New Rice Varieties for Nepal Rainfed Agriculture Impact Assessment Study No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Napi Book Inside.Indd

Nepalese Journal on Geoinformatics Number : 11 Jestha 2069 BS May/June 2012 AD Annual publication of Survey Department, Government of Nepal The Content and the ideas of the article are solely of authors. Published by: Government of Nepal Ministry of Land Reform and Management Survey Department Min Bhavan, Kathmandu Nepal No. of copies : 500 © Copyright reserved by Survey Department Nepalese Journal Features Contents on Articles 1 AProspectofDigitalAirbornePhotogrammetry Approach for Cadastral Mapping in Nepal By Rabindra Man Tamrakar GEOINFORMATICS Page 1 Jestha 2069, May-June 2012 2 Detection of Building in Airborne Laser Number 11 Scanner Data and Aerial Images By Dilli Raj Bhandari Page 7 3 Evolution of Land Use Policy in Nepal Product Price By Rabin K. Sharma Maps Page 16 Page 30 4 LIS Activities in Nepal : Publica! ons An Overview in prospect of DoLIA Page 29 By Ram Kumar Sapkota Page 23 Control Points Page 30 5 Role of Survey Department In Disaster Management In Nepal Aerial Photographs and Map By Suresh Man Shrestha Transparencies Page 31 Page 49 Digital Data Layers 6 Transliteration System For Nepali Language Page 49 By Suresh Man Shrestha Page 37 Soter Data Page 49 Digital Orthophoto Image Data Page 49 News Looking back 2011 - 2012 Page 14 Obituary Page 29 Cover Page PG2 Stereoplo! er and Digital Photogrammetric Work Sta" on to Produce Topographic Maps Contents Review The First High Level Forum on Global Geospatial Information Management (GGIM), a United Nations Initiative Page 43 Professional Organiza" on Nepal Remote Sensing and Photogrammetric Society Page Page 46 Nepal GIS Society Page 47 Nepal Surveyors’ Association (NESA) Page 48 Regular Column Editorial Page II Forewords Page III Informa" ons Instruction and Guidelines for Authors Regarding Manuscript Preparation Page 42 Call for Papers Page 29 Participation in International Events Page 22 Calendar of International Events Page 36 Advisory Council Krishna Raj B.C. -

Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001

P|D|LL|S G8 G10 Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001 Maiwakhola Gaunpalika Patidanda Ma Vi 15 22 37 25 17 42 010360002 Meringden Gaunpalika Singha Devi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 8 2 10 0 0 0 010370001 Mikwakhola Gaunpalika Sanwa Ma V 27 26 53 50 19 69 010160009 Phaktanglung Rural Municipality Saraswati Chyaribook Ma V 28 10 38 33 22 55 010060001 Phungling Nagarpalika Siddhakali Ma V 11 14 25 23 8 31 010320004 Phungling Nagarpalika Bhanu Jana Ma V 88 77 165 120 130 250 010320012 Phungling Nagarpalika Birendra Ma V 19 18 37 18 30 48 010020003 Sidingba Gaunpalika Angepa Adharbhut Vidyalaya 5 6 11 0 0 0 030410009 Deumai Nagarpalika Janta Adharbhut Vidyalaya 19 13 32 0 0 0 030100003 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Janaki Ma V 13 5 18 23 9 32 030230002 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Singhadevi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 7 7 14 0 0 0 030230004 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Jalpa Ma V 17 25 42 25 23 48 030330008 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Khambang Ma V 5 4 9 1 2 3 030030001 Ilam Municipality Amar Secondary School 26 14 40 62 48 110 030030005 Ilam Municipality Barbote Basic School 9 9 18 0 0 0 030030011 Ilam Municipality Shree Saptamai Gurukul Sanskrit Vidyashram Secondary School 0 17 17 1 12 13 030130001 Ilam Municipality Purna Smarak Secondary School 16 15 31 22 20 42 030150001 Ilam Municipality Adarsha Secondary School 50 60 110 57 41 98 030460003 Ilam Municipality Bal Kanya Ma V 30 20 50 23 17 40 030460006 Ilam Municipality Maheshwor Adharbhut Vidyalaya 12 15 27 0 0 0 030070014 Mai Nagarpalika Kankai Ma V 50 44 94 99 67 166 030190004 Maijogmai Gaunpalika -

