Subsurface Hydrology of an Overdeepened Cirque Glacier ∗ Christine F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY of the SCOTT GLACIER and WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA

This dissertation has been /»OOAOO m icrofilm ed exactly as received MINSHEW, Jr., Velon Haywood, 1939- GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Geology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Velon Haywood Minshew, Jr. B.S., M.S, The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by -Adviser Department of Geology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report covers two field seasons in the central Trans- antarctic Mountains, During this time, the Mt, Weaver field party consisted of: George Doumani, leader and paleontologist; Larry Lackey, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant. The Wisconsin Range party was composed of: Gunter Faure, leader and geochronologist; John Mercer, glacial geologist; John Murtaugh, igneous petrclogist; James Teller, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant; Harry Gair, visiting strati- grapher. The author served as a stratigrapher with both expedi tions . Various members of the staff of the Department of Geology, The Ohio State University, as well as some specialists from the outside were consulted in the laboratory studies for the pre paration of this report. Dr. George E. Moore supervised the petrographic work and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr. J. M. Schopf examined the coal and plant fossils, and provided information concerning their age and environmental significance. Drs. Richard P. Goldthwait and Colin B. B. Bull spent time with the author discussing the late Paleozoic glacial deposits, and reviewed portions of the manuscript. -

Baseline Water Quality Inventory for the Southwest Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network, Kenai Fjords National Park

Baseline Water Quality Inventory for the Southwest Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network, Kenai Fjords National Park Laurel A. Bennett National Park Service Southwest Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network 240 W. 5th Avenue Anchorage, AK 99501 April 2005 Report Number: NPS/AKRSWAN/NRTR-2005/02 Funding Source: Southwest Alaska Network Inventory and Monitoring Program, National Park Service File Name: BennettL_2005_KEFJ_WQInventory_Final.doc Recommended Citation: Bennett, L. 2005. Baseline Water Quality Inventory for the Southwest Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network, Kenai Fjords National Park. USDI National Park Service, Anchorage, AK Topic: Inventory Subtopic: Water Theme Keywords: Reports, inventory, freshwater, water quality, core parameters Placename Keywords: Alaska, Kenai Fjords National Park, Southwest Alaska Network, Aialik Bay, McCarty Fjord, Harrison Bay, Two Arm Bay, Northwestern Fjord, Nuka River, Delight Lake Kenai Fjords Water Quality Inventory - SWAN Abstract A reconnaissance level water quality inventory was conducted at Kenai Fjords National Park during May through July of 2004. This project was initiated as part of the National Park Service Vital Signs Inventory and Monitoring Program in an effort to collect water quality data in an area where little work had previously been done. The objectives were to collect baseline information on the physical and chemical characteristics of the water resources, and, where possible, relate basic water quality parameters to fish occurrence. Water temperatures in Kenai Fjords waters generally met the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) regulatory standards for both drinking water and growth and propagation of fish, shellfish, other aquatic life and wildlife. Water temperature standard are less than or equal to 13° C for spawning and egg and fry incubation, or less than or equal to 15° C for rearing and migration (DEC 2003). -

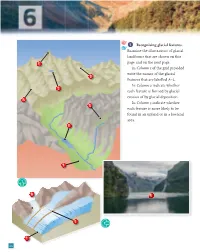

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Introduction to Geological Process in Illinois Glacial

INTRODUCTION TO GEOLOGICAL PROCESS IN ILLINOIS GLACIAL PROCESSES AND LANDSCAPES GLACIERS A glacier is a flowing mass of ice. This simple definition covers many possibilities. Glaciers are large, but they can range in size from continent covering (like that occupying Antarctica) to barely covering the head of a mountain valley (like those found in the Grand Tetons and Glacier National Park). No glaciers are found in Illinois; however, they had a profound effect shaping our landscape. More on glaciers: http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/10ad.html Formation and Movement of Glacial Ice When placed under the appropriate conditions of pressure and temperature, ice will flow. In a glacier, this occurs when the ice is at least 20-50 meters (60 to 150 feet) thick. The buildup results from the accumulation of snow over the course of many years and requires that at least some of each winter’s snowfall does not melt over the following summer. The portion of the glacier where there is a net accumulation of ice and snow from year to year is called the zone of accumulation. The normal rate of glacial movement is a few feet per day, although some glaciers can surge at tens of feet per day. The ice moves by flowing and basal slip. Flow occurs through “plastic deformation” in which the solid ice deforms without melting or breaking. Plastic deformation is much like the slow flow of Silly Putty and can only occur when the ice is under pressure from above. The accumulation of meltwater underneath the glacier can act as a lubricant which allows the ice to slide on its base. -

