Germany Kempten (Allgäu) Structural support 2016 Glasbläserhöfe -

STADION SC FREIBURG Plausibilitätsprüfung Baukostenschätzung Stadion Freiburg

Plausibilitätsprüfung - IFS Kostenschätzung - 03.09.2014 STADION SC FREIBURG Plausibilitätsprüfung Baukostenschätzung Stadion Freiburg Vorgehensweise zur Plausibilisierung der IFS Kostenschätzung PROPROJEKT wurde im Juli 2014 von der Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau mit der Plausibilisierung der von IFS erstellten Baukostenschätzung für den Neubau eines Stadions für den SC Freiburg beauftragt. Hierfür werden zwei unterschiedliche und voneinander unabhängige Ansätze gewählt: 1. Benchmarks (Top-Down Plausibilisierung): › Erhebung der Baukosten von Stadionneubauten (bzw. Umbauten) der 1.-3. Liga. › Untersuchung von 26 Stadien, welche ab dem Jahre 2000 in Deutschland neu bzw. grundlegend umgebaut wurden. › Ermittlung eines – auf dieser Datengrundlage basierenden – stadionspezifischen Kennwerts „Baukosten pro Sitzplatz“ als vergleichende Benchmark. 2. Baukostenschätzung (Bottom-Up Plausibilisierung): › Überprüfung der Einzelpositionen der IFS Baukostenschätzung auf Plausibilität. › Erstellung einer eigenen Baukostenschätzung für ein Stadion in vergleichbarer Kapazität und Qualität wie das Stadion Freiburg auf Basis eigener und in der Praxis bewährter Kostenkennwerte für Stadionneubauten. › Gegenüberstellung mit den Gesamtkosten der IFS Kostenschätzung. Plausibilitätsprüfung › Stadion SC Freiburg 3. September 2014 › 2 Inhalt PLAUSIBILITÄTSPRÜFUNG 1 - Benchmarks - Vergleichswerte Stadionneubauten 2 - Baukostenschätzung - Eigenansatz PROPROJEKT 3 - Fazit 1 - Benchmarks Vergleichswerte von 26 Stadionneubauten Vorgehensweise zur Ermittlung der Benchmarks -

FC Bayern Munich Principles

FC Bayern Munich Principles Bayern Munich's club motto, "mia san mia," is a Bavarian phrase meaning "we are who we are." Bayern Munich is the biggest and most storied club in German soccer history. Bayern Munich has an unprecedented 23 league and 16 national cup trophies in its display case. Good things come in threes at FC Bayern. Led by the legendary Franz Beckenbauer, a player so good that he invented the modern sweeper position, Bayern Munich won three straight European Cups from 1974‐1976. In 2013, the club completed a historic Treble, capturing the German Bundesliga, DFB‐Pokal league cup and UEFA Champions League crowns. In addition to other strong benefits, the FC Bayern Munich’s philosophy, which is, shared throughput the FC Bayern world including their players, staff and fans mirrors the beliefs that the Parsippany Soccer Club has. We all need to remember these principles and be proud that we can share the same philosophy and be affiliated with one of the biggest clubs in the world. Please take a moment and read through these principles and you will understand why we are affiliated with such a powerful but yet very humbled soccer club. The 16 principles of FC Bayern are explained below and are an accurate description of who Bayern really are. Again, they form a philosophy which players, staff and fans should live alike. ▪ Mia san ein Verein – We are one club: We are all formed by the club’s history, we are all involved in its development and we share the same values. -

Bachelorarbeit Sarah Herrmann Der Wirtschaftliche Betrieb

Der wirtschaftliche Betrieb eines Stadions Ableitung von Einflusskriterien aus den betriebswirtschaftlichen Funktionsbereichen Bachelorarbeit im Studiengang Sportmanagement an der Ostfalia Hochschule für angewandte Wissenschaften Eingereicht von: Herrmann, Sarah 40895339 Erster Prüfer: Prof. Dr. Ronald Wadsack Zweiter Prüfer: Dr. Otmar Dyck Eingereicht am: 17.01.2012 II Inhaltsverzeichnis Abbildungsverzeichnis ...................................................................................................... V Tabellenverzeichnis .......................................................................................................... V Abkürzungsverzeichnis ................................................................................................... VII 1 Einleitung ........................................................................................................................ 8 1.1 Leitidee und Ziel dieser Arbeit............................................................................. 8 1.2 Vorgehensweise ................................................................................................. 8 2 Grundlagen Stadion ........................................................................................................ 9 2.1 Grundlagen des Stadions als Immobilie .............................................................. 9 2.1.1 Definition Stadion ................................................................................... 9 2.1.2 Stadion als Sportstätte ......................................................................... -

