Chapter 12 Seafaring and the Development of Cultural Complexity in Northeast Asia: Evidence from the Japanese Archipelago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OAR Strategy (2020-2026)

OAR Strategy 2020-2026 Deliver NOAA’s Future OAR Strategic Plan | 1 2 | OAR Strategic Plan Contents 4 Introduction 5 Vision and Mission 5 Values 6 Organization 8 OAR’s Changing Operating Landscape 10 Strategic Approach 13 Goals and Objectives 14 Explore the Marine Environment 15 Detect Changes in the Ocean and Atmosphere 16 Make Forecasts Better 17 Drive Innovative Science 18 Appendix I: Strategic Mapping 19 Appendix II: Congressional Mandates OAR Strategic Plan | 3 Introduction Introduction — A Message from Craig McLean Message from Craig McLean The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was created to include a major Line Office, Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR), focused on determining the relationship between the atmosphere and the ocean. That task has been at the core of OAR’s work for the past half century, performed by federal and academic scientists and in the proud company of our other Line Offices of NOAA. Principally a research organization, OAR has contributed soundly to NOAA’s reputation as being among the finest government science agencies worldwide. Our work is actively improving daily weather forecasts and severe storm warnings, furthering public understanding of our climate future and the global role of the ocean, and helping create more resilient communities for a sound economy. Our research advances products and services that protect lives and livelihoods, the economy, and the environment. The research landscape of tomorrow will be different from that of today. There will likely be additional contributors to the sciences we study, including more involvement from the private sector, increased philanthropic participation, and greater academic integration. -

Oar Manual(PDF)

TABLE OF CONTENTS OAR ASSEMBLY IMPORTANT INFORMATION 2 & USE MANUAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS 3 ASSEMBLY Checking the Overall Length of your Oars .......................4 Setting Your Adjustable Handles .......................................4 Setting Proper Oar Length ................................................5 Collar – Installing and Positioning .....................................5 Visit concept2.com RIGGING INFORMATION for the latest updates Setting Inboard: and product information. on Sculls .......................................................................6 on Sweeps ...................................................................6 Putting the Oars in the Boat .............................................7 Oarlocks ............................................................................7 C.L.A.M.s ..........................................................................7 General Rigging Concepts ................................................8 Common Ranges for Rigging Settings .............................9 Checking Pitch ..................................................................10 MAINTENANCE General Care .....................................................................11 Sleeve and Collar Care ......................................................11 Handle and Grip Care ........................................................11 Evaluation of Damage .......................................................12 Painting Your Blades .........................................................13 ALSO AVAILABLE FROM -

OAR 437, Division 2, Subdivision Z, Asbestos

Oregon Administrative Rules Oregon Occupational Safety and Health Division ASBESTOS Z OAR 437, DIVISION 2 GENERAL OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH RULES SUBDIVISION Z – TOXIC AND HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES 437-002-0360 Adoption by Reference. In addition to, and not in lieu of, any other safety and health codes contained in OAR Chapter 437, the Department adopts by reference the following federal regulations printed as part of the Code of Federal Regulations, 29 CFR 1910, in the Federal Register: (2) 29 CFR 1910.1001 Asbestos, published 3/26/12, FR vol. 77, no. 58, p. 17574. These standards are on file at the Oregon Occupational Safety and Health Division, Oregon Department of Consumer and Business Services, and the United States Government Printing Office. Stat. Auth.: ORS 654.025(2) and 656.726(4). Stats. Implemented: ORS 654.001 through 654.295. Hist: APD Admin. Order 13-1988, f. 8/2/88, ef. 8/2/88 (Benzene). APD Admin. Order 14-1988, f. 9/12/88, ef. 9/12/88 (Formaldehyde). APD Admin. Order 18-1988, f. 11/17/88, ef. 11/17/88 (Ethylene Oxide). APD Admin. Order 4-1989, f. 3/31/89, ef. 5/1/89 (Asbestos-Temp). APD Admin. Order 6-1989, f. 4/20/89, ef. 5/1/89 (Non-Asbestiforms-Temp). APD Admin. Order 9-1989, f. 7/7/89, ef. 7/7/89 (Asbestos & Non-Asbestiforms-Perm). APD Admin. Order 11-1989, f. 7/14/89, ef. 8/14/89 (Lead). APD Admin. Order 13-1989, f. 7/17/89, ef. 7/17/89 (Air Contaminants). -