Jökulhlaups in Skaftá: a Study of a Jökul- Hlaup from the Western Skaftá Cauldron in the Vatnajökull Ice Cap, Iceland

Jökulhlaups in Skaftá: A study of a jökul- hlaup from the Western Skaftá cauldron in the Vatnajökull ice cap, Iceland Bergur Einarsson, Veðurstofu Íslands Skýrsla VÍ 2009-006 Jökulhlaups in Skaftá: A study of jökul- hlaup from the Western Skaftá cauldron in the Vatnajökull ice cap, Iceland Bergur Einarsson Skýrsla Veðurstofa Íslands +354 522 60 00 VÍ 2009-006 Bústaðavegur 9 +354 522 60 06 ISSN 1670-8261 150 Reykjavík [email protected] Abstract Fast-rising jökulhlaups from the geothermal subglacial lakes below the Skaftá caul- drons in Vatnajökull emerge in the Skaftá river approximately every year with 45 jökulhlaups recorded since 1955. The accumulated volume of flood water was used to estimate the average rate of water accumulation in the subglacial lakes during the last decade as 6 Gl (6·106 m3) per month for the lake below the western cauldron and 9 Gl per month for the eastern caul- dron. Data on water accumulation and lake water composition in the western cauldron were used to estimate the power of the underlying geothermal area as ∼550 MW. For a jökulhlaup from the Western Skaftá cauldron in September 2006, the low- ering of the ice cover overlying the subglacial lake, the discharge in Skaftá and the temperature of the flood water close to the glacier margin were measured. The dis- charge from the subglacial lake during the jökulhlaup was calculated using a hypso- metric curve for the subglacial lake, estimated from the form of the surface cauldron after jökulhlaups. The maximum outflow from the lake during the jökulhlaup is esti- mated as 123 m3 s−1 while the maximum discharge of jökulhlaup water at the glacier terminus is estimated as 97 m3 s−1. -

An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250

The Ohio Naturalist, PUBLISHED BY The Biological Club of the Ohio State University. Volume VIII. JANUARY. 1908. No. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS. SCHEPFEL—An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250 AN ESKER GROUP SOUTH OF DAYTON, OHIO.1 EARL R. SCHEFFEL Contents. Introduction. General Discussion of Eskers. Preliminary Description of Region. Bearing on Archaeology. Topographic Relations. Theories of Origin. Detailed Description of Eskers. Kame Area to the West of Eskers. Studies. Proximity of Eskers. Altitude of These Deposits. Height of Eskers. Composition of Eskers. Reticulation. Rock Weathering. Knolls. Crest-Lines. Economic Importance. Area to the East. Conclusion and Summary. Introduction. This paper has for its object the discussion of an esker group2 south of Dayton, Ohio;3 which group constitutes a part of the first or outer moraine of the Miami Lobe of the Late Wisconsin ice where it forms the east bluff of the Great Miami River south of Dayton.4 1. Given before the Ohio Academy of Science, Nov. 30, 1907, at Oxford, O., repre- senting work performed under the direction of Professor Frank Carney as partial requirement for the Master's Degree. 2. F: G. Clapp, Jour, of Geol., Vol. XII, (1904), pp. 203-210. 3. The writer's attention was first called to the group the past year under the name "Morainic Ridges," by Professor W. B. Werthner, of Steele High School, located in the city mentioned. Professor Werthner stated that Professor August P. Foerste of the same school and himself had spent some time together in the study of this region, but that the field was still clear for inves- tigation and publication. -

Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2019-07-01 Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA Natalie Shepherd Barkdull Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Barkdull, Natalie Shepherd, "Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 8590. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8590 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA Natalie Shepherd Barkdull A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Gregory T. Carling, Chair Barry R. Bickmore Stephen T. Nelson Department of Geological Sciences Brigham Young University Copyright © 2019 Natalie Shepherd Barkdull All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA Natalie Shepherd Barkdull Department of Geological Sciences, BYU Master of Science Shrinking alpine glaciers alter the geochemistry of sensitive mountain streams by exposing reactive freshly-weathered bedrock and releasing decades of atmospherically-deposited trace elements from glacier ice. Changes in the timing and quantity of glacial melt also affect discharge and temperature of alpine streams. -

