Writers and Readers in Transitional Nepal Michael Hutt (SOAS, London)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

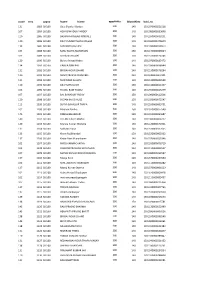

Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001

P|D|LL|S G8 G10 Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001 Maiwakhola Gaunpalika Patidanda Ma Vi 15 22 37 25 17 42 010360002 Meringden Gaunpalika Singha Devi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 8 2 10 0 0 0 010370001 Mikwakhola Gaunpalika Sanwa Ma V 27 26 53 50 19 69 010160009 Phaktanglung Rural Municipality Saraswati Chyaribook Ma V 28 10 38 33 22 55 010060001 Phungling Nagarpalika Siddhakali Ma V 11 14 25 23 8 31 010320004 Phungling Nagarpalika Bhanu Jana Ma V 88 77 165 120 130 250 010320012 Phungling Nagarpalika Birendra Ma V 19 18 37 18 30 48 010020003 Sidingba Gaunpalika Angepa Adharbhut Vidyalaya 5 6 11 0 0 0 030410009 Deumai Nagarpalika Janta Adharbhut Vidyalaya 19 13 32 0 0 0 030100003 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Janaki Ma V 13 5 18 23 9 32 030230002 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Singhadevi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 7 7 14 0 0 0 030230004 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Jalpa Ma V 17 25 42 25 23 48 030330008 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Khambang Ma V 5 4 9 1 2 3 030030001 Ilam Municipality Amar Secondary School 26 14 40 62 48 110 030030005 Ilam Municipality Barbote Basic School 9 9 18 0 0 0 030030011 Ilam Municipality Shree Saptamai Gurukul Sanskrit Vidyashram Secondary School 0 17 17 1 12 13 030130001 Ilam Municipality Purna Smarak Secondary School 16 15 31 22 20 42 030150001 Ilam Municipality Adarsha Secondary School 50 60 110 57 41 98 030460003 Ilam Municipality Bal Kanya Ma V 30 20 50 23 17 40 030460006 Ilam Municipality Maheshwor Adharbhut Vidyalaya 12 15 27 0 0 0 030070014 Mai Nagarpalika Kankai Ma V 50 44 94 99 67 166 030190004 Maijogmai Gaunpalika -

Women's Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation

Women’s Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation Emerging issues, adaptive practices, and priorities in Nepal ICIMOD Working Paper 2014/3 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. ICIMOD gratefully acknowledges the support of its core donors: The Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. 2 ICIMOD Working Paper 2014/3 Women’s Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation: Emerging issues, adaptive practices, and priorities in Nepal Dibya Devi Gurung, WOCAN Suman Bisht, ICIMOD International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, Nepal, August 2014 Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2014 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. -

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

S.No Pay Order No Beneficiary / Investor Name Amount Branch/Draft

List of Investors/Applicants for IPO Refund Amount sent to Investors Protection Fund updated as on 2077.03.31 B.S. S.no Pay Order No Beneficiary / Investor Name Amount Branch/Draft 1 6-A-459 Sneha Beriwal 7,000.00 Lazimpat 2 6-A-101 Sakuntala Hada 1,000.00 Lazimpat 3 6-A-102 Sonika Hada 1,000.00 Lazimpat 4 6-A-401 Laxman Kumar Jalan 4,000.00 Lazimpat 5 6-N-92 Gunkeshari Pradhan 1,000.00 Lazimpat 6 6-N-1061 Ramchandra Acharya 1,000.00 Lazimpat 7 6-N-1201 Ashwin Pandey 1,000.00 Lazimpat 8 31-N-73 Kaushalya Devi Sarada 10,000.00 Draft 9 31-N-107 Ramlal Chaudhary 1,000.00 Draft 10 31-N-109 Keshav Subedi 2,000.00 Draft 11 31-A-11 Chandrakala Devi Shah 1,000.00 Draft 12 4-N-4635 Sindhu Adhikari 1,000.00 Kathmandu 13 4-N-5092 Dibyashwori Shrestha 1,000.00 Kathmandu 14 4-N-5093 Mangala Shrestha 1,000.00 Kathmandu 15 4-N-5100 Ravi Shrestha 1,000.00 Kathmandu 16 4-N-5101 Diba Shrestha 1,000.00 Kathmandu 17 4-N-12743 Bidya Laxmi Shrestha 1,000.00 Kathmandu 18 4-N-12744 Ram Narayan Shrestha 1,000.00 Kathmandu 19 4-N-12745 Laxman Hari Shrestha 1,000.00 Kathmandu 20 4-N-12746 Kuber Narayan Shrestha 1,000.00 Kathmandu 21 4-N-13606 Durgadevi Regmi 1,000.00 Kathmandu 22 4-N-8857 Mamata Kumari Goyal 5,000.00 Kathmandu 23 4-N-8858 Harishchandra Goyal 5,000.00 Kathmandu 24 4-N-8859 Geeta Devi Goyal 5,000.00 Kathmandu 25 4-N-8860 Jyoti Kumari Goyal 5,000.00 Kathmandu 26 4-N-8861 Naresh Kumar Goyal 5,000.00 Kathmandu 27 4-N-8883 Tirtha Bahadur Lama 2,000.00 Kathmandu 28 4-N-9087 Sanjay Kumar K.C. -

