Transport Strategy 2030 Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moving Freight 2019 “Towards a 20 Year State Infrastructure Strategy”

South Australia’s Freight Transport Infrastructure Moving Freight 2019 “Towards a 20 Year State Infrastructure Strategy” July 2019 South Australian Freight Council Inc Level 1, 296 St Vincent Street Port Adelaide SA 5015 Tel.: (08) 8447 0664 Email: [email protected] www.safreightcouncil.com.au The South Australian Freight Council Inc is the State’s peak multi-modal freight and logistics industry group that advises all levels of government on industry related issues. SAFC represents road, rail, sea and air freight modes and operations, Freight service users (customers) and assists the industry on issues relating to freight and logistics across all modes. Disclaimer: While the South Australian Freight Council has used its best endeavours to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this report, much of the information provided has been sourced from third parties. Accordingly, SAFC accepts no liability resulting from the accuracy, interpretation, analysis or use of information provided in this report. In particular, infrastructure projects and proposals are regularly adjusted and amended, and those contained in this document, whilst accurate when sourced, may have changed and/or been amended. Contents Chairman’s Message Page 02 Executive Summary Page 03 Introduction Page 05 Core Infrastructure Principles / Policy Issues Page 08 Core Infrastructure Criteria Page 09 Overarching Strategy Needs and Integration Page 10 Protecting Freight Capability – A Public Asset Page 12 SAFC Priority Projects Page 14 Urgent Projects Page -

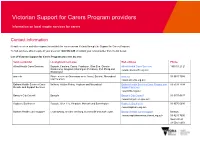

Victorian Support for Carers Program Providers

Victorian Support for Carers Program providers Information on local respite services for carers Contact information Respite services and other support is available for carers across Victoria through the Support for Carers Program. To find out more about respite in your area call 1800 514 845 or contact your local provider from the list below. List of Victorian Support for Carers Program providers by area Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Alfred Health Carer Services Bayside, Cardinia, Casey, Frankston, Glen Eira, Greater Alfred Health Carer Services 1800 51 21 21 Dandenong, Kingston, Mornington Peninsula, Port Phillip and <www.carersouth.org.au> Stonnington annecto Phone service in Grampians area: Ararat, Ballarat, Moorabool annecto 03 9687 7066 and Horsham <www.annecto.org.au> Ballarat Health Services Carer Ballarat, Golden Plains, Hepburn and Moorabool Ballarat Health Services Carer Respite and 03 5333 7104 Respite and Support Services Support Services <www.bhs.org.au> Banyule City Council Banyule Banyule City Council 03 9457-9837 <www.banyule.vic.gov.au> Baptcare Southaven Bayside, Glen Eira, Kingston, Monash and Stonnington Baptcare Southaven 03 9576 6600 <www.baptcare.org.au> Barwon Health Carer Support Colac-Otway, Greater Geelong, Queenscliff and Surf Coast Barwon Health Carer Support Barwon: <www.respitebarwonsouthwest.org.au> 03 4215 7600 South West: 03 5564 6054 Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Bass Coast Shire Council Bass Coast Bass Coast Shire Council 1300 226 278 <www.basscoast.vic.gov.au> -

CITY of MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners

CITY OF MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners The City of Melbourne respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) people of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. For the Kulin Nation, Melbourne has always been an important meeting place for events of social, educational, sporting and cultural significance. Today we are proud to say that Melbourne is a significant gathering place for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. melbourne.vic.gov.au CONTENTS Foreword 04 Context 05 Melbourne, a city that can’t stand still 05 How to thrive in a world of change 05 Our roadmap to a bold, inspirational future 05 Why creativity? Work, wandering and wellbeing 06 Case Studies 07 Düsseldorf Metro, Germany, 2016 09 Te Oro, New Zealand, 2015 11 Neighbour Doorknob Hanger 13 The Strategy 14 Appendices 16 Measuring creativity 17 How Melburnians contributed to this strategy 18 Melbourne’s Creative Strategy on a page 19 September 2018 Cover Image: SIBLING, Over Obelisk, part of Biennial Lab 2016. Photo by Bryony Jackson Image on left: Image: Circle by Naretha Williams performed at YIRRAMBOI Festival 2017. Photo Bryony Jackson Disclaimer This report is provided for information and it does not purport to be complete. While care has been taken to ensure the content in the report is accurate, we cannot guarantee is without flaw of any kind. There may be errors and omissions or it may not be wholly appropriate for your particular purposes. In addition, the publication is a snapshot in time based on historic information which is liable to change. -

