In the Shadows of the Himalayan Mountains: Persistent Gender and Social Exclusion 14 in Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

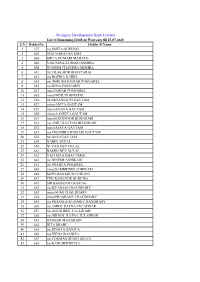

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation Volume 1,September2017 Volume cg'jfbs ;dfh g]kfn Society of Translators Nepal Nepalese Translation Volume 1 September 2017 Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Office bearers for 2016-2018 President Victor Pradhan Vice-president Bal Ram Adhikari General Secretary Bhim Narayan Regmi Secretary Prem Prasad Poudel Treasurer Karuna Nepal Member Shekhar Kharel Member Richa Sharma Member Bimal Khanal Member Sakun Kumar Joshi Immediate Past President Basanta Thapa Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Nepalese Translation is a journal published by Society of Translators Nepal (STN). STN publishes peer reviewed articles related to the scientific study on translation, especially from Nepal. The views expressed therein are not necessarily shared by the committee on publications. Published by: Society of Translators Nepal Kamalpokhari, Kathmandu Nepal Copies: 300 © Society of Translators Nepal ISSN: 2594-3200 Price: NC 250/- (Nepal) US$ 5/- EDITORIAL strategies the practitioners have followed to Translation is an everyday phenomenon in the overcome them. The authors are on the way to multilingual land of Nepal, where as many as 123 theorizing the practice. Nepali translation is languages are found to be in use. It is through desperately waiting for such articles so that translation, in its multifarious guises, that people diverse translation experiences can be adequately speaking different languages and their literatures theorized. The survey-based articles present a are connected. Historically, translation in general bird's eye view of translation tradition in the is as old as the Nepali language itself and older languages such as Nepali and Tamang. than its literature. -

Five Nepali Novels Michael Hutt SOAS, University of London, [email protected]

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 34 | Number 2 Article 6 December 2014 Writers, Readers, and the Sharing of Consciousness: Five Nepali Novels Michael Hutt SOAS, University of London, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Hutt, Michael (2014) "Writers, Readers, and the Sharing of Consciousness: Five Nepali Novels," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 34: No. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol34/iss2/6 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Writers, Readers, and the Sharing of Consciousness: Five Nepali Novels Acknowledgements The uthora wishes to thank the British Academy for funding the research that led to the writing of this paper, and to friends and colleagues at Martin Chautari for helping him in so many ways. He is also grateful to Buddhisgar Chapain, Krishna Dharabasi and Yug Pathak for sparing the time to meet and discuss their novels with him. This research article is available in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol34/iss2/6 Writers, Readers, and the Sharing of Consciousness: Five Nepali Novels Michael Hutt In his seminal book Literature, Popular Culture Urgenko Ghoda and Buddhisagar Chapain’s and Society, Leo Lowenthal argues that studies Karnali Blues) have achieved a high public of the representation of society, state, or profile. -

Writers, Readers, and the Sharing of Consciousness: Five Nepali Novels

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 34 Number 2 Article 6 December 2014 Writers, Readers, and the Sharing of Consciousness: Five Nepali Novels Michael Hutt SOAS, University of London, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Hutt, Michael. 2014. Writers, Readers, and the Sharing of Consciousness: Five Nepali Novels. HIMALAYA 34(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol34/iss2/6 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Writers, Readers, and the Sharing of Consciousness: Five Nepali Novels Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank the British Academy for funding the research that led to the writing of this paper, and to friends and colleagues at Martin Chautari for helping him in so many ways. He is also grateful to Buddhisgar Chapain, Krishna Dharabasi and Yug Pathak for sparing the time to meet and discuss their novels with him. This research article is available in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol34/iss2/6 Writers, Readers, and the Sharing of Consciousness: Five Nepali Novels Michael Hutt In his seminal book Literature, Popular Culture Urgenko Ghoda and Buddhisagar Chapain’s and Society, Leo Lowenthal argues that studies Karnali Blues) have achieved a high public of the representation of society, state, or profile. -