Impact of Climate Change in Kalabaland Glacier from 2000 to 2013 S

The Asian Review of Civil Engineering ISSN: 2249 - 6203 Vol. 3 No. 1, 2014, pp. 8-13 © The Research Publication, www.trp.org.in Impact of Climate Change in Kalabaland Glacier from 2000 to 2013 S. Rahul Singh1 and Renu Dhir2 1Reaserch Scholar, 2Associate Professor, Department of CSE, NIT, Jalandhar - 144 011, Pubjab, India E-mail: [email protected] (Received on 16 March 2014 and accepted on 26 June 2014) Abstract - Glaciers are the coolers of the planet earth and the of the clearest indicators of alterations in regional climate, lifeline of many of the world’s major rivers. They contain since they are governed by changes in accumulation (from about 75% of the Earth’s fresh water and are a source of major snowfall) and ablation (by melting of ice). The difference rivers. The interaction between glaciers and climate represents between accumulation and ablation or the mass balance a particularly sensitive approach. On the global scale, air is crucial to the health of a glacier. GSI (op cit) has given temperature is considered to be the most important factor details about Gangotri, Bandarpunch, Jaundar Bamak, Jhajju reflecting glacier retreat, but this has not been demonstrated Bamak, Tilku, Chipa ,Sara Umga Gangstang, Tingal Goh for tropical glaciers. Mass balance studies of glaciers indicate Panchi nala I , Dokriani, Chaurabari and other glaciers of that the contributions of all mountain glaciers to rising sea Himalaya. Raina and Srivastava (2008) in their ‘Glacial Atlas level during the last century to be 0.2 to 0.4 mm/yr. Global mean temperature has risen by just over 0.60 C over the last of India’ have documented various aspects of the Himalayan century with accelerated warming in the last 10-15 years. -

Erosional and Depositional Study Guide

Erosional and Depositional Study Guide Erosional 32. (2pts) Name the two ways glaciers erode the bed. 33. (6pts) Explain abrasion. Use the equation for abrasion to frame your answer. 34. (3pts) Contrast the hardness of ice compared to the hardness of bedrock. What is doing the abrading and why? 35. (3pts) Contrast the normal stress (weight of the ice) on the rock tool in the ice compared to the contact pressure. Are they the same, different? Why? 36. (3pts) The tools in the ice abrade along with the bedrock so the tools must be replenished for the glacier to erode over its entire base. What is the source of the tools? Explain. 37. (3pts) What is the role of subglacial hydrology in abrasion? Explain. 38. (3pts) Although we did not explicitly discuss this in class, consider abrasion and bulk erosion in a deforming subglacial till. Explain what might be happening. 39. (2 pts) Name the two ways plucking occurs. 40. (5pts) Explain how plucking occurs at a step in the bedrock. 41. (3pts) What is a roche mountonee and how does it form? 42. (3pts) Name 3 erosional landscapes created by glaciers. Do not include roche mountonee and U-shaped valley. 43. (6pts) How does a U-shaped valley form? Be specific. Depositional 44. (3pts) How does a glacier transport rock debris? 45. (3pts) Where do you find lateral moraines on a glacier and what glacial processes determine their location? Draw a plan view diagram of a glacier, identify its relevant parts and the locations of lateral moraines. 46. (3pts) In class we discussed how the vertical extent of moraines is not correlated with glacier size. -

Glacial Processes and Landforms

Glacial Processes and Landforms I. INTRODUCTION A. Definitions 1. Glacier- a thick mass of flowing/moving ice a. glaciers originate on land from the compaction and recrystallization of snow, thus are generated in areas favored by a climate in which seasonal snow accumulation is greater than seasonal melting (1) polar regions (2) high altitude/mountainous regions 2. Snowfield- a region that displays a net annual accumulation of snow a. snowline- imaginary line defining the limits of snow accumulation in a snowfield. (1) above which continuous, positive snow cover 3. Water balance- in general the hydrologic cycle involves water evaporated from sea, carried to land, precipitation, water carried back to sea via rivers and underground a. water becomes locked up or frozen in glaciers, thus temporarily removed from the hydrologic cycle (1) thus in times of great accumulation of glacial ice, sea level would tend to be lower than in times of no glacial ice. II. FORMATION OF GLACIAL ICE A. Process: Formation of glacial ice: snow crystallizes from atmospheric moisture, accumulates on surface of earth. As snow is accumulated, snow crystals become compacted > in density, with air forced out of pack. 1. Snow accumulates seasonally: delicate frozen crystal structure a. Low density: ~0.1 gm/cu. cm b. Transformation: snow compaction, pressure solution of flakes, percolation of meltwater c. Freezing and recrystallization > density 2. Firn- compacted snow with D = 0.5D water a. With further compaction, D >, firn ---------ice. b. Crystal fabrics oriented and aligned under weight of compaction 3. Ice: compacted firn with density approaching 1 gm/cu. cm a. -

