Foreign Aid and State Coercion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Underground Power Records List 4 -2020.P[...]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9709/underground-power-records-list-4-2020-p-459709.webp)

Underground Power Records List 4 -2020.P[...]

This is the last List that will be sent to all emails on our previous email distributor - we will build up a new one. So all friends who order for sure will be on the new distributor. All others please send a short message and we will add you too for sure. The list will be also on our website and we will announce ever new one on facebook. Our own new releases will be on the next List (Xmas or January)! Das ist die letzte Liste die an den alten email Verteiler geschickt wird - wir bauen einen Neuen auf. Alle Besteller werden automatisch in den neuen aufgenommen. Alle Anderen die den Newsletter erhalten möchten senden bitte eine kurze Bestätigung, dass Sie künftig auch wieder in den Verteiler aufgenommen werden wollen. Die Liste wird auch auf unserer Webseite veröffentlicht und immer auf facebook angekündigt. Unsere eigenen neuen Releases werden auf der nächsten Liste erscheinen (um Weihnachten oder im Januar) ! CD ADORNED GRAVES – Being towards a River (NEW*EPIC/THRASH METAL*TOURNIQUET*DELIVERANCE) - 14 GER Private Press 2020 – Brandnew Oldschool 80’s Epic / Thrash Metal with elements of Epic Doom / Death Metal from Germany ! For Fans of Vengeance Rising, Tourniquet, Deliverance, Believer, Martyr / Betrayal or Metallica and Slayer, but also Black Sabbath + Trouble ! Melodic Old School Epic Doom N Thrash Death Metal Einschlägen, der Einfachheit halber als „Thrash Metal“. ALCATRAZZ - Born Innocent (NEW*MELODIC METAL*G.BONNET*RAINBOW*MSG*TNT) - 15 Silver Lining Music 2020 - Brandnew limited CD Digipak Fantastic Melodic Metal / Hard Rock with Original Line up Graham Bonnet, Keyboarder Jimmy Waldo and Bassplayer Gary Shea – now together with Guitar Hero Joe Stump and some fantastic guest musicians: Chris Impellitteri, Bob Kulick, Nozumu Wakai, Steve Vai, Dario Mollo, Don Van Stavern or Jeff Waters For Fans of RAINBOW, TNT, EUROPE, DOKKEN, MICHAEL SCHENKER ANGEL WITCH – Screamin’ ‘n’ Bleedin’ (NEW*LIM.500*NWOBHM CLASSIC 1985) – 18 € N.W.O.B.H.M. -

HIGHLIGHTS Videos Biography Contacts Website Facebook

biography D.D. Verni is an American bassist, songwriter, and producer, best known for his work with the band OVERKILL. Overkill released their first record in 1985 and with their contemporaries (Metallica, Slayer, Megadeth, Anthrax) helped define a new genre of music, “thrash metal”. Overkill have released D.D. VERNI 18 full-length albums as well as two live albums and EPs, and several DVDs. D.D. Verni released his first solo album, “Barricade”, in October of 2018. The record, which was mixed and mastered by Chris “Zeuss” Harris (ROB ZOMBIE, QUEENSRŸCHE, HATEBREED), is a mix of all of Verni’s influences. “There’s some metal, punk, and classic rock... it’s all in there, from QUEEN to GREEN DAY to METALLICA, I think we covered all the basses!” declares D.D. The album also features a host of guitar players doing guest spots, including Jeff Loomis (ARCH ENEMY), Angus Clark (TRANS SIBERIAN ORCHESTRA), Jeff Waters (ANNIHILATOR), Bruce Franklin (TROUBLE), Mike Romeo (SYMPHONY X), Mike Orlando (ADRENALINE MOB), Steve Leonard (ALMOST QUEEN), and Andre HIGHLIGHTS “Virus” Karkos (DOPE), who also contributed the rhythm guitar tracks. Rounding out the recording line-up is former OVERKILL drummer Ron Lipnicki. • Founding member, bassist, & songwriter for thrash metal pioneers, “I’m psyched to get this disc out,” states Verni. “We had a lot of fun and a lot of great players contributed.” • 18 studio albums released with • millionS of albums sold worldwide with • Vocalist, bassist, & songwriter in BRONX CASKET CO. with 4 albums released • Debut solo album, “Barricade”, released in October 2018 featuring notable guests such as videos Jeff Loomis (ARCH ENEMY), Angus Clark (TRANS SIBERIAN ORCHESTRA), & Jeff Waters (ANNIHILATOR), among others Fire Up Lost in The Undergrond night of the swamp king contacts Worldwide Management: Jeff Keller / The Artery Foundation [email protected] North America Booking: Mike Monterulo / TKO [email protected] Europe Booking: Dolores Lokas / Headline Concerts [email protected]. -