Nepal: the Maoists’ Conflict and Impact on the Rights of the Child

Asian Centre for Human Rights C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi-110058, India Phone/Fax: +91-11-25620583; 25503624; Website: www.achrweb.org; Email: [email protected] Embargoed for: 20 May 2005 Nepal: The Maoists’ conflict and impact on the rights of the child An alternate report to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child on Nepal’s 2nd periodic report (CRC/CRC/C/65/Add.30) Geneva, Switzerland Nepal: The Maoists’ conflict and impact on the rights of the child 2 Contents I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 4 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS .................. 5 III. GENERAL PRINCIPLES .............................................................................. 15 ARTICLE 2: NON-DISCRIMINATION ......................................................................... 15 ARTICLE 6: THE RIGHT TO LIFE, SURVIVAL AND DEVELOPMENT .......................... 17 IV. CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS............................................................ 17 ARTICLE 7: NAME AND NATIONALITY ..................................................................... 17 Case 1: The denial of the right to citizenship to the Badi children. ......................... 18 Case 2: The denial of the right to nationality to Sikh people ................................... 18 Case 3: Deprivation of citizenship to Madhesi community ...................................... 18 Case 4: Deprivation of citizenship right to Raju Pariyar........................................ -

Samaj Laghubitta Bittiya Sanstha Ltd. Demat Shareholder List S.N

SAMAJ LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA SANSTHA LTD. DEMAT SHAREHOLDER LIST S.N. BOID Name Father Name Grandfather Name Total Kitta Signature 1 1301010000002317 SHYAM KRISHNA NAPIT BHUYU LAL NAPIT BHU LAL NAPIT / LAXMI SHAKYA NAPIT 10 2 1301010000004732 TIKA BAHADUR SANJEL LILA NATHA SANJEL DUKU PD SANJEL / BIMALA SANJEL 10 3 1301010000006058 BINDU POKHAREL WASTI MOHAN POKHAREL PURUSOTTAM POKHAREL/YADAB PRASAD WASTI 10 4 1301010000006818 REJIKA SHAKYA DAMODAR SHAKYA CHANDRA BAHADUR SHAKYA 10 5 1301010000006856 NIRMALA SHRESTHA KHADGA BAHADUR SHRESTHA LAL BAHADUR SHRESTHA 10 6 1301010000007300 SARSWATI SHRESTHA DHUNDI BHAKTA RAJLAWAT HARI PRASAD RAJLAWAT/SAROJ SHRESTHA 10 7 1301010000010476 GITA UPADHAYA SHOVA KANTA GNAWALI NANDA RAM GNAWALI 10 8 1301010000011636 SHUBHASINNI DONGOL SURYAMAN CHAKRADHAR SABIN DONGOL/RUDRAMAN CHAKRADHAR 10 9 1301010000011898 HARI PRASAD ADHIKARI JANAKI DATTA ADHIKARI SOBITA ADHIKARI/SHREELAL ADHIKARI 10 10 1301010000014850 BISHAL CHANDRA GAUTAM ISHWAR CHANDRA GAUTAM SAMJHANA GAUTAM/ GOVINDA CHANDRA GAUTAM 10 11 1301010000018120 KOPILA DHUNGANA GHIMIRE LILAM BAHADUR DHUNGANA BADRI KUMAR GHIMIRE/ JAGAT BAHADUR DHUNGANA10 12 1301010000019274 PUNESHWORI CHAU PRADHAN RAM KRISHNA CHAU PRADHAN JAYA JANMA NAKARMI 10 13 1301010000020431 SARASWATI THAPA CHITRA BAHADUR THAPA BIRKHA BAHADUR THAPA 10 14 1301010000022650 RAJMAN SHRESTHA LAXMI RAJ SHRESTHA RINA SHRESTHA/ DHARMA RAJ SHRESTHA 10 15 1301010000022967 USHA PANDEY BHAWANI PANDEY SHYAM PRASAD PANDEY 10 16 1301010000023956 JANUKA ADHIKARI DEVI PRASAD NEPAL SUDARSHANA ADHIKARI -