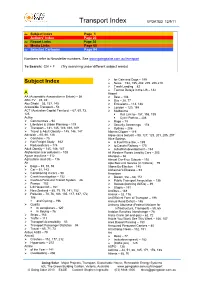

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

Minutes of Ordinary Council Meeting

Ordinary Council Meeting Minutes Tuesday 13 August 2019 Hobsons Bay City Council 13 August 2019 Ordinary Council Meeting Minutes THE COUNCIL’S MISSION We will listen, engage and work with our community to plan, deliver and advocate for Hobsons Bay to secure a happy, healthy, fair and sustainable future for all. OUR VALUES Respectful Community driven and focused Trusted and reliable Efficient and responsible Bold and innovative Accountable and transparent Recognised Council acknowledges the peoples of the Kulin nation as the Traditional Owners of these municipal lands and waterways, and pay our respects to Elders past and present. Chairperson: Cr Jonathon Marsden (Mayor) Strand Ward Councillors: Cr Angela Altair Strand Ward Cr Peter Hemphill Strand Ward Cr Tony Briffa Cherry Lake Ward Cr Sandra Wilson Cherry Lake Ward Cr Colleen Gates Wetlands Ward Cr Michael Grech (Deputy Mayor) Wetlands Ward Aaron van Egmond Chief Executive Officer Hobsons Bay City Council Hobsons Bay City Council 13 August 2019 Ordinary Council Meeting Minutes CONTENTS 1 Council Welcome ............................................................................................................ 3 2 Apologies ........................................................................................................................ 3 3 Disclosure of Interests ................................................................................................... 3 4 Minutes Confirmation .................................................................................................... -

Citylink Groundwater Management

CASE STUDY CityLink Groundwater Management Aquifer About CityLink Groundwater implications for design and construction A layer of soil or rock with relatively higher porosity CityLink is a series of toll-roads that connect major and permeability than freeways radiating outward from the centre of Design of tunnels requires lots of detailed surrounding layers. This Melbourne. It involved the upgrading of significant geological studies to understand the materials that enables usable quantities stretches of existing freeways, the construction of the tunnel will be excavated through and how those of water to be extracted from it. new roads including a bridge over the Yarra River, materials behave. The behavior of the material viaducts and two road tunnels. The latter are and the groundwater within it impacts the design of Fault zone beneath residential areas, the Yarra River, the the tunnel. A challenge for design beneath botanical gardens and sports facilities where surface suburbs and other infrastructure is getting access A area of rock that has construction would be either impossible or to sites to get that information! The initial design of been broken up due to stress, resulting in one unacceptable. the tunnel was based on assumptions of how much block of rock being groundwater would flow into the tunnel, and how displaced from the other. The westbound Domain tunnel is approximately much pressure it would apply on the tunnel walls They are often associated 1.6km long and is shallow. The east-bound Burnley (Figure 2). with higher permeability than the surrounding rock tunnel is 3.4km long part of which is deep beneath the Yarra River. -