Jomon: 11Th to 3Rd Century BCE Yayoi

Outline Lecture Sixteen—Early Japanese Mythology and Shinto Ethics General Chronology: Jomon: 11th to 3rd century B.C.E. Yayoi: 3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E. Tomb: 3rd to 6th C.E. Yamato: 6th to 7th C.E. I) Prehistoric Origins a) Early Japanese history shrouded in obscurity i) Writing did not develop in Japan until 6th century C.E. ii) No remains of cities or other large scale settlements iii) Theories of origins of earliest settlers b) Jomon (Roughly 11th to 3rd century B.C.E.) i) “Rope-pattern” pottery ii) Hunter-gathering settlements iii) Lack of social stratification? c) Yayoi (3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E.) i) Simultaneous introduction of irrigation, bronze, and iron contributing to revolutionary changes (1) Impact of change in continental civilizations tend to be more gradual (2) In Japan, effect of changes are more dramatic due to its isolation (a) Foreign elements trickle in, then blend with indigenous elements (b) Creating a distinctive synthesis in “petri-dish” (pea-tree) environment ii) Increasing signs of specialization and social stratification (1) Objects of art—less primitive, more self-conscious (2) Late Yayoi burial practices d) Tomb or Kofun Period (3rd to 7th) i) Large and extravagant tombs in modern day Osaka ii) What beliefs about the afterlife do they reflect? (1) Two strains in Japanese religious cosmology iii) Emergence of a powerful mounted warrior class iv) Regional aristocracies each with its clan name (1) Uji vs. Be (2) Dramatic increase in social stratification e) Yamato State (6th to 8th C.E.) II) Yamato’s Constructions -

Ceramics Monthly Mar93 Cei03

William Hunt..................................... Editor Ruth C. Butler................. Associate Editor Robert L. Creager...................... Art Director Kim Nagorski..................Assistant Editor Mary Rushley................ Circulation Manager MaryE. Beaver ....Assistant Circulation Manager Connie Belcher.........Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis............................Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448 Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Profes sional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Bou levard, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, announcements, news releases, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations and digital TIFF images are welcome and will be considered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines: A book let describing standards and procedures for sub mitting materials is available upon request. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) index ing is available through Wilsonline, 950 Univer sity Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Company, 362 Lakeside Drive, Forest City, California 94404. -

Preliminary Program Draft (March

NEAA Preliminary Program as of 24 March 2015 Poster Session – Saturday all Day (Poster) Priscilla H. Montalto (Skidmore College) Archaeological Methods of Recovery at the Sucker Brook Site [email protected] (Poster) Jake DeNicola (Skidmore College) The Stigmatization of Postindustrial Urban Landscapes and Communities in Upstate, New York [email protected] (Poster) Rebecca Morofsky (Skidmore College) The Stigmatization of Postindustrial Urban Landscapes and Communities in Upstate, New York [email protected] (Poster) Rachel Tirrell, Senior Author, (Franklin Pierce University), Courtney Cummings, Kelsey Devlin, Brian Kirn, Cooper Leatherwood, Rebecca Nystrom, Katherine Pontbriand, (all from Franklin Pierce University) [email protected] (Poster) Ammie Mitchell (Buffalo University) Ceramic Petrography and Color Symbolism in Northeastern Archaeology [email protected] (Poster) Kate Pontbriand (Franklin Pierce University) The History of Tranquility Farm [email protected] Saturday Morning 9-11 Northeastern Anthropology Panel Chairs: Kelsey Devlin & Cory Atkinson Grace Belo (Bridgewater State University) A Walk Through Time with the Boats Archaeological Site of Dighton Massachusetts Cory Atkinson (SUNY Binghamton) A Preliminary Analysis of Paleoindian Spurred End Scrapers from the Corditaipe Site in Central New York [email protected] Kimberly H. Snow (Skidmore College) Ceramic Wall Thinning at Fish Creek-Saratoga Lake During the Late Woodland Period [email protected] Gail R. Golec (Monadnock Archaeological Consulting, LLC.) Folklore versus Forensics: how the historical legend of one NH town held up to modern scientific scrutiny [email protected] Kelsey Devlin (Franklin Pierce University) Just Below the Surface: Historic and Archaeological Analysis of Submerged Sites in Lake Winnipesaukee [email protected] John M. Fable, William A. Farley, and M. -