Women's Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation

Women’s Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation Emerging issues, adaptive practices, and priorities in Nepal ICIMOD Working Paper 2014/3 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. ICIMOD gratefully acknowledges the support of its core donors: The Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. 2 ICIMOD Working Paper 2014/3 Women’s Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation: Emerging issues, adaptive practices, and priorities in Nepal Dibya Devi Gurung, WOCAN Suman Bisht, ICIMOD International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, Nepal, August 2014 Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2014 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. -

Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne Mclean Charles Sturt University (Australia)

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 19 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin; Special Article 8 Topic: The Tharu 1999 Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne McLean Charles Sturt University (Australia) Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation McLean, Joanne (1999) "Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal," HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 19 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol19/iss2/8 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conservation and the linpact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne McLean Charles Sturt University (Australia) Since the establishment of the first national park in the United States in the nineteenth century, indig enous peoples have been forced to move from regions designated as parks. Some of these people have been relocated to other areas by the government, more often they have been told to leave the area and are given no alternatives (Clay, 1985:2). Introduction (Guneratne 1994; Skar 1999). The Thant are often de scribed as one people. However, many subgroups exist: The relocation of indigenous people from national Kochjla Tharu in the eastern Tarai, Chitwaniya and Desauri parks has become standard practice in developing coun in the central Tarai, and Kathariya, Dangaura and Rana tries with little regard for the impacts it imposes on a Tharu in the western Tarai (Meyer & Deuel, 1999). -

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

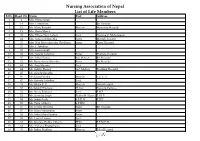

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Strengthening Livelihood Capacities to Disaster Risk Reduction - Compilation of Change Studies, Kathmandu, Nepal, Practical Action

S T R E N G T H E N I N G L I V E L I H O O D C A P A C I T I E S T O D I S A S T E R R I S K R E D U C T I O N I N N E P A L Compilation of Change Studies Study Team Dinanath Bhandari and Yuwan Malakar Suported By Ghanashyam Bhandari, SAHAMATI Yani Gaha, SAHAMATI Yadu Kandel, SAHAMATI Anil Prajapati, SAHAMATI Anju Adhikari, MADE Nepal Gita Kumal, MADE Nepal Baburam KC, MADE Nepal Reviewers Pieter van Den Ende, Practical Action Gehendra Gurung, Practical Action © Practical Action Nepal Office, 2011 In collaboration with SAHAMATI and MADE Nepal Citation: Practical Action (2011) Strengthening Livelihood Capacities to Disaster Risk Reduction - Compilation of Change Studies, Kathmandu, Nepal, Practical Action ISBN: 978-9937-8135-8-7 No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purpose without prior permission of the copyright holder. 'This material has been funded by UKaid from the Department for International Development, however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the department's official policies.' C O N T E N T S Foreword ii Why work in disaster risk reduction? iv Acronyms vi Chapter 1. Introduction 1 Chapter 2. Irrigation facilites reduce sensitivity to drought 10 Chapter 3. Electric fencing decreases exposure to wild animals 22 Chapter 4. Vegetables are an additional source of income to improve resilience 29 Chapter 5. Improved bee keeping and its contribution to reducing landslides 36 Chapter 6. -

Page Situation Report 2: Nepal Flood – Saptari District (18July 2019)

