(March 2019) William F. Nolan Writes Mostly in the Science Fiction, Fa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K. A. Applegate Jeffrey Archer Diana Athill Paul Auster Wasi Ahmed Victoria Aveyard Kevin Baker Mark Allen Baker Nicholson Baker Iain Banks Russell Banks Julian Barnes Andrea Barrett Max Barry Sebastian Barry Louis Bayard Peter Behrens Elizabeth Berg Wendell Berry Maeve Binchy Dustin Lance Black Holly Black Amy Bloom Chris Bohjalian Roberto Bolano S. J. Bolton William Boyd T. C. Boyle John Boyne Paula Brackston Adam Braver Libba Bray Alan Brennert Andre Brink Max Brooks Dan Brown Don Brown www.downloadexcelfiles.com Christopher Buckley John Burdett James Lee Burke Augusten Burroughs A. S. Byatt Bhalchandra Nemade Peter Cameron W. Bruce Cameron Jacqueline Carey Peter Carey Ron Carlson Stephen L. Carter Eleanor Catton Michael Chabon Diane Chamberlain Jung Chang Kate Christensen Dan Chaon Kelly Cherry Tracy Chevalier Noam Chomsky Tom Clancy Cassandra Clare Susanna Clarke Chris Cleave Ernest Cline Harlan Coben Paulo Coelho J. M. Coetzee Eoin Colfer Suzanne Collins Michael Connelly Pat Conroy Claire Cook Bernard Cornwell Douglas Coupland Michael Cox Jim Crace Michael Crichton Justin Cronin John Crowley Clive Cussler Fred D'Aguiar www.downloadexcelfiles.com Sandra Dallas Edwidge Danticat Kathryn Davis Richard Dawkins Jonathan Dee Frank Delaney Charles de Lint Tatiana de Rosnay Kiran Desai Pete Dexter Anita Diamant Junot Diaz Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni E. L. Doctorow Ivan Doig Stephen R. Donaldson Sara Donati Jennifer Donnelly Emma Donoghue Keith Donohue Roddy Doyle Margaret Drabble Dinesh D'Souza John Dufresne Sarah Dunant Helen Dunmore Mark Dunn James Dashner Elisabetta Dami Jennifer Egan Dave Eggers Tan Twan Eng Louise Erdrich Eugene Dubois Diana Evans Percival Everett J. -

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of Fc Available for $4.00 From: TRISKELL PRESS P

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of fc Available for $4.00 from: TRISKELL PRESS P. 0. Box 9480 Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1G 3V2 J&u) (B.Mn'^mTuer KOKTAL ADD IHHOHTAl LOVERS TRAPPED Is AS ASCIEST FEUD... 11th ANNUAL FANTASY FAIRS JULY 17, 18, 19, 1981 AMFAC HOTEL MASTERS OF CEREMONIES STEPHEN GOLDIN, KATHLEEN SKY RON WILSON CONTENTS page GUEST OF HONOR ... 4 ■ GUEST LIST . 5 WELCOME TO FANTASY FAIRE by’Keith Williams’ 7 PROGRAM 8 COMMITTEE...................... .. W . ... .10 RULES FOR BEHAVIOR 10 WALKING GUIDE by Bill Conlln 12 MAP OF AREA ........................................................ UPCOMING FPCI CONVENTIONS 14 ADVERTISERS Triskell Press Barry Levin Books Pfeiffer's Books & Tiques Dangerous Visions Cover Design From A Painting By Morris Scott Dollens GUEST OF HONOR FRITZ LEIBER was bom in 1910. Son of a Shakespearean actor, Fritz was at one time an actor himself and a mem ber of his father’s troupe. He made a cameo appearance in the film "Equinox." Fritz has studied many sciences and was once editor of Science Digest. His writing career began prior to World War 11 with some stories in Weird Tales. Soon Unknown published his novel "Conjure Wife, " which was made into a movie under the title (of all things) "Bum, Witch, Bum!" His Gray Mouser stories (which were the inspira tion for the Fantasy Faire "Fritz Leiber Fantasy Award") were started in Unknown and continued in Fantastic, which magazine devoted its entire Nov., 1959 issue to Fritz's stories. In 1959 Fritz was awarded a Hugo, by the World Science Fiction Convention for his novel "The Big Time." His novel "The Wanderer," about an interloper into our solar system, won the Hugo again in 1965.'-His novelettes Gonna Roll the Bones," "Ship of Shadows" and "Ill Met in Lankhmar” won the Hugo in 1968, 1970 and 1971 in that order. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Argentuscon Had Four Panelists Piece, on December 17