Annihilator - Alice in Hell

Annihilator - Alice in Hell Scritto da Gianluca Livi Venerdì 01 Gennaio 2021 13:59 Ci entraAlice di diritto, in Hell, nella categoria "masterpiece". Questo favolosoAnnihilator escedebutto nel discografico1989 e fa capire dei canadesi ai signori del thrash statunitense che in Nord America ci sono allievi perfettamente in grado di superare i maestri. Il pezzo Alisonche trascina Hell" rappresenta l'album,Spanish "il perfetto" Flydi Eddieconnubio Van, rendetra Halen aspirazioni l'introRide Theacustico "da Lightning classifica di robetta" e altissima per adolescenti qualità esecutivamaldestri. e compositiva, ed è anticipato da un arpeggio di chitarra acustica che, rivaleggiando con " La mini suiteSchizo " (Are", divisa Never in due Alone) parti, anticiperebbe di poco la nascita del prog metal a vocazione durissima se non fosse che il combo lo condisce con del sano techno thrash, giusto per far capire chi è che comanda effettivamente. Tutto il restoAnthrax dell'album per la strada riesceJoe Belladonna (cona ,seminare la la cui sola voceSlayer eccezioneimpietosamente è effettivamente, in quanto di Megadeth gliad un aggressività, ,traguardo per ciò che inarrivabile e concerne per i cambi ogni dialtro tempo, gruppo e lo thrash) fa con ela a disinvoltura rivaleggiare di con chi ilè meglioperfettamente di capace di passare da uno stille all'altro con consapevole determinazione e sicurezza. Anche ilAlice titolo inè da". Wonderland manuale, efficace, come è, nel suo parodiare " Questo non è un album di thrash, ma l'album di thrash per eccellenza, il cui unico difetto, rispetto ai lavori discografici dei gruppi sopra citati, è quello di essere uscito fuori tempo massimo, a ridosso dell'esplosione grunge, quindi ben lontano dall'inventare un genere, limitandosi semplicemente a perfezionarlo, ancorché in termini eccelsi. -

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

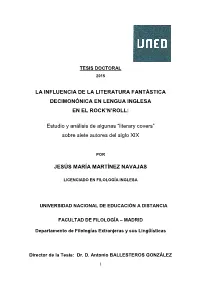

TESIS DOCTORAL 2015 LA INFLUENCIA DE LA LITERATURA FANTÁSTICA DECIMONÓNICA EN LENGUA INGLESA EN EL ROCK’N’ROLL: Estudio y análisis de algunas “literary covers” sobre siete autores del siglo XIX POR JESÚS MARÍA MARTÍNEZ NAVAJAS LICENCIADO EN FILOLOGÍA INGLESA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN A DISTANCIA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA – MADRID Departamento de Filologías Extranjeras y sus Lingüísticas Director de la Tesis: Dr. D. Antonio BALLESTEROS GONZÁLEZ 1 - DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍAS EXTRANJERAS Y SUS LINGÜISTICAS, FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA. - TÍTULO DE LA TESIS: LA INFLUENCIA DE LA LITERATURA FANTÁSTICA DECIMONÓNICA EN LENGUA INGLESA EN EL ROCK’N’ROLL: ESTUDIO Y ANÁLISIS DE ALGUNAS “LITERARY COVERS” SOBRE SIETE AUTORES DEL SIGLO XIX. - AUTOR: JESÚS MARÍA MARTÍNEZ NAVAJAS (LICENCIADO EN FILOLOGÍA INGLESA). - DIRECTOR DE TESIS: DR. D. ANTONIO BALLESTEROS GONZÁLEZ. 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS Este trabajo está dedicado muy especialmente a mis padres Teresa y Jesús, sin cuyo apoyo y respaldo no habría sido posible esta investigación, por darme todo el amor y una educación de libre pensamiento y ser el faro que guía mi desarrollo intelectual y mi existencia. AsImismo, a mis hermanos Pablo, Andrés y Paloma, y a mi compañera Giuliana por su inagotable paciencia y cariño. Gracias, familia. Vaya un agradecimiento muy especial para la Dra. Dª María del Carmen González Landa por la gran ayuda y todo lo que me ha transmitido. También quiero agradecer a Iñaki Osés y la Eguzki Irratia de Pamplona por haberme brindado la oportunidad de difundir mis conocimientos literarios y musicales a través de las ondas radiofónicas. Como no podía ser de otra manera deseo expresar mi agradecimiento al Dr. -

