Charles Beaumont: an Appreciation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Short Stories of Playboy and the Crisis of Masculinity

The Short Stories of Playboy and the Crisis of Masculinity Men in Playboy’s Short Fiction and 1950s America Pieter-Willem Verschuren [3214117] [Supervisor: prof. dr. J. van Eijnatten] 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 State of the Art .................................................................................................................................... 4 History: Male Anxieties in the 1950s ............................................................................................... 5 Male Identity ................................................................................................................................... 7 Magazines ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Playboy ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Theoretical Framework ....................................................................................................................... 9 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Masculinity .................................................................................................................................... 12 Identity ......................................................................................................................................... -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories Ebook

PERCHANCE TO DREAM: SELECTED STORIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles Beaumont | 304 pages | 05 May 2016 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780143107651 | English | London, United Kingdom Perchance to Dream: Selected Stories PDF Book Mag lay still; almost, it seemed to Austin, expectant, waiting. Supernatural, horror, noir, science fiction, fantasy, pulp, and more: all were equally at home in his wondrous mind. The little leather bags of hex-magic: nail-filings, photographs, specks of flesh; the rubbing boards stained with fruit- skins; the piles of bones at the feet of the men—old bones, very brittle and dry and old. If you do not sweat blood by the pint or the jeroboam, if you do not think loud and long or silent and heavy, and show traces of the sunken pit and the glorious masochism of the litterateur on your faces, you, sir, you, madam, are not a writer. It all looked, now, like the model he had presented to the Senators. I admired and envied him while he lived, and suffered his absence when he moved away into illness and death. Magic can get beautiful women to have sex with you, and this is a harmless and wacky high-jink despite how unwilling said women were beforehand and how chillingly methodical you are about spiking their drinks. Examples of this hybrid tale here are "The Jungle" transformed considerably into a "TZ" episode seven years later , where the builder of a futuristic city in the wilds of Kenya is terrorized by the local natives; "Fritzchen," a truly bizarre and bizarrely written tale of a very strange pet; and "Place of Meeting," where we find the last residents of a devastated Earth, and learn something of their macabre background. -

This Month's Issue

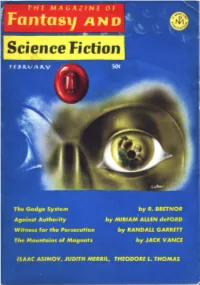

FEBRUARY Including Venture Science Fiction NOVELETS Against Authority MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD 20 Witness for the Persecution RANDALL GARRETT 55 The Mountains of Magnatz JACK VANCE 102 SHORT STORIES The Gadge System R. BRETNOR 5 An Afternoon In May RICHARD WINKLER 48 The New Men JOANNA RUSS 75 The Way Back D. K. FINDLAY 83 Girls Will Be Girls DORIS PITKIN BUCK 124 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 19 Books JUDITH MERRIL 41 Desynchronosis THEODORE L. THOMAS 73 Science: Up and Down the Earth ISAAC ASIMOV 91 Editorial 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by George Salter (illustrating "The Gadge System") Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Ed~mrd L. Fcrma11, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. llfil/s, CONSULTING EDITOR The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Volnme 30, No. 2, Wlrolc No. 177, Feb. 1966. Plfblished monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 50¢ a copy. Aunual subscription $5.00; $5.50 in Canada and the Pan American Union, $6.00 in all other cormtries. Publication office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N.H. 03302. Editorial and ge11eral mail sholfld be sent to 3/7 East 53rd St., New York, N. Y. 10022. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N.H. Printed in U.S.A. © 1965 by Mercury Press, Inc. All riglrts inc/fl.ding translations iuto ot/rer la~>guages, resen•cd. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed ent•ciBPes; tire Publisher assumes no responsibility for retlfm of uusolicitcd ma1111scripts. BDITOBIAL The largest volume of mail which crosses our desk each day is that which is classified in the trade as "the slush pile." This blunt term is usually used in preference to the one y11u'll find at the very bottom of our contents page, where it says, ". -

DUBLIN GHOST STORY FESTIVAL Friday, 29 June – Sunday, 1 July 2018 Grand Lodge of Ireland, 17 Molesworth Street

