Public Transport Partnerships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WODONGA Train Crash 6.02

RAIL INVESTIGATION REPORT Derailment of passenger train 8622, Sydney – Melbourne daylight XPT service Wodonga, Victoria 25 April 2001 ATSB Derailment of passenger train 8622, Sydney – Melbourne daylight XPT service ISBN 0 642 20047 5 odonga 6.02 W 1800 621 372 621 1800 www.atsb.gov.au Department of Transport and Regional Services Australian Transport Safety Bureau RAIL INVESTIGATION REPORT Derailment of passenger train 8622, Sydney – Melbourne daylight XPT service, Wodonga, Victoria 25 April 2001 ISBN 0 642 20047 5 June 2002 This report was produced by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB), PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608. Readers are advised that the ATSB investigates for the sole purpose of enhancing safety. Consequently, reports are confined to matters of safety significance and may be misleading if used for any other purpose. As ATSB believes that safety information is of greatest value if it is passed on for the use of others, copyright restrictions do not apply to material printed in this report. Readers are encouraged to copy or reprint for further distribution, but should acknowledge ATSB as the source. ii CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2. INTRODUCTION 5 3. INVESTIGATION METHODOLOGY 7 4. FACTUAL INFORMATION 9 4.1.1 XPT background 9 4.1.2 Wodonga 10 4.2 Sequence of events 11 4.2.1 The incident 11 4.2.2 Subsequent events 13 4.3 Injuries 15 4.4 Damage 15 4.4.1 Damage to the train 15 4.4.2 Damage to the rail infrastructure 18 4.5 Train crew involved 20 4.6 Train Information 21 4.6.1 Train Consist 21 4.6.2 Rolling stock date -

TTF Smartcard Ticketing on Public Transport 2010

Tourism & Transport Forum (TTF) Position Paper Smartcard ticketing on public transport July 2010 Tourism & Transport Forum (TTF) is a national, Member‐funded CEO forum, advocating the public policy interests of the 200 most prestigious corporations and institutions in the Australian tourism, transport, aviation & investment sectors. CONTENTS OVERVIEW 2 SMARTCARD TECHNOLOGY 3 ADVANTAGES OF SMARTCARD TICKETING 3 CHALLENGES FOR IMPLEMENTATION 6 SMARTCARD TICKETING IN AUSTRALIA 8 SMARTCARD TICKETING INTERNATIONALLY 10 INNOVATION IN SMARTCARD TECHNOLOGY 12 LOOKING AHEAD 14 CONCLUDING REMARKS 14 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT: CAROLINE WILKIE NATIONAL MANAGER, AVIATION & TRANSPORT TOURISM & TRANSPORT FORUM (TTF) P | 02 9240 2000 E | [email protected] www.ttf.org.au In short: 1. Smartcard ticketing provides convenience for commuters and efficiency gains for transport service providers. 2. Smartcard systems have been introduced in Australian cities with varying degrees of success. 3. International experience suggests that successful implementation may take many years, and difficulties are commonplace. 4. Overall, the benefits of smartcard ticketing overwhelmingly outweigh the costs and challenges that may arise in implementation. Overview Smartcard technology is being implemented around the world as a substitute for cash transactions in various capacities. When applied to public transport fare collection, smartcards eliminate the need for commuters to queue for tickets and reduce the burden on transport providers to process fare transactions. In recent years, benefits such as decreased travel times and general convenience to commuters have driven a shift towards smartcard ticketing systems on public transport systems in Australia and around the world. As well as providing more efficient transport services to commuters, smartcard ticketing systems enable service providers and transit authorities to collect comprehensive data on the travel behaviour of commuters. -

