Digital Devotions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hrc-Coming-Out-Resource-Guide.Pdf

G T Being brave doesn’t mean that you’re not scared. It means that if you are scared, you do the thing you’re afraid of anyway. Coming out and living openly as a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or supportive straight person is an act of bravery and authenticity. Whether it’s for the first time ever, or for the first time today, coming out may be the most important thing you will do all day. Talk about it. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Welcome 3 Being Open with Yourself 4 Deciding to Tell Others 6 Making a Coming Out Plan 8 Having the Conversations 10 The Coming Out Continuum 12 Telling Family Members 14 Living Openly on Your Terms 15 Ten Things Every American Ought to Know 16 Reference: Glossary of Terms 18 Reference: Myths & Facts About LGBT People 19 Reference: Additional Resources 21 A Message From HRC President Joe Solmonese There is no one right or wrong way to come out. It’s a lifelong process of being ever more open and true with yourself and others — done in your own way and in your own time. WELCOME esbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Americans Lare sons and daughters, doctors and lawyers, teachers and construction workers. We serve in Congress, protect our country on the front lines and contribute to the well-being of the nation at every level. In all that diversity, we have one thing in common: We each make deeply personal decisions to be open about who we are with ourselves and others — even when it isn’t easy. -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

Critical Queer Pedagogy for Social Justice in Catholic Education

LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations Spring April 2014 A Place to Belong: Critical Queer Pedagogy for Social Justice in Catholic Education Roydavid Villanueva Quinto Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Quinto, Roydavid Villanueva, "A Place to Belong: Critical Queer Pedagogy for Social Justice in Catholic Education" (2014). LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations. 202. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd/202 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOYOLA MARYMOUNT UNIVERSITY A Place to Belong: Critical Queer Pedagogy for Social Justice in Catholic Education by Roydavid Quinto A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the School of Education, Loyola Marymount University, in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education 2014 A Place to Belong: Critical Queer Pedagogy for Social Justice in Catholic Education Copyright © 2014 by Roydavid Quinto ABSTRACT A Place to Belong: Critical Queer Pedagogy for Social Justice in Catholic Education by Roydavid Quinto A growing number of gay and lesbian children attend Catholic schools throughout the United States; and an untold number of gay and lesbian children in Catholic schools are experiencing harassment, violence, and prejudice because of their sexual orientation or gender non-conformity. -

Gateway to the Syriac Saints: a Database Project Jeanne-Nicole Mellon Saint-Laurent Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Theology Faculty Research and Publications Theology, Department of 1-1-2016 Gateway to the Syriac Saints: A Database Project Jeanne-Nicole Mellon Saint-Laurent Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture, Vol. 5, No. 1 (2016): 183-204. Permalink. © 2016 St. John's College. Used with permission. 183 http://jrmdc.com Gateway to the Syriac Saints: A Database Project Jeanne-Nicole Mellon Saint-Laurent Marquette University, USA Contact: [email protected] Keywords: Syriac; hagiography; late antiquity; saints; manuscripts; digital humanities; theology; religious studies; history Abstract: This article describes The Gateway to the Syriac Saints, a database project developed by the Syriac Reference Portal (www.syriaca.org). It is a research tool for the study of Syriac saints and hagiographic texts. The Gateway to the Syriac Saints is a two-volume database: 1) Qadishe and 2) Bibliotheca Hagiographica Syriaca Electronica (BHSE). Hagiography, the lives of the saints, is a multiform genre. It contains elements of myth, history, biblical exegesis, romance, and theology. The production of saints’ lives blossomed in late antiquity alongside the growth of the cult of the saints. Scholars have attended to hagiographic traditions in Greek and Latin, but many scholars have yet to Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture Volume 5, Issue 1 (2016) https://jrmdc.com 184 discover the richness of Syriac hagiographic literature: the stories, homilies, and hymns on the saints that Christians of the Middle East told and preserved. It is our hope that our database will give scholars and students increased access to these traditions to generate new scholarship. -

