Essays in Behavioral Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print Journalism's Framing of Female Candidates in The

Joining the World of Journals Welcome to the nation’s first and, to our knowledge, only undergraduate research journal in communi- cations. We discovered this fact while perusing the Web site of the Council on Undergraduate Research, which lists and links to the 60 or so undergraduate research journals nationwide (http://www.cur.org/ugjournal. html). Some of these journals focus on a discipline (e.g., Journal of Undergraduate Research in Physics), some are university-based and multidisciplinary (e.g., MIT Undergraduate Research Journal), and some are university-based and disciplinary (e.g., Furman University Electronic Journal in Undergraduate Mathematics). The Elon Journal is the first to focus on undergraduate research in journalism, media and communi- cations. The School of Communications at Elon University is the creator and publisher of the online journal. The second issue was published in Fall 2010 under the editorship of Dr. Byung Lee, associate professor in the School of Communications. The three purposes of the journal are: • To publish the best undergraduate research in Elon’s School of Communications each term, • To serve as a repository for quality work to benefit future students seeking models for how to do undergraduate research well, and • To advance the university’s priority to emphasize undergraduate student research. The Elon Journal is published twice a year, with spring and fall issues. Articles and other materials in the journal may be freely downloaded, reproduced and redistributed without permission as long as the author and source are properly cited. Student authors retain copyright own- ership of their works. Celebrating Student Research This journal reflects what we enjoy seeing in our students -- intellectual maturing. -

A Prima Vista

A PRIMA VISTA a survey of reprints and of recent publications 2011/1 BROEKMANS & VAN POPPEL Van Baerlestraat 92-94 Postbus 75228 1070 AE AMSTERDAM sheet music: + 31 (0)20 679 65 75 CDs: + 31 (0)20 675 16 53 / fax: + 31 (0)20 664 67 59 also on INTERNET: www.broekmans.com e-mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS A PRIMA VISTA 2011/1 PAGE HEADING 03 PIANO 2-HANDS 14 PIANO 4-HANDS 15 2 AND MORE PIANOS, HARPSICHORD 16 ORGAN 20 KEYBOARD 21 ACCORDION 22 BANDONEON 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITHOUT AC COMPANIMENT: 22 VIOLIN SOLO 24 VIOLA SOLO, CELLO SOLO, DOUBLE BASS SOLO, VIOLA DA GAMBA SOLO 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 24 VIOLIN with accompaniment 26 VIOLIN PLAY ALONG 27 VIOLA with accompaniment, VIOLA PLAY ALONG 28 CELLO with accompaniment 29 CELLO PLAY ALONG, VIOLA DA GAMBA with accompaniment 29 2 AND MORE STRING INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 33 FLUTE SOLO, OBOE SOLO, COR ANGLAIS SOLO, CLARINET SOLO, SAXOPHOHNE SOLO, BASSOON SOLO 34 TRUMPET SOLO, HORN SOLO, TROMBONE SOLO, TUBA SOLO 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 34 FLUTE with accompaniment 36 FLUTE PLAY ALONG, OBOE with accompaniment 37 OBOE PLAY ALONG, CLARINET with accompaniment 38 CLARINET PLAY ALONG, SAXOPHONE with accompaniment 39 SAXOPHONE PLAY ALONG 40 BASSOON with accompaniment, BASSOON PLAY ALONG 41 TRUMPET with accompaniment 42 TRUMPET PLAY ALONG, HORN with accompaniment 43 HORN PLAY ALONG, TROMBONE with accompaniment, TROMBONE PLAY ALONG 44 TUBA with accompaniment -

