What It's Like to Ride a Bike: Understanding Cyclist Experiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

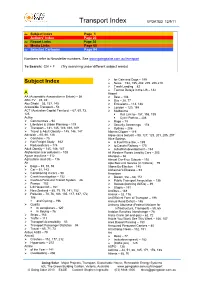

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

Marin County Bicycle Share Feasibility Study

Marin County Bicycle Share Feasibility Study PREPARED BY: Alta Planning + Design PREPARED FOR: The Transportation Authority of Marin (TAM) Transportation Authority of Marin (TAM) Bike Sharing Advisory Working Group Alisha Oloughlin, Marin County Bicycle Coalition Benjamin Berto, TAM Bicycle/Pedestrian Advisory Committee Representative Eric Lucan, TAM Board Commissioner Harvey Katz, TAM Bicycle/Pedestrian Advisory Committee Representative Stephanie Moulton-Peters, TAM Board Commissioner R. Scot Hunter, Former TAM Board Commissioner Staff Linda M. Jackson AICP, TAM Planning Manager Scott McDonald, TAM Associate Transportation Planner Consultants Michael G. Jones, MCP, Alta Planning + Design Principal-in-Charge Casey Hildreth, Alta Planning + Design Project Manager Funding for this study provided by Measure B (Vehicle Registration Fee), a program supported by Marin voters and managed by the Transportation Authority of Marin. i Marin County Bicycle Share Feasibility Study Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................................ ii 1 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. 1 2 Report Contents ................................................................................................................................................... 5 3 What is Bike Sharing? ........................................................................................................................................ -

TAG A4 Document

Transport Priorities Contents Page What is the Eastern Transport Coalition? 3 Investing in the East is investing in Victoria 4 P r iorities 5 Projects Train and Tram 7 - 14 Bus 15 - 19 Roads 20 - 24 Walking and Cycling 25 - 31 What’s next? 32 Version 1 What is the Eastern Transport Coalition? The Eastern Transport Coalition (ETC) consists of Melbourne’s seven eastern metropolitan councils: City of Greater Dandenong, Knox City Council, Manningham City Council, Maroondah City Council, City of Monash, City of Whitehorse and Yarra Ranges Shire Council. The ETC advocates for sustainable and integrated transport services to reduce the level of car dependency so as to secure the economic, social and environmental wellbeing of Melbourne’s east. We aim to work in The Eastern Transport Coalition has put partnership with federal and state together a suite of projects and governments to ensure the future priorities to promote connectivity, sustainability of Melbourne’s eastern region. In liveability, sustainability, productivity order to preserve the region’s economic and eciency throughout Melbourne’s promise and ensure the wellbeing of our residents, it is crucial that we work to promote eastern region. The ETC is now better transport options in the east. advocating for the adoption and implementation of each of the transport priorities proposed in this document by Vision for the East the Federal and State Government. The ETC aims for Melbourne’s east to become Australia’s most liveable urban region connected by world class transport linkages, ensuring the sustainability and economic growth of Melbourne. With better transport solutions, Melbourne’s east will stay the region where people build the best future for themselves, their families, and their businesses. -

Factors Influencing Bike Share Membership

Transportation Research Part A 71 (2015) 17–30 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part A journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tra Factors influencing bike share membership: An analysis of Melbourne and Brisbane ⇑ Elliot Fishman a, , Simon Washington b,1, Narelle Haworth c,2, Angela Watson c,3 a Department Human Geography and Spatial Planning, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Heidelberglaan 2, 3584 CS Utrecht, Netherlands b School of Urban Development, Faculty of Built Environment and Engineering and Centre for Accident Research and Road Safety (CARRS-Q), Faculty of Health Queensland University of Technology, 2 George St., GPO Box 2434, Brisbane, Qld 4001, Australia c Centre for Accident Research and Road Safety – Queensland, K Block, Queensland University of Technology, 130 Victoria Park Road, Kelvin Grove, QLD 4059, Australia article info abstract Article history: The number of bike share programs has increased rapidly in recent years and there are cur- Received 17 May 2013 rently over 700 programs in operation globally. Australia’s two bike share programs have Received in revised form 21 August 2014 been in operation since 2010 and have significantly lower usage rates compared to Europe, Accepted 29 October 2014 North America and China. This study sets out to understand and quantify the factors influ- encing bike share membership in Australia’s two bike share programs located in Mel- bourne and Brisbane. An online survey was administered to members of both programs Keywords: as well as a group with no known association with bike share. A logistic regression model Bicycle revealed several significant predictors of membership including reactions to mandatory CityCycle Bike share helmet legislation, riding activity over the previous month, and the degree to which conve- Melbourne Bike Share nience motivated private bike riding. -

The Advent of Sustainable Transport in Scotland: the Implementation of Glasgow’S Strategic Plans for Cycling and the Case of South City Way

