1990-1991. Catalog. Hope College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kalamazoo College W.E. Upjohn Center for the Study Of

This digital document was prepared for Kalamazoo College by the W.E. Upjohn Center for the Study of Geographical Change a division of Western Michigan University College of Arts and Sciences COPYRIGHT NOTICE This is a digital version of a Kalamazoo College yearbook. Kalamazoo College holds the copyright for both the paper and digital versions of this work. This digital version is copyright © 2009 Kalamazoo College. All rights reserved. You may use this work for your personal use or for fair use as defined by United States copyright law. Commercial use of this work is prohibited unless Kalamazoo College grants express permission. Address inquiries to: Kalamazoo College Archives 1200 Academy Street Kalamazoo, MI 49006 e-mail: [email protected] .Ko\aVV\ti.XOO Co\\ege. ~a\C\mazoo \ V'f\~c."'~g~V\ Bubbling over, Steaming hot Our Indian name t-Jolds likely as not: Kalamazoo Is a Boiling Pot, Where simmering waters Slowly rise, Then nearly burst The cauldron's sides ; And where, after all, The aim and dream Bubbling, all in a turmoil, unquestionably alive, Is sending the lukewarm the Kalamazoo Coll ege program in the academic Up in steam. year 1963-64 has resembled nothing so much as M. K. a great cauldron of simmering water coming to a rolling boil. Much of the credit for this new energy and activity belongs to President Weimer K. Hicks, to whom, in this tenth year of his asso ciation with the College, this edition of the Boiling Pot is dedicated. MCod~m \ cs ACt '\Vi ti ~s Dff Cam?V0 Sports 0e\\\OrS \Jr\der c\o~~J\\e,r\ Summer Summer employment for caption writers. -

Depauw University Catalog 2007-08

DePauw University Catalog 2007-08 Preamble .................................................. 2 Section I: The University................................. 3 Section II: Graduation Requirements .................. 8 Section III: Majors and Minors..........................13 College of Liberal Arts......................16 School of Music............................. 132 Section IV: Academic Policies........................ 144 Section V: The DePauw Experience ................. 153 Section VI: Campus Living ............................ 170 Section VII: Admissions, Expenses, Aid ............. 178 Section VIII: Personnel ................................ 190 This is a PDF copy of the official DePauw University Catalog, 2007-08, which is available at http://www.depauw.edu/catalog . This reproduction was created on December 17, 2007. Contact the DePauw University registrar, Dr. Ken Kirkpatrick, with any questions about this catalog: Dr. Ken Kirkpatrick Registrar DePauw University 313 S. Locust St. Greencastle, IN 46135 [email protected] 765-658-4141 Preamble to the Catalog Accuracy of Catalog Information Every effort has been made to ensure that information in this catalog is accurate at the time of publication. However, this catalog should not be construed as a contract between the University and any person. The policies contained herein are subject to change following established University procedures. They may be applied to students currently enrolled as long as students have access to notice of changes and, in matters affecting graduation, have time to comply with the changes. Student expenses, such as tuition and room and board, are determined each year in January. Failure to read this bulletin does not excuse students from the requirements and regulations herein. Affirmative Action, Civil Rights and Equal Employment Opportunity Policies DePauw University, in affirmation of its commitment to excellence, endeavors to provide equal opportunity for all individuals in its hiring, promotion, compensation and admission procedures. -

News from HOPE COLLEGE October 2004

Oct04_wrapAround 10/19/04 10:19 AM Page 1 PUBLISHED BY HOPE COLLEGE, HOLLAND, MICHIGAN 49423 news from HOPE COLLEGE October 2004 “Your help is needed now to successfully complete Legacies: A Vision of Hope, and will sustain Hope’s excellence in undergraduate higher education for years to come. Your gift will enhance the worth of every Hope degree, and will make a difference in the lives of generations of students yet to know the value of the Hope experience.” — Dr. James E. Bultman, President Hope College Non-Profit 141 E. 12th St. Organization Holland, MI 49423 U.S. Postage PAID CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED Hope College Oct04_wrapAround 10/19/04 10:19 AM Page 2 Legacies: A Vision of Hope Four cornerstones With four major initiatives, the Legacies: A Vision of Hope campaign is affecting every department and every student. SCIENCE: To build a new science center and renovate the Peale Science Center ENDOWMENT: To increase the endowment to provide ongoing support for college operations and programs DEVOS FIELDHOUSE: To help meet spectator facility needs for the college and Holland MARTHA MILLER CENTER FOR GLOBAL COMMUNICATION: To build a new academic building for multiple departments More about each initiative can be found in the remainder of this four-page campaign supplement. The Science Center Hope is ranked among the nation’s top schools for undergraduate research and creative projects in the America’s Best Colleges guide published by U.S. News and World Report. The building continues Hope’s traditional emphasis on research-based learning. The new building and renovated Peale together more than double the size of Peale alone. -