Investigation Into Review of Parking Fines by the City of Melbourne

Investigation into review of parking fines by the City of Melbourne September 2020 Ordered to be published Victorian government printer Session 2018-20 P.P. No. 166 Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please call 9613 6222, using the National Relay Service on 133 677 if required, or email [email protected]. The Victorian Ombudsman pays respect to First Nations custodians of Country throughout Victoria. This respect is extended to their Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge their sovereignty was never ceded. Letter to the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly To The Honourable the President of the Legislative Council and The Honourable the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Pursuant to sections 25 and 25AA of the Ombudsman Act 1973 (Vic), I present to Parliament my Investigation into review of parking fines by the City of Melbourne. Deborah Glass OBE Ombudsman 16 September 2020 2 www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au Contents Foreword 5 What motivated Council’s approach? 56 Alleged revenue raising – the evidence 56 Background 6 Poor understanding of administrative The protected disclosure complaint 6 law principles 59 Jurisdiction 6 Inflexible policies and lack of discretion 60 Methodology 6 Culture and resistance to feedback 62 Scope 7 What motivated these decisions? 63 Procedural fairness 7 Council’s response 63 City of Melbourne 8 Conclusions 65 The Branch 9 The conduct of individuals 65 Relevant staff 10 Final comment 65 Conduct standards for Council officers 10 -

Public Transport Partnerships

PUBLIC TRANSPORT PARTNERSHIPS An Overview of Passenger Rail Franchising in Victoria March 2005 Department of Infrastructure PUBLIC TRANSPORT PARTNERSHIPS An Overview of Passenger Rail Franchising in Victoria March 2005 Public Transport Division Department of Infrastructure © State of Victoria 2005 Published by Public Transport Division Department of Infrastructure 80 Collins Street, Melbourne March 2005 www.doi.vic.gov.au This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 80 Collins Street, Melbourne. Minister’s Foreword In February 2004, after the failure of the original privatisation framework, the Victorian Government entered into new franchise agreements with Melbourne’s public transport companies, Yarra Trams and Connex. These partnership agreements find the balance between government support for public transport in Melbourne and the operational expertise provided by experienced private rail operators. Almost one year on, the new arrangements are running smoothly, providing stability across the public transport system and giving a solid foundation for a range of improvements in service delivery. Some of the other benefits to passengers that stem from these agreements include: • Additional front-line customer service staff; • Increased security patrols; • Improved driver training programs; • All night New Year’s Eve services; • Additional rolling stock; and • Improved standards for the upkeep of transport facilities. The key themes of this summary report include the background to the failure of the original contracts, the renegotiations, the nature of the new partnership agreements and the challenges of the refranchising process. You can obtain the latest information about Melbourne’s public transport by visiting www.doi.vic.gov.au/transport I commend this report to you. -

How to Enhance Walking and Cycling Instead of Shorter Car Trips and to Make These Modes Safer

Deliverable D6 How to enhance WALking and CYcliNG instead of shorter car trips and to make these modes safer Public WALCYNG Contract No: UR-96-SC.099 Project Coordinator: Department of Traffic Planning and Engineering, University of Lund, Sweden Partners: FACTUM Chaloupka, Praschl & Risser OHG Franco Gnavi and Carlo Bonanni City of Helsinki, City Planning Office Institute of Transport Economics Department of Psychology, University of Helsinki Instituto de Tráfico y Seguridad Vial (INTRAS), University of Valencia TransportTechnologie-Consult Karlsruhe GmbH Dutch Pedestrian Association "De Voetgangersvereniging" Chalmers University of Technology AB (Associated Contractor) Date: 15.1.1999 PROJECT FUNDED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION UNDER THE TRANSPORT RTD PROGRAMME OF THE 4th FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME Deliverable D6 WALCYNG How to enhance WALking and CYcliNG instead of shorter car trips and to make these modes safer Public Hydén, C., Nilsson, A. & Risser, R. Department of Traffic Planning and Engineering, University of Lund, Sweden & FACTUM Chaloupka, Praschl & Risser OHG, Vienna, Austria 6. Department of Psychology, University of Helsinki, Liisa Hakamies-Blomqvist, Finland 7. INTRAS, University of Valencia, Enrique J. Carbonell Vayá, Beatriz Martín, Spain 8. Transport Technologie-Consult Karlsruhe GmbH (former Verkehrs-Consult Karlsruhe), Rainer Schneider, Germany 9. De Voetgangersvereniging, Willem Vermeulen, The Netherlands 10. Road and Traffic Planning Department, Chalmers University of Technology AB, Olof Gunnarsson, Sweden TABLE OF CONTENTS -