Master thesis in Sustainable Development 2019/21 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling The advent of Sustainable Transport in Scotland: The implementation of Glasgow’s Strategic Plans for Cycling and the case of South City Way Georgi Gushlekov DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER Master thesis in Sustainable Development 2019/21 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling The advent of Sustainable Transport in Scotland: The implementation of Glasgow’s Strategic Plans for Cycling and the case of South City Way Georgi Gushlekov Supervisor: Stefan Gössling Subject Reviewer: Jan Henrik Nilsson Copyright © Georgi Gushlekov and the Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University Published at Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University (www.geo.uu.se), Uppsala, 2019 Contents Abstract Summary List of Figures List of Tables 1. Introduction 1.1. Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Purpose of the study. ......................................................................................................... 2 2. Theoretical Rationale ..................................................................................................................... 4 2.1. Urban Planning and sustainable development - a review ................................................. 4 2.1.1. Sustainable development within the sphere of urban planning ................................ 4 2.1.2. Sustainable development within the sphere of public engagement -

BIKE-SHARING SYSTEM DESIGN Guidelines on Conceiving and Implementing a BSS As a Public Transport with a Monocentric Heterogeneous Demand

BIKE-SHARING SYSTEM DESIGN Guidelines on conceiving and implementing a BSS as a public transport with a monocentric heterogeneous demand Author Guilherme Chalhoub Dourado Supervisor Francesc Soriguera Martí April 2018 BIKE-SHARING SYSTEM DESIGN Guidelines on conceiving and implementing a BSS as a public transport with a monocentric heterogeneous demand Author Guilherme Chalhoub Dourado Tutor Francesc Soriguera Martí Master Supply Chain Transportation in Mobility Emphasis in Transportation and Mobility This master thesis is submitted in satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Transportation Engineering Date April, 2018 i ii ABSTRACT Bike-Sharing Systems (BSS) are spreading over the world at a fast pace. Several reasons base the incentive from a government perspective, usually related to sustainability, healthy issues and general mobility. Although there was a great prioritization in the last years, literature on how to design and implement them are rather qualitative (e.g. guides and manuals) while technical research on the subject usually focus on extensive data inputs such as O/D matrixes and other methods that may not be robust nor extrapolated to other places. Also, lack of data in some regions make them of little use to be easily transferred. The thesis aims to work on an analytical continuum approach model to design a BSS, providing guidelines to a set of representative scenarios under the variation of the most important inputs. It is based on the optimization between Users and Agency, so there is a global outcome that minimizes total costs. In particular, it develops a monocentric approach to capture demand heterogeneity on cities center-peripheries. -

Quantifying Spatial Variation in Interest in Bike Riding

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.14.21253340; this version posted May 11, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 The potential for bike riding across entire cities: quantifying spatial variation in interest in bike riding 2 Lauren K Pearsona, Joanna Dipnalla,b, Belinda Gabbea,c, Sandy Braafa, Shelley Whitec, Melissa Backhousec, Ben Becka 3 Keywords: Cycling, active transport, bike riding, health promotion 4 a) School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Victoria, Australia 5 b) School of Medicine, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, Australia 6 c) Health Data Research UK, Swansea University, Swansea, United Kingdom 7 d) VicHealth, Victoria, Australia 8 9 ABSTRACT 10 Background: Riding a bike is beneficial for health, the environment and for reducing traffic congestion. Despite this, bike 11 riding participation in the state of Victoria, Australia, is low. To inform planning and practice, there is a need to understand 12 the proportion of the population (the ‘near-market’) that are interested in riding a bike, and how this varies across regions. 13 The Geller typology classifies individuals into one of four groups, based on their confidence to ride a bike in various 14 infrastructure types, and frequency of bike riding. The typology has been used at a city, state and country-wide scale, 15 however not at a smaller spatial scale. -

Bike Share's Impact on Car

Transportation Research Part D 31 (2014) 13–20 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part D journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/trd Bike share’s impact on car use: Evidence from the United States, Great Britain, and Australia ⇑ Elliot Fishman a, , Simon Washington b,1, Narelle Haworth c,2 a Healthy Urban Living, Department Human Geography and Spatial Planning, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Heidelberglaan 2, 3584 CS Utrecht, The Netherlands b Queensland Transport and Main Roads Chair School of Urban Development, Faculty of Built Environment and Engineering and Centre for Accident Research and Road Safety (CARRS-Q), Faculty of Health Queensland University of Technology, 2 George St GPO Box 2434, Brisbane, Qld 4001, Australia c Centre for Accident Research and Road Safety – Queensland, K Block, Queensland University of Technology, 130 Victoria Park Road, Kelvin Grove, Qld 4059, Australia article info abstract Keywords: There are currently more than 700 cities operating bike share programs. Purported benefits Bike share of bike share include flexible mobility, physical activity, reduced congestion, emissions and Car use fuel use. Implicit or explicit in the calculation of program benefits are assumptions City regarding the modes of travel replaced by bike share journeys. This paper examines the Bicycle degree to which car trips are replaced by bike share, through an examination of survey Sustainable and trip data from bike share programs in Melbourne, Brisbane, Washington, D.C., London, Transport and Minneapolis/St. Paul. A secondary and unique component of this analysis examines motor vehicle support services required for bike share fleet rebalancing and maintenance. These two components are then combined to estimate bike share’s overall contribution to changes in vehicle kilometers traveled. -