Artful Adventures JAPAN an Interactive Guide for Families 56

Artful Adventures JAPAN An interactive guide for families 56 Your Japanese Adventure Awaits You! f See inside for details JAPAN Japan is a country located on the other side of the world from the United States. It is a group of islands, called an archipelago. Japan is a very old country and the Japanese people have been making beautiful artwork for thousands of years. Today we are going to look at ancient objects from Japan as well as more recent works of Japanese art. Go down the stairs to the lower level of the Museum. At the bottom of the steps, turn left and walk through the Chinese gallery to the Japanese gallery. Find a clay pot with swirling patterns on it (see picture to the left). This pot was made between 2,500 and 1,000 b.c., during the Late Jōmon period—it is between 3,000 and 4,500 years old! The people who lived in Japan at this time were hunter-gatherers, which means that they hunted wild animals and gathered roots and plants for food. The Jomon people started forming small communities, and began to make objects that were both beautiful and useful— like this pot which is decorated with an interesting pattern and was used for storage. Take a close look at the designs on this pot. Can you think of some words to describe these designs? Japanese, Middle to Late Jōmon period, ca. 3500–ca. 1000 B.C.: jar. Earthenware, h. 26.0 cm. 1. ............................................................................................................. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund (2002-297). -

Matrix: a Journal for Matricultural Studies “In the Beginning, Woman

Volume 02, Issue 1 March 2021 Pg. 13-33 Matrix: A Journal for Matricultural Studies M https://www.networkonculture.ca/activities/matrix “In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun”: Takamure Itsue’s Historical Reconstructions as Matricultural Explorations YASUKO SATO, PhD Abstract Takamure Itsue (1894-1964), the most distinguished pioneer of feminist historiography in Japan, identified Japan’s antiquity as a matricultural society with the use of the phrase ‘women-centered culture’ (josei chūshin no bunka). The ancient classics of Japan informed her about the maternalistic values embodied in matrilocal residence patterns, and in women’s beauty, intelligence, and radiance. Her scholarship provided the first strictly empirical verification of the famous line from Hiratsuka Raichō (1886-1971), “In the beginning, woman was the sun.” Takamure recognized matricentric structures as the socioeconomic conditions necessary for women to express their inner genius, participate fully in public life, and live like goddesses. This paper explores Takamure’s reconstruction of the marriage rules of ancient Japanese society and her pursuit of the underlying principles of matriculture. Like Hiratsuka, Takamure was a maternalist feminist who advocated the centrality of women’s identity as mothers in feminist struggles and upheld maternal empowerment as the ultimate basis of women’s empowerment. This epochal insight into the ‘woman question’ merits serious analytic attention because the principle of formal equality still visibly disadvantages women with children. Keywords Japanese women, Ancient Japan, matriculture, Takamure Itsue, Hiratsuka Raicho ***** Takamure Itsue (1894-1964), pionière éminente de l'historiographie feministe au Japon, a découvert dans l'antiquité japonaise une société matricuturelle qu'elle a identifiée comme: une 'société centrée sur les femmes' (josei chūshin no bunka) ou société gynocentrique. -

The Distribution of Obsidian in the Eastern Mediterranean As Indication of Early Seafaring Practices in the Area a Thesis B

