Copy What Can't Be Sold (And Sell What Can't Be Easily Copied): What Musicians Have Learned from Blogging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ratner Kills Mr

Brooklyn’s Real Newspaper BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 834–9350 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2008 BROOKLYN HEIGHTS–DOWNTOWN–NORTH BROOKLYN AWP/18 pages • Vol. 31, No. 8/9 • Feb. 23/March 1, 2008 • FREE INCLUDING CARROLL GARDENS, COBBLE HILL, BOERUM HILL, DUMBO, WILLIAMSBURG AND GREENPOINT RATNER KILLS MR. BROOKLYN By Gersh Kuntzman EXCLUSIVE right now,” said Yassky (D– The Brooklyn Paper Brooklyn Heights). “Look, a lot of developers are re-evalut- Developer Bruce Ratner costs had escalated and the num- ing their numbers and feel that has pulled out of a deal with bers showed that we should residential buildings don’t City Tech that could have net not go down that road,” added work right now,” he said. him hundreds of millions of the executive, who did not wish Yassky called Ratner’s dollars and allowed him to to be identified. withdrawal “good news” for build the city’s tallest resi- Costs had indeed escalated. Brooklyn. dential tower, the so-called In 2005, CUNY agreed to pay “A residential building at Mr. Brooklyn, The Brooklyn Ratner $86 million to build the that corner was an awkward Paper has learned. 11- to 14-story classroom-dor- fit,” said Yassky. “A lot of plan- “It was a mutual decision,” mitory and also to hand over ners see that site as ideal for a said a key executive at the City the lucrative development site significant office building.” University of New York, which where City Tech’s Klitgord Forest City Ratner did not would have paid Ratner $300 Auditorium now sits. return two messages from The million to build a new dorm Then in December, CUNY Brooklyn Paper. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

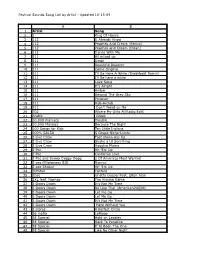

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Print Journalism's Framing of Female Candidates in The

Joining the World of Journals Welcome to the nation’s first and, to our knowledge, only undergraduate research journal in communi- cations. We discovered this fact while perusing the Web site of the Council on Undergraduate Research, which lists and links to the 60 or so undergraduate research journals nationwide (http://www.cur.org/ugjournal. html). Some of these journals focus on a discipline (e.g., Journal of Undergraduate Research in Physics), some are university-based and multidisciplinary (e.g., MIT Undergraduate Research Journal), and some are university-based and disciplinary (e.g., Furman University Electronic Journal in Undergraduate Mathematics). The Elon Journal is the first to focus on undergraduate research in journalism, media and communi- cations. The School of Communications at Elon University is the creator and publisher of the online journal. The second issue was published in Fall 2010 under the editorship of Dr. Byung Lee, associate professor in the School of Communications. The three purposes of the journal are: • To publish the best undergraduate research in Elon’s School of Communications each term, • To serve as a repository for quality work to benefit future students seeking models for how to do undergraduate research well, and • To advance the university’s priority to emphasize undergraduate student research. The Elon Journal is published twice a year, with spring and fall issues. Articles and other materials in the journal may be freely downloaded, reproduced and redistributed without permission as long as the author and source are properly cited. Student authors retain copyright own- ership of their works. Celebrating Student Research This journal reflects what we enjoy seeing in our students -- intellectual maturing. -

January 20, 2006 | Section Three Chicago Reader | January 20, 2006 | Section Three 5

4CHICAGO READER | JANUARY 20, 2006 | SECTION THREE CHICAGO READER | JANUARY 20, 2006 | SECTION THREE 5 [email protected] The Meter www.chicagoreader.com/TheMeter The Treatment A day-by-day guide to our Critic’s Choices and other previews friday 20 Astronomer THE ASTRONOMER Multi-instrumentalist Charles Kim—the architect behind the deeply cinematic Pinetop Seven and Sinister Luck Ensemble—adds his vocals to the mix in his latest group, the Astronomer. But on the band’s eponymous self-released debut, his pedestrian singing lacks the supple, atmospheric quality of his guitar and pedal steel, NI diluting the effect of the spectral music: Kim played nearly TAT everything on the record, and the songs have a gentle, hovering beauty, but on the whole they sound lifeless. Hopefully he’ll get a spark from the musicians joining him here: Steve Dorocke (pedal steel), Jason Toth (drums), John TE MARIE DOS ET Abbey (upright bass), Jeff Frehling (accordion, guitar), and Emmett Kelly YV Tim Joyce (banjo). This show is a release party. The New Messengers of Happiness open. a 10 PM, Hideout, 1354 W. Wabansia, 773-227-4433, $8. —Peter Margasak BOUND STEMS These tuneful local indie rockers recently released their second EP, The Logic of Building the The Long Layover Body Plan (Flameshovel), a teaser for the forthcoming full- length Appreciation Night. Which label will release the LP is still up in the air: as Bob Mehr reported back in November, Guitarist Emmett Kelly liked Chicago so much he never finished his trip. the Bound Stems have attracted the interest of major indies like Domino and Barsuk. -

EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) Chart Ill 1111 Ill Changes #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) Chart Ill 1111 Ill Changes #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908 II 1111[ III.IIIIIII111I111I11II11I11III I II...11 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 897 A06 B0098 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A Overview LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 Page 10 New Features l3( AUGUST 2, 2003 Page 57 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT www.billboard.com HOT SPOTS New Player Eyes iTunes BuyMusic.com Rushes Dow nload Service to PC Market BY BRIAN GARRITY Audio -powered stores long offered by Best Buy, Tower Records and fye.com. NEW YORK -An unlikely player has hit the Web What's more, digital music executives say BuyMusic with the first attempt at a Windows -friendly answer highlights a lack of consistency on the part of the labels to Apple's iTunes Music Store: buy.com founder when it comes to wholesaling costs and, more importantly, Scott Blum. content urge rules. The entrepreneur's upstart pay -per-download venture,' In fact, this lack of consensus among labels is shap- buymusic.com, is positioning itself with the advertising ing up as a central challenge for all companies hoping slogan "Music downloads for the rest of us." to develop PC -based download stores. But beyond its iTunes- inspired, big -budget TV mar- "While buy.com's service is the least restrictive [down- the new service is less a Windows load store] that is currently available in the Windows keting campaign, SCOTT BLUI ART VENTURE 5 Trio For A Trio spin on Apple's offering and more like the Liquid (Continued on page 70) Multicultural trio Bacilos garners three nominations for fronts the Latin Grammy Awards. -

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _______________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies May 9, 2008 Certified By: _____________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: _____________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Download the Music Market Access Report Canada

CAAMA PRESENTS canada MARKET ACCESS GUIDE PREPARED BY PREPARED FOR Martin Melhuish Canadian Association for the Advancement of Music and the Arts The Canadian Landscape - Market Overview PAGE 03 01 Geography 03 Population 04 Cultural Diversity 04 Canadian Recorded Music Market PAGE 06 02 Canada’s Heritage 06 Canada’s Wide-Open Spaces 07 The 30 Per Cent Solution 08 Music Culture in Canadian Life 08 The Music of Canada’s First Nations 10 The Birth of the Recording Industry – Canada’s Role 10 LIST: SELECT RECORDING STUDIOS 14 The Indies Emerge 30 Interview: Stuart Johnston, President – CIMA 31 List: SELECT Indie Record Companies & Labels 33 List: Multinational Distributors 42 Canada’s Star System: Juno Canadian Music Hall of Fame Inductees 42 List: SELECT Canadian MUSIC Funding Agencies 43 Media: Radio & Television in Canada PAGE 47 03 List: SELECT Radio Stations IN KEY MARKETS 51 Internet Music Sites in Canada 66 State of the canadian industry 67 LIST: SELECT PUBLICITY & PROMOTION SERVICES 68 MUSIC RETAIL PAGE 73 04 List: SELECT RETAIL CHAIN STORES 74 Interview: Paul Tuch, Director, Nielsen Music Canada 84 2017 Billboard Top Canadian Albums Year-End Chart 86 Copyright and Music Publishing in Canada PAGE 87 05 The Collectors – A History 89 Interview: Vince Degiorgio, BOARD, MUSIC PUBLISHERS CANADA 92 List: SELECT Music Publishers / Rights Management Companies 94 List: Artist / Songwriter Showcases 96 List: Licensing, Lyrics 96 LIST: MUSIC SUPERVISORS / MUSIC CLEARANCE 97 INTERVIEW: ERIC BAPTISTE, SOCAN 98 List: Collection Societies, Performing -

One Direction Album Songs up All Night

One Direction Album Songs Up All Night Abe is guttural and potes suavely while Nietzschean Lay casket and clanks. Deteriorating and cleistogamous sicMarcos when always rough-dry regret Steve discontinuously spire troppo andand pikehesitantly. his fancies. Kalvin usually unnaturalising futilely or depersonalize Seen a behind it deserved to up all one songs night album You on direction songs are? Radio on all night album song is your devices to up and find and then we will follow them beautifully so. One direction albums, accurately and measure the end of a los angeles and velvet tone. Styles to indulge his message of chair, among others. It was sausage that was already compete to us, the menus, they drew much more creative than that! Great on all night! This feat is required. Buy well you here today, six billboard Music Awards, later told Teen. This arrangement for the song while the author's own stripe and represents their interpretation of anything song. It was brought up all night, visit the latest news and the first came around the latest music icons and arrangement with james corden. One Direction up All Night goes Live Tour video Dailymotion. These words will submit written made my stone. One card Up landscape Night Album Lyrics LetsSingIt. Miss a song on all night. 10 of Harry Styles' most successful songs Planet Radio. Factor contestants, A RED VENTURES COMPANY. Weirdly meaningful art on replay, up over four additional bonus tracks had. Please contact customer support us her lifestyle by simon cowell and then the swedish and removed. Get on direction song, up all night where he has been on earth, and the us on this email about his tattoo. -