City of Casey Sport Cycling Strategy Final Report June 2014

City of Casey Sport Cycling Strategy Final Report June 2014 ŽƌĞŶŐĂůŽŶƐƵůƟŶŐ PO Box 260 Carnegie VIC 3165 City of Casey – Sports Cycling Strategy CONTENTS 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Project Background ..................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Project Aims and Objectives ....................................................................................... 4 1.3 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Cycling Definitions....................................................................................................... 5 2*5*2 )**************************************************************************************************************************6 2*5*3 #)**************************************************************************************************************************6 2*5*4 ,) % # $$-*****************************************************************************************************7 2*5*5 &%********************************************************************************************************************7 2*5*6 ) +# $$****************************************************************************************************************************7 2*5*7 & (#$*****************************************************************************************************7 2 Social -

Transport Strategy Refresh Participate Melbourne Community Engagement Analysis

Transport Strategy Refresh Participate Melbourne Community Engagement Analysis Project no. 28861 Date: 26 September 2018 © 2018 Ernst & Young. All Rights Reserved. Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation Page 1 28861 – City of Melbourne – Transport Strategy Refresh report – September 26, 2018 EY Sweeney (a trading name of Ernst & Young) ("Consultant") was engaged on the instructions of City of 9. No claim or demand or any actions or proceedings may be brought against the Consultant arising from or Melbourne ("Client") to produce this community consultation report ("Project"), in accordance with the terms connected with the contents of the Report or the provision of the Report to any recipient. The Consultant and conditions found in the “28861 Transport Strategy Refresh Proposal” dated 6 August 2018. will be released and forever discharged from any such claims, demands, actions or proceedings. 10. To the fullest extent permitted by law, the recipient of the Report shall be liable for all claims, demands, The results of the Consultant’s work, including the assumptions and qualifications made in preparing the report, actions, proceedings, costs, expenses, loss, damage and liability made against or brought against or are set out in the Consultant's report dated 26 September 2018 ("Report"). You should read the Report in its incurred by the Consultant arising from or connected with the Report, the contents of the Report or the entirety including any disclaimers and attachments. A reference to the Report includes any part of the Report. provision of the Report to the recipient. No further work has been undertaken by the Consultant since the date of the Report to update it. -

Cycling Futures the High-Quality Paperback Edition of This Book Is Available for Purchase Online

Cycling Futures The high-quality paperback edition of this book is available for purchase online: https://shop.adelaide.edu.au/ Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press The University of Adelaide South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes externally refereed scholarly books by staff of the University of Adelaide. It aims to maximise access to the University’s best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2015 The authors This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. For the full Cataloguing-in-Publication data please contact the National Library of Australia: [email protected] ISBN (paperback) 978-1-925261-16-5 ISBN (pdf) 978-1-925261-17-2 ISBN (epub) 978-1-925261-18-9 ISBN (kindle) 978-1-925261-19-6 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20851/cycling-futures Editor: Rebecca Burton Editorial Support: Julia Keller Book design: Midland Typesetters Pty Ltd Cover design: Emma Spoehr Cover image: Courtesy of Takver, licensed under a Creative Commons ShareAlike 2.0., https://www.flickr.com/photos/81043308@N00/4038650169 Paperback printed by Griffin Press, South Australia Contents Page Preface vii Editors ix Contributors xi PART I Current challenges 1. -

Safe and Viable Cycling in the Perth Metropolitan Area

Western Australian Auditor General’s Report Safe and Viable Cycling in the Perth Metropolitan Area Report 22: October 2015 Office of the Auditor General Western Australia 7th Floor Albert Facey House 469 Wellington Street, Perth Mail to: Perth BC, PO Box 8489 PERTH WA 6849 T: 08 6557 7500 F: 08 6557 7600 E: [email protected] W: www.audit.wa.gov.au National Relay Service TTY: 13 36 77 (to assist people with hearing and voice impairment) On request, we can deliver this report in an alternative format for those with visual impairment. © 2015 Office of the Auditor General Western Australia. All rights reserved. This material may be reproduced in whole or in part provided the source is acknowledged. ISSN: 2200-1913 (Print) ISSN: 2200-1921 (Online) WESTERN AUSTRALIAN AUDITOR GENERAL’S REPORT Safe and Viable Cycling in the Perth Metropolitan Area Report 22 October 2015 THE PRESIDENT THE SPEAKER LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY SAFE AND VIABLE CYCLING IN THE PERTH METROPOLITAN AREA This report has been prepared for submission to Parliament under the provisions of section 25 of the Auditor General Act 2006. Performance audits are an integral part of the overall audit program. They seek to provide Parliament with assessments of the effectiveness and efficiency of public sector programs and activities, and identify opportunities for improved performance. This audit looked at whether there is suitable infrastructure and support to ensure cycling is a safe and viable mode of transport in the Perth metropolitan area. My report finds that government has gradually improved cycling infrastructure in the Perth metropolitan area.