Ausgabe 06 / Saison 19/20 • Fortuna Düsseldorf • Auflage: 1.500 / Gegen Freiwillige Spende

Ausgabe 06 / Saison 19/20 • Fortuna Düsseldorf • Auflage: 1.500 / gegen freiwillige Spende TERMINE: 23.11.2019 15:30 Uhr 29.11.2019 20:30 Uhr SV Werder Bremen - FC Schalke 04 FC Schalke 04 - 1.FC Union Berlin Weserstadion Arena AufSchalke Glückauf Schalker, nach drei sieglosen Spielen in der Liga konnte letzten Sonntag in Augsburg die wichtigen drei Punkte einge- fahren werden. Heute gilt es gegen die Landeshauptstadt NRWs daran anzuknüpfen und uns in den oberen Gefilden der Tabelle festzusetzen. Das Cover ziert wie immer im November Charly Neumann. Sein Todestag jährt sich am kommenden Montag bereits zum elften Mal. Mit diesem Cover wollen wir aber nicht bloß Charly Neumann gedenken. Er steht für uns stellvertretend für alle verstorbenen Schalker. Ruhet in Frieden, hier unten war es besser mit euch! In der Derby Ausgabe des Schalker Kreisels war ein Interview mit Marketingvorstand Alexander Jobst zu lesen. Einige seiner Aussagen, explizit die zum Thema eingetragener Verein, ließen uns aufhorchen. Aus diesem Grund befassen wir uns in diesem Blauen Brief genauer mit Jobst Worten und widmen dem Interview einen eigenen Text. Passenderweise in der Rubrik „Eingetragener Verein“. FC Schalke 04 e.V. - Borussia Dortmund GmbH & Co. KGaA 0:0 (0:0) Endlich war es wieder so weit. Auf den Tag genau, nach sechs Jahren, durfte die Dortmunder Szene wieder nach Gelsenkirchen reisen. Alles Einwirken, auch von unserer Seite, nutzte nichts und die lokalen Stadionverbote wur- den die Jahre über vom Verein durchgedrückt. Es ist einfach nicht dasselbe, wenn ein richtiger Gegner gegenüber fehlt. Und so war die Motivation nun natürlich ungleich höher als bei den vergangenen Spielen! Bereits in den Wochen davor konnten wir beim Köln-Heimspiel einen Stich setzen, als die Kölner Stadionverbotler inklusive schwarzgelber Unterstützung deutlich unter die Räder kamen. -

Nr. Gesamt Stadt Verein Stadionname Baden-Württemberg 1 Aalen Vfr

Nr. Gesamt Stadt Verein Stadionname Baden-Württemberg 1 Aalen VfR Aalen Waldstadion 2 Abtsgmünd-Hohenstadt SV Germania Hohenstadt Sportplatz 3 Backnang TSG Backnang Etzwiesenstadion 4 Baiersbronn SV Baiersbronn Sportzentrum 5 Balingen TSG Balingen Austadion 6 Ditzingen TSF Ditzingen Stadion Lehmgrube 7 Eppingen VfB Eppingen Hugo-Koch-Stadion 8 Freiburg SC Freiburg Dreisamstadion 9 Freiburg SC Freiburg Amateure Möslestadion 10 Großaspach SG Sonnenhof Großaspach Sportplatz Aspach-Fautenhau 11 Großaspach SG Sonnenhof Großaspach Mechatronik-Arena 12 Heidenheim 1. FC Heidenheim Voith-Arena 13 Heilbronn VfR Heilbronn Frankenstadion 14 Heuchlingen TV Heuchlingen Sportplatz 15 Ilvesheim SpVgg Ilvesheim Neckarstadion 16 Karlsruhe Karlsruher SC Wildparkstadion 17 Karlsruhe Karlsruher SC Amateure Wildparkstadion Platz 4 18 Kirchheim / Teck VfL Kirchheim / Teck Stadion an der Jesinger Allee 19 Ludwigsburg SpVgg Ludwigsburg Ludwig-Jahn-Stadion 20 Mannheim VfR Mannheim Rhein-Neckar-Stadion 21 Mannheim SV Waldhof Mannheim Carl-Benz-Stadion 22 Mannheim SV Waldhof Mannheim II Seppl-Herberger-Sportanlage 23 Metzingen TuS Metzingen Otto-Dipper Stadion 24 Mühlacker FV 08 Mühlacker Stadion "Im Käppele" 25 Nöttingen FC Nöttingen Panoramastadion 26 Offenburg Offenburger FV Karl-Heitz-Stadion 27 Pforzheim 1. FC Pforzheim Stadion Brötzinger Tal 28 Pfullendorf SC Pfullendorf Waldstadion 29 Reutlingen SSV Reutlingen Stadion a. d. Kreuzeiche 30 Ruppertshofen TSV Ruppertshofen Sportplatz 31 Sandhausen SV Sandhausen Hardtwaldstadion 32 Schäbisch Gmünd 1. FC Normannia -