Situation Report 2: Nepal Flood – Saptari District (18 July 2019) Assessment conducted jointly by DCA and Koshi Victim Society (KVS). Data gathered from 11 July 2019 with assessment completed on 16, 17 and 18 July 2019. This report is produced by DCA Nepal, based on field assessment of affected municipalities, and additional meetings held with humanitarian agencies, local NGOs, and government officials. Summary » Floods caused by heavy rainfall in Nepal have been resulting in 90 dead, 29 missing, and 41 injured (Ministry of Home Affairs, 18 July). Properties, rice crops and livelihoods have also been lost. » Flood water has inundated thousands of houses along the high raised road and embankment areas, leaving at least 11,839 households temporarily displaced (UN Sit Rep – July 18, 2019). » The District Disaster Management Committee (DDMC) report shows that 13 of 18 municipalities in Saptari district are affected by floods and water logging, of which five are rural municipalities. » According to the Nepal Red Cross Society (NRCS), Saptari district is assessed to be one of the most hard- hit areas. No fatalities have been recorded yet. » DCA as a District Lead Support Agency (DLSA) of Saptari district, is supporting in enhancing coordination among aid agencies and government bodies as well as facilitating information sharing about flood adversities. 1 | P a g e Situation Overview On 17 July, the District Disaster Management Committee (DDMC), Saptari reported that 4,500 houses were affected by floodwater. Of these, 1,500 houses are severely damaged. DDMC has recommended that relief agencies go directly to the affected municipalities and coordinate with Local Government for relief distribution. -

Narayani Distric:- Bara Student's S.N

JANKALYAN PRATISTHAN (EKAL VIDHYALAY YOJANA) ANCHAL: -NARAYANI DISTRIC:- BARA STUDENT'S S.N. C0DE SANCH V.D.C. ACHARYA NAME Total Boys Girls 1 NPM05230101 SAHAJANATH Bhodaha-3 Nila Devi Misra 19 21 40 2 NPM05230102 SAHAJANATH Bhodaha-4 Ram Ayodhya Misra 16 11 27 3 NPM05230103 SAHAJANATH Dohari-3 Santosh Paswan 19 14 33 4 NPM05230104 SAHAJANATH Haraiya-5 Lalbabu Sash 13 15 28 5 NPM05230105 SAHAJANATH Haraiya-7 Mira Kumari Sash 16 19 35 6 NPM05230106 SAHAJANATH karaiya-1 Ramanand Chaudhari 16 11 27 7 NPM05230107 SAHAJANATH Karaiya-7 Ram Asish Thakur 12 16 28 8 NPM05230108 SAHAJANATH Manaharwa-7 Sita Aryal 14 16 30 9 NPM05230109 SAHAJANATH Prastoka-9 Ghansayam Nepal 17 13 30 10 NPM05230110 SAHAJANATH Prastoka-3 Atmaram Shah 22 18 40 11 NPM05230111 SAHAJANATH Prastoka-3 Upendar Mandal 19 17 36 12 NPM05230112 SAHAJANATH Tetariya-9 Krishan Chaudhari 20 16 36 13 NPM05230113 SAHAJANATH Utrajhitkaika-8 Raju Paswan 13 12 25 14 NPM05230114 SAHAJANATH Pipara-2 Ritu Devi Chaudhary 14 18 32 15 NPM05230115 SAHAJANATH Bhodaha-4 Anuradha Kumari Sash 17 15 32 16 NPM05230201 GADHI MAI Amarpati-3 Pratima Devi Chaudhari 11 14 25 17 NPM05230202 GADHI MAI Bisunpurawa-1 Gita Kumari Chaudhary 17 19 36 18 NPM05230203 GADHI MAI Bisunpurawa-8 Urmila Devi Chaudhari 14 13 27 19 NPM05230204 GADHI MAI Gadahal-2 Sarda Devi Chaudhari 17 14 31 20 NPM05230205 GADHI MAI Gadahal-9 Sunita Misra 11 15 26 21 NPM05230206 GADHI MAI Kakadi-8 Ranju Devi Chaudhari 16 19 35 22 NPM05230208 GADHI MAI Pipra-1 Ganita Chaudhary 16 15 31 23 NPM05230209 GADHI MAI Sihorwa-2 Shyam Chaudhari 16 15 31 24 NPM05230210 GADHI MAI Sihorwa-4 Ashika Kumar Chaudhari 15 14 29 25 NPM05230211 GADHI MAI Tetariya Amit Kuamar Gupta 18 12 30 26 NPM05230212 GADHI MAI Tetariya-2 Ritu Kumary Chaudhary 16 14 30 27 NPM05230213 GADHI MAI Umjan-3 Bindu Devi Chaudhari 16 15 31 28 NPM05230214 GADHI MAI Umjan-3 Sunita Devi Chaudhari 13 15 28 29 NPM05230215 GADHI MAI Khopawa-4 Anita Devi Chaudhari 17 14 31 460 440 900 DISTRIC - CHITWAN STUDENT'S S.N. -

