Ray Bradbury on Screen: Martians, Beasts and Burning Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of Fc Available for $4.00 From: TRISKELL PRESS P

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of fc Available for $4.00 from: TRISKELL PRESS P. 0. Box 9480 Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1G 3V2 J&u) (B.Mn'^mTuer KOKTAL ADD IHHOHTAl LOVERS TRAPPED Is AS ASCIEST FEUD... 11th ANNUAL FANTASY FAIRS JULY 17, 18, 19, 1981 AMFAC HOTEL MASTERS OF CEREMONIES STEPHEN GOLDIN, KATHLEEN SKY RON WILSON CONTENTS page GUEST OF HONOR ... 4 ■ GUEST LIST . 5 WELCOME TO FANTASY FAIRE by’Keith Williams’ 7 PROGRAM 8 COMMITTEE...................... .. W . ... .10 RULES FOR BEHAVIOR 10 WALKING GUIDE by Bill Conlln 12 MAP OF AREA ........................................................ UPCOMING FPCI CONVENTIONS 14 ADVERTISERS Triskell Press Barry Levin Books Pfeiffer's Books & Tiques Dangerous Visions Cover Design From A Painting By Morris Scott Dollens GUEST OF HONOR FRITZ LEIBER was bom in 1910. Son of a Shakespearean actor, Fritz was at one time an actor himself and a mem ber of his father’s troupe. He made a cameo appearance in the film "Equinox." Fritz has studied many sciences and was once editor of Science Digest. His writing career began prior to World War 11 with some stories in Weird Tales. Soon Unknown published his novel "Conjure Wife, " which was made into a movie under the title (of all things) "Bum, Witch, Bum!" His Gray Mouser stories (which were the inspira tion for the Fantasy Faire "Fritz Leiber Fantasy Award") were started in Unknown and continued in Fantastic, which magazine devoted its entire Nov., 1959 issue to Fritz's stories. In 1959 Fritz was awarded a Hugo, by the World Science Fiction Convention for his novel "The Big Time." His novel "The Wanderer," about an interloper into our solar system, won the Hugo again in 1965.'-His novelettes Gonna Roll the Bones," "Ship of Shadows" and "Ill Met in Lankhmar” won the Hugo in 1968, 1970 and 1971 in that order. -

Questions to Accompany the Martian Chronicles

Questions to Accompany The Martian Chronicles Essential Questions: • What are the causes and effects of political turmoil in the novel The Martian Chronicles? • How do the main characters in the text and people in general make decisions based on both their political and ethical beliefs? • How do the conflicts in the texts mirror historical and modern political events? Guiding Questions: • Pay careful attention to “Rocket Summer”. What is the significance of the chapter and what is Bradbury’s intention by beginning the novel with that story? • Note the different reactions of Mr. K & Mrs. K to the newcomers. How do their decisions reflect their personalities and how do their personalities affect their decisions? At some point come back and decide whose action was correct—does it matter what their individual motives were? • Examine the Martian culture—how is it like human culture and how is it different? What can you determine the Martians value by looking at their attitudes, art, architecture, recreation, etc. What social commentary is Bradbury revealing here? • The 2nd expedition to Mars is also a failure. What do we as readers learn about humans and Martians from this chapter? What do we learn about our current society from this chapter? • The 3rd expedition fails as well. What does this chapter (along with the 2nd expedition) say about beliefs and logical reasoning? What are you more likely to believe, what you see to be true, what you think to be true, or what you know to be true? When do you change your mind? • In what way does the 4th expedition resemble the historical accounts of European explorers coming to the new world? Based on your understanding of historical events, do you think Spender’s actions are understandable? • Who do you blame for the Martians’’ fate? What were the choices that led to this outcome? Was there another way? • The settlers are coming. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Argentuscon Had Four Panelists Piece, on December 17

