March 2019 CFEL Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribal Handicraft Report

STATUS STUDY OF TRIBAL HANDICRAFT- AN OPTION FOR LIVELIHOOD OF TRIBAL COMMUNITY IN THE STATES OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH RAJASTHAN, UTTARANCHAL AND CHHATTISGARH Sponsored by: Planning Commission Government of India Yojana Bhawan, Sansad Marg New Delhi 110 001 Socio-Economic and Educational Development Society (SEEDS) RZF – 754/29 Raj Nagar II, Palam Colony. New Delhi 110045 Socio Economic and Educational Planning Commission Development Society (SEEDS) Government of India Planning Commission Government of India Yojana Bhawan, Sansad Marg New Delhi 110 001 STATUS STUDY OF TRIBAL HANDICRAFTS- AN OPTION FOR LIVELIHOOD OF TRIBAL COMMUNITY IN THE STATES OF RAJASTHAN, UTTARANCHAL, CHHATTISGARH AND ARUNACHAL PRADESH May 2006 Socio - Economic and Educational Development Society (SEEDS) RZF- 754/ 29, Rajnagar- II Palam Colony, New Delhi- 110 045 (INDIA) Phone : +91-11- 25030685, 25362841 Email : [email protected] Socio Economic and Educational Planning Commission Development Society (SEEDS) Government of India List of Contents Page CHAPTERS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY S-1 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objective of the Study 2 1.2 Scope of Work 2 1.3 Approach and Methodology 3 1.4 Coverage and Sample Frame 6 1.5 Limitations 7 2 TRIBAL HANDICRAFT SECTOR: AN OVERVIEW 8 2.1 Indian Handicraft 8 2.2 Classification of Handicraft 9 2.3 Designing in Handicraft 9 2.4 Tribes of India 10 2.5 Tribal Handicraft as Livelihood option 11 2.6 Government Initiatives 13 2.7 Institutions involved for promotion of Handicrafts 16 3 PEOPLE AND HANDICRAFT IN STUDY AREA 23 3.1 Arunachal Pradesh 23 -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Ethnolinguistic Survey of Westernmost Arunachal Pradesh: a Fieldworker’S Impressions1

This is the version of the article/chapter accepted for publication in Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, 37 (2). pp. 198-239 published by John Benjamins : https://doi.org/10.1075/ltba.37.2.03bod This material is under copyright and that the publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use or reprint the material in any form Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/34638 ETHNOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF WESTERNMOST ARUNACHAL PRADESH: A FIELDWORKER’S IMPRESSIONS1 Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Timotheus Adrianus Bodt Volume xx.x - University of Bern, Switzerland/Tezpur University, India The area between Bhutan in the west, Tibet in the north, the Kameng river in the east and Assam in the south is home to at least six distinct phyla of the Trans-Himalayan (Tibeto-Burman, Sino- Tibetan) language family. These phyla encompass a minimum of 11, but probably 15 or even more mutually unintelligible languages, all showing considerable internal dialect variation. Previous literature provided largely incomplete or incorrect accounts of these phyla. Based on recent field research, this article discusses in detail the several languages of four phyla whose speakers are included in the Monpa Scheduled Tribe, providing the most accurate speaker data, geographical distribution, internal variation and degree of endangerment. The article also provides some insights into the historical background of the area and the impact this has had on the distribution of the ethnolinguistic groups. Keywords: Arunachal Pradesh, Tibeto-Burman, Trans-Himalayan, Monpa 1. INTRODUCTION Arunachal Pradesh is ethnically and linguistically the most diverse state of India. -

Prayer-Guide-South-Asia.Pdf

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

Sociolinguistic Research Among Selected Groups in Western Arunachal Pradesh Highlighting Monpa

