Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jomon: 11Th to 3Rd Century BCE Yayoi

Outline Lecture Sixteen—Early Japanese Mythology and Shinto Ethics General Chronology: Jomon: 11th to 3rd century B.C.E. Yayoi: 3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E. Tomb: 3rd to 6th C.E. Yamato: 6th to 7th C.E. I) Prehistoric Origins a) Early Japanese history shrouded in obscurity i) Writing did not develop in Japan until 6th century C.E. ii) No remains of cities or other large scale settlements iii) Theories of origins of earliest settlers b) Jomon (Roughly 11th to 3rd century B.C.E.) i) “Rope-pattern” pottery ii) Hunter-gathering settlements iii) Lack of social stratification? c) Yayoi (3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E.) i) Simultaneous introduction of irrigation, bronze, and iron contributing to revolutionary changes (1) Impact of change in continental civilizations tend to be more gradual (2) In Japan, effect of changes are more dramatic due to its isolation (a) Foreign elements trickle in, then blend with indigenous elements (b) Creating a distinctive synthesis in “petri-dish” (pea-tree) environment ii) Increasing signs of specialization and social stratification (1) Objects of art—less primitive, more self-conscious (2) Late Yayoi burial practices d) Tomb or Kofun Period (3rd to 7th) i) Large and extravagant tombs in modern day Osaka ii) What beliefs about the afterlife do they reflect? (1) Two strains in Japanese religious cosmology iii) Emergence of a powerful mounted warrior class iv) Regional aristocracies each with its clan name (1) Uji vs. Be (2) Dramatic increase in social stratification e) Yamato State (6th to 8th C.E.) II) Yamato’s Constructions -

Ceramics Monthly Mar93 Cei03

William Hunt..................................... Editor Ruth C. Butler................. Associate Editor Robert L. Creager...................... Art Director Kim Nagorski..................Assistant Editor Mary Rushley................ Circulation Manager MaryE. Beaver ....Assistant Circulation Manager Connie Belcher.........Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis............................Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448 Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Profes sional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Bou levard, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, announcements, news releases, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations and digital TIFF images are welcome and will be considered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines: A book let describing standards and procedures for sub mitting materials is available upon request. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) index ing is available through Wilsonline, 950 Univer sity Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Company, 362 Lakeside Drive, Forest City, California 94404. -

Artful Adventures JAPAN an Interactive Guide for Families 56

Artful Adventures JAPAN An interactive guide for families 56 Your Japanese Adventure Awaits You! f See inside for details JAPAN Japan is a country located on the other side of the world from the United States. It is a group of islands, called an archipelago. Japan is a very old country and the Japanese people have been making beautiful artwork for thousands of years. Today we are going to look at ancient objects from Japan as well as more recent works of Japanese art. Go down the stairs to the lower level of the Museum. At the bottom of the steps, turn left and walk through the Chinese gallery to the Japanese gallery. Find a clay pot with swirling patterns on it (see picture to the left). This pot was made between 2,500 and 1,000 b.c., during the Late Jōmon period—it is between 3,000 and 4,500 years old! The people who lived in Japan at this time were hunter-gatherers, which means that they hunted wild animals and gathered roots and plants for food. The Jomon people started forming small communities, and began to make objects that were both beautiful and useful— like this pot which is decorated with an interesting pattern and was used for storage. Take a close look at the designs on this pot. Can you think of some words to describe these designs? Japanese, Middle to Late Jōmon period, ca. 3500–ca. 1000 B.C.: jar. Earthenware, h. 26.0 cm. 1. ............................................................................................................. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund (2002-297). -

Matrix: a Journal for Matricultural Studies “In the Beginning, Woman

Volume 02, Issue 1 March 2021 Pg. 13-33 Matrix: A Journal for Matricultural Studies M https://www.networkonculture.ca/activities/matrix “In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun”: Takamure Itsue’s Historical Reconstructions as Matricultural Explorations YASUKO SATO, PhD Abstract Takamure Itsue (1894-1964), the most distinguished pioneer of feminist historiography in Japan, identified Japan’s antiquity as a matricultural society with the use of the phrase ‘women-centered culture’ (josei chūshin no bunka). The ancient classics of Japan informed her about the maternalistic values embodied in matrilocal residence patterns, and in women’s beauty, intelligence, and radiance. Her scholarship provided the first strictly empirical verification of the famous line from Hiratsuka Raichō (1886-1971), “In the beginning, woman was the sun.” Takamure recognized matricentric structures as the socioeconomic conditions necessary for women to express their inner genius, participate fully in public life, and live like goddesses. This paper explores Takamure’s reconstruction of the marriage rules of ancient Japanese society and her pursuit of the underlying principles of matriculture. Like Hiratsuka, Takamure was a maternalist feminist who advocated the centrality of women’s identity as mothers in feminist struggles and upheld maternal empowerment as the ultimate basis of women’s empowerment. This epochal insight into the ‘woman question’ merits serious analytic attention because the principle of formal equality still visibly disadvantages women with children. Keywords Japanese women, Ancient Japan, matriculture, Takamure Itsue, Hiratsuka Raicho ***** Takamure Itsue (1894-1964), pionière éminente de l'historiographie feministe au Japon, a découvert dans l'antiquité japonaise une société matricuturelle qu'elle a identifiée comme: une 'société centrée sur les femmes' (josei chūshin no bunka) ou société gynocentrique. -