Divident List

Shangrila Development Bank Limited List of Remaining Divident Warrants till 15-07-2020 S.N HolderNo Holder'S Name 1 577 ms.SMITA GURUNG 2 603 YOG NARAYAN SAH 3 604 SHILA KUMARI MAHATO 4 606 VANDANA KUMARI MISHRA 5 608 YOGESH CHANDRA MISHRA 6 612 mr.TILAK BDR BHATTARAI 7 613 ms.ROZINA KARKI 8 615 mr.DHRUBA KUMAR POKHAREL 9 616 ms.NIMA POKHAREL 10 617 minorNIRAB POKHAREL 11 618 minorMINU POKHAREL 12 626 mr.JAGANNATH GAUTAM 13 627 minorANITA GAUTAM 14 629 minorAVAYA GAUTAM 15 630 minorAANKITA GAUTAM 16 631 minorKOHINOOR BHANDARI 17 632 ms.ANJU GAUTAM BHANDARI 18 633 minorAJAYA GAUTAM 19 635 ms.CHANDRA KUMARI GAUTAM 20 636 mr.ANUJ GAUTAM 21 639 NABIN ARYAL 22 640 NUTAN DEV DULAL 23 641 BASHU DEV DULAL 24 642 YACHANA BHATTARAI 25 643 mr.DINESH ADHIKARI 26 644 ms.PRABHA POKHREL 27 645 minorSAMBRIDHI ADHIKARI 28 646 KESH BAHADUR GURUNG 29 647 TEK BAHADUR GURUNG 30 648 SIR BAHADUR GURUNG 31 652 mr.SIYARAM CHAUDHARY 32 653 minorSUMI CHAUDHARY 33 654 minorPRASHANT CHAUDHARY 34 655 ms.PRAMILA KUMARI CHAUDHARY 35 656 mr.AMRIT RATNA TULADHAR 36 657 ms.ANUSHREE TULADHAR 37 658 mr.NIRMAL RATNA TULADHAR 38 663 RAMESH MAHARJAN 39 664 RITA SHAHI 40 665 mr.BINAYA BANIYA 41 666 ms.JEENA BAANIYA 42 667 mr.YOGMAN SINGH DEUJA 43 668 ms.KANCHHI DEUJA 44 670 mr.KRISHNA BDR. BASNET 45 671 ms.ANJALI KHADKA 46 678 mr.MANOJ KUMAR SHAH 47 682 mr.MANOJ KUMAR MANDAL GANGAI 48 689 LAXMI GURUNG 49 690 mr.PADAM RAJ SIGDEL 50 691 ms.JYOTI KHADGI 51 692 RAMHARI BOHARA 52 693 NIRMALA SANGROULA BOHARA 53 694 SAMPADA BOHARA 54 695 mr.LAXMAN PAUDEL 55 696 minorSAMBRIDDHI MAHARJAN 56 698 mr.BUDDHA RATNA MAHARJAN 57 703 GAJENDRA RAJ GHIMIRE 58 713 MAHENDRA PD. -

Writers and Readers in Transitional Nepal Michael Hutt (SOAS, London)