TAG A4 Document

Transport Priorities Contents Page What is the Eastern Transport Coalition? 3 Investing in the East is investing in Victoria 4 P r iorities 5 Projects Train and Tram 7 - 14 Bus 15 - 19 Roads 20 - 24 Walking and Cycling 25 - 31 What’s next? 32 Version 1 What is the Eastern Transport Coalition? The Eastern Transport Coalition (ETC) consists of Melbourne’s seven eastern metropolitan councils: City of Greater Dandenong, Knox City Council, Manningham City Council, Maroondah City Council, City of Monash, City of Whitehorse and Yarra Ranges Shire Council. The ETC advocates for sustainable and integrated transport services to reduce the level of car dependency so as to secure the economic, social and environmental wellbeing of Melbourne’s east. We aim to work in The Eastern Transport Coalition has put partnership with federal and state together a suite of projects and governments to ensure the future priorities to promote connectivity, sustainability of Melbourne’s eastern region. In liveability, sustainability, productivity order to preserve the region’s economic and eciency throughout Melbourne’s promise and ensure the wellbeing of our residents, it is crucial that we work to promote eastern region. The ETC is now better transport options in the east. advocating for the adoption and implementation of each of the transport priorities proposed in this document by Vision for the East the Federal and State Government. The ETC aims for Melbourne’s east to become Australia’s most liveable urban region connected by world class transport linkages, ensuring the sustainability and economic growth of Melbourne. With better transport solutions, Melbourne’s east will stay the region where people build the best future for themselves, their families, and their businesses. -

Integrated Transport Planning

Integrated Transport Planning Transport Integrated | August 2021 August Integrated Transport Planning August 2021 Independent assurance report to Parliament 2021–22: 01 Level 31, 35 Collins Street, Melbourne Vic 3000, AUSTRALIA 2021–22: T 03 8601 7000 E [email protected] 01 www.audit.vic.gov.au This report is printed on Monza Recycled paper. Monza Recycled is certified Carbon Neutral by The Carbon Reduction Institute (CRI) in accordance with the global Greenhouse Gas Protocol and ISO 14040 framework. The Lifecycle Analysis for Monza Recycled is cradle to grave including Scopes 1, 2 and 3. It has FSC Mix Certification combined with 99% recycled content. ISBN 9781921060151 Integrated Transport Planning Independent assurance report to Parliament Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2021 PP no 248, Session 2018–21 The Hon Nazih Elasmar MLC The Hon Colin Brooks MP President Speaker Legislative Council Legislative Assembly Parliament House Parliament House Melbourne Melbourne Dear Presiding Officers Under the provisions of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Integrated Transport Planning. Yours faithfully Dave Barry Acting Auditor-General 4 August 2021 The Victorian Auditor-General’s Office acknowledges Australian Aboriginal peoples as the traditional custodians of the land throughout Victoria. We pay our respect to all Aboriginal communities, their continuing culture and to Elders past, present and emerging. Integrated Transport Planning | Victorian Auditor-General´s Report Contents Audit snapshot ....................................................................................................................................... -

Towards More Sustainable Cities: Building a Public Transport Culture

Towards More Sustainable Cities: Building a Public Transport Culture Submission by the Bus Industry Confederation to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment and Heritage’s Inquiry into Sustainable Cities 2025. Canberra, October, 2003. Table of Contents Executive Summary Key Findings Some Particular Conclusions 1. Scope ...................................................................................................................... 2. The Sustainability of Australia’s City Transport Systems ........................................ 2.1 Sustainability Criteria........................................................................................... 2.2 Externalities ......................................................................................................... 2.3 Economic Sustainability....................................................................................... 2.3.1 Congestion Costs ........................................................................................... 2.3.2 Dynamic Urban Economies............................................................................ 2.4 Improving Access................................................................................................. 2.4.1 Melbourne ..................................................................................................... 2.4.2 Sydney........................................................................................................... 2.4.3 Hobart...........................................................................................................