MUCH MORE THAN a STADIUM Events | Meetings | Conferences BAYARENA-PLUS Always on the Ball

MUCH MORE THAN A STADIUM Events | Meetings | Conferences BAYARENA-PLUS Always on the ball Versatile and with an array of extraordinary possibili- Görresstraße ties, the BayArena is the perfect setting for professional business events and impressive large-scale functions. It is the allrounder of modern football stadiums and provides sophisticated technology and an abundance of space all the way to the catacombs. You benefit from an ideal playing field for functions, workshops and meetings when there is a break from the usual football action. We have the perfect set-up for your team’s match. You determine the line-up, we recommend the right tactic and ensure the very best conditions. At the venue of the beautiful game your business takes centre stage – including extra time. The stadium meets the highest requirements for debriefing and regenera- tion. The BayArena – the perfect venue for your business event. EAST Bismarckstraße 21 21 22 23 NORTH 11 SOUTH 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 5 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 Public parking lot from the 19 Marienburger Straße 1 Marienburger Straße WEST Tannenbergstraße AREAS | MEETINGS & CONFERENCES AREAS | EVENTS 1 Fankurve 11 Logen Süd 16 Press Bistro 2 Talentschuppen 12 Gastbereich Nord 17 Premium-Lounge Das Auge 3 Elfmeter 13 Gastbereich Süd 18 Rasenkante 4 Heimspiel 14 19nullvier-Loungenzraum II 19 Piazza 5 – 9 Conference rooms I–V Nord 15 Press conference room 20 Beer garden 10 Auswärtsspiel 21 Eventloge I+II 22 Schwadbud 23 Barmenia-Lounge ANYTHING BUT BUSINESS AS USUAL Our exclusive rooms and your opportunities 4 The Heimspiel room with branded multimedia Our lounge areas are a perfect place for a breather during the match Large assembly for up to 270 persons Well-equipped: from writing pads to high-end presentation technology Video walls with customised content 5 A PERFECT OVERVIEW THE RIGHT LINE-UP FOR EVERY OCCASION MULTIMEDIA PERFECT SERVICE AND TOP-NOTCH EQUIPMENT. -

Årsskriftet for 2013

VEJLE BOLDKLUB ÅRSSKRIFT 2013 60. årgang LEVERANDØR TIL HOS OS KAN DU KØBE DEN SIDSTE NYE SPILLETRØJE Sport24 er fyldt med originale spillebluser, shorts, strømper m.m. Gør også en god han- del på SPORT24.DK Bryggen - Søndertorv 2 - 7100 Vejle - Tlf. 3021 3290 Torvegade 9 - 7100 Vejle - Tlf. 3021 3280 2 Forord Kære læser, omkring det at spille fodbold. I årsskriftet vil vi komme omkring de enkelte I år kan Årsskriftet for Vejle Boldklub fejre 60 hold, og gå i dybden med resultater, stil- års jubilæum. En særdeles flot tradition har linger, udvalgte oplevelser, portrætter og med en kæmpe indsats fra mange gode folk meget andet. i og omkring klubben endnu engang fundet vej i trykken og dermed vej til vore trofaste På det administrative og organisatoriske læsere. plan har vi i det meste af 2013 kørt med en Udgave nr. 60, som du sidder med i hæn- firemands bestyrelse. Opgaverne er fordelt derne, er dokumentation for endnu et år, på nogle fælles opgaver og nogle specifikke hvor Vejle Boldklub har vist sig frem på såvel ansvarsområder. En af de helt store opgaver bredde- som elitefodboldscenen. Det er også har været at få defineret og finde beman- en bekræftelse på, at Vejle Boldklub er en ding til en ny struktur. Det arbejde er nu ved traditionsrig og fremtidsorienteret klub. at være tilendebragt, ja faktisk er en del af Det er en stor glæde for anden gang at få lov det allerede implementeret og fungerende. at skrive forordet til et Årsskrift, som i den Økonomien er tilbage på sporet, og vi kan grad er unikt i dagens Fodbold-Danmark. -