Pressemitteilung 2007-06-06 Über 100 Veranstaltungen Im

Pressemitteilung 2007-06-06 Ausstellungszentrum Hessenhallen Über 100 Veranstaltungen im Geschäftsjahr 2006 – Highlights: Revolverheld und Deutsche Superstars Die M.A.T. Objekt GmbH, Vermieter und Betreiber der Hessenhallen hat die Hundert geknackt: Genau 124 Veranstaltungen an insgesamt 146 Veranstaltungstagen waren zu Gast in Gießens Ausstellungszentrum. Mehr als 160 000 Besucher strömten im Laufe des Jahres zu den Konzerten der „Deutschland sucht den Superstar“-Finalisten Tobias Regner und Mike Leon Grosch, zu Revolverheld und Subway to Sally, fanden neue Schätze auf dem Antik & Trödelmarkt, informierten sich auf Fach- und Verbrauchermessen – oder drehten eine Runde auf dem Eis. Der Vergleich zum Vorjahr belegt: Besucherzuwachs sowie über vierzig Prozent mehr Veranstaltungen geben Anlass, ein positives Fazit zu ziehen, wie dies auch Thomas Luh, Geschäftsführer der M.A.T. Objekt GmbH bestätigt. „Dank der Unterzeichnung des Erbpachtvertrages mit der Stadt Gießen hatten wir allen Grund, optimistisch ins Jahr 2007 zu starten. Schon in der ersten Jahreshälfte konnten wir hochwertige Veranstaltungen verzeichnen, wie zum Beispiel das Konzert von Christina Stürmer, die Lesung mit Christoph Maria Herbst oder die Fachmesse World of Bike.“ Vielseitigkeit und Qualität sowohl der gastierenden Veranstaltungen als auch der Leistungen des Gastgebers haben sich in den Hessenhallen zur erfolgreichen Tradition entwickelt. So war 2006 die Internationale Rassehundeausstellung (CACIB) in Gießen zu Gast und bereicherte das Programm um die regelmäßig stattfindenden -

Music Markets and the Adoption of Novelty : Experimental Approaches Anna Bernard

Music markets and the adoption of novelty : experimental approaches Anna Bernard To cite this version: Anna Bernard. Music markets and the adoption of novelty : experimental approaches. Economics and Finance. Université Panthéon-Sorbonne - Paris I, 2017. English. NNT : 2017PA01E020. tel- 01792982 HAL Id: tel-01792982 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01792982 Submitted on 16 May 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris 1 - Panthéon Sorbonne U.F.R de Sciences Economiques Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne Thèse Pour l’obtention du titre de Docteur en Sciences Economiques présentée et soutenue publiquement le 6 juin 2017 par Anna Bernard Music Markets and the Adoption of Novelty: Experimental Approaches Directeur de thèse Louis Lévy-Garboua Professeur à l’Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne Jury Rapporteurs : Charles Noussair Professeur à The University of Arizona Paul Belleflamme Professeur à l’Université Aix Marseille Président : François Gardes Professeur à l’Université de Paris I Examinateurs : Matteo M. Galizzi Professeur Assistant à la London School of Economics Françoise Benhamou Professeure à l’Université Paris 13 L’Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne n’entend donner aucune approbation, ni improbation aux opinions émises dans cette thèse; elles doivent être considérées comme propres à leur auteur. -

Liebes Aus Bei Sarah Connor

Ausgabe : Dezember 2008 2 Mini Poster: LaFee& Jenn ifer Kae Bambi 2008 Nevio Autogrammstunde in Berlin Liebes Aus bei Sarah Connor Themen * News * US5 – mit neuem Album zurück * Liebes Aus bei Kate und Ben * The Prodigy – Comeback mit neuem Album * Sarah und Marc (NOT) in Love * EMA’s kommen nach Berlin * Bushido schliesst mit MTV ab * Ich und Ich auf Herbsttour * Bushido - Gratis Konzert in der Berliner O2 World * Katy Perry kommt nach Deutschland * Kuschelrock * Pussycat Dolls kommen auf Tour * Britney kommt nach Europa * Leserbericht: * 2nd Chance – Da Weihnachtsalbum - Highschool Musical 3 Premiere in München * Bambi 2008 * Terminkalender * EMA – die Gewinner * Tourguide * LaFee Autogrammstunde * Alben Veröffentlichungen * 2 Mini Poster: Jennifer Kae & LaFee * Single Veröffentlichungen * Kate Hall – neue Single * Sampler des Monats * DJ Ötzi auf Erfolgskurs * TV Special * New Kids on the Block – neue Single * DVD Veröffentlichung * Take That Just Celebrities MAG - Impressum - Redaktion: Just Celebrities MAG Postanschrift: Just Celebrities MAG Postfach 30 93 43 10761 Berlin E-Mail: [email protected] Inhaber: Jacqueline Quintern Steuernummer: 35/481/60001 Redaktionsleitung: Jacqueline Quintern ([email protected]) Nicole Kubelka ([email protected]) Bildjournalist Jacqueline Quintern, Nicole Kubelka Redakteur: Nicole Kubelka Layout: Jacqueline Quintern Homepage: www.just-celebrities.de (das begleitende Online Magazin) My Space: www.myspace.com/justcelebrities Redaktion: [email protected] Redaktionsleitung: Jacqueline Quintern ([email protected]) Nicole Kubelka ([email protected]) Bildjournalist: Jacqueline Quintern, Nicole Kubelka Redakteur: Nicole Kubelka Webdesign: Jacqueline Quintern Just Celebrities MAG // NEWS Rückblick Nevio Passaro stellt sein neues Album vor Wie schon in der letzten Ausgabe erwähnt, hat Nevio Passaro bei Universal Music, sein zweites Album veröffentlicht. -