I. Introduction Writer Parijat, the Nepali Name for a Species of Jasmine With

I. Introduction Writer Parijat, the Nepali name for a species of jasmine with a special religious significance, is the pen name adopted by Bishnu Kumari Waiba, a Tamang woman who was born in the Tea-Estate of Darjeeling in 1937 A.D. She was the daughter of Kalu Sing Waiba and Amrita Moktan. She has been hailed by her contemporaries as one of the most innovative and first modern novelist of Nepal. The themes and philosophical outlook of her poems, novels and stories are influenced by her Marxist and feminist views and her own personal circumstances. Parijat suffered from a partial paralysis since her youth and ventured from her home only rarely during the past twenty years. She was unmarried and childless, a status that was not usual for a woman in Nepalese society and that is due partly to her illness and partly, it seems due to personal preference. Despite her disability, Parijat is a formidable force in Nepali literature, and her flower-filled room in a house near Balaju has become a kind of shrine for progressive Nepali writers. Parijat is a beautiful, intense-looking woman. She is concerned with a Nepali tribal group of antiquity but of uncertain origin. She is a Buddhist by birth and her childhood was deeply unhappy. According to Lama Religion, she was named Chheku Lama. Her mother died while Parijat was still young, and an elder brother drowned shortly afterward. At the age of about thirteen, it seems that she became passionately involved in a love affair that ended in heartbreak and a period of intense depression. -

POST-MORTEM Round, and the Outcome Will Be Decided at the Party’S Upcoming Convention in Pokhara

#24 5 - 11 January 2001 20 pages Rs 20 EXCLUSIVE 69-41 The ruling party’s vicious internal power struggle is now in its final POST-MORTEM round, and the outcome will be decided at the party’s upcoming convention in Pokhara. But before In the 36 hours of mobocracy that ruled that, there was the small matter of Kathmandus streets last week, we caught the no-trust vote against Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala that a glimpse of an area of darkness in our wannabe Sher Bahadur Deuba countrys soul. wanted to settle first. The vote was set for 28 December, and both BINOD BHATTARAI factions did some grandstanding ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ University. The government was not there at about secret or open ballot to hide n 26-27 December, Nepal had no a critical moment. It was only on Wednesday the fact that they were both terrified government. Legitimate political parties afternoon, after things began to get really out o of control that the Prime Ministers office of losing. cowered, citizens were afraid to speak Both sides met for the duel in out, the capital sank into an anarchic limbo. It began taking stock. The only party that the murky fog-shrouded Singha was all the more shocking because we had showed some sanity was the main opposition Durbar on Thursday morning. The been brought up to believe that things like this UML, which began drafting its now-famous rebels led by Deuba boycotted the werent supposed to happen in peaceful Nepal. statement warning people not to fish in vote when the Koirala camp It wont be the same again: Nepalis of all muddy waters. -

![By Madhav Prasad Ghimire [Kinnar Kinnari] by Madhav Prasad Ghimire](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7193/by-madhav-prasad-ghimire-kinnar-kinnari-by-madhav-prasad-ghimire-1867193.webp)

By Madhav Prasad Ghimire [Kinnar Kinnari] by Madhav Prasad Ghimire

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} [Kinnar Kinnari] by Madhav Prasad Ghimire [Kinnar Kinnari] by Madhav Prasad Ghimire. Nepali Literature g]kfnL ;flxTo. History. Interview. Photo Gallery. Rachana. Your Articles. Suggestions. Index. N epali Language has been evolved from Sanskrit . Initially Nepali was considered as "Gorkhali" or "Khas" language . It got its name 'Nepali' only after king Prithivi Narayan Shah united the country . The oldest evidence found in Nepali Language is Ashok Chilla's bronze plate, carved in 1321 B.S. The oldest book found is 'Khanda Khadya' (1642) whose writer is still unknown. Another old books without author's name are 'swasthani Bharatkatha'.(1658) and 'Baj Parikxya' (1700).The oldest book whose author is known is translated version of Bani Bilas Jyotirbid's 'Jwarup Pati Chikitsha'(1773) and 'Prayashit Predip' by Prem Nidhi Pant in Sanskrit.Both the books were tranlated by Prem Nidhi Pant . According to Dr. T.N. Sharma, to make the study of the history of Nepali Literature convinient NL can be divided in to 5 eras. I.Pre Bhanu Bhakta Era (from beginning to 1871 B.S.) II. Bhanu Bhakta Era (from 1872 B.S. to 1936 B.S.) III. Moti Ram Era (from 1940B.S. to 1976 B.S.) IV. Pre Revolution Era (from 1977 B.S. to 2007 B.S.) V. Post Revolution Era (from 2007 B.S. to present.) I. Pre Bhanu Bhakta Era ( beginning to 1871B.S.) In that era the articles were generally written upon the bravery. In any language, the literature written in primitive age are mostly found as poetry. But, without the proper development of the prose poetry cannot be written. -