Canada's ANNIHILATOR Is the Lifework Of

2018 Canada’s ANNIHILATOR is the lifework of guitarist Jeff Waters. Founded in 1984, the band took the metal scene by storm with their debut 1989 release “Alice In Hell”, upped the ante with 1990’s “Never, Neverland” and has not stopped continually releasing records (16 studio records) and touring the world (mostly all outside North America), ever since; cementing ANNIHILATOR as the biggest-selling Heavy Metal act, outside of Canada, in Canada’s history. Cited by members of bands the likes of Megadeth, Pantera, Nickelback, 3 Doors Down, Dream Theater, Children Of Bodom, Lamb of God, Opeth, Trivium, In Flames, Arch Enemy and countless musicians and Thrash/Heavy Metal bands around the world as having some influence on their music, guitarist/vocalist Jeff Waters has continued to fly the Canadian flag for his own brand of metal across the globe for 29 years. The last 3 years has seen a dramatic rise in the popularity of the band worldwide after the 2015 “Suicide Society” and 2017 “For The Demented” studio releases and more than 2 years of touring. Expect a new studio cd in 2019 and some non-stop touring presence in Europe, starting with this summer’s (2018) festival appearances and the much-anticipated “A Tour For The Demented” Headline tour from Oct.-Dec. 2018 through Europe. Jeff Waters (vocals/guitar), Rich Hinks (bass), Aaron Homma (guitar), Fabio Alessandrini (drums) Record Label: Booking Agency: Silver Lining Music Ltd. Seaside Touring GmbH & Co. KG Serena Furlan Thomas Kreidner [email protected] [email protected] -

A Final Chapter

A FINAL CHAPTER Compiled By J. L. HERRERA A FINAL CHAPTER DEDICATED TO: The memory of my father, Godfrey (‘Geoff’) Allman Clarke; who saw a good book and a comfortable chair as true pleasures … AND WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: Mirka Hercun-Facilli, Eve Masterman, Ellen Naef, Cheryl Perriman, Patrick Herrera, Sheila Given, Marie Cameron, Poppy Lopatniuk, and the Meeting House Library. INTRODUCTION So much for thinking it was time to cut and run, or descend heavily into a comfortable armchair, and say “No more”. I did actually say just that. And then the old itch came over me. Like someone becoming antsy at the sight of a card table or roulette wheel. One more go won’t hurt— The trouble is—the world may be drowning under books most of which I don’t particularly want to read but there are always those which throw up an idea, a thought, a curiosity, a sense of delight, a desire to know more about someone or something. They sneak in when I’m not on guard. I say “I wonder—” before I realise the implications. On the other hand they, the ubiquitous ‘they’, keep telling us ordinary mortals to use our brains. Although I think that creating writers’ calendars is the ultimate in self-indulgence I suppose it can be argued that it does exercise my brain. And as I am hopeless at crossword puzzles but don’t want my brain to turn into mush … here we go round the mulberry bush and Pop! goes the weasel, once more. I wonder who wrote that rhyme? At a guess I would say that wonderful author Anon but now I will go and see if I can answer my question and I might be back tomorrow to write something more profound. -