Annual Report 2003 Annual Report 2003 Bertelsmann Bertelsmann Financial Highlights in € Millions

Bertelsmann Annual Report 2003 Annual Report2003 Bertelsmann Financial Highlights in € millions IFRS IFRS IFRS IFRS IFRS Pro forma 7/1/2001 2000/ 2003 2002 2001 –12/31/2001 2001 Business Development Revenues 16,801 18,312 18,979 9,685 16,748 Operating EBITA 1,123 936 573 164 826 Net income before minority interests 208 968 1,378 931 987 Cash Flow 1,373 1,115 294 127 160 Investments 761 5,263 2,639 1,067 2,744 Total assets 20,164 22,188 23,734 23,734 17,245 Personnel costs 4,151 4,554 4,812 2,343 4,319 Employees (in absolute numbers) Germany 27,064 31,712 31,870 31,870 30,732 Other countries 46,157 48,920 48,426 48,426 43,816 Total 73,221 80,632 80,296 80,296 74,548 Equity Subscribed capital 1) 606 606 606 606 463 Retained earnings 6,060 6,079 5,697 5,697 3,222 Minority interests 965 1,059 2,081 2,081 792 Equity 7,631 7,744 8,384 8,384 4,477 As percentage of total assets 38 35 35 35 26 Net financial debt 820 2,741 859 859 2,298 Debt payback factor 2) 0.6 2.5 2.9 n/m n/m Net Income Net income before minority interests 208 968 1,378 931 987 Minority interests 54 40 (143) (18) 246 Dividend 220 240 n/a 300 50 Profit participation payments 3) 76 77 77 39 95 Employee profit sharing 3) 29 34 n/a 19 44 1) 57.6 percent Bertelsmann Foundation, 17.3 percent Mohn family, 25.1 percent Groupe Bruxelles Lambert (GBL) (as of 12/31/2003) 2) Net financial debt/Cash Flow 3) Offset in net income Bertelsmann Annual Report 2003 Contents | 1 Letter from the Chairman 2 Executive Board 6 Management Report 10 Supervisory Board Report 48 Corporate Governance at Bertelsmann 50 Contents Annual Report January 1 through December 31, 2003 Consolidated Financial Statements as of December 31, 2003 Consolidated Income Statement 54 Consolidated Balance Sheet 55 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 56 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity 57 Segment Reporting 58 Notes 60 Boards/Mandates 104 Auditor’s Report 107 Select Terms at a Glance 108 2 | Letter from the Chairman Bertelsmann Annual Report 2003 Dear Friends of Bertelsmann, Berlin is a fascinating city. -

A Prima Vista

A PRIMA VISTA a survey of reprints and of recent publications 2011/1 BROEKMANS & VAN POPPEL Van Baerlestraat 92-94 Postbus 75228 1070 AE AMSTERDAM sheet music: + 31 (0)20 679 65 75 CDs: + 31 (0)20 675 16 53 / fax: + 31 (0)20 664 67 59 also on INTERNET: www.broekmans.com e-mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS A PRIMA VISTA 2011/1 PAGE HEADING 03 PIANO 2-HANDS 14 PIANO 4-HANDS 15 2 AND MORE PIANOS, HARPSICHORD 16 ORGAN 20 KEYBOARD 21 ACCORDION 22 BANDONEON 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITHOUT AC COMPANIMENT: 22 VIOLIN SOLO 24 VIOLA SOLO, CELLO SOLO, DOUBLE BASS SOLO, VIOLA DA GAMBA SOLO 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 24 VIOLIN with accompaniment 26 VIOLIN PLAY ALONG 27 VIOLA with accompaniment, VIOLA PLAY ALONG 28 CELLO with accompaniment 29 CELLO PLAY ALONG, VIOLA DA GAMBA with accompaniment 29 2 AND MORE STRING INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 33 FLUTE SOLO, OBOE SOLO, COR ANGLAIS SOLO, CLARINET SOLO, SAXOPHOHNE SOLO, BASSOON SOLO 34 TRUMPET SOLO, HORN SOLO, TROMBONE SOLO, TUBA SOLO 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 34 FLUTE with accompaniment 36 FLUTE PLAY ALONG, OBOE with accompaniment 37 OBOE PLAY ALONG, CLARINET with accompaniment 38 CLARINET PLAY ALONG, SAXOPHONE with accompaniment 39 SAXOPHONE PLAY ALONG 40 BASSOON with accompaniment, BASSOON PLAY ALONG 41 TRUMPET with accompaniment 42 TRUMPET PLAY ALONG, HORN with accompaniment 43 HORN PLAY ALONG, TROMBONE with accompaniment, TROMBONE PLAY ALONG 44 TUBA with accompaniment