DUBLIN GHOST STORY FESTIVAL 2018 é F ile 2018 é í Sc alta Taibhs Á Bhaile tha Cliath DUBLIN GHOST STORY FESTIVAL Friday, 29 June – Sunday, 1 July 2018 Grand Lodge of Ireland, 17 Molesworth Street Guest of Honour JOYCE CAROL OATES Joyce Carol Oates’s career spans half a century and with nearly fifty novels to her name. She is the recipient of multiple awards including the National Book Award, the O. Henry Award, the National Humanities Medal, the PEN America Lifetime Achievement Award, as well as multiple nominations for the Pulitzer Prize. Oates’s interest in supernatural literature is well-known. She has edited a volume of Shirley Jackson’s work for the Library of America, a selection of American gothic tales for Penguin, and written extensively on H.P. Lovecraft. Oates has also penned multiple volumes of her own supernatural and macabre stories, including Night-Side (1977), Haunted: Tales of the Grotesque (1994), the Stoker Award-winning collection The Corn Maiden and Other Nightmares (2011), The Doll-Master and Other Tales of Terror (2016), and Night-Gaunts and Other Tales of Suspense (2018). OUR ESTEEMED GUESTS HELEN GRANT Helen Grant is best known for her Young Adult thrillers, including the award- winning The Vanishing of Katharina Linden . She also writes ghost stories, a collection of which was published under the title The Sea Change & Other Stories in 2013. Helen is a lifelong fan of M. R. James and has often written about him for the M. R. James Ghosts and Scholars Newsletter . She has a particular interest in his foreign locations, most of which she has visited. -

PDF Download the Twilight Zone Radio Dramas, Vol. 18 Lib/E Pdf Free Download

THE TWILIGHT ZONE RADIO DRAMAS, VOL. 18 LIB/E PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Various Authors | none | 01 Sep 2013 | Falcon Picture Group, LLC | 9781482937848 | English | none The Twilight Zone Radio Dramas, Vol. 18 Lib/E PDF Book Based on the teleplay by Rod Serling. Sign In. Overall, a good book for the researcher and enthusiast. He used it and he misused it, and now he's just been handed the bill. Based on a teleplay by Charles Beaumont. Three astronauts return to Earth after seemingly having made an encounter that dooms them and their craft to erasure from existence itself. Recent updates. A henpecked book lover finds himself blissfully alone with his books after a nuclear war. A convict, living alone on an asteroid, receives from the police a realistic woman-robot. Continued from Part One. Constance does grow through the story. You've reached the maximum number of titles you can currently recommend for purchase. Based on an idea by Charles Beaumont and a teleplay by Jerry Sohl. Sue rated it really liked it Mar 21, The first human space colony is about to be rescued from the forsaken planet they've been on for three decades. An impoverished pawnbroker is granted four wishes by a genie in a bottle. The following episodes include stories that were adapted for radio from the original Twilight Zone television scripts, as well as original stories produced exclusively for this radio series. The problem isn't just that his wishes end up not being what he expected--it's what they did end up being. -

George Pal Papers, 1937-1986

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2s2004v6 No online items Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Processed by Arts Library-Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill; Arts Library-Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the George Pal 102 1 Papers, 1937-1986 Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 UCLA Arts Library-Special Collections Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: Art Library-Special Collections staff Date Completed: Unknown Encoded by: D.MacGill © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: George Pal Papers, Date (inclusive): 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 Origination: Pal, George Extent: 36 boxes (16.0 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Shelf location: Held at SRLF. Please contact the Performing Arts Special Collections for paging information. Language: English. Restrictions on Access Advance notice required for access. -

2004 World Fantasy Awards Information Each Year the Convention Members Nominate Two of the Entries for Each Category on the Awards Ballot

2004 World Fantasy Awards Information Each year the convention members nominate two of the entries for each category on the awards ballot. To this, the judges can add three or more nominees. No indication of the nominee source appears on the final ballot. The judges are chosen by the World Fantasy Awards Administration. Winners will be announced at the 2004 World Fantasy Convention Banquet on Sunday October 31, 2004, at the Tempe Mission Palms Hotel in Tempe, Arizona, USA. Eligibility: All nominated material must have been published in 2003 or have a 2003 cover date. Only living persons may be nominated. When listing stories or other material that may not be familiar to all the judges, please include pertinent information such as author, editor, publisher, magazine name and date, etc. Nominations: You may nominate up to five items in each category, in no particular order. You don't have to nominate items in every category but you must nominate in more than one. The items are not point-rated. The two items receiving the most nominations (except for those ineligible) will be placed on the final ballot. The remainder are added by the judges. The winners are announced at the World Fantasy Convention Banquet. Categories: Life Achievement; Best Novel; Best Novella; Best Short Story; Best Anthology; Best Collection; Best Artist; Special Award Professional; Special Award Non-Professional. A list of past award winners may be found at http://www.worldfantasy.org/awards/awardslist.html Life Achievement: At previous conventions, awards have been presented to: Forrest J. Ackerman, Lloyd Alexander, Everett F. -

