The Short Stories of Playboy and the Crisis of Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

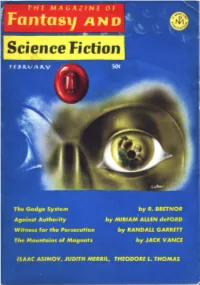

This Month's Issue

FEBRUARY Including Venture Science Fiction NOVELETS Against Authority MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD 20 Witness for the Persecution RANDALL GARRETT 55 The Mountains of Magnatz JACK VANCE 102 SHORT STORIES The Gadge System R. BRETNOR 5 An Afternoon In May RICHARD WINKLER 48 The New Men JOANNA RUSS 75 The Way Back D. K. FINDLAY 83 Girls Will Be Girls DORIS PITKIN BUCK 124 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 19 Books JUDITH MERRIL 41 Desynchronosis THEODORE L. THOMAS 73 Science: Up and Down the Earth ISAAC ASIMOV 91 Editorial 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by George Salter (illustrating "The Gadge System") Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Ed~mrd L. Fcrma11, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. llfil/s, CONSULTING EDITOR The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Volnme 30, No. 2, Wlrolc No. 177, Feb. 1966. Plfblished monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 50¢ a copy. Aunual subscription $5.00; $5.50 in Canada and the Pan American Union, $6.00 in all other cormtries. Publication office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N.H. 03302. Editorial and ge11eral mail sholfld be sent to 3/7 East 53rd St., New York, N. Y. 10022. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N.H. Printed in U.S.A. © 1965 by Mercury Press, Inc. All riglrts inc/fl.ding translations iuto ot/rer la~>guages, resen•cd. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed ent•ciBPes; tire Publisher assumes no responsibility for retlfm of uusolicitcd ma1111scripts. BDITOBIAL The largest volume of mail which crosses our desk each day is that which is classified in the trade as "the slush pile." This blunt term is usually used in preference to the one y11u'll find at the very bottom of our contents page, where it says, ". -

PDF Download the Twilight Zone Radio Dramas, Vol. 18 Lib/E Pdf Free Download

THE TWILIGHT ZONE RADIO DRAMAS, VOL. 18 LIB/E PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Various Authors | none | 01 Sep 2013 | Falcon Picture Group, LLC | 9781482937848 | English | none The Twilight Zone Radio Dramas, Vol. 18 Lib/E PDF Book Based on the teleplay by Rod Serling. Sign In. Overall, a good book for the researcher and enthusiast. He used it and he misused it, and now he's just been handed the bill. Based on a teleplay by Charles Beaumont. Three astronauts return to Earth after seemingly having made an encounter that dooms them and their craft to erasure from existence itself. Recent updates. A henpecked book lover finds himself blissfully alone with his books after a nuclear war. A convict, living alone on an asteroid, receives from the police a realistic woman-robot. Continued from Part One. Constance does grow through the story. You've reached the maximum number of titles you can currently recommend for purchase. Based on an idea by Charles Beaumont and a teleplay by Jerry Sohl. Sue rated it really liked it Mar 21, The first human space colony is about to be rescued from the forsaken planet they've been on for three decades. An impoverished pawnbroker is granted four wishes by a genie in a bottle. The following episodes include stories that were adapted for radio from the original Twilight Zone television scripts, as well as original stories produced exclusively for this radio series. The problem isn't just that his wishes end up not being what he expected--it's what they did end up being. -

George Pal Papers, 1937-1986

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2s2004v6 No online items Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Processed by Arts Library-Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill; Arts Library-Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the George Pal 102 1 Papers, 1937-1986 Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 UCLA Arts Library-Special Collections Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: Art Library-Special Collections staff Date Completed: Unknown Encoded by: D.MacGill © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: George Pal Papers, Date (inclusive): 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 Origination: Pal, George Extent: 36 boxes (16.0 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Shelf location: Held at SRLF. Please contact the Performing Arts Special Collections for paging information. Language: English. Restrictions on Access Advance notice required for access. -