A Queer Method for Theology. Genilma Boehler1 Summary This

1 The pot of gold: a queer method for theology. Genilma Boehler1 Summary This article proposes an approach to theology through the queer method. Queer theory leads to a paradigm shift in which the Other (masculine), the Other (feminine), as subjects, assume a key role from the theoretical perspectives born out of post- structuralism and deconstructivism, not as an identifying mold, but by objectifying post- identity. The novelty for Latin American theology is in the possibility of re- conceptualizing the subject not with fixed, stable aspects, but with ample freedom. This also broadens the possibility for other aspects of conceptual renewal surrounding theological discourse, and of metaphors about God. Keywords: Queer method, Theology, Feminism, Post-identity, Subjects. Introduction In 2006 as I was preparing my doctoral research project2, I was confronted with an intriguing doubt: to choose a theology able to interact with the poetry of Adélia Prado,3 which in its literary production possessed various combined elements such as Biblical ones, theological ones, together with body, the erotic, sensuality, sexuality, and daily life. It was exactly at that juncture, when I was searching for theologies that would work with the hermeneutical key of sexuality, when I stumbled across lesbian feminist theologies (which I was already familiar with, just not on a deeper level), gay theologies and queer theology. These theologies provided me with a key to transgression such as suspicion to deconstruct concepts that are well established yet at the same time simplify the very same theological discourse. I was presented with an extremely attractive landscape, as I learned and deepened my understanding of my readings of queer theory. -

Cataloging Service Bulletin 102, Fall 2003

ISSN 0160-8029 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/WASHINGTON CATALOGING SERVICE BULLETIN LIBRARY SERVICES Number 102, Fall 2003 Editor: Robert M. Hiatt CONTENTS Page DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGING Library of Congress Rule Interpretations 2 SUBJECT CATALOGING Subdivision Simplification Progress 48 Changed or Cancelled Free-Floating Subdivisions 49 Aboriginal Australians and Aboriginal Tasmanians 49 Subject Headings of Current Interest 50 Revised LC Subject Headings 50 Subject Headings Replaced by Name Headings 58 MARC Language Codes 58 ROMANIZATION Change in Yiddish Romanization Practice 58 Editorial postal address: Cataloging Policy and Support Office, Library Services, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540-4305 Editorial electronic mail address: [email protected] Editorial fax number: (202) 707-6629 Subscription address: Customer Support Team, Cataloging Distribution Service, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20541-4912 Subscription electronic mail address: [email protected] Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 78-51400 ISSN 0160-8029 Key title: Cataloging service bulletin Copyright ©2003 the Library of Congress, except within the U.S.A. DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGING LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RULE INTERPRETATIONS (LCRI) Cumulative index of LCRI to the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, second edition, 2002 revision, that have appeared in issues of Cataloging Service Bulletin. Any LCRI previously published but not listed below is no longer applicable and has been cancelled. Lines in the margins ( , ) of revised interpretations indicate where changes have occurred. -

True Colors Resource Guide

bois M gender-neutral M t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois gender-neutral M gender-neutralLOVEM gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch Birls polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme Asexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois M gender-neutral gender-neutral M t t F F ALLY Lesbian INTERSEX butch INTERSEXALLY Birls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual Asexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois LOVE gender-neutral M gender-neutral t F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois bois M gender-neutral M gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident -

On Gender, Sainthood, and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

History is not the past. It is the stories we tell about the past. How we tell these stories – triumphantly or self-critically, metaphysically or dialectically – has a lot to do with whether we cut short or advance our evolution as human beings. 01/21 – Grace Lee Boggs1 Part 1: Her Second Coming The Nailing of the Cross of St. Kümmernis depicts the fourteenth-century crucifixion of St. Wilgefortis, a medieval bearded female saint. The early nineteenth-century painting by Leopold Sam Richardson Pellaucher replaced another depiction of the saint at St. Veits Chapel in Austria, which had been destroyed by an overzealous Franciscan A Saintly Curse: clerk. Rather than the typical image of Wilgefortis already nailed to the cross, On Gender, Pellaucher opted to depict the scene leading up to her crucifixion, showing a distressed St. Sainthood, and Wilgefortis, an angry father who has ordered his daughter’s execution, and weeping female witnesses to the martyrdom.2 In choosing this Polycystic moment, the painting also equates Wilgefortis’s crucifixion with the rebirth or renewal associated Ovary with generic Christian interpretations of Christ. Christ’s crucifixion is symbolic of a second coming, his resurrection; Wilgefortis’s “second Syndrome e m coming” is perhaps representative of a o r d necessary escape to a separate life in order to n y begin anew. S y r ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊOriginally either a pagan noblewoman or the a v O princess of Portugal (her origins are disputed), c i t St. Wilgefortis was promised to a suitor by her n s o y 3 s c father. -