Language NAME SONGNAME Danish Søs Fenger Den Jeg

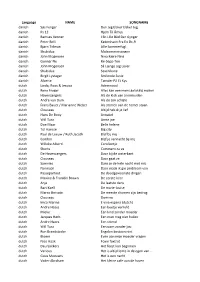

Language NAME SONGNAME danish Søs Fenger Den Jeg Elsker Elsker Jeg danish Ps 12 Hjem Til Århus danish Bamses Venner I En Lille Båd Der Gynger danish Peter Belli København Fra En Dc-9 danish Bjørn Tidman Lille Sommerfugl danish Shubidua Midsommersangen danish John Mogensen Nina Kære Nina danish Gunnar Nu Re-Sepp-Ten danish John Mogensen Så Længe Jeg Lever danish Shubidua Sexchikane danish Birgit Lystager Smilende Susie danish Alberte Tænder På Et Kys dutch Linda, Roos & Jessica Ademnood dutch Rene Froger Alles kan een mens gelukkig maken dutch Havenzangers Als de klok van arnemuiden dutch Andre van Duin Als de zon schijnt dutch Frans Bauer / Marianne Weber Als sterren aan de hemel staan dutch Clouseau Altijd heb ik je lief dutch Hans De Booy Annabel dutch Will Tura Arme joe dutch Doe Maar Belle helene dutch Tol Hansse Big city dutch Paul de Leeuw / Ruth Jacoth Blijf bij mij dutch Gordon Blijf je vannacht bij mij dutch Willeke Alberti Carolientje dutch Shorts Comment ca va dutch De Havenzangers Daar bij de waterkant dutch Clouseau Daar gaat ze dutch Sjonnies Dans je de hele nacht met mij dutch Normaal Daor maak ik gin probleem van dutch Passepartout De doodgewoonste dingen dutch Maxine & Franklin Brown De eerste keer dutch Anja De laatste dans dutch Bart Kaell De marie-louise dutch Marco Borsato De meeste dromen zijn bedrog dutch Clouseau Domino dutch Imca Marina E viva espana (dutch) dutch Andre Hazes Een beetje verliefd dutch Mieke Een kind zonder moeder dutch Jacques Herb Een man mag niet huilen dutch Andre Hazes Een vriend dutch Will Tura Eenzaam zonder jou dutch Ron Brandsteder Engelen bestaan niet dutch Bloem Even aan mijn moeder vragen dutch Nico Haak Foxie foxtrot dutch Deurzakkers Het feest kan beginnen dutch Various Het is altijd lente in de ogen van .. -