Matthew Appleton Georges Dodds Richard Horton Sheryl Birkhead Howard Andrew Jones Brad Foster Fred Lerner Deb Kosiba James D. Nicoll Rotsler John O’Neill Taral Wayne Mike Resnick Peter Sands Steven H Silver Allen Steele Michael D. Thomas Fred Lerner takes us on a literary journey to Portugal, From the Mine as he prepared for his own journey to the old Roman province of Lusitania. He looks at the writing of two ast year’s issue was published on Christmas Eve. Portuguese authors who are practically unknown to the This year, it looks like I’ll get it out earlier, but not Anglophonic world. L by much since I’m writing this, which is the last And just as the ArgentusCon had four panelists piece, on December 17. discussing a single topic, the first four articles are also on What isn’t in this issue is the mock section. It has the same topic, although the authors tackled them always been the most difficult section to put together and separately (mostly). I asked Rich Horton, John O’Neill, I just couldn’t get enough pieces to Georges Dodds, and Howard Andrew Jones make it happen this issue. All my to compile of list of ten books each that are fault, not the fault of those who sent out of print and should be brought back into me submissions. The mock section print. When I asked, knowing something of may return in the 2008 issue, or it may their proclivities, I had a feeling I’d know not. I have found something else I what types of books would show up, if not think might be its replacement, which the specifics. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

RAMSEY CAMPBELL INTERVIEWED RAMSEY CAMPBELL INTERVIEW ^By Brendan Ryder Page 13

ISSUE NO. 76 August 1992 ________ ISSN 0791-3966 RAMSEY CAMPBELL INTERVIEWED RAMSEY CAMPBELL INTERVIEW ^by Brendan Ryder page 13 THE TWILIGHT ZONE How to find your way around by Michael Cullen page 5 OUR SEMI-ANNUAL "MEGA" QUIZ It’s not just a quiz, it's the contents of page 11 MORPHING So how did Arnie turn into Michael Jackson? See on page 12 REGULAR FEATURES News 3 ISFA News 4 Letters 7 Meeting report 8 Movies 9 Videos 10 Book Reviews 15 Comics 18 Drabbles 19 PUBLISHED BY Wc welcome unsolicited manuscripts on the basis that the THE IRISH SCIENCE FICTION ISFA is poor, and if wc don’t actually pay contributors it ASSOCIATION doesn’t mean wc don’t appreciate them. So send us your news. Send us your opinions. Send us your doodles. Send 30, BEVERLY DOWNS us your shorts. But wash ’em first. KNOCKLYON ROAD Take that old dusty Royal out of the wardrobe and type it, TEMPLEOGUE, DUBLIN 16 if you can. If you can’t, well, it’s not the end of the world. FURTHER INFORMATION NOTE: OPINIONS EXPRESSED ARE NOT THOSE OF FROM THIS ADDRESS OR THE ISFA, EXCEPT WHERE STATED AS SUCH PHONE 934712 2 ISFA Newsletter August 1992 NEWS Crypt Creator Dies Wiliam M Gaines, publisher of Mad maga zine and the EC comics line which included Rings, No Strings Weird Science, Tales from the Crypt, and As part of the Galway Arts Festival which ran The Vault of Horror, died in Manhattan in from 15-26 July, the Canadian Theatre Sans June, at the age of 70. -

The Short Stories of Playboy and the Crisis of Masculinity

The Short Stories of Playboy and the Crisis of Masculinity Men in Playboy’s Short Fiction and 1950s America Pieter-Willem Verschuren [3214117] [Supervisor: prof. dr. J. van Eijnatten] 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 State of the Art .................................................................................................................................... 4 History: Male Anxieties in the 1950s ............................................................................................... 5 Male Identity ................................................................................................................................... 7 Magazines ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Playboy ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Theoretical Framework ....................................................................................................................... 9 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Masculinity .................................................................................................................................... 12 Identity ......................................................................................................................................... -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