Writers and Readers in Transitional Nepal Michael Hutt (SOAS, London) 1. Introduction The past decade has seen significant changes in the world of Nepali publishing, marketing and reading.1 Ever since literary publishing began in earnest during the 1930s, Nepali literary works have normally been published in editions of no more than 1000 cheaply produced paperbook copies, which often take several years to sell. The vast majority of book sales have been of a small number of classic works such as Lakshmi Prasad Devkota’s narrative poem Muna-Madan (or indeed Parijat’s novel Shirishko Phul, which has sold more than 100,000 copies since its first publication in 1965 (Aryal 2011: 49)). While such works continue to sell, in recent years the Nepali public’s book-buying capacity has increased dramatically, so that the list of books that have sold in excess of 1000 copies is now quite long, and sales of over 10,000 are no longer uncommon. Current best-sellers include Nepali-language novels; books about the Maoist People’s War; books about the Narayanhiti palace massacre; and English language fiction by Nepali authors (notably, Manjushree Thapa and Samrat Upadhyay). Before 2002, probably more than half of the Nepali fiction and poetry in print2 was published by Sajha Prakashan,3 with the rest coming out of the Nepal Academy (Pragya Pratisthan), and a number of small private publishers. Ratna Pustak Bhandar is Nepal’s oldest private publisher and probably the classic example4 but the number of private publishers has grown considerably. For instance, a publisher such as Vivek Srijanshil Prakashan produces ‘progressive’ writings by Nepali and foreign authors in large quantity and at a very low unit price. -

Ghale Language: a Brief Introduction

Nepalese Linguistics Volume 23 November, 2008 Chief Editor: Jai Raj Awasthi Editors: Ganga Ram Gautam Bhim Narayan Regmi Office Bearers for 2008-2010 President Govinda Raj Bhattarai Vice President Dan Raj Regmi General Secretary Balaram Prasain Secretary (Office) Krishna Prasad Parajuli Secretary (General) Bhim Narayan Regmi Treasurer Bhim Lal Gautam Member Bal Mukunda Bhandari Member Govinda Bahadur Tumbahang Member Gopal Thakur Lohar Member Sulochana Sapkota (Bhusal) Member Ichchha Purna Rai Nepalese Linguistics is a Journal published by Linguistic Society of Nepal. This Journal publishes articles related to the scientific study of languages, especially from Nepal. The views expressed therein are not necessarily shared by the committee on publications. Published by: Linguistic Society of Nepal Kirtipur, Kathmandu Nepal Copies: 500 © Linguistic Society of Nepal ISSN – 0259-1006 Price: NC 300/- (Nepal) IC 300/- (India) US$ 6/- (Others) Life membership fees include subscription for the journal. TABLE OF CONTENTS Tense and aspect in Meche Bhabendra Bhandari 1 Complex aspects in Meche Toya Nath Bhatta 15 An experience of translating Nepali grammar into English Govinda Raj Bhattarai 25 Bal Ram Adhikari Compound case marking in Dangaura Tharu Edward D. Boehm 40 Passive like construction in Darai Dubi Nanda Dhakal 58 Comparative study of Hindi and Punjabi language scripts Vishal Goyal 67 Gurpreet Singh Lehal Some observations on the relationship between Kaike and Tamangic Isao Honda 83 Phonological variation in Srinagar variety of Kashmiri -