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2018-009 Sociolinguistic Research among Selected Groups in Western Arunachal Pradesh Highlighting Monpa Binny Abraham, Kara Sako, Elina Kinny, and Isapdaile Zeliang Sociolinguistic Research among Selected Groups in Western Arunachal Pradesh Highlighting Monpa Binny Abraham, Kara Sako, Elina Kinny, and Isapdaile Zeliang SIL International® 2018 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2018-009, August 2018 © 2018 SIL International® All rights reserved Data and materials collected by researchers in an era before documentation of permission was standardized may be included in this publication. SIL makes diligent efforts to identify and acknowledge sources and to obtain appropriate permissions wherever possible, acting in good faith and on the best information available at the time of publication. Abstract This research was started in November 2003, initially among the Monpa varieties of Western Arunachal Pradesh, India, and was later expanded to Sherdukpen, Chug, Lish, Bugun and Miji because of their geographical proximity. The fieldwork continued until August 2004 with some gaps in between. The researchers were Binny Abraham, Kara Sako, Isapdaile Zeliang and Elina Kinny. The languages studied in this report, all belonging to the Tibeto-Burman family, have the following ISO codes:1 Tawang Monpa [twm], Tshangla (Dirang) [tsj], Kalaktang Monpa [kkf], Sartang (But Monpa) [onp], Sherdukpen [sdp], Hruso (Aka) [hru], (Aka) Koro [jkr], Chug [cvg], Lish [lsh], Bugun [bgg], and Miji [sjl]. [This survey report written some time ago deserves to be made available even at this late date. Conditions were such that it was not published when originally written. The reader is cautioned that more recent research may be available. -

LCSH Section J

J (Computer program language) J. I. Case tractors Thurmond Dam (S.C.) BT Object-oriented programming languages USE Case tractors BT Dams—South Carolina J (Locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) J.J. Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) J. Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) BT Locomotives USE Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) UF Clark Hill Lake (Ga. and S.C.) [Former J & R Landfill (Ill.) J.J. "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) heading] UF J and R Landfill (Ill.) UF "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clark Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) J&R Landfill (Ill.) Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clarks Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) BT Sanitary landfills—Illinois BT Public buildings—Texas Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) J. & W. Seligman and Company Building (New York, J. James Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) BT Lakes—Georgia USE Banca Commerciale Italiana Building (New UF Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Lakes—South Carolina York, N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) Reservoirs—Georgia J 29 (Jet fighter plane) BT Public buildings—Nebraska Reservoirs—South Carolina USE Saab 29 (Jet fighter plane) J. Kenneth Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) J.T. Berry Site (Mass.) J.A. Ranch (Tex.) UF Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) UF Berry Site (Mass.) BT Ranches—Texas BT Post office buildings—Virginia BT Massachusetts—Antiquities J. Alfred Prufrock (Fictitious character) J.L. Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, N.C.) J.T. Nickel Family Nature and Wildlife Preserve (Okla.) USE Prufrock, J. Alfred (Fictitious character) UF Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, UF J.T. -

An Experimental Analysis of Speech Features for Tone Speech Recognition

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-9 Issue-2, December 2019 An Experimental Analysis of Speech Features for Tone Speech Recognition Utpal Bhattacharjee, Jyoti Mannala Abstract: Recently Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) has broad categories - characteristics tone and significance been successfully integrated in many commercial applications. tone. Characteristic tone is the method of grouping of musical These applications are performing significantly well in relatively pitch which characterize a particular language, language controlled acoustical environments. However, the performance of group or language family. Significant tone on the other hand an Automatic Speech Recognition system developed for non-tonal languages degrades considerably when tested for tonal languages. plays an active part in the grammatical significance of the One of the main reason for this performance degradation is the language, may be a means of distinguishing words of non-consideration of tone related information in the feature set of different meaning otherwise phonetically alike. A generally the ASR systems developed for non-tonal languages. In this paper accepted definition of tone language was proposed by K.Pink we have investigated the performance of commonly used feature [5]. According to this definition, a tone language must have for tonal speech recognition. A model has been proposed for lexical constructive tone. In generative phonology, it means extracting features for tonal speech recognition. A statistical analysis has been done to evaluate the performance of proposed tone of a tonal phonemes are no way predictable, must have feature set with reference to the Apatani language of Arunachal to specify in the lexicon of each morpheme [3]. -