Gesamtwertung BAYERN 3-Charts Zur 2000. Sendung

GESAMTWERTUNG BAYERN 3-CHARTS ZUR 2000. SENDUNG Woch Einstieg Platz Titel Interpret Punkte 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 en s-Datum Ein Stern (der deinen Namen 1 DJ Ötzi & Nik P 669 57 16.02.07 13 13 6 9 7 5 2 1 1 trägt) 2 Perfect Ed Sheeran 402 26 29.09.17 15 6 1 3 1 3 Wind Of Change Scorpions 392 30 12.04.91 12 5 5 3 2 2 1 4 Despacito Luis Fonsi feat. Daddy Yankee 386 28 24.03.17 15 2 3 2 3 1 1 1 5 In My Mind Dynoro & Gigi D'Agostino 374 30 15.06.18 15 2 3 1 3 2 3 1 6 Poker Face Lady Gaga 348 25 06.03.09 12 5 3 1 1 1 2 Sarah Brightman & Andrea 7 Time To Say Goodbye 341 24 06.12.96 11 4 4 2 2 1 Bocelli 8 The Sound Of Silence Disturbed 337 26 15.07.16 6 9 4 1 4 1 1 9 Human Rag'n'Bone Man 330 24 26.08.16 10 7 2 1 1 1 2 10 Shallow Lady Gaga & Bradley Cooper 314 30 05.10.18 3 6 6 6 4 2 1 1 1 11 Sweat Inner Circle 307 20 28.08.92 14 1 2 2 1 12 Conquest Of Paradise Vangelis 304 24 02.12.94 9 3 4 3 1 2 2 13 Dragostea din tei O-Zone 303 21 21.05.04 13 1 1 3 1 1 1 14 What's Up 4 Non Blondes 297 20 30.07.93 13 1 2 1 1 1 1 15 Mambo No. -

Sanatci Adin Gore

SANATÇI ADINA GÖRE SIRALI / SORTED BY ARTIST NAME!(K)ARAOKE @ THE WALL 101 Dalmatians!Cruella De Vil 10CC!Dreadlock Holiday 2 fabiola feat. Medusa!New Year's Day 3 Doors Down!Be Like That 3 Doors Down!Here Without You 3 Doors Down!It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down!Kryptonite 3 Doors Down!Loser 3 Doors Down!When I'm Gone 3 Inches Of Blood!Deadly Sinners 30 Seconds To Mars!Attack 30 Seconds To Mars!From Yesterday 30 Seconds to Mars!The kill 3OH!3!Double Vision 4 Non Blondes!What's Up? 50 Cent!In da club 50 Cent feat Justin Timberlake!Ayo Technology A Flock of Seagulls!I Ran (So Far Away) A Perfect Circle!Judith A-ha!Foot Of The Mountain a-ha!Hunting High And Low A-ha!Take On Me A-Ha!The Sun Always Shines on TV A-Teens!Mamma Mia A-Teens!Super Trooper Aaliyah!Try again ABBA!Chiquitita ABBA!Dancing Queen ABBA!Does Your Mother Know? ABBA!Fernando ABBA!Gimme Gimme Gimme ABBA!Honey Honey ABBA!I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA!I Have A Dream ABBA!Knowing Me, Knowing You ABBA!Mamma Mia ABBA!Money Money Money ABBA!One Of Us 1 SANATÇI ADINA GÖRE SIRALI / SORTED BY ARTIST NAME!(K)ARAOKE @ THE WALL ABBA!Ring Ring ABBA!SOS ABBA!Summer Night City ABBA!Super Trouper ABBA!Take A Chance On Me ABBA!Thank You For The Music ABBA!That's Me ABBA!The Name Of The Game ABBA!The Winner Takes It All ABBA!Voulez Vous ABBA!Waterloo AC/DC !Back in Black (Live) AC/DC !Dirty deeds done dirt cheap (Live) AC/DC !Fire your Guns (Live) AC/DC !For those about to Rock (We salute you) AC/DC !Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC !Hell ain't a bad place to be (Live) AC/DC !Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC !High Voltage (Live) AC/DC !Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC !Jailbreak (Live) AC/DC !Let there be Rock (Live) AC/DC !Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC !Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC !T.N.T. -