Matthew Appleton Georges Dodds Richard Horton Sheryl Birkhead Howard Andrew Jones Brad Foster Fred Lerner Deb Kosiba James D. Nicoll Rotsler John O’Neill Taral Wayne Mike Resnick Peter Sands Steven H Silver Allen Steele Michael D. Thomas Fred Lerner takes us on a literary journey to Portugal, From the Mine as he prepared for his own journey to the old Roman province of Lusitania. He looks at the writing of two ast year’s issue was published on Christmas Eve. Portuguese authors who are practically unknown to the This year, it looks like I’ll get it out earlier, but not Anglophonic world. L by much since I’m writing this, which is the last And just as the ArgentusCon had four panelists piece, on December 17. discussing a single topic, the first four articles are also on What isn’t in this issue is the mock section. It has the same topic, although the authors tackled them always been the most difficult section to put together and separately (mostly). I asked Rich Horton, John O’Neill, I just couldn’t get enough pieces to Georges Dodds, and Howard Andrew Jones make it happen this issue. All my to compile of list of ten books each that are fault, not the fault of those who sent out of print and should be brought back into me submissions. The mock section print. When I asked, knowing something of may return in the 2008 issue, or it may their proclivities, I had a feeling I’d know not. I have found something else I what types of books would show up, if not think might be its replacement, which the specifics. -

It Came from Outer Space: the Virus, Cultural Anxiety, and Speculative

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 It came from outer space: the virus, cultural anxiety, and speculative fiction Anne-Marie Thomas Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Thomas, Anne-Marie, "It came from outer space: the virus, cultural anxiety, and speculative fiction" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4085. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4085 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. IT CAME FROM OUTER SPACE: THE VIRUS, CULTURAL ANXIETY, AND SPECULATIVE FICTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Anne-Marie Thomas B.A., Texas A&M-Commerce, 1994 M.A., University of Arkansas, 1997 August 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract . iii Chapter One The Replication of the Virus: From Biomedical Sciences to Popular Culture . 1 Two “You Dropped A Bomb on Me, Baby”: The Virus in Action . 29 Three Extreme Possibilities . 83 Four To Devour and Transform: Viral Metaphors in Science Fiction by Women . 113 Five The Body Electr(on)ic Catches Cold: Viruses and Computers . 148 Six Coda: Viral Futures . -

THE INNOCENTS Directed by Jack Clayton UKUS, 1961, 100 Mins, Cert 12A

THE INNOCENTS Directed by Jack Clayton UKUS, 1961, 100 mins, Cert 12A Starring Deborah Kerr, Peter Wyngarde, Michael Redgrave Martin Stephens, Pamela Franklin Opening on 13 December 2013 at BFI Southbank, IFI Dublin, QFT Belfast & selected cinemas nationwide 24 October 2013 – The second of three films to be released by the BFI in cinemas nationwide as part of GOTHIC: The DarK Heart of Film is Jack Clayton’s 1961 feature The Innocents, now widely considered to be one of the greatest of all cinematic tales of terror. This celebrated adaptation of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (1898) was scripted by William Archibald (whose play of the book had been on Broadway) and Truman Capote, with additional scenes and dialogue by John Mortimer. A brilliant exercise in psychological horror, The Innocents tells of an impressionable and repressed governess, Miss Giddens (Deborah Kerr), who agrees to tutor two orphaned children, Miles (Martin Stephens) and Flora (Pamela Franklin). On arrival at Bly House, she becomes convinced that the children are possessed by the perverse spirits of former governess Miss Jessel (Clytie Jessop) and her Heathclifflike lover Quint (Peter Wyngarde), who both met with mysterious deaths. The sinister atmosphere of The Innocents is carefully created – not through shocK tactics – but through its cinematography, soundtrack, and decor: Freddie Francis’ beautiful CinemaScope photography, with its eerily indistinct long shots and mysterious manifestations at the edges of the frame; Georges Auric’s eVocative and spooky soundtrack; and the grand yet decaying Bly House, with spiders crawling from dilapidated statues, ants from the eyes of dolls, and rooms coVered in dust sheets. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