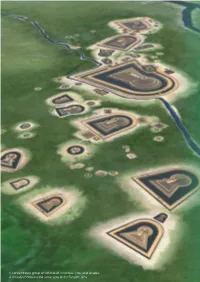

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1992 19/2-3 Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period I s h in o H ironobu 石野博信 The rituals of the Kofun period were closely connected with both daily life and political affairs. The chieftain presided over the principal rites, whether in the mountains, on the rivers, or along the roadsides. The chieftain’s funeral was the preeminent rite, with a tomb mound, or kofun, constructed as its finale. The many and varied kofun rituals have been discussed elsewhere;1 here I shall concentrate on other kami rites and their departure from Yayoi practices. A Ritual Revolution Around AD 190, following a period of warfare called the “Wa Unrest,” the overall leadership of Wa was assumed by Himiko [Pimiko], female ruler of the petty kingdom of Yamatai. Beginning in 239 she opened diplomatic relations with the Wei court in China as the monarch of Wa, and she died around 248. Makimuku 1 type pottery appeared around 190; in 220 or so it was followed by Makimuku 2,and then by Makimuku 3, in about 250. The 92-meter-long keyhole-shaped Makimuku Ishizuka tomb in Sakurai City, Nara, was constructed in the first half of the third century; in the latter half of the same century the Hashihaka tomb was built. Hence the reign of Himiko, circa 190 to 248,corresponds to the appearance of key hole-shaped tombs. It was the dawn of the Kofun period and a formative time in Kofun-period ritual. In the Initial Kofun, by which I mean the period traditionally assigned to the very end of the Yayoi, bronze ritual objects were smashed, dis * This article is a partial translation of the introductory essay to volume 3 of Ish in o et al. -

Origin of Shinto : Ancient Japanese Rituals

Kokugakuin Univercity Museum Origin of Shinto : Ancient Japanese Rituals 14 September (Sat.) - 10 December (Sun.) , 2017 № Title Provenance Date Collection ■ Introduction 1 Mirror with Design of Seven arcs Okinoshima site, Munakata city, Fukuoka pref. Kofun period, 4th century Owned by Kokugakuin University Museum ■ ChapterⅠ: What is "Sinto " ? 1:Views of "Shinto " in the "Nihon Shyoki " : "Shinto " as the state religion Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.21 Edited in 720, Nara period 2 Edited by Prince Toneri and others Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "The record before the enthronement of Emperor Yomei " Published in Edo period Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.25 Edited in 720, Nara period 3 Edited by Prince Toneri and others Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "The record before the enthronement of Emperor Kotoku " Published in Edo period Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.20 Edited in 720, Nara period 4 Edited by Prince Toneri and others Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "The record before the enthronement of Emperor Bidatsu" Published in Edo period Edited in 779, Nara period 5 To Daiwajo Toseiden (Eastern Expedition of the Great Tang Monk) Edited by Omi Mifune Owned by Kokugakuin University Library Published in Edo period Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan), vol.25 Edited in 720, Nara period 6 Edited by Prince Toneri Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "October, the 3rd year of Taika (647)" Published in Edo period 2:The word of "Shinto " : The Shinto view of the spirit Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.19 -

The Literary Landscape of Murakami Haruki

Akins, Midori Tanaka (2012) Time and space reconsidered: the literary landscape of Murakami Haruki. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/15631 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Time and Space Reconsidered: The Literary Landscape of Murakami Haruki Midori Tanaka Atkins Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Japanese Literature 2012 Department of Languages & Cultures School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Kamakura Period, Early 14Th Century Japanese Cypress (Hinoki) with Pigment, Gold Powder, and Cut Gold Leaf (Kirikane) H