PROGRESS REPORT 1 WSFA Press Congratulates Lewis Shiner Winner of the 1994 World Fantasy Award for Best Novel: Glimpses

PROGRESS REPORT 1 WSFA Press Congratulates Lewis Shiner Winner of the 1994 World Fantasy Award for Best Novel: Glimpses imited stock is available of LLewis Shiner’s WSFA Press collection THE EDGES “All in all, this is a highly OF THINGS, which features a readable collection.”Richard full-color wraparound jacket Grant, WASHINGTON POST, and four black-and-white inte May 26, 1991. riors by award-winning artist AliciaAustin, and an introduc “Cool short stories in a neat little package. You need tion by Mark L. Van Name. one.” Mark V. Ziesing, Limited to 600 numbered, ZIESING BOOKS. slipcased copies, all signed by Shiner, Austin, and Van Name. Contains 13 stories, four pub lished here for the first time; the remaining, including the author’s first published story, are specially revised for this publication. List Price: $45 (please add $3 for shipping). Order all three WSFA Press books and pay NO shipping fee. Winner, Readercon Small Press Award for Best Jacket Artwork. WSFA Press, Post Office Box 19951, Baltimore, MD 21211-0951 The 21st Annual World Fantasy Convention (WFC) meets Thursday, October 26 through Sunday, October 29, 1995, in Baltimore, Maryland, al the Inner Harbor Marriott. The theme of the convention is CELEBRATING THE CRAFT OF SHORT FICTION IN FANTASY AND HORROR Post Office Box 19909, Baltimore, MD 21211-0909 Online: (Genic) SFRT3, Category 25, Topic 3 GUESTS OF HONOR Writers: Terry Bisson, Lucius Shepard, Howard Waldrop Artist: Rick Berry Publisher: Lloyd Arthur Eshbach Toastmaster: Edward W. Bryant, Jr. REGISTRATION 'his is the first WFC on the East Coast in nearly a decade, so we expect the 750 memberships to sell quickly. -

Sfsfs Shuttle

SFSFS SHUTTLE *85 CONTENTS 3 Meeting News 4 Editorials 5 Book Reviews - Gerry Adair 7 Book Reviews - Arlene Garcia 8 News 9 It Came in the Mail 10 LOC’s 11 Current Membership List 14FANAC 15 DEJA VU by C W Dunbar 16 T-XI Ad 17 Membership Application 18 Birthdays TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT As a matter of courtesy, articles submitted Shuttle Crew to newspapers or magazines about SFSFS or Editors: SFSFS members, should be presented to the Don Cochran, Fran Mullen Board for clarification and proofing. Contributors: Gerry Adair, Arlene Garcia, Clif Dunbar Correspondence should be addressed to: Cover: SFSFS Shuttle Editor The incomparable Phil Tortorici PO Box 70143 Art: Fort Lauderdale, FL 33307-0143 Phil Tortorici, ?, Linda Michaels, Peggy or E-Mailed to Fran Mullen via Ranson, PAM CompuServe # 76137,3645 Shuttle Logo: COA’s should be sent Phil Tortorici to the SFSFS Secretary SFSFS Logo: at the above PO Box Gail Bennett Deadline for April Shuttle: Saturday, April 25 The SFSFS SHUTTLE April 1992 #85 The South Florida Science Fiction Society is a Florida non-profit educational corporation recognized by the Internal Revenue Service under Section 501 (c) (3). General membership is $15 per year ($1 for children). Subscribing membership is $1 per issue. The views, reviews, and opinions expressed in the SFSFS SHUTTLE are those of the authors and artists and not necessarily those of the publisher. And so it goes ... SEMPER SURSUM April 1992 Issue #85 The Official SFSFS Newsletter APRIL MEETING BOOKLOVERS’ An additional juicy tidbit! Got a letter from WHEN: Saturday, April, 1:00pm Ward Arrington, of the Grove Antiquarian. -