Faculty Staff Listing

HOPE COLLEGE | FACULTY STAFF Allis, Dr. Jim FACULTY STAFF Retired Faculty Ph.D., University of Pittsburgh, 1986 LISTING M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1984 M.A., New Jersey City University, 1980 M.Ed., Harvard University, 1980 B.A., Dartmouth College, 1975 Aalderink, Linnay Custodian Allore-Bertolone, Shari Assistant Professor of Nursing Instruction Aay, Dr. Henk Senior Research Fellow MSN, Grand Valley State University, 1992 BSN, Grand Valley State University, 1986 Abadi, Zoe Philanthropy Assistant Altamira, Rick Campus Safety Officer Abrahantes, Dr. Miguel Professor of Engineering, Department Chair Anaya, Abraham Ph.D., Universidad Nacional del Sur, 2000 Lab Manager B.S., Universidad Central Las Villas, 1993 Anderson, Dr. Isolde Retired Faculty Achterhof, Todd Dispatcher Ph.D., Northwestern University, 2002 M.Div., North Park Theological Sem, 1981 Adkins, Matt B.A., Smith College, 1975 External Relations and Program Director MBA, University of Baltimore, 2015 Anderson, Robert B.A., Hope College, 2006 Associate Vice President for Principal and Planned Giving Afrik, Robyn Adjunct Faculty Anderson, Shawn B.S., Cornerstone University, Lecturer/Computer Science M.S., Michigan State University, 2016 André, Dr. María Retired Faculty Akansiima, Ivan Ph.D., SUNY University at Albany, 1995 Alberg, Cindy B.A., Universidad del Salvador, 1982 Adjunct Faculty B.A., Hope College, 1992 Armstong, Rebecca Alberg, Erik Arnold, Shelly Technical Director of the Performing Arts Office Manager MFA, University of Delaware, B.A., Hope College, 2014 B.A., Hope College, 1990 Asamoa-Tutu, Austin Director of Hope Entrepreneurship Initiative Alleman, Joshua Grounds-Sports Turf Assistant 1 HOPE.EDU/CATALOG | 2021 - 2022 CATALOG HOPE COLLEGE | FACULTY STAFF Ashdown, Jordan Bach, Jane Lecturer/Kinesiology Retired Faculty M.S., Desales University, 2017 B.A., Hope College, M.A., University of Wisconsin, Aslanian, Janice Ph.D., University of Notre Dame, Retired Faculty M.S., Univ Southern California, 1976 Bade, Dr. -

January 17, 2019 Dear Writer/Publicist: I Invite You to Enter

Great Lakes Colleges Association 535 West William, Suite 301 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48103 U.S.A. PHONE: 734.661.2350 FAX: 734.661.2349 www.glca.org January 17, 2019 Dear Writer/Publicist: I invite you to enter the Great Lakes Colleges Association (GLCA) New Writers Awards (NWA) 2020 competition for poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction. In each category, the submitted work must be an author’s first published volume. For this year’s competition the GLCA will accept entries that bear a publication imprint of 2018 or 2019. Winning writers are announced in January 2020. For the 50th year this group of thirteen independent Midwestern colleges will confer recognition on a volume of writing in each of three literary genres: poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction. Publishers submit works on behalf of their authors; the key criterion for this award is that any work submitted must be an author’s first-published volume in the genre. All entries must be written in English and published in the United States or Canada. Judges of the New Writers Award are professors of literature and creative writing at GLCA member colleges. The winning authors tour several of GLCA’s member colleges from which they receive invitations, giving readings, lecturing, visiting classes, conducting workshops, and publicizing their books. Because of this provision of the award, all writers must live in the U.S. or Canada. Each writer receives an honorarium of at least $500 from each college visited, as well as travel expenses, hotel accommodations, and hospitality. By accepting the award the winner is committed to visit member colleges that extend invitations. -