This Month's Issue

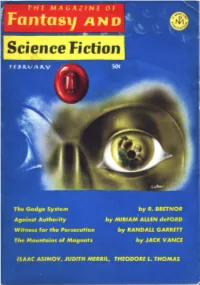

FEBRUARY Including Venture Science Fiction NOVELETS Against Authority MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD 20 Witness for the Persecution RANDALL GARRETT 55 The Mountains of Magnatz JACK VANCE 102 SHORT STORIES The Gadge System R. BRETNOR 5 An Afternoon In May RICHARD WINKLER 48 The New Men JOANNA RUSS 75 The Way Back D. K. FINDLAY 83 Girls Will Be Girls DORIS PITKIN BUCK 124 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 19 Books JUDITH MERRIL 41 Desynchronosis THEODORE L. THOMAS 73 Science: Up and Down the Earth ISAAC ASIMOV 91 Editorial 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by George Salter (illustrating "The Gadge System") Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Ed~mrd L. Fcrma11, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. llfil/s, CONSULTING EDITOR The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Volnme 30, No. 2, Wlrolc No. 177, Feb. 1966. Plfblished monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 50¢ a copy. Aunual subscription $5.00; $5.50 in Canada and the Pan American Union, $6.00 in all other cormtries. Publication office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N.H. 03302. Editorial and ge11eral mail sholfld be sent to 3/7 East 53rd St., New York, N. Y. 10022. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N.H. Printed in U.S.A. © 1965 by Mercury Press, Inc. All riglrts inc/fl.ding translations iuto ot/rer la~>guages, resen•cd. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed ent•ciBPes; tire Publisher assumes no responsibility for retlfm of uusolicitcd ma1111scripts. BDITOBIAL The largest volume of mail which crosses our desk each day is that which is classified in the trade as "the slush pile." This blunt term is usually used in preference to the one y11u'll find at the very bottom of our contents page, where it says, ". -

Musings from My “Haunted” Hermitage DON't TOUCH THAT DIAL!

Musings from my “haunted” Hermitage by Larry F. Ginsberg DON’T TOUCH THAT DIAL! “Maybe all the schemes of the devil were nothing compared to what man could think up.” Joe Hill Who can ever forget those opuses of Horror from the literary masters of the Macabre, Lovecraft’s The Dunwich Horror, Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher, Bran Stroker’s Dracula, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, Robert Lewis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, amongst many others. Do you remember cringing, shaking and shrieking during those weekend Matinees, watching The Mummy and The Werewolf, Dracula and Frankenstein, Friday the Thirteenth and Halloween. We were riveted in our seats with fear and suspense by Lon Chaney, Sr. and Jr., Vincent Price, and Boris Karloff. But, are you aware that the King of Television Horror was a Jewish producer born and raised in Bridgeport? Meet Dan Curtis born Daniel Mayer Cherkoss (August 12, 1927 – March 27, 2006), Producer, Director and Writer of man- made schemes of the Devil. In the Dead of the Night, Intruders and The Night Stalker brought Burnt Offerings to the House of Dark Shadows. The Curse of the Black Widow, The Scream of the Wolf and The Turn of the Screw formed a Trilogy of Terror. Who can ever forget the Vampire Barnabas Collins, the Zuni Fetish Doll, the Haunted Allardyce family home and The Norliss Tapes’ eerie occult investigations! Curtis frequently collaborated with sci-fi/horror writers Richard Matheson and William F. -

Nominations�1

Section of the WSFS Constitution says The complete numerical vote totals including all preliminary tallies for rst second places shall b e made public by the Worldcon Committee within ninety days after the Worldcon During the same p erio d the nomination voting totals shall also b e published including in each category the vote counts for at least the fteen highest votegetters and any other candidate receiving a numb er of votes equal to at least ve p ercent of the nomination ballots cast in that category The Hugo Administrator reports There were valid nominating ballots and invalid nominating ballots There were nal ballots received of which were valid Most of the invalid nal ballots were electronic ballots with errors in voting which were corrected by later resubmission by the memb ers only the last received ballot for each memb er was counted Best Novel 382 nominating ballots cast 65 Brasyl by Ian McDonald 58 The Yiddish Policemens Union by Michael Chab on 58 Rol lback by Rob ert J Sawyer 41 The Last Colony by John Scalzi 40 Halting State by Charles Stross 30 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal lows by J K Rowling 29 Making Money by Terry Pratchett 29 Axis by Rob ert Charles Wilson 26 Queen of Candesce Book Two of Virga by Karl Schro eder 25 Accidental Time Machine by Jo e Haldeman 25 Mainspring by Jay Lake 25 Hapenny by Jo Walton 21 Ragamun by Tobias Buckell 20 The Prefect by Alastair Reynolds 19 The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss Best Novella 220 nominating ballots cast 52 Memorare by Gene Wolfe 50 Recovering Ap ollo