Ccode Srno Appno Fname Lname Appshkitta Allotedkitta Boid No 131

ccode srno appno fname lname appshkitta AllotedKitta boid_no 131 1083 SJCL00 Girja Shankar Baniya 300 140 1301070000221518 107 1084 SJCL00 HOM BAHADUR PANDEY 300 140 1301080000289648 120 1085 SJCL00 BASANTA PRASAD POKHREL 300 140 1301260000030231 120 1086 SJCL00 DILIP KUMAR THAPA MAGAR 300 140 1301060001275649 139 1087 SJCL00 SANTOSH GAUTAM 300 140 1301390000164973 104 1088 SJCL00 SANU MAIYA MAHARJAN 300 150 1301170000039604 102 1089 SJCL00 Rambabu Poudel 300 150 1301370000124146 120 1090 SJCL00 Bishnu Prasad Yadav 300 140 1301070000185472 134 1091 SJCL00 GANGA RAM PAL 300 140 1301280000038944 131 1092 SJCL00 BIR BAHADUR CHAND 300 140 1301130000178294 120 1093 SJCL00 SHIVA PRASAD POKHAREL 300 140 1301240000000151 131 1094 SJCL00 SURENDRA SAHANI 300 140 1301130000044538 120 1095 SJCL00 DILIP MANI DIXIT 300 150 1301130000011337 102 1096 SJCL00 THAGU RAM THARU 300 140 1301550000015279 107 1097 SJCL00 BAL BAHADUR YADAV 300 150 1301080000122596 120 1098 SJCL00 SUDAN RAJ CHALISE 300 150 1301020000072547 113 1099 SJCL00 SURYA BAHADUR THAPA 300 140 1301100000099791 102 1100 SJCL00 Madhav Pantha 300 150 1301070000077540 143 1101 SJCL00 DINESH BHANDARI 300 150 1301010000054687 140 1102 SJCL00 UTTAM SINGH MAHAT 300 140 1301380000004252 120 1103 SJCL00 Krishna Kumar Shrestha 300 150 1301120000171901 137 1104 SJCL00 Sadhana Hada 300 140 1301370000317605 133 1105 SJCL00 Khem Raj Bhandari 300 150 1301320000060332 137 1106 SJCL00 Kedar Man Munankarmi 300 140 1301370000325346 102 1107 SJCL00 NIROJ KARMACHARYA 300 140 1301100000076719 102 1108 SJCL00 UDDHAB -

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation Volume 1,September2017 Volume cg'jfbs ;dfh g]kfn Society of Translators Nepal Nepalese Translation Volume 1 September 2017 Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Office bearers for 2016-2018 President Victor Pradhan Vice-president Bal Ram Adhikari General Secretary Bhim Narayan Regmi Secretary Prem Prasad Poudel Treasurer Karuna Nepal Member Shekhar Kharel Member Richa Sharma Member Bimal Khanal Member Sakun Kumar Joshi Immediate Past President Basanta Thapa Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Nepalese Translation is a journal published by Society of Translators Nepal (STN). STN publishes peer reviewed articles related to the scientific study on translation, especially from Nepal. The views expressed therein are not necessarily shared by the committee on publications. Published by: Society of Translators Nepal Kamalpokhari, Kathmandu Nepal Copies: 300 © Society of Translators Nepal ISSN: 2594-3200 Price: NC 250/- (Nepal) US$ 5/- EDITORIAL strategies the practitioners have followed to Translation is an everyday phenomenon in the overcome them. The authors are on the way to multilingual land of Nepal, where as many as 123 theorizing the practice. Nepali translation is languages are found to be in use. It is through desperately waiting for such articles so that translation, in its multifarious guises, that people diverse translation experiences can be adequately speaking different languages and their literatures theorized. The survey-based articles present a are connected. Historically, translation in general bird's eye view of translation tradition in the is as old as the Nepali language itself and older languages such as Nepali and Tamang. than its literature.