News from Hope College, Volume 31.6: June, 2000 Hope College

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons News from Hope College Hope College Publications 2000 News from Hope College, Volume 31.6: June, 2000 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/news_from_hope_college Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Hope College, "News from Hope College, Volume 31.6: June, 2000" (2000). News from Hope College. 151. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/news_from_hope_college/151 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Hope College Publications at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in News from Hope College by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Season in Reflections Inside This Issue Review on Year One Outstanding Professor ................... 2 Art in the Family .............................. 3 Psych Alumni Confer .................... 12 TV Game Fame .............................. 16 Please see Please see page 14. page 24. PUBLISHED BY HOPE COLLEGE, HOLLAND, MICHIGAN 49423 news from HOPE COLLEGE June 2000 Beginnings and Returns More than 500 seniors started their post–Hope journeys. Nearly 1,000 alumni already on theirs came back. In either case, the weekend of May 5–7 was a chance to celebrate in a place with meaning and with friends who understood. Please see pages five through 11. Hope College Non-Profit 141 E. 12th St. Organization Holland, MI 49423 U.S. Postage PAID ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED Hope College Campus Notes Graham Peaslee receives H.O.P.E. Award 1993. He was the first recipient from either the department Dr. Graham Peaslee has been of chemistry or the department of geological and presented the 36th annual “Hope environmental sciences to receive the honor. -

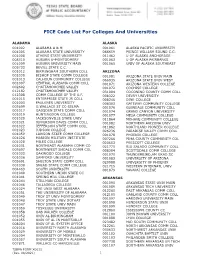

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

2021-2022 Academic Profile Southwest Christian School | CEEB #442562

2021-2022 Academic Profile Southwest Christian School | CEEB #442562 Lakeside Campus The School 2021-2022 Enrollment *as of Sept. 8 6901 Altamesa Blvd. Southwest Christian School (SCS) is an Total Enrollment: 879 Fort Worth, TX 76123 independent, interdenominational, Pre-K Division: 75 817.294.9596 Christian college preparatory school. Elementary Division: 338 Fax: 817.294.9603 Founded in 1969, SCS offers classes in Middle School Division: 137 the divisions of Pre-K, Elementary School (K-Grade 6), Middle School High School Division: 329 Chisholm Trail Campus (Grades 7-8) and High School (Grades Senior Class: 90 6801 Dan Danciger Road 9-12). The Chisholm Trail Campus Fort Worth, TX 76133 accommodates students in Pre-K 817.294.0350 through Grade 6. Students in Grades Faculty Profile 7-12 attend classes at the Lakeside Fax: 817.289.3590 Campus. SCS does not modify The Southwest Christian School curriculum. However, academic faculty is composed of dedicated, support services are available to well-educated professionals. All southwestchristian.org students with diagnosed learning building administrators and differences. SCS nurtures the executive leadership hold advanced development of interests through degrees. The instructional staff for opportunities in advanced academics, the Lakeside Campus includes more Brian Johnson, M.Ed., M.B.A. athletics, fine arts, organizations, than 60% holding or pursuing leadership, and community service, all President / Head of School advanced degrees. in an atmosphere of Christian values. Craig Smith, B.A. Accreditation Associate Head of School Cognia/AdvancED Memberships National Association of Independent Joey Richards, Ed.D. Admission Requirements Schools (NAIS) Associate Head of School Southwest Christian School is Texas Association of Private and committed to diversity and actively Parochial Schools (TAPPS) Somer Yocom, Ed.D. -

News from Hope College, Volume 15.4: February, 1984 Hope College

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons News from Hope College Hope College Publications 1984 News from Hope College, Volume 15.4: February, 1984 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/news_from_hope_college Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Hope College, "News from Hope College, Volume 15.4: February, 1984" (1984). News from Hope College. 53. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/news_from_hope_college/53 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Hope College Publications at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in News from Hope College by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. inside also inside Ode to a basketball team The boob-tube Pollsters inspire poets as Van Wieren’s Hoopsters win #1 nationwide rating scholar behind The varied symptoms of Potomac fever Alumni from Hope’s most active chapter tell Hope’s new film about living in D.C. More TV, more radio, more ink, more fans, more noise Is there anything else to be said about the Hope- Calvin rivalry? Getting by with a little help from friends Hope scientists build valuable ties with big business Quote, Un- CAMPUS NOTES quote is an selective sampling of things being said at and about Hope. From a column by Gretchen Acker- mann in a Dearborn Heights, Mich., newspaper:"Son Brad has decided to open our home on New Year's Eve to a gala party for his fraternitybrothers — the Knickbackers (sic) of Hope College, class of 1980-81. -