DOUBLE:BILL Symposium

BRIAN W. ALDISS ALLEN KIM LANG POUL ANDERSON KEITH LAUMER PIERS ANTHONY FRITZ LEIBER ISAAC ASIMOV ROBERT A. W. LOWNDES CHARLES BEAUMONT RICHARD LUPOFF GREG BENFORD KATHERINE MacLEAN ALFRED BESTER anne McCaffrey JAMES BLISH J. FRANCIS McCOMAS ROBERT BLOCH DEAN MCLAUGHLIN ANTHONY BOUCHER P. SCHUYLER MILLER LEIGH BRACKETT MICHAEL MOORCOCK RAY BRADBURY LARRY NIVEN MARION ZIMMER BRADLEY ANDRE NORTON REGINALD BRETNOR ALAN E. NOURSE JOHN BRUNNER ANDREW J. OFFUTT KENNETH BULMER ALEXEI PANSHIN ---------------------------------------------- JOHN W. CAMPBELL EMIL PETAJA s JOHN CARNELL H. BEAM PIPER ’ TERRY CARR FREDERIK POHL SYMPOSIUM JOHN CHRISTOPHER ARTHUR PORGES 3r ARTHUR C. CLARKE DANNIE PLACHTA tr HAL CLEMENT MACK REYNOLDS I MARK CLIFTON JOANNA RUSS GROFF CONKLIN ERIC FRANK RUSSELL BASIL DAVENPORT FRED SABERHAGEN AVRAM DAVIDSON JAMES H. SCHMITZ B io HANK DAVIS T. L. SHERRED CHARLES DE VET ROBERT SILVERBERG LESTER DEL REY CLIFFORD D. SIMAK AUGUST DERLETH E. E. 'DOC SMITH PHILIP K. DICK GEORGE 0. SMITH GORDON R. DICKSON JERRY SOHL jllopii HARLAN ELLISON NORMAN SPINRAD PHILIP JOSE FARMER THEODORE STURGEON DANIEL F. GALOUYE JEFF SUTTON DAVID GERROLD WILLIAM F. TEMPLE H. L. GOLD THEODORE L. THOMAS MARTIN GREENBERG WILSON TUCKER JAMES E. GUNN PIERRE VERSINS EDMOND HAMILTON KURT VONNEGUT, JR. double-.bill HARRY HARRISON TED WHITE ZENNA HENDERSON KATE WILHELM JOE HENSLEY ROBERT MOORE WILLIAMS JOHN JAKES JACK WILLIAMSON LEO P. KELLEY RICHARD WILSON DAMON KNIGHT ROBERT F. YOUNG DEAN R. KOONTZ ROGER ZELAZNY $3. the DOUBLE BILL Symposium ...being 94 replies to 'A Questionnaire for Professional Science Fiction Writers and Editors' as Created by: LLOYD BIGGLE, JR. Edited, and Published by: BILL MALLARDI & BILL BOWERS Bill BowersaBill Mallardi press 1969 Portions of this volume appeared in the amateur magazine Double:Bill. -

Mr. Monster 3

ometimes I think Earth has got to be the insane asylum of the universe. and I’m here by computer error. At sixty-eight, I hope I’ve gained some wisdom in the past fourteen lustrums and it’s obligatory to speak plain and true about the conclusions I’ve come to; now that I have been educated to believe by such mentors as Wells, Stapledon, Heinlein, van Vogt, Clarke, Pohl, (S. Fowler) SWright,S Orwell, Taine, Temple, Gernsback, Campbell and other seminal influences in scientifiction, I regret the lack of any female writers but only Radclyffe Hall opened my eyes outside sci-fi. I was a secular humanist before I knew the term. I have not believed in god since childhood’s end. I believe a belief in any deity is adolescent, shameful and dangerous. How would you feel, surrounded by billions of human beings taking Santa Claus, the Easter bunny, the tooth fairy and the stork seriously and capable of shaming, maiming or murdering in their name? I am embarrassed to live in a world retaining any faith in church, prayer or celestial creator. I do not believe in Heaven, Hell or a Hereafter; in angels, demons, ghosts, goblins, the Devil, vampires, ghouls, zombies, witches, warlocks, UFOs or other delusions and in very few mundane individuals - politicians, lawyers, judges, priests, militarists, censors and just plain people. I respect the individual’s right to abortion, suicide and euthanasia. I support birth control. I wish to Good that society were rid of smoking, drinking and drugs. My hope for humanity - and I think sensible science fiction has a