Himalayan Linguistics Apatani Phonology and Lexicon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bern Open Repository and Information System (BORIS) Himalayan Linguistics Apatani phonology and lexicon, with a special focus on tone Mark W. Post and Tage Kanno Universität Bern and Future Generations ABSTRACT Despite being one of the most extensively researched of Eastern Himalayan languages, the basic morphological and phonological-prosodic properties of Apatani (Tibeto-Burman > Tani > Western) have not yet been adequately described. This article attempts such a description, focusing especially on interactions between segmental-syllabic phonology and tone in Apatani. We highlight three features in particular – vowel length, nasality and a glottal stop – which contribute to contrastively-weighted syllables in Apatani, which are consistently under-represented in previous descriptions of Apatani, and in absence of which tone in Apatani cannot be effectively analysed. We conclude that Apatani has two “underlying”, lexically-specified tone categories H and L, whose interaction with word structure and syllable weight produce a maximum of three “surface” pitch contours – level, falling and rising – on disyllabic phonological words. Two appendices provide a set of diagnostic procedures for the discovery and description of Apatani tone categories, as well as an Apatani lexicon of approximately one thousand entries. KEYWORDS | downloaded: 13.3.2017 lexicon, tone, morphophonology, Tibeto-Burman languages, Tani languages, Eastern Himalayan languages, Apatani This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 12(1): 17– 75 ISSN 1544-7502 © 2013. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. http://boris.unibe.ch/46374/ Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/HimalayanLinguistics source: Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. -

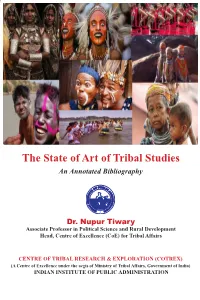

The State of Art of Tribal Studies an Annotated Bibliography

The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs Contact Us: Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration, Indian Institute of Public Administration, Indraprastha Estate, Ring Road, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi, Delhi 110002 CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) Phone: 011-23468340, (011)8375,8356 (A Centre of Excellence under the aegis of Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) Fax: 011-23702440 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Email: [email protected] NUP 9811426024 The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Edited by: Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) (A Centre of Excellence under Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION THE STATE OF ART OF TRIBAL STUDIES | 1 Acknowledgment This volume is based on the report of the study entrusted to the Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration (COTREX) established at the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA), a Centre of Excellence (CoE) under the aegis of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA), Government of India by the Ministry. The seed for the study was implanted in the 2018-19 action plan of the CoE when the Ministry of Tribal Affairs advised the CoE team to carried out the documentation of available literatures on tribal affairs and analyze the state of art. As the Head of CoE, I‘d like, first of all, to thank Shri. -

35 Chapter 2 INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICTS in NORTH EAST

Chapter 2 INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICTS IN NORTH EAST INDIA India as a whole has about 4,635 communities comprising 2,000 to 3,000 caste groups, about 60,000 of synonyms of titles and sub-groups and near about 40,000 endogenous divisions (Singh 1992: 14-15). These ethnic groups are formed on the basis of religion (Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian, Jain, Buddhist, etc.), sect (Nirankari, Namdhari and Amritdhari Sikhs, Shia and Sunni Muslims, Vaishnavite, Lingayat and Shaivite Hindus, etc.), language (Assamese, Bengali, Manipuri, Hindu, etc.), race (Mongoloid, Caucasoid, Negrito, etc.), caste (scheduled tribes, scheduled castes, etc.), tribe (Naga, Mizo, Bodo, Mishing, Deori, Karbi, etc.) and others groups based on national minority, national origin, common historical experience, boundary, region, sub-culture, symbols, tradition, creed, rituals, dress, diet, or some combination of these factors which may form an ethnic group or identity (Hutnik 1991; Rastogi 1986, 1993). These identities based on religion, race, tribe, language etc characterizes the demographic pattern of Northeast India. Northeast India has 4,55,87,982 inhabitants as per the Census 2011. The communities of India listed by the „People of India‟ project in 1990 are 5,633 including 635 tribal groups, out of which as many as 213 tribal groups and surprisingly, 400 different dialects are found in Northeast India. Besides, many non- tribal groups are living particularly in plain areas and the ethnic groups are formed in terms of religion, caste, sects, language, etc. (Shivananda 2011:13-14). According to the Census 2011, 45587982 persons inhabit Northeast India, out of which as much as 31169272 people (68.37%) are living in Assam, constituting mostly the non-tribal population. -