A TEACHER RESOURCE 1 2 Project Director Nancy C. Blume Editor Leise Hook Copyright 2016 Asia Society This publication may not be reproduced in full without written permission of Asia Society. Short sections—less than one page in total length— may be quoted or cited if Asia Society is given credit. For further information, write to Nancy Blume, Asia Society, 725 Park Ave., New York, NY 10021 Cover image Nyoirin Kannon Kamakura period, early 14th century Japanese cypress (hinoki) with pigment, gold powder, and cut gold leaf (kirikane) H. 19½ x W. 15 x D. 12 in. (49.5 x 38.1 x 30.5 cm) Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.205 Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society 3 4 Kamakura Realism and Spirituality in the Sculpture of Japan Art is of intrinsic importance to the educational process. The arts teach young people how to learn by inspiring in them the desire to learn. The arts use a symbolic language to convey the cultural values and ideologies of the time and place of their making. By including Asian arts in their curriculums, teachers can embark on culturally diverse studies and students will gain a broader and deeper understanding of the world in which they live. Often, this means that students will be encouraged to study the arts of their own cultural heritage and thereby gain self-esteem. Given that the study of Asia is required in many state curriculums, it is clear that our schools and teachers need support and resources to meet the demands and expectations that they already face. -

Fine Japanese and Korean Art I New York I March 20, 2019

Fine Japanese and Korean Art and Korean Fine Japanese I New York I March 20, 2019 I March I New York 25415 Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York I March 20, 2019 Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York | Wednesday March 20 2019, at 1pm BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Japanese Art Department Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Jeffrey Olson, Director +1 (212) 644 9001 bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6516 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax [email protected] PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit ILLUSTRATIONS www.bonhams.com/25415 Thursday March 14 Takako O’Grady, Front cover: Lot 247 10am to 5pm Administrator Inside front cover: Lot 289 Friday March 15 Please note that bids should be +1 (212) 461 6523 Back cover: Lot 390 10am to 5pm summited no later than 24hrs [email protected] Inside back cover: Lot 287 Saturday March 16 prior to the sale. New bidders 10am to 5pm must also provide proof of Sunday March 17 identity when submitting bids. REGISTRATION 10am to 5pm Failure to do this may result in IMPORTANT NOTICE your bid not being processed. Monday March 18 Please note that all customers, 10am to 5pm irrespective of any previous activity Tuesday March 19 LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS with Bonhams, are required to 10am to 3pm AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE complete the Bidder Registration Please email bids.us@bonhams. Form in advance of the sale. The SALE NUMBER: 25415 com with “Live bidding” in form can be found at the back the subject line 48hrs before of every catalogue and on our the auction to register for this website at www.bonhams.com CATALOG: $35 service. -

Jomon Culture and the Emishi

Jomon Culture and the Emishi There had been speculation that many ethnic groups used to inhabit the islands during the Jomon period, roughly ten thousand years B.C. to about 300 B.C. (ending earlier depending on the region). What has been found confirms a much older hypothesis that there was basically one ethnic group, the Jomon, who resided on all the islands. The skeletal remains that date back before the Yayoi period, when the Japanese speakers began their expansion, have been of one dominant population group whether in Western Japan, the Tohoku or Hokkaido. The one cultural trait they shared was the type of pottery they produced marked by distinctive rope-like patterns called jomon doki that gave them their name. In the latest research it is found that the transformation of the Jomon population occurred gradually as the Yayoi population identified with the Japanese speakers spread from northern Kyushu eastwards. Intermixing of the populations was widespread as intermediate skeletal types emerge in areas where the two populations came in contact with each other. However, over time, where these contacts occurred the Jomon population gradually changed to become more Yayoi in character indicating that the Yayoi began to outnumber the local Jomon population. Thus, the intermixing was heavily weighted towards the Yayoi population during the historical period particularly in western Japan since the Jomon people there were not as numerous. One exception is in the southern Kyushu areas dominated by the Kumaso during ancient times. To this day the area around present-day Kagoshima has a population that is relatively unchanged since the Jomon, and have characteristics that are more related to the Ainu and Okinawans than to modern Japanese. -

Social Conformity and Nationalism in Japan

SOCIAL CONFORMITY AND NATIONALISM IN JAPAN by Chie Muroga Jex B.A., The University of West Florida, 2005 A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Anthropology 2009 The thesis of Chie Muroga Jex is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ Rosalind A. Fisher, M.A., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Terry J. Prewitt, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Robert C. Philen, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ John R. Bratten, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean of Graduate Studies Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deep appreciation to Dr. Terry J. Prewitt, Dr. Robert Philen, and Ms. Rosalind Fisher for their willingness to be my thesis committee members. My fellow anthropology graduate student, Trey Bond, also gave me many helpful suggestions. They have inspired and sustained me with insightful comments, patience and encouragement. I also wish to especially thank my bilingual husband, Timothy T. Jex for always taking time, and patiently proofreading and correcting my English grammar despite his busy schedule. Without these professional and generous supporters,