Infrastructure Is Not Enough: Interactions Between the Environment, Socioeconomic Disadvantage, and Cycling Participation in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

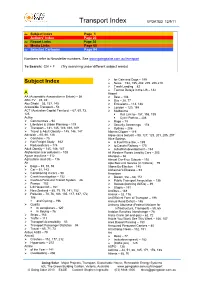

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

TAG A4 Document

Transport Priorities Contents Page What is the Eastern Transport Coalition? 3 Investing in the East is investing in Victoria 4 P r iorities 5 Projects Train and Tram 7 - 14 Bus 15 - 19 Roads 20 - 24 Walking and Cycling 25 - 31 What’s next? 32 Version 1 What is the Eastern Transport Coalition? The Eastern Transport Coalition (ETC) consists of Melbourne’s seven eastern metropolitan councils: City of Greater Dandenong, Knox City Council, Manningham City Council, Maroondah City Council, City of Monash, City of Whitehorse and Yarra Ranges Shire Council. The ETC advocates for sustainable and integrated transport services to reduce the level of car dependency so as to secure the economic, social and environmental wellbeing of Melbourne’s east. We aim to work in The Eastern Transport Coalition has put partnership with federal and state together a suite of projects and governments to ensure the future priorities to promote connectivity, sustainability of Melbourne’s eastern region. In liveability, sustainability, productivity order to preserve the region’s economic and eciency throughout Melbourne’s promise and ensure the wellbeing of our residents, it is crucial that we work to promote eastern region. The ETC is now better transport options in the east. advocating for the adoption and implementation of each of the transport priorities proposed in this document by Vision for the East the Federal and State Government. The ETC aims for Melbourne’s east to become Australia’s most liveable urban region connected by world class transport linkages, ensuring the sustainability and economic growth of Melbourne. With better transport solutions, Melbourne’s east will stay the region where people build the best future for themselves, their families, and their businesses. -

Quantifying Spatial Variation in Interest in Bike Riding

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.14.21253340; this version posted May 11, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 The potential for bike riding across entire cities: quantifying spatial variation in interest in bike riding 2 Lauren K Pearsona, Joanna Dipnalla,b, Belinda Gabbea,c, Sandy Braafa, Shelley Whitec, Melissa Backhousec, Ben Becka 3 Keywords: Cycling, active transport, bike riding, health promotion 4 a) School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Victoria, Australia 5 b) School of Medicine, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, Australia 6 c) Health Data Research UK, Swansea University, Swansea, United Kingdom 7 d) VicHealth, Victoria, Australia 8 9 ABSTRACT 10 Background: Riding a bike is beneficial for health, the environment and for reducing traffic congestion. Despite this, bike 11 riding participation in the state of Victoria, Australia, is low. To inform planning and practice, there is a need to understand 12 the proportion of the population (the ‘near-market’) that are interested in riding a bike, and how this varies across regions. 13 The Geller typology classifies individuals into one of four groups, based on their confidence to ride a bike in various 14 infrastructure types, and frequency of bike riding. The typology has been used at a city, state and country-wide scale, 15 however not at a smaller spatial scale. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Transport Strategy Refresh Participate Melbourne Community Engagement Analysis

Transport Strategy Refresh Participate Melbourne Community Engagement Analysis Project no. 28861 Date: 26 September 2018 © 2018 Ernst & Young. All Rights Reserved. Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation Page 1 28861 – City of Melbourne – Transport Strategy Refresh report – September 26, 2018 EY Sweeney (a trading name of Ernst & Young) ("Consultant") was engaged on the instructions of City of 9. No claim or demand or any actions or proceedings may be brought against the Consultant arising from or Melbourne ("Client") to produce this community consultation report ("Project"), in accordance with the terms connected with the contents of the Report or the provision of the Report to any recipient. The Consultant and conditions found in the “28861 Transport Strategy Refresh Proposal” dated 6 August 2018. will be released and forever discharged from any such claims, demands, actions or proceedings. 10. To the fullest extent permitted by law, the recipient of the Report shall be liable for all claims, demands, The results of the Consultant’s work, including the assumptions and qualifications made in preparing the report, actions, proceedings, costs, expenses, loss, damage and liability made against or brought against or are set out in the Consultant's report dated 26 September 2018 ("Report"). You should read the Report in its incurred by the Consultant arising from or connected with the Report, the contents of the Report or the entirety including any disclaimers and attachments. A reference to the Report includes any part of the Report. provision of the Report to the recipient. No further work has been undertaken by the Consultant since the date of the Report to update it. -