Manual for Community-Based Flood Management Nepal

MANUAL FOR COMMUNITY-BASED FLOOD MANAGEMENT NEPAL Asia Pacific J. Env. Dev., 11(1&2), 2004, pp. 227-304 MANUAL FOR COMMUNITY-BASED FLOOD MANAGEMENT IN NEPAL Table of Contents List of Acronyms 230 Executive Summary 231 1 Introduction 236 2 Classification of Floods and Flood Prone Areas 241 3 Pre-Flood Preparedness 244 4 During Flood Responses 255 5 Post-Flood Rehabilitation and Maintenance 256 6 Managing Information for Future References 258 Annexures 260 List of Acronyms ADB/N : Agricultural Development Bank of Nepal CBOs : Community Based Organization CFMC : Community Flood Management Committee DADO : District Agriculture Development Office DDC : District Development Committee DHM : Department of Hydrology and Meteorology DNCRC : District Natural Calamity Relief Committee DOR : Department of Roads DWIDP : Department of Water Induced Disaster Prevention DWRC : District Water Resources Committee GLOF : Glacier Lake Outburst Flood INGO : International Non-Governmental Organization JICA : Japan International Cooperation Agency NGO : Non-Governmental Organizations NRCS : Nepal Red Cross Society RCC : Reinforced Cement Concrete RUAA Roorkee University Alumni Association SIREN Society of Irrigation Engineers UNDP : United Nations Development Programme VDC : Village Development Committee EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Floods in Nepal Unstable steep slopes, weak and fragile geological formation of young mountains along with heavy monsoon rainfall make Nepal one of the most hazardous areas in the world. Because of its topographical variation and geological characteristics together with torrential rain during the monsoon season, the country frequently suffers from different kinds of water induced disasters like soil erosion, landslide, debris flow, floods etc. These phenomena cause loss of lives and property and pose severe hazards to physical infrastructures resulting in the disruption of the social and economic development of the country. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Nepal

Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Nepal Forests for Prosperity Project Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) March 8, 2020 Executive Summary 1. This Environment and Social Management Framework (ESMF) has been prepared for the Forests for Prosperity (FFP) Project. The Project is implemented by the Ministry of Forest and Environment and funded by the World Bank as part of the Nepal’s Forest Investment Plan under the Forest Investment Program. The purpose of the Environmental and Social Management Framework is to provide guidance and procedures for screening and identification of expected environmental and social risks and impacts, developing management and monitoring plans to address the risks and to formulate institutional arrangements for managing these environmental and social risks under the project. 2. The Project Development Objective (PDO) is to improve sustainable forest management1; increase benefits from forests and contribute to net Greenhouse Gas Emission (GHG) reductions in selected municipalities in provinces 2 and 5 in Nepal. The short-to medium-term outcomes are expected to increase overall forest productivity and the forest sector’s contribution to Nepal’s economic growth and sustainable development including improved incomes and job creation in rural areas and lead to reduced Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions and increased climate resilience. This will directly benefit the communities, including women and disadvantaged groups participating in Community Based Forest Management (CBFM) as well and small and medium sized entrepreneurs (and their employees) involved in forest product harvesting, sale, transport and processing. Indirect benefits are improved forest cover, environmental services and carbon capture and storage 3. The FFP Project will increase the forest area under sustainable, community-based and productive forest management and under private smallholder plantations (mainly in the Terai), resulting in increased production of wood and non-wood forest products.