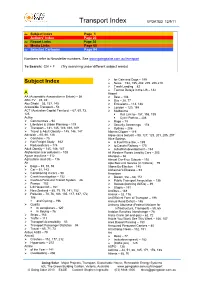

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

AATTC DL Lists 12 E7.Xlsx

DISTRIBUTION LIST April 2012 The AATTC Distribution Service aims to supply as many current Australian timetables and information brochures as possible. It also provides historical material from Australia and overseas as it becomes available. Some of the main items of interest in this month’s Distribution List include: • ARTC Master Train Plan (Working Timetable) from 1 April 2012 (Item 1). • Some old interstate train timetables (Items 2, 3, 4) • More CityRail and CountryLink train rosters (Item 5-9). • Another set of RailCorp Freight Working Timetables, this time from 31 March 2012 (Item 12). • Possibly the last Travel Guide to be issued for the Sydney Light Rail and Monorail (Item 13). • Timetables from Upper Darling Range Branch railway in Western Australia (Item 22) and a history of the line (Item 100). These came from a presentation by David Hennell to the Melbourne Division meeting in March 2012. • A selection of bus timetables in northern NSW (Items 33 – 39). • The heaviest timetable in this List: Ballarat Transit – it weighs 234 grams (Item 47). • Complete set of the Transperth bus timetables issued on 19 February 2012 (Item 54). • Sets of the Mornington Peninsula Dial a Bus door to door bus services from many localities (Item 87). April 2012 items were supplied by: Steve Bigwood, Barry Blair, Adrian Dessanti, Scott Ferris, Hilaire Fraser, Frank Goldthorpe, Stephen Gray, Robert Henderson, David Hennell, Peter Hobbis, Les Hyland, Victor Isaacs, Tony McIlwain, Len Regan, Lourie Smit, Peter Walhouse, Roger Wheaton, David Whiteford, Sydney Grab Box. Payments for orders or for creating advance credit can be made by: • Postage stamps (any denominations). -

NORTH WEST Freight Transport Strategy

NORTH WEST Freight Transport Strategy Department of Infrastructure NORTH WEST FREIGHT TRANSPORT STRATEGY Final Report May 2002 This report has been prepared by the Department of Infrastructure, VicRoads, Mildura Rural City Council, Swan Hill Rural City Council and the North West Municipalities Association to guide planning and development of the freight transport network in the north-west of Victoria. The State Government acknowledges the participation and support of the Councils of the north-west in preparing the strategy and the many stakeholders and individuals who contributed comments and ideas. Department of Infrastructure Strategic Planning Division Level 23, 80 Collins St Melbourne VIC 3000 www.doi.vic.gov.au Final Report North West Freight Transport Strategy Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... i 1. Strategy Outline. ...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Strategy Outcomes.................................................................................................................1 1.3 Planning Horizon.....................................................................................................................1 1.4 Other Investigations ................................................................................................................1 -

Yarra Trams Temporary Exemptions Report 2018 FINAL

Temporary Exemptions Report Melbourne Tram Service Reporting period: 1 October 2017 to 30 September 2018 Contents Context 3 Introduction 4 Part A – Exemptions from the Transport Standards 6 2.1 (i) Access paths – Unhindered passage 6 2.1 (ii) Access paths – Unhindered passage 8 2.4 Access paths – Minimum unobstructed width 9 2.6 Access paths - Conveyances 20 4.2 Passing areas – Two-way access paths and aerobridges 21 5.1 Resting points – When resting points must be provided 27 6.4 Slope of external boarding ramps 28 11.2 Handrails and grabrails – Handrails to be provided on access paths 29 17.5 Signs – Electronic notices 30 Part B – Exemptions from the Premises Standards 31 H2.2 Accessways 31 H2.2 Accessways 32 H2.2 Accessways 33 H2.2 Accessways 34 H2.4 Handrails and grabrails 35 2 Context The Public Transport Development Authority trading as Public Transport Victoria (PTV), established under the Transport Integration Act 2010 (Vic), is the statutory authority responsible for managing the tram network on behalf of the State of Victoria. Pursuant to the Franchise Agreement – Tram between PTV and KDR Victoria Pty Ltd (trading as Yarra Trams) dated 2 October 2017, Yarra Trams is the franchise operator of the Melbourne metropolitan tram network. Yarra Trams is also a member of the Australasian Railway Association (ARA). On 1 October 2015, the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) granted temporary exemptions to members of the ARA in relation to section 55 of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth), various provisions of the Disability Standards for Accessible Public Transport 2002 (Transport Standards) and the Disability (Access to Premises – Buildings) Standards 2010 (Premises Standards). -