This May Be the Author's Version of a Work That Was Submitted/Accepted

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Heesch, Kristiann & Sahlqvist, Shannon (2013) Key influences on motivations for utility cycling (cycling for transport to and from places). Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 24(3), pp. 227-233. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/64599/ c Copyright 2013 CSIRO This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE13062 RUNNING HEAD: Motivations for Utility Cycling Key influences on motivations for utility cycling (cycling for transport to and from places) 1 Abstract Issue addressed: Although increases in cycling in Brisbane are encouraging, bicycle mode share to work in the state of Queensland remains low. -

Cycling Futures the High-Quality Paperback Edition of This Book Is Available for Purchase Online

Cycling Futures The high-quality paperback edition of this book is available for purchase online: https://shop.adelaide.edu.au/ Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press The University of Adelaide South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes externally refereed scholarly books by staff of the University of Adelaide. It aims to maximise access to the University’s best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2015 The authors This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. For the full Cataloguing-in-Publication data please contact the National Library of Australia: [email protected] ISBN (paperback) 978-1-925261-16-5 ISBN (pdf) 978-1-925261-17-2 ISBN (epub) 978-1-925261-18-9 ISBN (kindle) 978-1-925261-19-6 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20851/cycling-futures Editor: Rebecca Burton Editorial Support: Julia Keller Book design: Midland Typesetters Pty Ltd Cover design: Emma Spoehr Cover image: Courtesy of Takver, licensed under a Creative Commons ShareAlike 2.0., https://www.flickr.com/photos/81043308@N00/4038650169 Paperback printed by Griffin Press, South Australia Contents Page Preface vii Editors ix Contributors xi PART I Current challenges 1. -

Pioneer Valley Regional Bike Share System Pilot

Pioneer Valley Regional Bike Share System Pilot Pioneer Valley Regional Bike Share System Pilot April 2016 Alta Planning + Design | Page 0 Pioneer Valley Regional Bike Share System Pilot Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Business Models ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Overview .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2.2 Business Model Matrix ................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Proposed Business Model............................................................................................................................................. 7 3. System Costs and Revenues .................................................................................................................................................. 9 3.1 Cost Components ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Sport and Recreation Strategy Background Report

SPORT AND RECREATION STRATEGY BACKGROUND REPORT ‘Getting Our Community APagective’ 1 of 166 About this document The City of Port Phillip’s Sport and Recreation Strategy 2015-24 provides a framework which achieves our objective of developing a shared vision for Council and the community, to guide the provision of facilities and services to meet the needs of the Port Phillip community over the next ten years. The documents prepared for this strategy are: Volume 1. Sport and Recreation Strategy 2015-24 This document outlines the key strategic directions that the organisation will work towards to guide the current and future provision of facilities and services to meet the needs of the Port Phillip community over the next ten years. Volume 2. Getting Our Community Active – Sport and Recreation Strategy 2015-24: Implementation Plan This document details the Actions and Tasks and the associated Key Performance Indicators KPI’s required to achieve Council’s defined Goals and Outcomes. Volume 3. Sport and Recreation Strategy 2015-24: Background Report This document presents the relevant literature that has been reviewed, an assessment of the potential demand for sport and recreation in Port Phillip, analysis of the current supply of sport and recreation opportunities in Port Phillip, and outlines the findings from consultation with sports clubs, peak bodies, schools and the community. *It is important to note that this document attempts to display the most current information available at the time of production. As a result, there are some minor inconsistencies in the presentation of some data due to the lack of available updated information. -