Metal Bulletin Zine #43 Washington State, U.S

Metal Bulletin Zine #43 Washington state, U.S. www.metalbulletin.blogspot.com www.facebook.com/pages/The-Metal-Bulletin-paper-zine in this issue: reviews, reports, news, interviews on: Astral Domine (Italy) Lucifer’s Hammer (Chile) Tabahi (Pakistan) Obelyskkh (Germany) DEATH METAL Blasphemyth (Morocco/Switzerland), Humiliation (Malaysia), The Kennedy Veil (U.S.), Near Death Condition (Switzerland), Obscure Infinity (Germany), Otargos (France), Warfather (Holland/Brazil/U.S.), Warmaster (Holland) BACK TO THE FUTURE Manilla Road (U.S.), Revelation (U.S.), Sarcófago (Brazil), “Warfare Noise” (Brazil) www.fuglymaniacs.com (issues online, concert videos, interviews, reviews) history of Metal Bulletin Zine #1-20: (2006-2009): Wisconsin #21-26: (2009-2010): Texas #27(2010)-- now; Washington state Metal Bullletin Zine (MBZ) is a homemade publication, think will happen because these riffs, this attitude, this and not a business enterprise in any way. MBZ is not vibe, these songs are originate from the book of heavy business partners with any band, metal. record/management/publicity company, club/bar, or Highly recommend for said listeners. any kind of for-profit organizations/individuals. MBZ is www.lucifershammer.bandcamp.com not paid money and does not sell any product to www.facebook.com/Lucifershammerband anyone for money/profit. -- -— Tabahi metal on the radio/internet (Pacific Time) Tabahi is all-out headbanging, moshing thrash, the way Metal Shop (Seattle, WA): Saturday 11pm-3am that both old and new thrashers can understand: KISW 99.9fm www.kisw.com shredding metal. Good news: the self-titled album is FOUR ridiculous hours of the heavy stuff! also a free pay-what-you-want release. -

Das Wacken Open Air in Zahlen

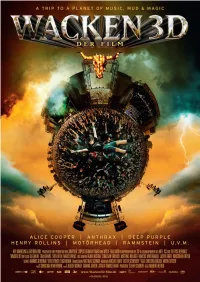

präsentiert Regie Norbert Heitker In den Hauptrollen Festivalbesucher u.a. aus Taiwan, Indien, USA, Deutschland und die „Metal Battle“- Teilnehmer Nine Treasures (Mongolei), Rotten State (Uruguay) und God - The Barbarian Horde (Rumänien) Und mit Auftritten von und Interviews mit Alice Cooper, Anthrax, Deep Purple, Henry Rollins, Motörhead, Rammstein und den Wacken-Gründern und -Organisatoren Thomas Jensen und Holger Hübner u.v.m. Eine Produktion von JUMPSEAT 3Dplus WÜSTE Film ZDF in Zusammenarbeit mit ARTE Produziert mit Förderung von Filmförderung Hamburg Schleswig-Holstein, Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg, Filmförderungsanstalt (FFA) und Deutscher Filmförderfonds (DFFF) KINOSTART: 24. JULI 2014 Im Verleih von NFP marketing & distribution* Im Vertrieb von Filmwelt Verleihagentur 2 VERLEIH NFP marketing & distribution* Kantstraße 54 10627 Berlin Tel. 030 – 232 554 213 www.NFP.de VERTRIEB Filmwelt Verleihagentur Rheinstraße 24 80803 München Tel. 089 – 27775 217 Fax: 089 – 27775 211 www.filmweltverleih.de PRESSEBETREUUNG boxfish films Raumerstraße 27 10437 Berlin Tel. 030 – 44044 753 / -691 Fax: 030 – 44044 691 [email protected] Weitere Presseinformationen und Bildmaterial stehen online für Sie bereit unter www.filmpresskit.de 3 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 6 Pressenotiz 8 Produktionsnotizen 15 „Es geht um die Kraft von Musik“ – Ein Gespräch mit Regisseur Norbert Heitker 19 „Wacken hat einen gewissen Spirit. Und der ist uns heilig.“ – Ein Gespräch mit Thomas Jensen, Gründer und Veranstalter des Wacken Open Air 22 „Jedes Mal ist wie eine Heimkehr“ – Eine Liebeserklärung von Doro Pesch 24 „Wacken ist purer Rock’n Roll“ – von Thorsten Zahn, Herausgeber und Chefredakteur des „Metal Hammer“ 26 Wacken ist… Das Wacken Open Air in Zahlen 28 Das Wacken Open Air – eine Historie 30 Die beteiligten Bands 30 Alice Cooper | Alpha Tiger | Annihilator | Anthrax | Anvil | Blaas of Glory 31 Deep Purple | Doro feat. -