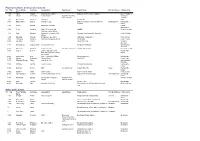

List of Participants

Paper presenters and resource person SN Title First + Middle Surname Designation Department Organization Postal Address City/Country Name 1 Mr. Afzal Abdulla Administrative Officer Department of Heritage, Maldives Male / Maldives 2 Dr. Amara Srisuchat Senior Expert Department of Fine Bangkok / Arts, Thailand Thailand 3 Dr. Arun Kumar Chatterjee Chairman ICOM India India 4 Mr. Bharat Mani Subedi Joint Secretary Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Singha Durbar Kathmandu / Aviation Nepal 5 Mr. Bulbul Ahmed Associate Professor Dhaka / Bangladesh 6 Mr. Celso Coracini Crime Prevention and UNODC Vienna / Austria Criminal Justice Officer 7 Dr. Dina Bangdel Associate Professor of Art Verginia Commonwealth University Doha / Quatar History 8 Mr. Edouard Planche Programme Specialist UNESCO Headquarter Paris / France 9 Mr. Françoise Bortolotti Criminal Intelligence Officer SG Interpol Lyon / France 10 Mr. Gaspare Cilluffo RILO WE-WCO Cologne / Germany 11 Mr. Gundegmaa Jargalsaikhan Secretary General Mongolian NATCOM Ulaanbaatar / Mongolia 12 Mr. Hartley B. Waltman Senior Counsel Art Law Department Christie's New York New York / USA 13 Mr. Jurgen Schick Lawyer and author of the Kathmandu / book 'The gods are leaving Nepal the country' 14 Mr. Kanak Mani Dixit Writer / Journalist / Editor Himal Southasian Kathmandu / 15 Ms. Marina Schneider Senior Officer UNIDROIT Rome / Italy 16 Mr. Mashood Ahmad Mirza Joint Secretary Islamababad / Pakistan 17 Ms. Mathilde Heaton Legal Counsel Chirstie's Hong Kong Hong Kong / China 18 Mr. Narahari Regmi DSP Interpol Section Nepal Police HQ Naxal Kathmandu / Nepal 19 Ms. Nathalie Bazin Chief Curator Musee Guimet, Paris Paris / France 20 Mr. Ram Bahadur Kunwar Chief Archaeological officier Department of Archaeology Ram Shah Path Kathmandu / Nepal 21 Mr. -

Rajan Ghimire, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Rajan Ghimire, Ph.D. New Mexico State University E-mail: [email protected] Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences Office: 575-985-2292 Agricultural Science Center at Clovis Cell: 541-314-1411 2346 State Road 288 www.rghimire.net Clovis, NM 88101 1. EDUCATION Ph.D., Soil Science, 2013, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY Dissertation: Soil organic matter and soil microbial communities in long-term and transitional crop and forage production systems in eastern Wyoming M.Sc. Soil Science, 2016, Tribhuvan University, Nepal Thesis: Soil organic carbon sequestration by tillage, crop residue, and nitrogen management in the light and heavy soils of Chitwan, Nepal B.Sc. Agriculture (Soil Science), 2004, Tribhuvan University, Nepal 2. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Visiting Professor (Jan. 2017 – Dec. 2021), Northwest University, Xian, China Assistant Professor (Oct. 2015 – Date), New Mexico State University, Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, Las Cruces, NM, located at Agricultural Science Center at Clovis, NM Postdoctoral Scholar (Jan. 2014 – Sept. 2015), Oregon State University, Columbia Basin Agricultural Research Center, Pendleton, OR Research Associate (June 2013 – Dec. 2013), University of Wyoming, Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, Laramie, WY Graduate Assistant (Aug. 2009 – May 2013), University of Wyoming, Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, Laramie, WY Visiting Scientist (May – July 2008), Wageningen University and Research Centre/ Louis Bolk Institute, the Netherlands Lecturer of Soil Science (June 2006 – July 2009), Tribhuvan University, Institute of Agriculture and Animal Sciences, Nepal Senior Research Assistant (May 2006 – July 2009), Ecological Services Centre, Nepal. Graduate Assistant (2004 – 2006), Tribhuvan University, Institute of Agriculture and Animal Sciences, Nepal 3. -