Investigation of Earthquake Behavior of the Church of St. Sergius and Bacchus in Istanbul/Turkey KOÇAK A1 and KÖKSAL T1 1Davutpaşa Mah

Advanced Materials Research Vols. 133-134 (2010) pp 821-829 © (2010) Trans Tech Publications, Switzerland doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.133-134.821 Investigation of Earthquake Behavior of the Church of St. Sergius and Bacchus in Istanbul/Turkey KOÇAK A1 and KÖKSAL T1 1Davutpaşa Mah. - İstanbul, Turkey [email protected] Abstract : In this study The Church of St. Sergius and Bacchus was modeled by Finite Element Me- thod and was put through various tests to determine its structural system, earthquake behavior and structural performance. The geometry of the structure, its material resistance and ground conditions isn’t enough to model a historical structure. Additionally, you need to calculate the dynamic charac- teristics of the structure with an experimental approach to come up with a more realistic and reliable model of the structure. Therefore, a measured drawing of the structure was acquired after detailed studies, material test- ing were made both at summer and winter to examine the seasonal changes and soil conditions were determined by bore holes and exploratory wells dug around the structure. On the other hand, vibra- tion tests were made at The Church of St. Sergius and Bacchus to analyze the structural characteris- tics and earthquake behavior of the building. Structural modeling of the building, modeled by the Finite Element Method, was outlined by determining its free vibration analysis in compliance with experimental periods. Vertical and earthquake loads of the structure were determined by this model. Keywords: Finite element method, earthquake behavior, church Introduction In this study, The Church of St. Sergius and Bacchus, which was built during 527-536 AD in times of Justinian Regina, is examined. -

Rev. Nicholas Zientarski, Pastor Second, Third, and Fourth Sundays of Each Month at 1PM Rev

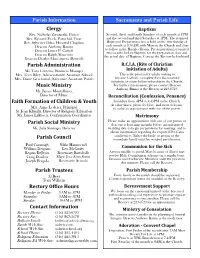

Parish Information Sacraments and Parish Life Clergy Baptism Rev. Nicholas Zientarski, Pastor Second, third, and fourth Sundays of each month at 1PM Rev. Ryszard Ficek, Parochial Vicar and the second and third Saturdays at 1PM. The required Rev. Sylvester Ileka, Hospital Chaplain Baptismal Preparation class is held on the first Sunday of Deacon Anthony Banno each month at 9:30AM, with Mass in the Church and class Deacon James P. Carroll to follow in the Buckley Room. Pre-registration is required two months before Baptism for the preparation class and Deacon Ralph Muscente the actual date of Baptism. Contact the Rectory beforehand. Deacon Charles Muscarnera (Retired) Parish Administration R.C.I.A. (Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults) Ms. Tara Centeno, Business Manager Mrs. Terri Riley, Administrative Assistant, School This is the process for adults wishing to Mrs. Diane Geschwind, Executive Assistant, Parish become Catholic, complete their Sacramental initiation, or attain full membership in the Church. Music Ministry For further information, please contact Deacon Anthony Banno at the Rectory at 223-0723. Mr. James Montalbano, Director of Music Reconciliation (Confession, Penance) Faith Formation of Children & Youth Saturdays from 4PM to 4:45PM in the Church. At other times, please feel free, and most welcome, Mrs. Anne Lederer, Principal to make an appointment with one of the priests. Sr. Joan Klimski, Director of Religious Education Mr. James LaRocca, Confirmation Coordinator Matrimony Parish Social Ministry Please make an appointment with one of our priests or deacons at least nine months before an anticipated Ms. Julia Santiago, Director wedding date to begin preparations for marriage and to obtain information regarding the required Pre-Cana Parish Council conferences. -