Title Cultural Adaptation of the Himalayan Ethnic Foods With

Cultural Adaptation of the Himalayan Ethnic Foods with Title Special Reference to Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh Author(s) Tamang, Jyoti Prakash; Okumiya, Kiyohito; Kosaka, Yasuyuki ヒマラヤ学誌 : Himalayan Study Monographs (2010), 11: Citation 177-185 Issue Date 2010-05-01 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/HSM.11.177 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Himalayan Study Monographs No.11, 177-185,Him 2010alayan Study Monographs No.11 2010 Cultural Adaptation of the Himalayan Ethnic Foods with Special Reference to Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh Jyoti Prakash Tamang1), Kiyohito Okumiya2) and Yasuyuki Kosaka2) 1)Food Microbiology Laboratory, Sikkim University, Gangtok 737102, India 2)Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto 603-8047, Japan The Himalayan people have developed the ethnic foods to adapt to the harsh conditions and environment. The in-take of such foods has been in the systems for centuries and people have adapted such foods to protect and sustain them. People living in high altitude (>2500) are adapted to cereals and food grains grown in dry and cold climates, with less vegetables and more meat products. More diversity of food items ranging from rice, maize to vegetable, milk to meat is prevalent in the elevation less than 2500 to 1000 m. Ethnic foods possess protective properties, antioxidant, antimicrobial, probiotics, bio-nutrients, and some important health-benefits compounds. Due to rapid urbanisation, development, introduction of commercial ready-to-eat foods have adverse effects on production and consequently consumption of such age-old cultural ethnic foods is declining. The people should be ascertained about the worth indigenous knowledge they possess, and biological significance of their foods. -

The NEHU Journal, Vol XV, No

ISSN. 0972 - 8406 The NEHU Journal, Vol XV, No. 2, July-December 2017, The NEHU Journal Vol. XV, No. 2, July-December 2017 N E H U ISSN. 0972 - 8406 The NEHU Journal, Vol XV, No. 2, July-December 2017, ISSN. 0972 - 8406 The NEHU Journal Vol. XV, No. 2, July-December 2017 Editor: H. Srikanth Assistant Editor: G. Umdor Editorial Committee Members Dr. A. K. Chandra, Department of Chemistry, NEHU, Shillong Dr. A. K. Thakur, Department of History, NEHU, Shillong Dr. A. P. Pati, Department of Commerce, NEHU, Shillong Dr. Geetika Ranjan, Department of Anthropology, NEHU, Shillong Dr. Jyotirmoy Prodhani, Department of English, NEHU, Shillong Dr. Uma Shankar, Department of Botany, NEHU, Shillong Production Assistant : Surajit Dutta Prepress : S. Diengdoh ISSN. 0972 - 8406 The NEHU Journal, Vol XV, No. 2, July-December 2017, CONTENTS Editorial .... .... v Economic Reforms and Food Security: .... .... 1 Rationale for State Intervention in India V. BIJUKUMAR Nutritional Intake and Consumption .... .... 15 Pattern in the States of Himachal Pradesh and Meghalaya ANIKA M. W. K. SHADAP AND VERONICA PALA Social Audit in Mahatma Gandhi .... .... 29 National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) with Special Reference to Tripura SANJOY ROY Irrigation System and Pattern of Crop .... .... 45 Combination, Concentration and Diversification in Barddhaman District, West Bengal KSHUDIRAM CHAKRABORTY AND BISWRANJAN MISTRI Buddhist ‘Theory of Meaning’ .... .... 67 (Apohavada)- as Negative Meaning SANJIT CHAKRABORTY Negation in Nyishi .... .... 79 MOUMITA DEY ISSN. 0972 - 8406 IV The NEHU Journal, Vol XV, No. 2, July-December 2017, Menstruation Pollution Taboos and .... .... 101 Gender Based Violence in Western Nepal PRAKASH UPADHYAY Knowledge of ICT and Computer ...