The Short Stories of Playboy and the Crisis of Masculinity

The Short Stories of Playboy and the Crisis of Masculinity Men in Playboy’s Short Fiction and 1950s America Pieter-Willem Verschuren [3214117] [Supervisor: prof. dr. J. van Eijnatten] 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 State of the Art .................................................................................................................................... 4 History: Male Anxieties in the 1950s ............................................................................................... 5 Male Identity ................................................................................................................................... 7 Magazines ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Playboy ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Theoretical Framework ....................................................................................................................... 9 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Masculinity .................................................................................................................................... 12 Identity ......................................................................................................................................... -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

This Month's Issue

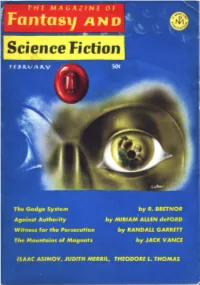

FEBRUARY Including Venture Science Fiction NOVELETS Against Authority MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD 20 Witness for the Persecution RANDALL GARRETT 55 The Mountains of Magnatz JACK VANCE 102 SHORT STORIES The Gadge System R. BRETNOR 5 An Afternoon In May RICHARD WINKLER 48 The New Men JOANNA RUSS 75 The Way Back D. K. FINDLAY 83 Girls Will Be Girls DORIS PITKIN BUCK 124 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 19 Books JUDITH MERRIL 41 Desynchronosis THEODORE L. THOMAS 73 Science: Up and Down the Earth ISAAC ASIMOV 91 Editorial 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by George Salter (illustrating "The Gadge System") Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Ed~mrd L. Fcrma11, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. llfil/s, CONSULTING EDITOR The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Volnme 30, No. 2, Wlrolc No. 177, Feb. 1966. Plfblished monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 50¢ a copy. Aunual subscription $5.00; $5.50 in Canada and the Pan American Union, $6.00 in all other cormtries. Publication office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N.H. 03302. Editorial and ge11eral mail sholfld be sent to 3/7 East 53rd St., New York, N. Y. 10022. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N.H. Printed in U.S.A. © 1965 by Mercury Press, Inc. All riglrts inc/fl.ding translations iuto ot/rer la~>guages, resen•cd. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed ent•ciBPes; tire Publisher assumes no responsibility for retlfm of uusolicitcd ma1111scripts. BDITOBIAL The largest volume of mail which crosses our desk each day is that which is classified in the trade as "the slush pile." This blunt term is usually used in preference to the one y11u'll find at the very bottom of our contents page, where it says, ". -

Working Materials

PROJECT No - 2016-1-HR01-KA201-022159 Handbook for reluctant, struggling and poor readers http://www.angelfire.com/or/grace/marionettes.html Marionettes, Inc. By Ray Bradbury, from "The Illustrated Man" Beginning of the 1st excerpt They walked slowly down the street at about ten in the evening, talking calmly. They were both about thirty-five, both eminently sober. "But why so early?" said Smith. "Because," said Braling. "Your first night out in years and you go home at ten o'clock." "Nerves, I suppose." "What I wonder is how you ever managed it. I've been trying to get you out for ten years for a quiet drink. And now, on the one night, you insist on turning in early." "Musn't crowd my luck," said Braling. "What did you do, put sleeping powder in your wife's coffee?" "No, that would be unethical. You'll see soon enough." They turned a corner. "Honestly, Braling, I hate to say this, but you HAVE been patient with her. You may not admit it to me, but marriage has been awful for you, hasn't it?" "I wouldn't say that." "It's got around, anyway, here and there, how she got you to marry her. That time back in 1979 when you were going to Rio-----" "Dear Rio. I never DID see it after all my plans." "And how she tore her clothes and rumpled her hair and threatened to call the police unless you married her." September, 2017 Training materials for 1 “Marionettes, Inc.” PROJECT No - 2016-1-HR01-KA201-022159 Handbook for reluctant, struggling and poor readers "She was always nervous, Smith, understand." "It was more than unfair.