DOUBLE:BILL Symposium

BRIAN W. ALDISS ALLEN KIM LANG POUL ANDERSON KEITH LAUMER PIERS ANTHONY FRITZ LEIBER ISAAC ASIMOV ROBERT A. W. LOWNDES CHARLES BEAUMONT RICHARD LUPOFF GREG BENFORD KATHERINE MacLEAN ALFRED BESTER anne McCaffrey JAMES BLISH J. FRANCIS McCOMAS ROBERT BLOCH DEAN MCLAUGHLIN ANTHONY BOUCHER P. SCHUYLER MILLER LEIGH BRACKETT MICHAEL MOORCOCK RAY BRADBURY LARRY NIVEN MARION ZIMMER BRADLEY ANDRE NORTON REGINALD BRETNOR ALAN E. NOURSE JOHN BRUNNER ANDREW J. OFFUTT KENNETH BULMER ALEXEI PANSHIN ---------------------------------------------- JOHN W. CAMPBELL EMIL PETAJA s JOHN CARNELL H. BEAM PIPER ’ TERRY CARR FREDERIK POHL SYMPOSIUM JOHN CHRISTOPHER ARTHUR PORGES 3r ARTHUR C. CLARKE DANNIE PLACHTA tr HAL CLEMENT MACK REYNOLDS I MARK CLIFTON JOANNA RUSS GROFF CONKLIN ERIC FRANK RUSSELL BASIL DAVENPORT FRED SABERHAGEN AVRAM DAVIDSON JAMES H. SCHMITZ B io HANK DAVIS T. L. SHERRED CHARLES DE VET ROBERT SILVERBERG LESTER DEL REY CLIFFORD D. SIMAK AUGUST DERLETH E. E. 'DOC SMITH PHILIP K. DICK GEORGE 0. SMITH GORDON R. DICKSON JERRY SOHL jllopii HARLAN ELLISON NORMAN SPINRAD PHILIP JOSE FARMER THEODORE STURGEON DANIEL F. GALOUYE JEFF SUTTON DAVID GERROLD WILLIAM F. TEMPLE H. L. GOLD THEODORE L. THOMAS MARTIN GREENBERG WILSON TUCKER JAMES E. GUNN PIERRE VERSINS EDMOND HAMILTON KURT VONNEGUT, JR. double-.bill HARRY HARRISON TED WHITE ZENNA HENDERSON KATE WILHELM JOE HENSLEY ROBERT MOORE WILLIAMS JOHN JAKES JACK WILLIAMSON LEO P. KELLEY RICHARD WILSON DAMON KNIGHT ROBERT F. YOUNG DEAN R. KOONTZ ROGER ZELAZNY $3. the DOUBLE BILL Symposium ...being 94 replies to 'A Questionnaire for Professional Science Fiction Writers and Editors' as Created by: LLOYD BIGGLE, JR. Edited, and Published by: BILL MALLARDI & BILL BOWERS Bill BowersaBill Mallardi press 1969 Portions of this volume appeared in the amateur magazine Double:Bill. -

Download Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories PDF

Download: Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories PDF Free [994.Book] Download Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories PDF By Charles Beaumont Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories you can download free book and read Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories for free here. Do you want to search free download Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories | #87171 in Audible | 2016-01-21 | Format: Unabridged | Original language: English | Running time: 740 minutes | |20 of 22 people found the following review helpful.| Pure Halloween fun. | By G. M. Warnken |The phrase that immediately comes to mind to describe Beaumont is "a poor man's Ray Bradbury", but that's entirely too derogatory for this collection of tales. Beaumont's prose can't equal Bradbury's ecstatic, beautiful collections of metaphors and descriptions—it has a distinctly hard-boiled edge, as though his style was unable to e The profoundly original and wildly entertaining short stories of a legendary Twilight Zone writer. It is only natural that Charles Beaumont would make a name for himself crafting scripts for The Twilight Zone - for his was an imagination so limitless it must have emerged from some other dimension. Perchance to Dream contains a selection of Beaumont's finest stories, including five that he later adapted for Twilight Zone episod [317.Book] Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories PDF [497.Book] Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories By Charles Beaumont Epub [627.Book] Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories By Charles Beaumont Ebook [785.Book] Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories By Charles Beaumont Rar [870.Book] Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories By Charles Beaumont Zip [769.Book] Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories By Charles Beaumont Read Online Free Download: Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories pdf. -