Bezahlsysteme in Stadien Und Arenen

PAYMENT BEZAHLSYSTEME IN STADIEN UND ARENEN STADIONWELT INSIDE UNIORG Mit ZUKUNFTSORIENTIERTEN KASSENLÖSUNGEN das Wesentliche im Fokus - Ihre Fans! individuelle Schnellauswahl | zentrale Gutscheinverwaltung bargeldloses Bezahlen | gemischter Warenkorb on- und offline fähig | Design Hardware Zeiterfassung | integriert oder stand-alone Fokusthema „rechtssichere Kassen in Stadien und Arenen“ in unserem kostenlosen Info-Webinar! www.SBO4Sports.de Gerade in den Stoßzeiten wirkt sich das bargeldlose Bezahlen positiv „ aus. Dank SAP® Customer Checkout werden die Fans zügig mit Speisen und Getränken versorgt. Michael Becker, Projektmanager und Leiter Marketing, SV Sandhausen 1916 e.V. Lesen Sie hier die gesamte Erfolgsgeschichte: www.sbo4mittelstand.de/sv-sandhausen ANSPRECHPARTNER Julian Wehmann | Cloud Business Development | [email protected] | +49 160 95717486 UNIORG Gruppe | Lissaboner Allee 6-8 | 44269 Dortmund | www.uniorg.de | [email protected] | +49 231 9497-0 PAYMENT INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Bezahlsysteme in der 1. Fußball-Bundesliga (2016/17) Verein Stadion Bezahlmethode Anbieter Bezahlkarte (offenes System), Girocard, Barzahlung, 1. FC Köln RheinEnergieSTADION Bezahlkarte (offenes System), Girocard, Barzahlung, Sparkasse KölnBonn/Kreissparkasse Köln Geldkarte 1. FSV Mainz 05 OPEL ARENA Bezahlkarte (offenes System), Geldkarte Sparkasse Mainz Bayer 04 Leverkusen BayArena Bezahlkarte (offenes System), Geldkarte Sparkasse Leverkusen Borussia Dortmund SIGNAL IDUNA PARK Bezahlkarte (geschlossenes System), Barzahlung, Hausintern Borussia Dortmund SIGNAL -

Amos Pieper Dr. Werner Krutsch Eva Immerheiser

SONDERHEFT 2020 VDV-PROFI VDV-MEDIZIN VDV-PRÄVENTION Amos Pieper Dr. Werner Krutsch Eva Immerheiser Bielefelds Aufsteiger Experte der Task- DFB-Juristin über über den Zusammen- Force über den Schulungen gegen halt der Profis Gesundheitsschutz Match-Fixing www.spielergewerkschaft.de FAKE Hintergründe und Aktuelles rund um den deutschen Profifußball. Bei uns aus erster Hand. DFL.de @DFL_Official DFL MAGAZIN E-Paper tomorrow.DFL.de DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga DFL_Fakten_NOV18_210x297_DFB_aktuell_39L300.indd 1 23.11.18 10:42 WIR PROFIS DAS MAGAZIN DER VDV SONDERHEFT 2020 VDV-ANSTOSS 3 Liebe Mitglieder, liebe Fußballfreunde, die Covid-19-Pandemie hat uns der Pandemie ihre Gesundheit Die Pandemie erfordert Flexi- vor ganz erhebliche Herausfor- aufs Spiel und kommen an vielen bilität. Durch den veränderten derungen gestellt. Erst durch Stellen den Klubs in wirtschaftli- Spielplan und die behördlichen große Anstrengungen und Ein- chen Belangen entgegen, um den Auflagen mussten auch wir unse- schränkungen ist es mittlerwei- Spielbetrieb wieder durchführen re Arbeit anpassen. So musste bei- le gelungen, die Ausbreitung zu können und somit tausende spielsweise die für Mai geplante des Virus zu reduzieren und Jobs im Fußballgeschäft zu si- Spielerversammlung leider ausfal- ein Stück weit zur Normalität chern. Somit muss klar sein, dass len und auch die Wahl der VDV 11 zurückzufinden. Auch wenn die Spielervertreter zukünftig als konnte erst im Juni starten. es weiterer Entbehrungen und feste Partner an den Entschei- Vorsichtsmaßnahmen bedarf, dungstisch gehören, wenn es da- Bereits weit vor dem Saisonende sehen wir zumindest Licht am rum geht, aus der Pandemie zu erreichten uns als Spielergewerk- Ende des Tunnels. schaft in diesem Jahr zahlreiche Anfragen zu unserem VDV-Profi- Die Pandemie hat auch die Arbeit camp sowie zu unseren weiteren der VDV stark beeinflusst.