Services Magazines Television Books Digital Shows Radio & Music International

experience! Radio & Music Shows Television Magazines Books Digital Services Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 270 International D-33311 Gütersloh www.bertelsmann.de ENGL_ERLEBEN_00_Umschlag.indd 2 28.03.13 12:16 ENGL_ERLEBEN_03_Schmutztitel.indd 3 28.03.13 12:17 04 Contents 05 experience! Television Shows Books International Magazines Digital Radio & Music Services Good news, bad news. And Exciting shows, popular docu- From draft manuscript to Opening up growth markets: China, Spain, India, France: Success with new media: Clicking into the future: How a Tailor-made solutions the hard work that goes into mentaries and happy winners bestseller: The long road to Corporate Centers in China, G + J magazines also have a The young qeep team French radio station wins new for services and customers presenting it reputably and in over 20 countries producing a successful book Brazil and India strong international presence develops fresh ideas for listeners daily worldwide successfully Without American Idol pop star Kelly Random House is the world’s biggest On the fringes of Bertelsmann’s global It’s common knowledge that, with titles mobile phones Few media face such great challenges More than 63,000 employees in Every evening Peter Kloeppel, Ulrike Clarkson would probably still be the trade book publisher, based in New York. management meeting we interviewed like stern, Geo and Brigitte, Gruner+Jahr When Bertelsmann invests several as radio at this point. The days of long 40 countries are hard at work serving von der Groeben and their colleagues girl next door from Texas. And without The books of many international best- Annabelle Yu Long, Thomas Macken- is the home of fascinating magazines in millions of euros in a Cologne start-up, radio programs are gone, as are those business customers in many different face the cameras. -

Aufgelöst Und Abgetaucht

Medien TV-SHOWS Aufgelöst und abgetaucht Der Rummel um den Abgang eines Kandidaten bei „Deutschland sucht den Superstar“ bestätigt alte Vorurteile: Casting-Shows sind keine TV-Talentsuche, sondern musikalisch verpackte Soap-Operas. Doch ein Blick auf ähnliche Sendungen in den USA zeigt: Es geht auch anders. Quotenknick Durchschnittlicher Marktanteil von „Deutschland sucht den Superstar“ (RTL) bei den 14- bis 49-jährigen Zuschauern in Prozent 38,2 31,1 25,8 28,7 Quelle: RTL 1. Staffel 2. Staffel 3. Staffel 4. Staffel* *bisherige Shows seit 10. Januar 1170 Verkaufte Sampler „Deutschland sucht den Superstar“ in Tausend bis jetzt 66 160 120 1. Staffel 2. Staffel 3. Staffel 4. Staffel STEFAN GREGOROWIUS / ACTION PRESS GREGOROWIUS / ACTION STEFAN „DSDS“-Juroren Bohlen, Anja Lukaseder, Heinz Henn: Noch keinen neuen Robbie Williams gefunden er Abhörraum in der Münchner „nur abwechslungsreicher“. Er singt jetzt Angefeuert von einer „Bild“-Titelzeile Niederlassung der Plattenfirma Sony auf Deutsch statt auf Englisch. Er hat sich nach der anderen („TV-Skandal des Jah- DBMG ist bis auf den letzten Platz be- eine Band zugelegt. res“), tobte sich nicht nur der Boulevard, setzt mit Musikern, Managern, Plattenbos- Regner will sich neu erfinden und damit sondern auch das Feuilleton genüsslich aus. sen. Es ist ein wichtiger Termin, der oberste schaffen, was keiner seiner „DSDS“-Vor- Schließlich bot sich die glänzende Gele- Musikchef Willy Ehmann ist auch da. Für gänger und mit Ausnahme der No Angels genheit, einen alten Verdacht zu bestäti- ein paar Minuten donnern Rockmelodien auch sonst keiner der deutschen Casting- gen: Jetzt werde deutlich, „dass es RTL aus großen Boxen; nachdem das letzte Stars hinbekommen hat: aus eigener Kraft nicht um Talente, sondern um die profi- Gitarrenriff verklungen ist, lastet für einen ein zweites Album zu machen, das an den table Vermarkung kurzlebiger Fernseh- Moment Stille schwer im Raum – bis Willy Erfolg der ersten Platte wenigstens an- geschöpfe geht“, echauffierte sich etwa die Ehmann zu klatschen beginnt. -