Locolines Edition 68

LOCOLINES Contents EDITION 68 APR 2017 Loco Lines is published by the Locomotive Secretary’s Report 3 Division of the Australian Rail, Tram & Bus Industry Union – Victorian Branch. Presidents Report 8 Loco Lines is distributed free to all financial Assistant Sec Report 10 members of the Locomotive Division. Retired Enginemen also receive the V/Line S.C.S Report 13 magazine for free. It is made available to non-members at a cost of $20.00 per year. V/Line Stranded Gauge 15 Advertisements offering a specific benefit to Locomotive Division members are Where is it? 1 6 published free of charge. Heritage groups are generally not charged for advertising or ‘A special train in half an hour’ Article 1 8 tour information. Maurice Blackburn 21 Views or opinions expressed in published contributions to Loco Lines are not necessarily those of the Union Office. V/Line Cab Committee Report 28 We also reserve the right to alter or delete text for legal or other purposes. ‘Livestock Traffic’ Article 30 Contributions are printed at the discretion Talkback with Hinch 3 2 of the publisher. Signal Sighting V/line 35 Loco Lines, or any part thereof, cannot be reproduced or distributed without the Nelsons Column 3 6 written consent of the Victorian Locomotive Division. ‘Australia’s forgotten Volunteers’ 38 Publisher Marc Marotta Retirements/ Resignations 40 Have your Say 4 1 Membership form 44 Locomotive Division Representatives Divisional Executive Divisional Councillors Secretary: ...........Marc Marotta 0414 897 314 Metropolitan : ……….......Paris Jolly 0422 790 624 Assist. Sec: ...Jim Chrysostomou 0404 814 141 Metropolitan :…….... President: .............Wayne Hicks 0407 035 282 Metropolitan : ….... -

October 2006

N e w s www.ptua.org.au ISSN 0817 – 0347 Volume 30 No. 4 October 2006 State election looms: Parties challenged on transport Going into the state election, the PTUA is (including duplication of single track and challenging the major political parties to commit to signalling upgrades where this is necessary) funding real solutions to Melbourne and Victoria’s • transport problems. Upgrades to regional town bus services in line with those taking place in Melbourne: routes to With endemic traffic congestion and pollution, and operate 7 days a week into the evening (despite a brief respite recently) petrol prices set to • continue to climb, it is time to offer more people a Genuine priority for bus and tram services to genuine alternative to driving. ensure these vehicles are not delayed by heavy traffic Key commitments must include: • Commence removal of level crossings, • Reform of the Planning and Transport beginning with those worst affected by high Ministries to overhaul the management culture train frequencies, tram/train crossings and buses and ensure a holistic view of land-use planning held up in traffic and transport issues, to ensure the best “triple- bottom-line” (environmental, social, economic) The PTUA was highly critical of the government’s outcomes Meeting Our Transport Challenges document when it was released in May, because for all the money • Redesign of the bus system into a co-ordinated, being spent, very little is going towards getting direct, frequent, easy-to-understand network people out of their cars and onto public transport. that genuinely complements the train and tram With a few trivial exceptions, there is no systems in providing all of Melbourne with commitment to any the urgent priorities listed transport choices above. -

VR Annual Report 1963

1963 VICTORIA VICTORIAN RAILWAYS REPORT OF THE VICTORIAN RAILWAYS COMMISSIONERS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30th JUNE, 1963 PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO ACT 7 ELIZABETH 11. No. 6355 By Authority: A. C. BROOKS. GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 19.-[68. 3n.].-12005/63. CONTENTS PAGE CoMMISSIONERs' REPORT l HEADS OF BRANCHES 2:3 APPENDICEs- APPENDIX Balance-sheet l 24 Financial Results (Totals), Summary of 2 26 Financial Results (Details), Summary of 2A 27 Reconciliation of Railway and Treasury Figures (Revenue and Working Expenses), 3 2H Working Expenses, Abstract of 4 2n Working Expenses and Earnings, Comparative Analysis of 5 :30 Total Cost of Each Line and of Rolling Stock, &c. 6 :p- General Comparative Statement for Last Fifteen Years 7 :3H Statistics : Passengers, Goods Traffic, &c. 8 41 Mileage : Train, Locomotive, and Vehicle 9 42 Salaries and Wages, Total Amount Paid 10 44 Staff Employed in Years Ended 30th June, 1963 and 1962 ll 45 Locomotives, Coaching Stock, Goods and Service Stock on Books 12 46 Railway Accident and Fire Insurance Fund ... 13 49 New Lines Opened for Traffic or Under Construction, &c. 14 iiO Mileage of Railways and Tracks 15 ;)] Railways Stores Suspense Account 16 iiz Railway Renewals and Replacements Fund 17 52 Depreciation-Provision and Accrual 18 52 Capital Expenditure in Years Ended 30th June, 1963 and 1962 19 ii3 Passenger Traffic and Revenue, Analysis of ... 20 ii4 Goods and Live Stock Traffic and Revenue, Analysis ot 21 55 Traffic at Each Station 22 ii6 His Excellency Sir Rohan Delacombe, Governor of Vi ctoria, and Lady Delacombe about to entrain at Spencer Street for a visit to western Victoria. -