571 16 - 22 September 2011 18 Pages Rs 30

#571 16 - 22 September 2011 18 pages Rs 30 BIKRAM RAI Patans literary jatra p8-9 Full program of the Kathmandu Literary Jatra, INSIDE p11 Rabi Thapa on reading between the lines at the Jatra, he historical Patan Darbar Square is hosting a first-time literature festival over the weekend. Next week, a young Nepali woman with cerebral palsy, whose only way of T communicating is by writing with her foot, is being awarded Nepals most More than 30 well known national and international p6-7 writers will hold forth on languages, minority voices, prestigious literary prize, the Madan Puraskar journalism, politics, history and books, books, books. The Nepali translation of Ani Choying Drolmas auto-biography, Singing for They include Akshay Pathak, Alka Saraogi, Jug Suraiya, p16 Freedom, titled Phoolko Ankhama is being launched later this month p11 Namita Gokhale, Shazia Omar, Tarun Tejpal, William Collection of Wayne Amtzis poetry, Quicksand Nation, looks at Nepals war Dalrymple, Mohammed Hanif and our own Abhi p17 Subedi, Anbika Giri, Naryan Wagle, Rabi Thapa and in the context of the unhappy peace that preceded and followed it Sanjeev Uprety, among others. 2 EDITORIAL 16 - 22 SEPTEMBER 2011 #571 REALITY CHECK cross-section of Nepalis we spoke to on a on whether or not to officially split off. The talk of swing through central Nepal this week were revolt now is of a revolt within the party. A unanimous in their support for Baburam With all this going on, the peoples expectations Bhattarai. After months of paralyzing deadlock, on one beleaguered prime minister may be there is hope that the new prime ministers intellect unrealistically high. -

Nepali Times

Subscriber’s copy #183 13 - 19 February 2004 24 pages Rs 25 Weekly Internet Poll # 123 Q. Should foreign ownership of Nepali media be allowed? Total votes:1,062 Weekly Internet Poll # 124. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q. Do you think King Gyanendra overstepped the bounds of a constitutional monarch with the royal address in Nepalganj? 8, going on 9 Twelve-year-old Surendra Shrestha bikes in Tahachal during Thursdays bandh. KUNDA DIXIT He was four when the war started.KIRAN PANDAY s the Maoist war completes palace and the parties, and between Nepalis. These are the harshest Nepali Maoists. eight years, never has peace hawks and doves among Nepals words the Maoists have used against Officially, this sends the seemed as remote. donors. India in the recent past. message that India is no longer safe. Nepalis caught in the middle However, the biggest blow to The government hasnt been The Maoists have two options: have fled their villages by the the Maoists has been the dramatic able to hide its delight. However, give up violence and join the hundredsA of thousands. The extradition by India of senior Maoist spokesman Kamal Thapa denied political mainstream, or antagonise countrys military budget has leaders Matrika Yadav and Suresh there would be any peace overtures India further, says Shyam increased at least three times more Ale this week. An Indian embassy to the Maoists as a result. We will Shrestha, editor of the leftist than peacetime levels. Most of the official confirmed the handover and carry on with our military operations, monthly magazine Mulyankan. -

Women in Nepal

COUNTRY BRIEFING PAPER WOMEN IN NEPAL Asian Development Bank Programs Department West Division 1 December 1999 iii This publication is one of a series prepared by consultants in conjunction with the Programs Department and Social Development Division (SOCD). The purpose of the series is to provide information on the status and role of women to assist ADB staff in formulating country operational strategies, programming work, and designing and implementing projects. The study has been produced by a team of ADB consultants, Meena Acharya, Padma Mathema, and Birbhadra Acharya, supported by field work consultant Saligram Sharma. Overall guidance and supervision of the study was provided by Yuriko Uehara (Director's Office, Programs Department [West]), and comments have been provided, at different stages, by Shireen Lateef and Manoshi Mitra (SOCD) in addition to related departments within ADB. Substantial editing and rewriting has been undertaken by Sonomi Tanaka (SOCD). Production assistance was provided by Ma. Victoria R. Guillermo (SOCD). The findings of the study were shared with some Kathmandu-based NGOs through a consultation workshop in August 1998. The views and interpretations in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Asian Development Bank. v Contents List of Abbreviations x Executive Summary xiii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Population and Geography 1 B. Human Development Indicators 2 C. Cultural Setting 3 D. The Economy 3 E. Political and Administrative Systems 4 CHAPTER 2. SOCIAL STATUS OF WOMEN 7 A. Patriarchy and Marriage 7 B. Fertility and Family Planning 9 C. Health and Nutrition 11 D. Education 14 1.