Analysis of Groundwater Flow Beneath Ice Sheets

SE0100146 Technical Report TR-01-06 Analysis of groundwater flow beneath ice sheets Boulton G S, Zatsepin S, Maillot B University of Edinburgh Department of Geology and Geophysics March 2001 Svensk Karnbranslehantering AB Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co Box 5864 SE-102 40 Stockholm Sweden Tel 08-459 84 00 +46 8 459 84 00 Fax 08-661 57 19 +46 8 661 57 19 32/ 23 PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ALL OF THE MISSING PAGES IN THIS DOCUMENT WERE ORIGINALLY BLANK Analysis of groundwater flow beneath ice sheets Boulton G S, Zatsepin S, Maillot B University of Edinburgh Department of Geology and Geophysics March 2001 This report concerns a study which was conducted for SKB. The conclusions and viewpoints presented in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily coincide with those of the client. Summary The large-scale pattern of subglacial groundwater flow beneath European ice sheets was analysed in a previous report /Boulton and others, 1999/. It was based on a two- dimensional flowline model. In this report, the analysis is extended to three dimensions by exploring the interactions between groundwater and tunnel flow. A theory is develop- ed which suggests that the large-scale geometry of the hydraulic system beneath an ice sheet is a coupled, self-organising system. In this system the pressure distribution along tunnels is a function of discharge derived from basal meltwater delivered to tunnels by groundwater flow, and the pressure along tunnels itself sets the base pressure which determines the geometry of catchments and flow towards the tunnel. -

Protecting the Crown: a Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park

Protecting the Crown A Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) RM-CESU Cooperative Agreement H2380040001 (WASO) RM-CESU Task Agreement J1434080053 Theodore Catton, Principal Investigator University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Diane Krahe, Researcher University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Deirdre K. Shaw NPS Key Official and Curator Glacier National Park West Glacier, Montana 59936 June 2011 Table of Contents List of Maps and Photographs v Introduction: Protecting the Crown 1 Chapter 1: A Homeland and a Frontier 5 Chapter 2: A Reservoir of Nature 23 Chapter 3: A Complete Sanctuary 57 Chapter 4: A Vignette of Primitive America 103 Chapter 5: A Sustainable Ecosystem 179 Conclusion: Preserving Different Natures 245 Bibliography 249 Index 261 List of Maps and Photographs MAPS Glacier National Park 22 Threats to Glacier National Park 168 PHOTOGRAPHS Cover - hikers going to Grinnell Glacier, 1930s, HPC 001581 Introduction – Three buses on Going-to-the-Sun Road, 1937, GNPA 11829 1 1.1 Two Cultural Legacies – McDonald family, GNPA 64 5 1.2 Indian Use and Occupancy – unidentified couple by lake, GNPA 24 7 1.3 Scientific Exploration – George B. Grinnell, Web 12 1.4 New Forms of Resource Use – group with stringer of fish, GNPA 551 14 2.1 A Foundation in Law – ranger at check station, GNPA 2874 23 2.2 An Emphasis on Law Enforcement – two park employees on hotel porch, 1915 HPC 001037 25 2.3 Stocking the Park – men with dead mountain lions, GNPA 9199 31 2.4 Balancing Preservation and Use – road-building contractors, 1924, GNPA 304 40 2.5 Forest Protection – Half Moon Fire, 1929, GNPA 11818 45 2.6 Properties on Lake McDonald – cabin in Apgar, Web 54 3.1 A Background of Construction – gas shovel, GTSR, 1937, GNPA 11647 57 3.2 Wildlife Studies in the 1930s – George M.