APPENDIX a – Rail Manufacturing in Victoria

Rail Manufacturing in Victoria Summary of key points • Approximately 1000 people are employed directly by the major rail rolling stock manufacturers in Victoria and another 5,000 to 10,000 employed in their supply chain. • Rail rolling stock manufacturing is directly influenced by State Government procurement policy and purchasing decisions. Victorian Government local content rules are weak compared to interstate and international examples. In recent years, the New South Wales and Victorian Governments have collectively awarded $3.8 billion worth of contracts to overseas manufacturers. • The Victorian Transport Plan commits to $3.6 billion in new investment in rail rolling stock over 4 years. Manufacturing 50 % of these new vehicles in Victoria would create 2,250 full- time jobs directly and another 5,400 – 6,300 full-time jobs indirectly in the supply chain. • A strong rail manufacturing sector could provide thousands of jobs for retrenched automotive workers as long as the training system was made more flexible and relevant to industry needs. • Ongoing investment in local manufacturing would ensure the continued existence of a skilled workforce and provide a solid platform for expanded export opportunities. Once local manufacturing capacity is allowed to erode it is difficult, if not impossible to regain. Introduction Victoria is facing the twin challenges of climate change and the global financial crisis. Already the economic downturn has cost thousands of Victorian jobs, many in the manufacturing sector and expectations are for unemployment to rise further in the coming year. At the same time, the impacts of climate change and peak oil will be felt most by low income and disadvantaged Victorians, particularly those living on the outskirts of our cities. -

TRAM ROUTE 86 CORRIDOR IMPROVEMENT PROJECT COMMUNITY REFERENCE GROUP – WESTGARTH Recommendation Report

TRAM ROUTE 86 CORRIDOR IMPROVEMENT PROJECT COMMUNITY REFERENCE GROUP – WESTGARTH Recommendation Report Background The Westgarth Community Reference Group for the Tram Route 86 Corridor Improvement Project was convened by Council to provide community input into the re-work of the Project. Seven nominees were selected by Council for the group and six members participated throughout the four meetings which were scheduled fortnightly over July/August 2009. This Report contains a summary of the discussions and debates that were held between group members over the four meetings. The Notes of each meeting are presented in Appendix 1. The Report is divided into sections; 1. The Recommendations 2. Other Considerations 3. Appendices The group wishes to record again its strong opposition to any proposals that result in the creation of any form of sliplane which has the effect of bringing High Street traffic in closer proximity to those houses located on High Street south of Westgarth Street. Council should be aware that in the course of this process an option was presented to the Reference Group and was seen as a breach of Council’s prior undertakings that a sliplane would not form part of any future considerations. The Recommendations In the first two meetings the group discussed the issues that were raised with the initial proposal for the Westgarth section. These included: Impact on businesses Improved public transport & Pedestrian Access vs Vehicle Access Disability Access and Safety (40km/h) Resident Amenity vs Public transport access Ruckers -

Investigation of the Relationship Between Transit Network Structure and the Network Effect – the Toronto & Melbourne Experience

INVESTIGATION OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRANSIT NETWORK STRUCTURE AND THE NETWORK EFFECT – THE TORONTO & MELBOURNE EXPERIENCE By Karen Frances Woo A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Applied Science Department of Civil Engineering University of Toronto © Copyright by Karen Frances Woo 2009 Investigation of the Relationship between Transit Network Structure and the Network Effect – The Toronto & Melbourne Experience Karen Frances Woo Master of Applied Science Department of Civil Engineering University of Toronto 2009 Abstract The main objective of this study was to quantitatively explore the connection between network structure and network effect and its impact on transit usage as seen through the real-world experience of the Toronto and Melbourne transit systems. In this study, the comparison of ridership/capita and mode split data showed that Toronto’s TTC has better performance for the annual data of 1999/2001 and 2006. After systematically investigating travel behaviour, mode choice factors and the various evidence of the network effect, it was found that certain socio-economic, demographic, trip and other design factors in combination with the network effect influence the better transit patronage in Toronto over Melbourne. Overall, this comparative study identified differences that are possible explanatory variables for Toronto’s better transit usage as well as areas where these two cities and their transit systems could learn from one another for both short and long term transit planning and design. ii Acknowledgments This thesis and research would not have been possible without the help and assistance of many people for which much thanks is due.