And Ninth-Century Rome: the Patrocinia of Diaconiae, Xenodochia, and Greek Monasteries*

FOREIGN SAINTS AT HOME IN EIGHTH- AND NINTH-CENTURY ROME: THE PATROCINIA OF DIACONIAE, XENODOCHIA, AND GREEK MONASTERIES* Maya Maskarinec Rome, by the 9th century, housed well over a hundred churches, oratories, monasteries and other religious establishments.1 A substantial number of these intramural foundations were dedicated to “foreign” saints, that is, saints who were associated, by their liturgical commemoration, with locations outside Rome.2 Many of these foundations were linked to, or promoted by Rome’s immigrant population or travelers. Early medieval Rome continued to be well connected with the wider Mediterranean world; in particular, it boasted a lively Greek-speaking population.3 This paper investigates the correlation between “foreign” institutions and “foreign” cults in early medieval Rome, arguing that the cults of foreign saints served to differentiate these communities, marking them out as distinct units in Rome, while at the same time helping integrate them into Rome’s sacred topography.4 To do so, the paper first presents a brief overview of Rome’s religious institutions associated with eastern influence and foreigners. It * This article is based on research conducted for my doctoral dissertation (in progress) entitled “Building Rome Saint by Saint: Sanctity from Abroad at Home in the City (6th-9th century).” 1 An overview of the existing religious foundations in Rome is provided by the so-called “Catalogue of 807,” which I discuss below. For a recent overview, see Roberto Meneghini, Riccardo Santangeli Valenzani, and Elisabetta Bianchi, Roma nell'altomedioevo: topografia e urbanistica della città dal V al X secolo (Rome: Istituto poligrafico e zecca dello stato, 2004) (hereafter Meneghini, Santangeli Valenzani, and Bianchi, Roma nell'altomedioevo). -

Convocation Exhibitor Catalog

OUR MISSION to bring families closer to Christ in every aspect of life, from baptism, through teen years, to marriage, and beyond. We are the only online course dedicated to one-on-one attention for every couple, every person, to bring the love of Christ to them wherever they may be. www.agapecatholicministries.com THE TANGIBLE FRUITS OF CATHOLICMARRIAGEPREP.COM Responses from a sample of 1,000 engaged couples across the world (2016 numbers) Agapè Catholic Marriage Preparation invites BEFORE BEFORE BEFORE couples to a deeper relationship with each other and with Christ, one couple at a time. 10% 20% IRREGULAR participation in the Online, on-demand instruction rooted in ABSTINENT NO CONTRACEPTION PARISH LIFE Saint John Paul II’s Theology of the Body, combined with personalized mentoring from AFTER AFTER AFTER a trained married couple, builds a foundation for a strong, healthy, Christ-centered 79% 68% 99% marriage between a man and a woman. ABSTINENT NO CONTRACEPTION participation in the www.catholicmarriageprep.com until wedding day PARISH LIFE Building Christ-centered families, one family at a time™ since 2004 An engaging, interactive way for parents and Godparents to The Quinceañera celebrates a girl’s fifteenth birthday, marking prepare together for their infant child/Godchild’s baptism and her passage from childhood to womanhood. Many Catholic the life-long responsibility of passing on their Catholic faith. families request a Mass and a blessing for their daughter. We are here to help in bringing the young lady closer to Christ https://www.agapecatholicministries.com/baptism-prep and to her family. www.catholicquinceprep.com Helping YOU strengthen the vocation of marriage… Diocesan Marriage Summit Parish Marriage Missionaries Fiat Couples Groups …through consultation, training, events and resources for: ü DIOCESES “I highly recommend Annunciation ü PARISHES Ministries to you my brother bishops.” ü MARRIED COUPLES Most Rev.