The Cord Weekly

2 10 "24 CORDweeklythe LAURIER'S OFFICIAL STUDENT NEWSPAPER NEW I.T. FEE GOES MASSIVE women's hockey - - QUAKE VOLUME 41 WEDNESDAY, jANUARY 31 2001 ISSUE 20 TO REFERENDUM HITS SOUTH INDIA WINS THREE Schlegel Schematics In Students' Unit troubled with planning process DILLON MOORE The project will also include There have also been town CORD NEWS two other major changes to the hall meetings regarding the university grounds, billed as the addition and the plans have Construction of Laurier's first "Superbuild" project, and fund- been up for viewing in the major building plan in ten years ed by government capital Peters building for quite a is set to begin in just a few improvement funds. while. months' time, but the way in The library will be renovated Kroeker dismisses the above which the school is handling so that the bottom two floors, as advisory roles, and not the planning phase is fast which are now comprised directly involved with the deci- becoming a very contentious mainly of classroom space, will sion-making process. issue. be available for library purpos- Rosehart, however, dis- Students' Union president es. This will bring the library agrees. Jeffrey Kroeker has informed the closer to the accepted standards "Their advice is treated very Cord that he is in the process of for a university the size of seriously," said Rosehart. contacting legal counsel, and Wilfrid Laurier. According to him, the filing a formal complaint with The third part of the plan Aesthetics Committee is one of University President Dr. calls for an. addition of halls of the most powerful groups Rosehart, over what Kroeker tiered-seating classrooms to be involved in the planning alleges was a breach in the added in parallel behind the process. -

2010 Epiphone Catalog.Pdf

catalog 2010 Fifteen years or more ago, Epiphone instruments were being made at the same Asian guitar factories as most other competitive brands. The problem with that scenario is that it's difficult, if not impossible, to have a substantially better instrument than your competition when the parts, process and people who make them are the same. As a result, Epiphone established the first permanent presence by an American guitar brand in 1992 with the opening of our Epiphone Korea office which played a daily hands-on role in selecting and sourcing parts and materials as well as closely controlling quality. While that initial step was instrumental in moving towards continu- ous improvement and independence, Epiphone knew that ultimately it needed its own dedicated factory with its own employees. A team from Epiphone set out to change the guitar world as it was then known. Drawing on years of experience, Epiphone and Gibson U.S.A. personnel became intimately involved in facility layout, equipment design, training techniques and the establishment of quality control and by October of 2002, the Epiphone only Gibson Qingdao factory had become a reality. The effectiveness of combining Epiphone and Gibson expertise and experience with Asian production efficiencies ushered in a new era for Epiphone and brought about exceptional instruments at price points the average working musician could afford. That tradition continues today at Epiphone’s Gibson Qingdao (GQ) factory near Qingdao, China where only Epiphone instruments are crafted. To meet the growing demand for Epiphone instruments worldwide, Epiphone took another major step in 2008 with the opening of the second dedicated Epiphone factory, Epiphone Qingdao (EQ). -