30 Jahre Media Control Nummer 1 Titel 29.08.1977

30 Jahre Media Control Nummer 1 Titel 29.08.1977 - 31.08.2007 Interpret Titel 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent feat. Olivia Candy Shop ABBA One Of Us ABBA Super Trouper Ace Of Base All That She Wants Ace Of Base The Sign Aerosmith I Don't Want To Miss A Thing Afroman Because I Got High a-ha Take On Me Akon Lonely Alexander Free Like The Wind Alexander Take Me Tonight All-4-One I Swear Alphaville Big In Japan Andy Borg Adios amor Anton aus Tirol feat. DJ Ötzi Anton aus Tirol Aqua Barbie Girl ATC Around The World (La La La La La) Atomic Kitten Whole Again Aventura Obsesion Azad feat. Adel Tawil Prison break anthem (ich glaub an dich) Babylon Zoo Spaceman Baccara Sorry, I'm A Lady Backstreet Boys I Want It That Way Backstreet Boys Quit Playing Games (With My Heart) Band Aid Do They Know It's Christmas? Bangles Walk Like An Egyptian Barbra Streisand Woman In Love Bee Gees You Win Again Beyonce & Shakira Beautiful Liar Blondie Heart Of Glass Bloodhound Gang The Bad Touch Bob Sinclar pres. Goleo VI feat. Gary "Nesta" Pine Love Generation Bobby McFerrin Don't Worry, Be Happy Bomfunk MC's Freestyler Boney M. Belfast Boney M. El Lute Boney M. Mary's Boy Child / Oh My Lord Boney M. Rasputin Boney M. Rivers Of Babylon Bonnie Bianco & Pierre Cosso Stay Britney Spears ...Baby One More Time Britney Spears Lucky Bro'Sis I Believe Bruce & Bongo Geil Bruce Springsteen Streets Of Philadelphia Bryan Adams (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams & Rod Stewart & Sting All For Love C & C Music Factory featuring Freedom Williams Gonna Make You Sweat (Everybody Dance Now) Captain Hollywood Project More And More Celine Dion My Heart Will Go On Ch!pz Cowboy Charles & Eddie Would I Lie To You? Cher Believe Chris Norman Midnight Lady Christian Es ist geil ein Arschloch zu sein Christina Aguilera, Lil' Kim, Mya, Pink Lady Marmalade Cliff Richard We Don't Talk Anymore Clout Substitute Coolio featuring L.V. -

Bernd Clüver 14.05.197310 Get Down

# 1 - Hits Deutschland - Singles 1971 - 2018 1971 GB US 04.01.19714 A Song Of Joy ... Miguel Rios 16 14 01.02.197110 My Sweet Lord ... George Harrison 1 1 12.04.19715 * Rose Garden ... Lynn Anderson 3 3 19.04.19711 Hey Tonight ... Creedence Clearwater Revival 24.05.197115 * Butterfly ... Danyel Gérard 11 78 30.08.19717 * Co-Co ... The Sweet 2 99 25.10.19712 Borriquito ... Peret 08.11.197110 Mamy Blue ... Pop Tops 35 57 1972 GB US 17.01.19721 (Is This The Way To) Amarillo ... Tony Christie 18 24.01.19724 Du Lebst In Deiner Welt (Highlights Of My Dreams) ... Daisy Door 21.02.19723 * Sacramento (A Wonderful Town) ... Middle Of The Road 23 06.03.19722 * Komm, Gib Mir Deine Hand ... Tony Marshall 27.03.19728 How Do You Do ... Windows 22.05.19721 Am Tag, Als Conny Kramer Starb ... Juliane Werding 29.05.19725 * Beautiful Sunday ... Daniel Boone 21 15 05.06.19722 * Es Fährt Ein Zug Nach Nirgendwo ... Christian Anders 17.07.19722 * Michaela ... Bata Illic 24.07.19721 Metal Guru ... T. Rex 1 07.08.19728 * Hello-a ... Mouth & Macneal 14.08.19721 Little Willy ... The Sweet 4 3 09.10.19723 Popcorn ... Hot Butter 5 9 30.10.19728 Wig-Wam Bam ... The Sweet 4 25.12.19729 Ich Wünsch' Mir 'ne Kleine Miezekatze ... Wums Gesang 1973 GB US 26.02.19734 * Blockbuster ... The Sweet 1 73 19.03.19733 * Mama Loo ... Les Humphries Singers 16.04.19734 Der Junge Mit Der Mundharmonika ... Bernd Clüver 14.05.197310 Get Down ..