Cycling to Work: Not Only a Utilitarian Movement but Also an Embodiment of Meanings and Experiences That Constitute Crucial

Conclusion This research analysed the different facets of utility cycling in Switzerland, using the example of commuting. We took as our starting point the concept of the cycling system, or velomobility, which underlines the importance of taking into account all elements—not only material and technical but also social, political and symbolic— which influence this practice. From this perspective, we argued that cycling—in terms of volume, frequency, distance, motivation, etc.—depends on the coming together of two potentials. The first of these is motility [11–13] or, more precisely, the indi- viduals’ cycling potential. It is built around access (‘to be able to’ use a means of transport), skills ((‘to know how to’ cycle for utility reasons) and appropriation (‘to want to’ cycle). Individuals’ appropriation of cycling depends on their perception of that mode and of its particularities, which can be interpreted as a confluence of three fundamental dimensions of mobility: movement, meaning and experience in a context of power in regards to the dominant system of automobility [6]. The second of the two potentials is the territory’s hosting potential, or its degree of bikeability, which relates to the spatial context, the available infrastructure and amenities (bicycle urbanism), as well as social and legal norms and rules. In order to identify a large sample of bicycle commuters, we focused on the bike to work scheme, which each year brings together people who commit to cycling to their place of work as often as possible during the months of May and/or June. Nearly 14,000 people completed an online questionnaire addressing the dimensions of velomobility. -

Newsletter July 2008

Newsletter July 2008 Boroondara BUG meetings are held on the 2nd Wednesday of each month, except January. The Next meeting will be at 7.30pm on Wednesday 9th July, at the Swinburne Hawthorn Campus in room TD244. The TD building is between Park and Wakefield Streets. All welcome. The Boroondara BUG is a voluntary group working to promote the adoption of a safe and practical environment for utility and recreational cyclists in the City of Boroondara. We have close links with the City of Boroondara, Bicycle Victoria, Bicycle Federation of Australia and other local Bicycle Users’ Groups. Boroondara BUG has a website at http://www.boroondarabug.org that contains interesting material related to cycling, links to other cycle groups, recent Boroondara BUG Newsletters and breaking news. We also have two Yahoo Groups: 1. Send a blank email to: [email protected] to receive notification when the latest monthly newsletter and rides supplement have been placed on the web site and very occasional important messages. 2. Send a blank email to: [email protected] to monitor or join in an ongoing discussion of bike related issues both local and general. All articles in this newsletter are the views and opinions of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of any other members of Boroondara BUG. All rides publicised in this newsletter are embarked upon at your own risk. Trail Notes Gardiners Creek Trail Detour Still no word on this unfortunately. Darebin Creek Path Missing Link to be closed Work is well underway on construction of an underpass, including a section of boardwalk, under Darebin Rd. -

What It's Like to Ride a Bike: Understanding Cyclist Experiences

Curtin University Sustainability Policy (CUSP) Institute What It’s Like to Ride a Bike: Understanding Cyclist Experiences Georgia Clare Scott This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University April 2018 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Human Ethics The research presented and reported in this thesis was conducted in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007) – updated March 2014. The proposed research study received human research ethics approval from the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (EC00262), Approval Number # HURGS-14-14. Georgia Clare Scott 23 April 2018 iii Abstract Sustainability research recognises the role transport plays in shaping cities, and the destructive consequences of automobile dependency. As a low carbon, affordable, healthy and efficient transport mode, cycling necessarily contributes towards making cities more liveable and sustainable. Research thus far, however, has failed to fully engage with the experiential aspect of mobility, missing a window into both the liveability of cities and the success or failure of the transport systems within them. In response, this thesis explores how people’s experiences cycling in urban environments can be understood and used to inform transport policy. Its objectives are to contribute better understandings of urban cycling mobilities, and how such understandings can inform Australian sustainable transport policy, by comparing Western cities of high and low cycling amenity through using a combination of semi-structured and go-along interviews.