Jeff Waters Von Annihilator Bei PPC Music

Kommt zu einer Guitar Clinic: Am 17.September können Gitarristen bei PPC Music Annihilaltor-Musiker Jeff Water auf der Finger schauen. Guitar Clinic nicht nur für Thrash-Metaller Jeff Waters von Annihilator bei PPC Music 15. August 2013, Von: Redaktion, Foto(s): PPC Music, Pressefreigabe Ob für Anfänger, Fortgeschrittene, Fans oder Musikenthusiasten im Allgemeinen: Instrumenten- und Technik-Workshops mit prominenten Musikern stoßen zuweilen auf ordentlich Resonanz. In Hannover lädt PPC Music des Öfteren deutschlandweit aber auch international renommierte Instrumentalisten ein, die auf unterschiedlichen Instrumenten in Workshops Einblicke in ihr Spiel, ihr Equipment und ihre Technik geben. Im September ist bei PPC Music wieder Jeff Waters von der Thrash-Metal-Band Annihilator zu Gast. Das Gitarrenspiel von Annihilator-Gitarrist und Bandgründer Jeff Waters gilt allgemein als besonders schnell, hart und dennoch melodiös. Als Stamminstrument nutzt Waters -und das dürfte für aktive Rock-und Metalgitarristen von Interesse sein- eine rote Epiphone-Signature-Flying-V-E-Gitarre. Am Dienstag, den 17.September wird Jeff Waters ab 19.00 Uhr bei PPC Music am Alten Flughafen in Hannover-Vahrenheide zu Gast sein und auf der Turmbühne des Instrumenten-und Equipmenthändlers eine ausführliche Guitar Clinic geben. Im Verlauf dessen will Waters den Teilnehmern unter anderem Einblicke in verschiedene Spieltechniken, Harmoniebildung und in seinen Alltag als Musiker geben. In der Vergangenheit seien Guitar Clinics wie diese sehr beliebt gewesen, weshalb es ratsam sei, sich verhältnismäßig schnell einen Platz bei der Veranstaltung zu sichern, teilt PPC Music per Meideninformation mit. 15. August 2013 1/2 © Rockszene.de 2021 Anmeldungen für die Guitar Clinic mit Jeff Waters werden per E-Mail unter guitar (ät) ppc-music.de entgegengenommen. -

Australian Indigenous LAW REVIEW

australian indigenous LAW REVIEW 2011 Volume 15, Number 1 A PUBLICATION OF THE INDIGENOUS LAW CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES www.ilc.unsw.edu.au ii australian indigenous LAW REVIEW 2011 Volume 15, Number 1 EDITORS Daniel Threlfall Daniel Wells Megan Davis Robert Woods EDITORIAL PANEL Thalia Anthony BA LLB PhD (Sydney) Toni Bauman BA (Macquarie) Sean Brennan BA LLB LLM (ANU) Ngiare Brown BMed (Newcastle) MPHTM (James Cook) FRACGP (Aust Coll GP) Claire Charters BA LLB (Hons) (Otago) LLM (NYU) Donna Craig BA LLM (Osgoode Hall) Kyllie Cripps BA (Hons) (South Aust) PhD (Monash) Chris Cunneen BA DipEd (UNSW) PhD (Sydney) Megan Davis BA LLB (UQ) GDLP LLM (ANU) Dalee Sambo Dorough MALD (Tufs) PhD (British Columbia) Brendan Edgeworth LLB (Hons) MA (Shefeld) Tim Goodwin BA LLB (Hons) (ANU) Brenda Gunn BA (Manitoba) JD (Toronto) LLM (Arizona) Jackie Hartley BA (Hons) LLB (UNSW) LLM (Arizona) Samantha Joseph BA LLB (UNSW) Peter Jull BA (Toronto) Patricia Lane BA LLB (Hons) LLM (Sydney) Terri Libesman BA LLB (Macquarie) Erin Mackay BA LLB (UNSW) GDLP (ANU) Hannah McGlade LLB LLM (Murdoch) Garth Netheim LLB (Sydney) AM (Tufs) Keryn Ruska LLB (Melbourne) GDLP (ANU) Sonia Smallacombe BA DipEd (Monash) BA (Hons) MA (Melbourne) Prue Vines BA MA (Sydney) DipEd (Syd Teach Coll) LLB (UNSW) STUDENT EDITORS Juliet Akello, Emmanuel Brennan, Kate Cora, Laura Ferraro, Katie Gilchrest, and Simon Lindsay STUDENT EDITORIAL PANEL Juliet Akello, Jefrey Beech, Laura Ferraro, Katie Gilchrest, Zoe Hankin, Jessica Holgerrson, Amanda Kazacos, and Xavier O’Halloran