On Waxworks Considered As One of the Hyperreal Arts: Exhibiting Jack the Ripper and His Victims

humanities Article On Waxworks Considered as One of the Hyperreal Arts: Exhibiting Jack the Ripper and His Victims Lucyna Krawczyk-Zywko˙ Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw, 00-681 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] Received: 30 April 2018; Accepted: 24 May 2018; Published: 30 May 2018 Abstract: The article discusses one of the tropes present in the representations of the Whitechapel killer: the waxworks of either the killer or his victims. These images were shaped by contemporary attitudes: from sensationalism in 1888, through the developing myth and business of ‘Jack the Ripper,’ to the beginnings of attention being paid to his victims. Examined are tableaus created from 1888 to current times, both physical and fictional twenty- and twenty-first-century texts encompassing various media, all of which may be located within the Baudrillardian realm of simulation. What they demonstrate is that the mythical killer keeps overshadowing his victims, who in this part of the Ripper mythos remain to a certain extent as dehumanised and voiceless as when they were actually killed. Keywords: Jack the Ripper; representation; simulacrum; victims; waxworks Waxworks was one of the manifestations of the nineteenth-century fascination with the nascent cult and culture of celebrities, a culture that in the twentieth century incorporated serial killers as well (Schmid 2006). In the nineteenth century, visiting exhibitions of wax figures which included infamous criminals was a means of substituting for the ‘lost pleasure’ of public hangings (Pamela Pilbeam qtd. in Worsley [2013] 2014, p. 58). The association of representations of villains with this medium became so close that its dictionary definition includes the following usage as an example: “no waxworks is complete without its chamber of horrors” (Waxwork n.dat.). -

Season4article.Pdf

N.B.: IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE TWO-PAGE VIEW IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. VIEW/PAGE DISPLAY/TWO-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT) and ENABLE SCROLLING “EVENING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” (minus ‘The’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019 The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Author permissions are required to reprint all or part of this work. www.twilightzonemuseum.com * www.facebook.com/twilightzonemuseum Preface At this late date, little has not been said about The Twilight Zone. It’s often imitated, appropriated, used – but never remotely matched. From its quiet and decisively non-ostentatious beginnings, it steadily grew into its status as an icon and televisional gemstone…and not only changed the way we looked at the world but became an integral part of it. But this isn’t to say that the talk of it has been evenly distributed. Certain elements, and full episodes, of the Rod Serling TV show get much more attention than others. Various characters, plot elements, even plot devices are well-known to many. But I dare say that there’s a good amount of the series that remains unknown to the masses. In particular, there has been very much less talk, and even lesser scholarly treatment, of the second half of the series. This “study” is two decades in the making. It started from a simple episode guide, which still exists. Out of it came this work. The timing is right. In 2019, the series turns sixty years old. -

Playboy 1962

THE BLOODY PULPS nostalgia By CHARLES BEAUMONT in the days of our youth they were not deemed good reading and to us at the time they weren’t good, they were great PLAYBOY, September 1962 2 THERE WAS A RITUAL. potent literary drug known to boy, and all of us It was dark and mysterious, as rituals ought to suffer withdrawal symptoms to this day. No one be, and—for those who enacted it—a holy and ever kicked the pulps cold turkey. They were too enchanted thing. powerful an influence. Instead, most of us tried to If you were a prepubescent American male in the ease off. Having dreamed of owning complete sets, Twenties, the Thirties or the Forties, chances are in mint condition, of all the pulp titles ever you performed the ritual. If you were a little too published, and having realized perhaps a tenth part tall, a little too short, a little too fat, skinny, pimply, of the dream—say, 1500 magazines, or a an only child, painfully shy, awkward, scared of bedroomful—we suffered that vague disen- girls, terrified of bullies, poor at your schoolwork chantment that is the first sign of approaching (not because you weren’t bright but because you maturity (16, going on 17, was usually when it wouldn’t apply yourself), uncomfortable in large happened) and decided to be sensible. Accordingly, crowds, given to brooding, and totally and we stopped buying all the new mags as fast as they overwhelmingly convinced of your personal could appear, and concentrated instead upon a few inadequacy in any situation, then you certainly indispensable items. -