The Distribution Of Obsidian In The Eastern Mediterranean As Indication Of Early Seafaring Practices In The Area A Thesis By Niki Chartzoulaki Maritime Archaeology Programme University of Southern Denmark MASTER OF ARTS November 2013 1 Στον Γιώργο 2 Acknowledgments This paper represents the official completion of a circle, I hope successfully, definitely constructively. The writing of a Master Thesis turned out that there is not an easy task at all. Right from the beginning with the effort to find the appropriate topic for your thesis until the completion stage and the time of delivery, you got to manage with multiple issues regarding the integrated presentation of your topic while all the time and until the last minute you are constantly wondering if you handled correctly and whether you should have done this or not to do it the other. So, I hope this Master this to fulfill the requirements of the topic as best as possible. I am grateful to my Supervisor Professor, Thijs Maarleveld who directed me and advised me during the writing of this Master Thesis. His help, his support and his invaluable insight throughout the entire process were valuable parameters for the completion of this paper. I would like to thank my Professor from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Nikolaos Efstratiou who help me to find this topic and for his general help. Also the Professor of University of Crete, Katerina Kopaka, who she willingly provide me with all of her publications –and those that were not yet have been published- regarding her research in the island of Gavdos. -

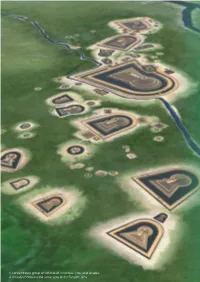

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Fire Season Requirements for Industrial Operations

FIRE SEASON REQUIREMENTS The following fire season requirements become effective when fire season is declared in each Oregon Department of Forestry Fire Protection District, including those protected by associations (DFPA, CFPA, WRPA). NO SMOKING (477.510) No smoking while working or traveling in an operation area. HAND TOOLS (ORS 477.655, OAR 629-43-0025) Supply hand tools for each operation site - 1 tool per person with a mix of pulaskis, axes, shovels, hazel hoes. Store all hand tools for fire in a sturdy box clearly identified as containing firefighting tools. Supply at least oneor boxf each operation area. Crews of 4 or less are not required to have a fire tools box as long as each person has a shovel, suitable for fire-fighting and available for immediate use while working on the operation. FIRE EXTINGUISHERS (ORS 477.655, OAR 629-43-0025) Each internal combustion engine used in an operation, except power saws, shall be equipped with a chemical fire extinguisher rated as not less than 2A:10BC (5 pound). POWER SAWS ( ORS 477.640, OAR 629-043-0036) Power saws must meet Spark Arrester Guide specifications - a stock exhaust system and screen with < .023 inch holes. The following shall be immediately available for prevention and suppression of fire: One gallon of water or pressurized container of fire suppressant of at least eight ounce capacity 1 round pointed shovel at least 8 inches wide with a handle at least 26 inches long The power saw must be moved at least 20' from the place of fueling before it is started. -

Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1992 19/2-3 Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period I s h in o H ironobu 石野博信 The rituals of the Kofun period were closely connected with both daily life and political affairs. The chieftain presided over the principal rites, whether in the mountains, on the rivers, or along the roadsides. The chieftain’s funeral was the preeminent rite, with a tomb mound, or kofun, constructed as its finale. The many and varied kofun rituals have been discussed elsewhere;1 here I shall concentrate on other kami rites and their departure from Yayoi practices. A Ritual Revolution Around AD 190, following a period of warfare called the “Wa Unrest,” the overall leadership of Wa was assumed by Himiko [Pimiko], female ruler of the petty kingdom of Yamatai. Beginning in 239 she opened diplomatic relations with the Wei court in China as the monarch of Wa, and she died around 248. Makimuku 1 type pottery appeared around 190; in 220 or so it was followed by Makimuku 2,and then by Makimuku 3, in about 250. The 92-meter-long keyhole-shaped Makimuku Ishizuka tomb in Sakurai City, Nara, was constructed in the first half of the third century; in the latter half of the same century the Hashihaka tomb was built. Hence the reign of Himiko, circa 190 to 248,corresponds to the appearance of key hole-shaped tombs. It was the dawn of the Kofun period and a formative time in Kofun-period ritual. In the Initial Kofun, by which I mean the period traditionally assigned to the very end of the Yayoi, bronze ritual objects were smashed, dis * This article is a partial translation of the introductory essay to volume 3 of Ish in o et al.