2012-13 Academic Catalog

Academic Catalog 2012-13 Table of Contents Academic Calendar Accreditation and Compliance Statements Alma College in Brief Section I: General Information A College of Distinction Admission Information Accelerated Programs and Advanced Placement Options Scholarships and Financial Assistance College Expenses Living on Campus College Regulations The Judicial Process The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and Alma Academic Support Facilities Specialized Services Section II: Academic Programs and Opportunities Requirements for Degrees General Education Goals Guide to General Education Distributive Requirements Academic Honors Faculty Recognition Academic Rules and Procedures Honors Program Interdisciplinary Programs Leadership Programs Pre-Professional Programs Off Campus Study Programs Section III: Courses of Instruction Courses of Instruction Guide to Understanding Course Listings General Studies American Studies (AMS) Art and Design (ART) Astronomy (AST) Biochemistry (BCM) Biology (BIO) Biotechnology (BTC) Business Administration (BUS) Health Care Administration (HCA) International Business Administration (IBA) Chemistry (CHM) Cognitive Science (COG) Communication (COM) Computer Science (CSC) Economics (ECN) Education (EDC) English (ENG) Environmental Studies (ENV) Foreign Service (FOR) Geography (GGR) Geology (GEO) Gerontology (GER) History (HST) Integrative Physiology and Health Science (IPH) Athletic Training (ATH) Public Health (PBH) Library Research (LIB) Mathematics (MTH) Modern Languages French (FRN) German (GRM) Spanish (SPN) -

Inside: 125 Defining Moments Save-The-Date — Celebrating 125 Years Accents Winter 2011

Alma College Alumni Magazine News and Events for Winter 2011 Inside: 125 Defining Moments Save-the-date — Celebrating 125 years accents Winter 2011 editor Mike Silverthorn designers Beth Pellerito Aimee Bentley photographer Skip Traynor printing Millbrook Printing contributors Jeff Abernathy Ellen Doepke 125 years Susan Heimburger Jeff Leestma ’78 As the campus contemplates its direction for the 125 years is a very long time. alumni notes compiled by decades to come, I have been reflecting a great But those same founders would find in the Alma Dolly Van Fossan ’11 deal on the 125 years of Alma’s history. What of today the very same values that led them to would our founders think if they were to see the found our campus in the first place. They would board of trustees Alma of today? Candace Croucher Dugan, Chair see a much larger campus than they envisioned Ron R. Sexton ’68, Vice Chair I’m convinced they would be gratified to find in 1886, but they would find a residential, liberal Larry R. Andrus ’72, Secretary the essential values that led them to take up the arts college deeply familiar to them at the same Bruce T. Alton timber magnate Ammi Wright’s offer of 30 acres time. They would find a college that helps C. David Campbell ’75 of land in the middle of the Lower Peninsula — its students to prepare for lives of service and David K. Chapoton ’57 James C. Conboy Jr. fairly isolated country in those days! — are with engagement in community in myriad ways, a Gary W. -

2019 Recruiter Contact Information

SCHEDULE OF EVENTS SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2019 8:00 AM ARRIVAL AND POSTER SETUP Vande Woude Sessions Conference Room and Cook-Hauenstein Hall 8:15 AM RECRUITER ARRIVAL AND SETUP DeVos Lobby 9:00 AM WELCOME Tomatis Auditorium Steve Triezenberg, PhD Dean, Van Andel Institute Graduate School and WMRUGS Master of Ceremonies 9:15 AM KEYNOTE SPEAKER ADDRESS Tomatis Auditorium Paloma Vargas, PhD Assistant Professor of Biology and Director, Hispanic-Serving Institute Initiatives California Lutheran University “Learning Through Research: Life Lessons from a Latinx Biologist” 10:00 AM POSTER SESSION I Vande Woude Sessions Conference Room and Cook-Hauenstein Hall Presenters at even-numbered posters 11:25 AM GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH TALK Tomatis Auditorium Zach DeBruine, PhD Candidate – Van Andel Institute Graduate School “Frizzled GPCRs initiate and amplify signaling through independent mechanisms” 11:40 AM UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH TALKS Tomatis Auditorium Svetlana Djirackor, Aquinas College “Subcloning of zebrafish NOD1 alleles into UAS:P2A-nls-EGFP for investigation of NOD1’s role in hematopoietic stem cell development” Liam Ferraby, Calvin University “The Science of Providing Services Spatially for Returning Citizens” 12:10 PM LUNCH Cook-Hauenstein Hall Lunch seating is available in the café, conference rooms 3104 & 3105, the pre-function area outside of conference rooms 3104 & 3105 and Tomatis Auditorium 12:35 PM RECORDED TED TALKS Tomatis Auditorium Please join us in the auditorium to watch recorded TED Talks 1:10 PM POSTER SESSION II