Panel About Harlan Ellison

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Nat Segaloff and Tim Richmond, July 2019 Nat Segaloff is a writer, broadcaster, teacher, film historian, and raconteur with a varied background in motion picture publicity, journalism, and producing. He is the author of A Lit Fuse: The Provocative Life of Harlan Ellison https://www.nesfa.org/book/a-lit-fuse/ Tim Richmond wrote the authorized bibliography of Ellison's work, "Fingerprints on the Sky." It was the product of 20 years of research and chronicles the entire canon of Ellison’s work over nearly seven decades and across all mediums. Gary Denton: What is the best explanation to what happened to ‘The Last Dangerous Visions”? Nat Segaloff: Tim has a more detailed answer but, in my opinion, Harlan got involved in other projects with tighter deadlines. He also, I suspect, was intimidated by the expectation of people who bought the Dangerous Visions® books not only for the stories but for his remarkable introductions. Those took time and energy and, moreover, demanded a chunk of his emotional energy. There is a difference between writing fiction (which Harlan could do efficiently) and writing literary analysis, which is what the Dangerous Visions® books demand. Tim Richmond: The tome that is LDV sits in a filing cabinet unfinished. There are a number of reasons for this which I will try to explain although it is/was a touchy subject for Harlan. For starts he really wasn't keen on doing it from the outset. The process that he had established was arduous and took away from other writing projects. -

(March 2019) William F. Nolan Writes Mostly in the Science Fiction, Fa

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with William F. Nolan (March 2019) William F. Nolan writes mostly in the science fiction, fantasy, and horror genres. Though best known for co-authoring the classic dystopian science fiction novel Logan’s Run with George Clayton Johnson, Nolan is the author of more than 2000 pieces (fiction, nonfiction, articles and books), and has edited 26 anthologies in his 50+ year career. An artist, Nolan was born in Kansas City, Missouri, and worked at Hallmark Cards, Inc. and in comic books before becoming an author. In the 1950s, Nolan was an integral part of the writing ensemble known as “The Group,” which included many well-known genre writers, such as Ray Bradbury, Charles Beaumont, John Tomerlin, Richard Matheson, Johnson and others, many of whom wrote for Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone. Nolan is considered a leading expert on Dashiell Hammett, pulps such as Black Mask and Western Story, and is the world authority on the works of prolific scribe Max Brand. Of his numerous awards, there are a few of which he is most proud: being voted a Living Legend in Dark Fantasy by the International Horror Guild in 2002; twice winning the Edgar Allan Poe Award from the Mystery Writers of America; being awarded the honorary title of Author Emeritus by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Inc. in 2006, and receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Horror Writers Association in 2010. Adam J. Meek: Were you happy with the Logan's Run film? William F. Nolan: Yes and no. -

SFRA Newsletter Puhlished Ten Times a Year Hy the Science Fiction Research Associa Tion

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 11-1-1988 SFRA ewN sletter 162 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 162 " (1988). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 107. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/107 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The SFRA Newsletter Puhlished ten times a year hy The Science Fiction Research Associa tion. Copyright ~ 1988 by the SFRA. Address editorial correspon dence to SFRA Newsletter, English Dept., Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431. Editor: Robert A. Collins; Associate Editor: Catherine Fischer; Rel'iell' Editor: Rob Latham; Film Editor: Ted Krulik; Book News Editor: Martin A. Schneider; EditOlial Assistallt: Jeanette Lawson. Send changes of address to the Secretary, enquiries concerning subscriptions to the Treasurer, listed below. Past Presidents of SFRA Thomas D. Clareson (1970-76) SFRA Executive Arthur O. Lewis, Jr. (1977-78) Committee Joe De Bolt (1979-80) James Gunn (1981-82) Patricia S. Warrick (1983-84) Donald M. Hassler (1985-86) President William H. Hardesty, III Past Editors of the Newsletter English Department Fred Lerner (1971-74) Miami University Beverly Friend (1974-78) Oxford, OH 45056 Roald Tweet (1978-81) Elizabeth Anne Hull (1981-84) Vice-President Richard W.